Care of Patients with Immune and Lymphatic Disorders

Objectives

1. Summarize the ideal actions of therapeutic immunosuppressive drugs.

2. Explain the importance of minimizing the administration of antimicrobial agents.

3. Describe effects of aging on the immune system.

4. Explain why an immune-suppressed patient, with infection, may not have an elevated body temperature.

5. Explain how an allergic reaction occurs during an excessive immune response.

6. Summarize the nurse’s role in helping the patient to control allergies.

9. Compare and contrast the two types of lymphoma and how they are diagnosed.

1. List nursing measures for the prevention of infection for an immunocompromised patient.

2. List key elements for data collection, if an immune-suppressant disorder is suspected.

3. Perform nursing assessment on a patient with a primary allergic condition.

5. Perform nursing interventions for a patient with lymphedema.

6. Review a nursing care plan for a patient who has systemic lupus erythematosus.

7. List interventions that can be used for a patient with fibromyalgia.

Key Terms

allergy (p. 236)

allodynia (p. 254)

anaphylaxis (ă-nă-fă-LĂK-sĭs, p. 236)

angioedema (ăn-jē-ōh-ĕ-DĒ-mă, p. 241)

atopy (ĂT-ōh-pē, p. 237)

erythema (p. 245)

histamine (p. 236)

hyperalgesia (p. 254)

hypersensitivity reactions (p. 236)

iatrogenic (p. 234)

immunosuppression (p. 234)

lymphadenopathy (p. 250)

lymphedema (p. 253)

patch test (p. 237)

relapse (p. 250)

remissions (p. 254)

scratch test (p. 237)

syndrome (p. 243)

urticaria (ŭr-tĭ-KĀ-rē-ăh, p. 241)

wheals (wēlz, p. 241)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Immune Disorders

Abnormal responses of the immune system are divided into two basic categories: immune deficiency disorders and autoimmune diseases. In immune deficiency disorders there is an insufficient production of antibodies, immune cells, or both and the disorders may be congenital or acquired. A deficiency in the immune system leaves the body unable to resist foreign microbes or toxins. Autoimmune disorders involve the overreaction or hypersensitivity to antigens from the external environment where the immune system is unable to tell the difference between “non-self” (foreign cells) and “self” (the body’s own cells).

Common viral infections, such as influenza or infectious mononucleosis, can cause a short-term depression of an effective immune response. Other conditions that decrease the immune system include smoking, malnutrition, surgery, and stress. The immune system can also be therapeutically suppressed; for example, antirejection medications prevent a tissue transplant rejection.

Therapeutic immunosuppression

A variety of disorders or conditions can be treated or controlled by medications or therapies such as corticosteroids, hemodialysis, organ transplantation, or radiation. However, some of these treatments can lead to chronic medical conditions or iatrogenic complications such as diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, chronic infections, and significant weight gain. Drug-induced immunosuppression, often referred to as therapeutically induced immunosuppression, requires a delicate balance between the control of the body’s immune response and the side effects. The ideal balance of therapeutic immunosuppressive drugs would inhibit the normal immune system response; defend against invasion from assorted microbial agents; and control the occurrence of the usual side effects, such as stomach ulcers and tremors (Box 12-1).

An example of an iatrogenic (a side effect of medical treatment) immune suppression occurs with an organ transplant recipient. This type of patient is at increased risk of organ rejection if the patient’s own immune system is activated to destroy this “foreign” organ. The patient must take multiple medications, as a lifetime therapy, such as azathioprine (Imuran) and cyclosporine (Sandimmune) (Table 12-1).

Table 12-1

Types of Antirejection Medications

| Name | Action |

| Antithymocyte globulin | Immunosuppressive agent that selectively destroys T lymphocytes. |

| Basiliximab | Binds and blocks T cells from replicating and from activating B cells, thereby decreasing the production of antibodies that can lead to rejection. |

| Daclizumab | Inhibits the function of interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptors on the T cells, which prevents the cells from activating and stimulating the formation of antibodies. |

| Lymphocyte immune globulin | Reduces the number of circulating thymus-dependent lymphocytes in the blood. |

| Methylprednisolone | A corticosteroid with anti-inflammatory properties. |

| Muromonab-CD3 | Blocks the function of CD3 molecules in the membrane of human T cells. |

| Rapamycin | An antimicrobial that demonstrates antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and immunosuppressive properties, which inhibits IL-2 so the T and B cells are not activated. |

There is significant evidence that use of antirejection medications increases the survival rate of patients with certain organ transplants, but it does not completely eliminate the danger of organ rejection or other health complications.  Immunosuppressant drugs may need to be adjusted according to the systemic and immune response of each patient and to prevent toxicity.

Immunosuppressant drugs may need to be adjusted according to the systemic and immune response of each patient and to prevent toxicity.

Immunosuppressive agents are used to manage autoimmune disorders such as multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, rheumatoid arthritis, and select neoplastic growths.

Diagnostic Tests and Treatment of Immune Deficiencies

In the early stages of an autoimmune disorder, definitive diagnosis may be difficult. The health care provider must look at the complete health history, current complaints or symptoms, and physical examination findings so that the appropriate diagnostic studies can be performed (Box 12-2).

Some patients’ immune systems have virtually no ability to respond to antigens (requires lymphocytes that are sensitized) or to synthesize antibodies, whereas others have a temporary minor defect in the humoral or cell-mediated immune response. In some types of immune deficiency, passive immunity can be accomplished by transfusing specifically sensitized lymphocytes to help the patient resist infection. Injections of immune globulin may be given on a regular basis to provide passive immunity for those who are unable to produce their own antibodies. When impaired function of the bone marrow is involved, as in leukemia, the patient may receive a bone marrow transplant to provide the stem cells that will eventually become immune bodies. To help prevent or combat infection in immunosuppressed patients, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor—filgrastim (Neupogen)—can be used to promote the growth of neutrophils, especially in patients with AIDS or in certain types of cancer that produce significant immunodeficiency.

As soon as an infection is evident, antimicrobial agents are usually given. However, these drugs can also be immunosuppressive. One of the National Patient Safety Goals is to decrease the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, which can lead to the development of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) leaving the patient more vulnerable to infection and other complications.

Ideally, treatment in an immunocompromised patient is aimed at controlling the disease or eliminating the condition that led to an inadequately functioning immune system. For example, with nephrosis, liver disease, drug toxicity, and viral infections, this may be possible. In other instances, treatment consists of minimizing the effects of the immune deficiency. Development of immune-specific drugs used in the treatment of HIV/AIDS has assisted in finding effective treatments in some other types of immunodeficiency disorders.

Nursing management

Assessment (Data Collection)

When an immune deficiency is suspected, information is gathered about the current physical status of the patient, such as her general state of health, infections she may have recently had, how the infections affected her, and how frequently they occur. It is also important to assess for risk behaviors such as intravenous drug use, multiple sexual partners, exposure to HIV, immunosuppressive drug therapy, alcohol consumption, and family history of genetic immune disorders. Assess for occupational or environmental exposure to assorted agents. Nutritional status should be assessed by measuring height and weight and inspecting the skin, hair, and overall appearance. If a significant decrease in weight is noted (usually greater than 10%), ask if it was intentional. If not, ask when the loss first started.

Physical assessment should include palpation of the superficial lymph nodes in the neck, axilla, and groin to detect any abnormalities, as well as assessing the body systems involved in the patient’s chief complaints. For example, the patient tells the nurse that she feels a bulge around her stomach, so the nurse would palpate both upper quadrants of the abdomen.

Body temperature should be closely monitored for significant changes, although immune-deficient patients may not have a temperature elevation even in the presence of infection. The body may not be able to recognize that an infection is beginning until much later in the process because of the body’s impaired immune response. Therefore the nurse must assess the whole patient and not just one or two areas, because important signs or symptoms of potential complications can be missed if not performed correctly.

Nursing Diagnosis and Planning

Nursing diagnoses for patients with immune deficiency should always include Risk for infection. The primary nursing goals when caring for a patient who has an immune deficiency are to (1) protect the patient from infection, (2) improve her health status, and (3) promote as high a degree of wellness as possible. Expected outcomes based on the nursing diagnoses might include:

Planning care for the patient with an immune deficiency focuses on preventing exposure to pathogens. A patient whose immune deficiency is severe will likely need to be placed in transmission-based isolation precautions (formerly called reverse isolation or Neutropenic Precautions). (See Chapter 17 for additional information on neutropenia.) Working with patients in this type of isolation requires more time because of the need for donning and removing the personal protective equipment (PPE) before entering and on leaving the patient’s room (see Chapter 6). Integrating care of this patient along with the rest of the patient assignments for the shift needs to be carefully planned.

Implementation

Proteins are needed to synthesize antibodies. If the patient has a condition or is on medications that suppress appetite or cause nausea, nutritional intake can be inadequate. Nutritional supplements may be added, and multiple small meals of high-protein foods chosen by the patient may need to be scheduled throughout the day. However, if the patient is on corticosteroid therapy, appetite control may be a challenge and the patient must be carefully monitored for weight gain. Providing low-calorie snacks such as vegetables and certain fruits to eat instead of high-calorie chips, cookies, and sodas would be helpful.

Excessive stress can further depress immune function. Many factors related to family, employment, finances, or transportation can significantly increase the stress level for the patient or loved ones. As illness progresses, many patients may have difficulties at school or work. Collaboration with a social worker is often indicated. Referrals to community resources can greatly assist the patient and family in dealing with the added stress. The nurse can also be instrumental in teaching the patient stress-reduction strategies, such as light exercise, meditation, relaxation techniques, and guided imagery (see Chapter 7 ).

).

Provide patient education regarding the immune disorder and any therapy that the patient is to receive. Teach the patient and family to assess for signs of infection and to report them immediately (see Chapter 11).

Evaluation

Ensure that strict hand hygiene is being performed and adhere to transmission-based isolation precautions. Check laboratory test results to assess whether immune function is improving. B-cell and T-cell assays are particularly important. Evaluate the patient for evidence of recovery from any infection that might have been present, as well as for general well-being, appetite, weight changes, and for side effects of medications or other therapies.

Disorders of inappropriate immune response

Allergy and Hypersensitivity

An allergy is an abnormal response to certain substances; it is considered to be a systemic immune disorder, rather than a localized one; and the reaction can be seen or expressed in multiple body systems. Hypersensitivity reactions, better known as allergic reactions, are the body’s excessive response to a normally harmless substance. The severity of the condition can range from a mild rash to anaphylaxis (an extreme allergic reaction that is life threatening).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

As the environment has become cleaner over the past decades, there has been an increase in the development of allergies, especially among those in a higher socioeconomic status, living in an urban area versus rural, and being the first-born child (less exposure to other illnesses from siblings). There also appears to be a strong hereditary component to hypersensitive allergic reactions as well (Grammatikos, 2008).

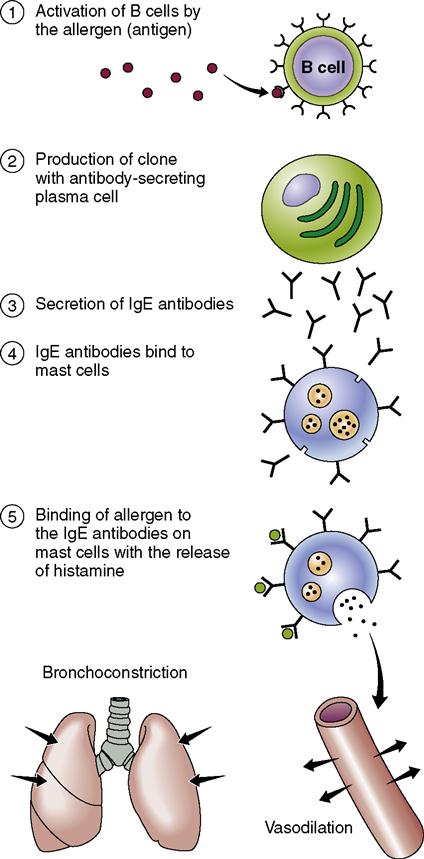

Allergies are divided into two major categories: (1) immediate hypersensitivity reactions that are mast cell mediated (type I hypersensitivity) and (2) delayed-reaction allergies involving T cells (type II hypersensitivity). As with all types of normal and abnormal immune response, a reaction will not occur until an individual’s body cells have been sensitized to the specific substance that triggers the response. This means that on first contact with the allergen, the body’s immune system is triggered to produce immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to recognize the specific antigen. On the second and subsequent contacts with the allergen, the antibodies specific to the allergen are rapidly produced and released into the circulating blood or in the lymphoid tissues, in larger and larger quantities. Because of the increased amount of antibodies, they can be quickly transported to the location of the allergen, causing a more rapid, and sometimes virulent, allergic reaction.  Type I or rapid inflammatory reactions result from the increased production of mast cells and basophils from IgE antibodies. During this reaction, histamine is released from a mast cell mediator. When histamine is released because of an immune response, it triggers increased mucus secretions, vasodilation, and increased vascular permeability, which leads to tissue edema. Dilated blood vessels transport the IgE antibodies, histamine, and other chemicals to the site of exposure to the allergen (Figure 12-1).

Type I or rapid inflammatory reactions result from the increased production of mast cells and basophils from IgE antibodies. During this reaction, histamine is released from a mast cell mediator. When histamine is released because of an immune response, it triggers increased mucus secretions, vasodilation, and increased vascular permeability, which leads to tissue edema. Dilated blood vessels transport the IgE antibodies, histamine, and other chemicals to the site of exposure to the allergen (Figure 12-1).

If the mast cells are IgE dependent, they typically produce only a localized allergic response. Examples of this are allergic conjunctivitis or allergy-induced asthma. A person who has atopy (a response that affects various parts of the body without being in direct contact with the allergen), such as seen in eczema, tends to be hypersensitive to a variety of allergens. Type II or delayed reactions result from increased production of IgG.

Signs and Symptoms

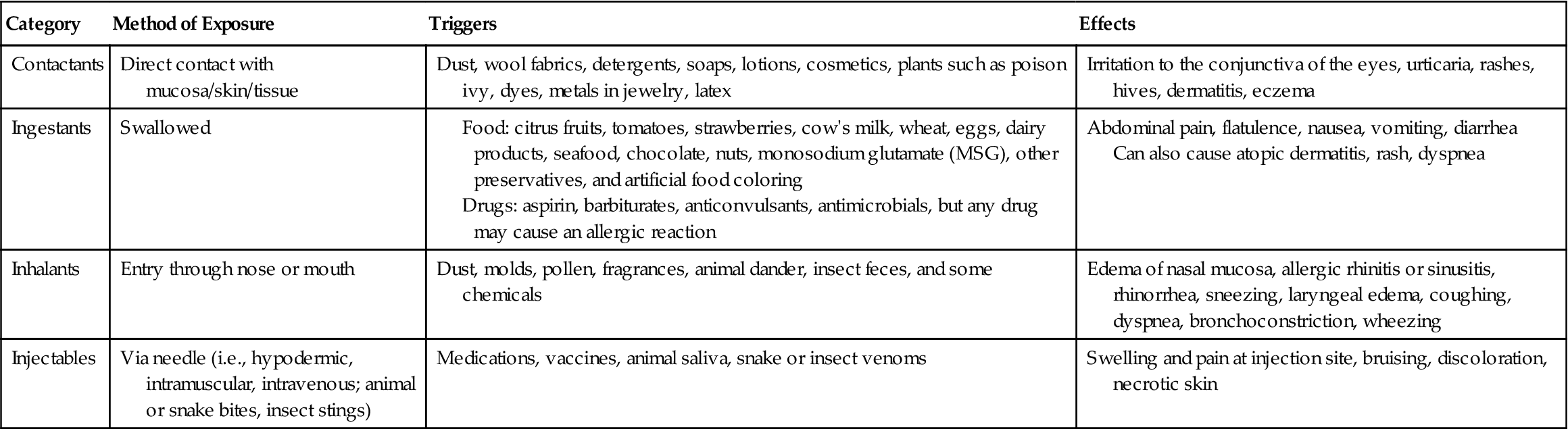

The body system most affected by the offending agent may present more specific symptomatology. For example, when the nose and eyes are exposed to a contact allergen, symptoms of itchy, red, watery eyes, soft palate pruritus, clear rhinorrhea, and sneezing are common. Should the allergen be inhaled, the release of histamine can cause the contraction of smooth-muscle tissues in the bronchioles of the lungs. These internal changes also produce an allergic response, notably erythema, edema, increased exudate, and breathing difficulties such as dyspnea and wheezing. Table 12-2 presents the four broad types of allergens.

Table 12-2

Four Broad Categories of Allergens*

*Any of the items mentioned can lead to severe allergic reactions including anaphylaxis and death if not recognized and treated immediately.

Diagnosis

Identification of Allergens

Identification of allergens can be a tedious process. Many times more than one substance produces the symptoms of an allergy. Reactions to certain food products, animals, insect stings, drugs, and other substances that are out of the norm are noticeable because of the relationship between cause and effect. Therefore the patient must be asked about exposure to substances that appear to or are known to cause an adverse response. The nurse should help the patient to recognize that vague symptoms, such as consistently becoming “stuffed up” at night could be an allergic reaction to her pillow.

Diagnostic Tests

Two primary methods are used to test for allergy. One is performing a radioallergosorbent test, known as RAST. This test uses blood serum from the patient to see if the IgE to the suspected allergen is present. The major advantages to this type of allergy testing are that antihistamine medications can continue; it is safer for patients with serious heart and lung problems; there is no chance of an anaphylactic reaction; it is more useful to identify a true food allergy; and it can be used when severe skin conditions prevent skin testing. The disadvantages to the RAST are that it is more expensive than skin testing; it can take several days to weeks before results are known; and it is less specific, meaning this test tends to produce more false-positive and false-negative results to other allergens.

Skin testing is also used in the diagnosis of allergies. The scratch test has been considered to be the most reliable method of allergy testing for more than 100 years. The skin is pricked by a needle and then a drop of the suspected allergen is applied to the area. A needle is then used to slightly scratch the skin just below the epidermis. The patch test is similar to the scratch test except the allergen is simply placed on the surface of the skin and covered with an airtight dressing (patch). For both of these tests, a negative reaction occurs when there is no erythema, swelling, or complaints of itching by the patient. A positive reaction to either of these tests is indicated by the appearance of a small (usually dime-size) wheal at the site of contact with the allergen and possibly by complaints of itching by the patient.

Drug Allergy

A patient may have a confirmed medication allergy, yet the medication is required and there are no alternatives. Before administration, a test dose of the drug may be given. For IV medications, a very small dose can be given and then, at 10-minute increments, increasing amounts of the drug are infused until the full dose ordered by the health care provider is administered. The nurse must continuously stay with the patient and closely monitor for signs and symptoms of a reaction during this process. Resuscitation drugs and emergency equipment must be immediately available. This same process is repeated with each subsequent administration of the medication.

Food Allergy

Even though other diagnostic methods are available to test for food allergies, a less expensive approach known as the elimination diet should be tried first. The patient should be taught to read product labels to identify offending substances used in the preparation or preserving of the food item. The patient is told to eliminate one food at a time and to keep a detailed diary, recording everything ingested each day, including the additives and preservatives in each food product. The patient should start with a food that is believed to be the cause of adverse reactions (e.g., itching, bloating). If symptoms persist for a week to 10 days after eliminating one food product (e.g., milk and dairy products), the patient would resume intake of that particular food, and choose another one for elimination.  This process continues until the offending food source is identified.

This process continues until the offending food source is identified.

Latex Allergy

Because many people have latex allergies, the nurse must be aware of whether the patient is allergic to latex. Most items routinely manufactured with latex are now being produced with non-latex alternatives, including gloves, Foley catheters, surgical drains, bandages, and condoms. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires that employers furnish personal protective equipment for their employees at no cost to the employee, and non-latex items should be made available for those with an allergy to latex. Severe latex allergies have caused some health care workers to change their work environment to one with little or no latex exposure.

Severe latex allergies have caused some health care workers to change their work environment to one with little or no latex exposure.

Treatment

Drug Therapy

Drugs that help alleviate the systemic reactions to allergens include epinephrine, antihistamines, bronchodilators, corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone), and cortisone (see Chapters 14 and 15 for specific drug information).

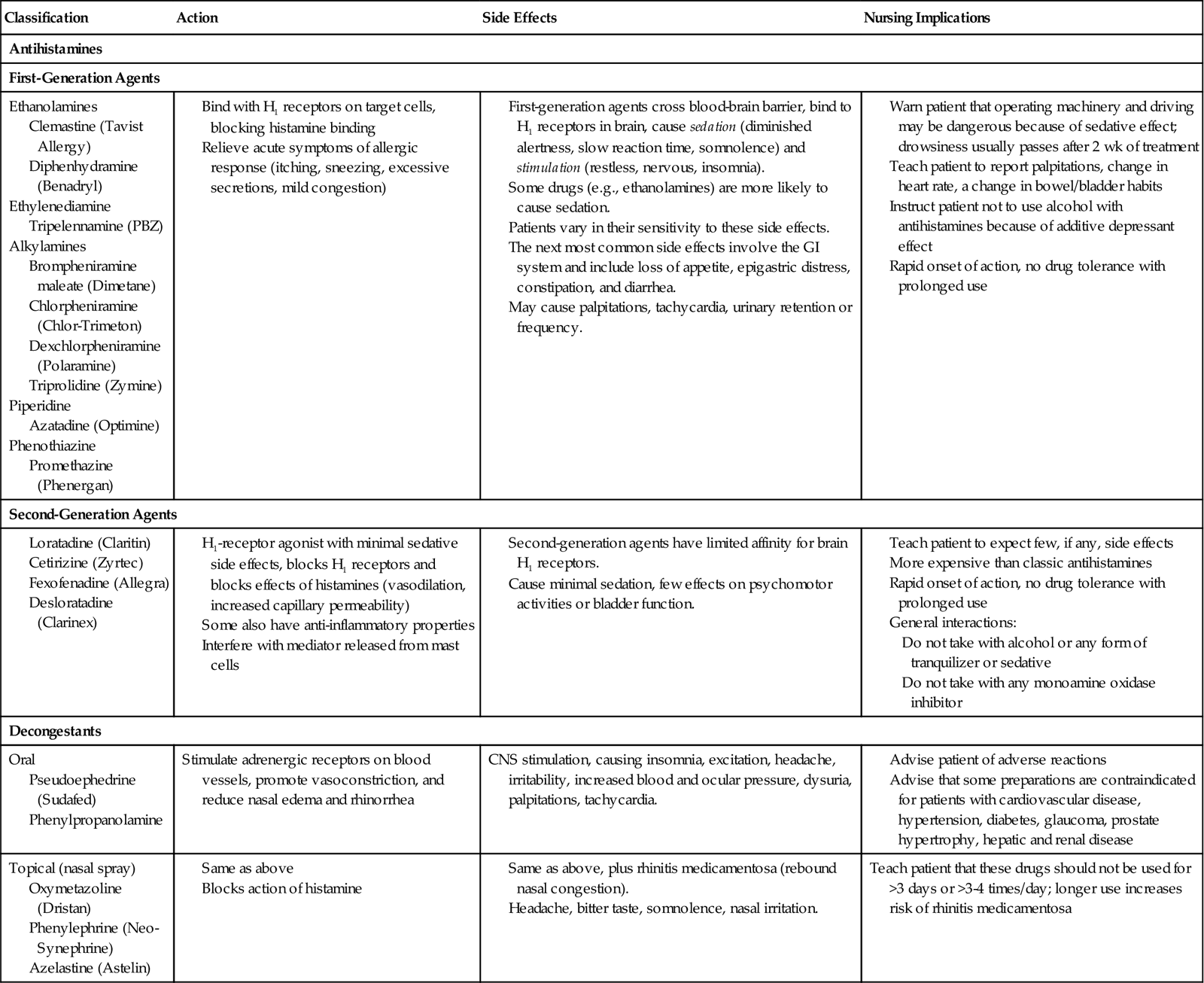

Antihistamines (histamine-blocking agents) help control the symptoms of hay fever and hives (Table 12-3) by preventing the release of histamine during an allergic reaction. The blocking action relieves itching, decreases swelling of mucous membranes and production of secretions, and reduces other symptoms of an allergic reaction. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) is commonly used orally and topically to counteract many allergic symptoms.

Table 12-3

Table 12-3

Drugs Commonly Used in the Treatment of Allergy

| Classification | Action | Side Effects | Nursing Implications |

| Antihistamines | |||

| First-Generation Agents | |||

| Ethanolamines Ethylenediamine Alkylamines Piperidine Phenothiazine | |||

| Second-Generation Agents | |||

| Decongestants | |||

| Oral | Stimulate adrenergic receptors on blood vessels, promote vasoconstriction, and reduce nasal edema and rhinorrhea | CNS stimulation, causing insomnia, excitation, headache, irritability, increased blood and ocular pressure, dysuria, palpitations, tachycardia. | |

| Topical (nasal spray) | Teach patient that these drugs should not be used for >3 days or >3-4 times/day; longer use increases risk of rhinitis medicamentosa | ||

Antihistamines can cause drowsiness and impaired coordination, so there are restrictions on driving an automobile and operating machinery at the beginning of therapy. Other common side effects include dry mouth, urinary retention, weakness, and blurred vision. Antihistamines and decongestants can aggravate hypertension and should be used with caution in patients who have high blood pressure. Elderly men taking antihistamines may experience hesitancy while voiding, urinary retention, and difficulty with ejaculation; the offending drug should be discontinued if the problem cannot be resolved.

Anti-inflammatory drugs such as corticotropin and cortisone are administered to reduce the inflammatory response that occurs in an allergic reaction. If the respiratory tract is involved, bronchodilators can be given to help relieve dyspnea and wheezing. Tranquilizers and sedatives may be ordered to promote the rest needed to successfully recover from a severe reaction and aid in relieving the stress that may have occurred. Local reactions involving widespread and deep skin lesions are treated with salves, wet compresses, and soothing baths. The patient must also be protected from a secondary bacterial infection.

Desensitization

When a patient cannot avoid exposure to allergens or if the symptoms cannot be managed successfully, the health care provider may suggest desensitization. The purpose is to decrease sensitivity to allergens. Regular injections of extremely small quantities of selected antigens are given daily, weekly, or monthly. The amount given is gradually increased until there is noticeable clinical improvement, and then a maintenance dosage is given. The program may last for years, but improvement should be noted in about 6 to 24 weeks after it is begun.

Nursing management

Assessment (Data Collection)

Identifying or isolating the allergens causing the patient’s symptoms requires time and diligence.