CHAPTER 10. Vascular Access and Fluid Replacement

S. Kay Sedlak

Fluid replacement is used for patients with subtle and overt volume losses. Solution, rate, and amount are determined by patient condition, underlying pathologic condition, and current fluid imbalance. Maintenance fluids are used for patients with little or no oral intake, whereas aggressive fluid replacement is indicated for patients with significant volume depletion. Patients with hematologic disorders, cancer, or hemorrhage may also require blood or blood product replacement. Vascular access options and various aspects of fluid replacement are described in the following sections.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

Low-pressure vessels located throughout the body receive blood from capillary beds and return it to the heart. Small venules flow into increasingly larger veins, which eventually flow into the inferior and superior vena cava. Vessel diameter varies among patients and with location in the body. Surface vessels in hands and arms are primary peripheral access points; however, vessels in the neck, legs, feet, and head may be used. Valves located within veins prevent backflow; therefore intravenous catheters must be inserted in the same direction as venous flow. Older adult patients lose collagen in vessel walls, which causes significant thinning over time. This may cause vessels to become fragile and “blow” when a catheter is inserted with a tourniquet in place. Vessels may also sclerose and become tortuous with aging.

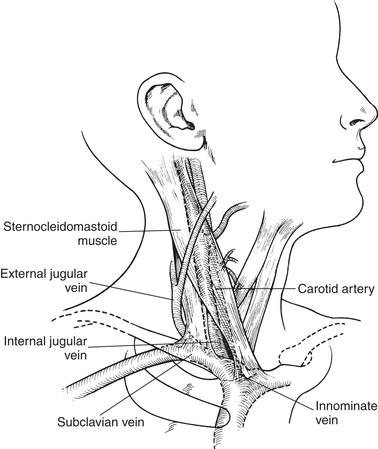

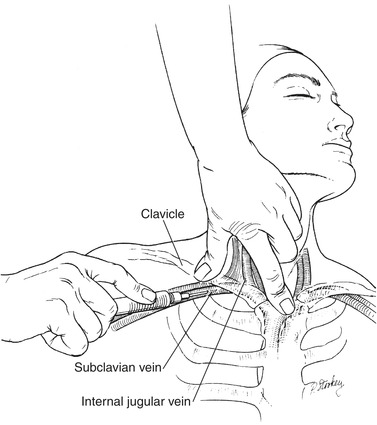

Peripheral veins of the neck flow into the subclavian vein and can be used for vascular access (Figure 10-1). The external jugular vein is visible in most patients on the lateral aspect of the neck. The internal jugular vein is located beneath and medial to the external jugular. Subclavian veins are used for access to central circulation.

|

| FIGURE 10-1 Veins in the neck. (Modified from Meeker MH, Rothrock JC: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 10, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.) |

VASCULAR ACCESS

Peripheral Venous Access

Inserting peripheral intravenous catheters is a routine skill for emergency nurses. Some agencies also allow nurses to insert central catheters, depending upon training and state regulations. This is not a basic skill for the majority of emergency nurses, however. Nurses assess, use, and maintain established vascular access sites. Catheters are usually inserted into peripheral veins of the hand, arm, or the external jugular veins of the neck. Vessels in the dorsal venous network of the foot and the saphenous vein are rarely used for routine vascular access in adults because of increased incidence of embolism and phlebitis, however, these veins are commonly used in infants.

Vascular access is obtained using aseptic technique. Initial insertion attempts should begin with distal veins and progress up the extremity. Proximal veins are not routinely used unless patients need immediate fluid replacement, such as trauma patients or patients in hypovolemic shock. During cardiac compressions, peripheral veins are used to avoid interruption in compressions, which upper-body central line insertion would require. To minimize the slower delivery of medications via this route, drug doses are followed by a rapid fluid bolus. Proximal peripheral veins are also used for patients receiving drugs that have an extremely short half-life and could become metabolized before reaching their target organ (e.g., adenosine) and for rapid boluses of contrast media required for specific imaging studies (e.g., spiral chest computed tomography [CT]). Scalp veins have no valves, so fluid can be infused in either direction; they are also easily visualized, making them an ideal alternative in infants.

Insertion of intravenous catheters is not without risk to the patient and the emergency nurse. Potential complications for the patient include infiltration of fluid/medications; phlebitis; embolism of blood, air, or catheter fragments; infection; and cellulitis. Catheters that are inserted under emergent conditions should be assessed to determine if appropriate aseptic technique was used. If it was not, the catheter needs to be replaced as soon as possible. The emergency nurse risks exposure to potentially infectious blood through a needle stick or direct contact with blood or body fluids. Extreme care should be taken to minimize risks through use of standard precautions and appropriate disposal of needles.

Catheter Selection

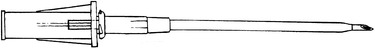

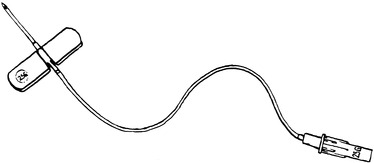

The size and type of catheter are determined by urgency of need and patient size, age, and vasculature. Blood should flow easily around the catheter after insertion. Larger diameter catheters are used for administering significant volume, colloid solutions, or blood or blood products, whereas smaller diameter catheters are used for routine vascular access. The smallest size and shortest length catheter that will deliver the prescribed therapy should be selected to decrease the potential for developing phlebitis. Catheters that are too large for a vessel can impede flow around the catheter and cause damage to the surrounding vessel wall. Catheters used for peripheral access include a straight catheter-over-needle design (Figure 10-2) and a butterfly or winged catheter (Figure 10-3). Catheters over needles are ideal for aggressive fluid replacement but can present problems with stabilization, particularly in distal veins of the hand. Winged catheters are easily inserted and can be stabilized with minimal effort; however, these catheters are not ideal for rapid fluid replacement. Their availability in smaller sizes increases their usefulness for pediatric and older adult patients. Unfortunately, they may be more uncomfortable than other catheters. Dual-lumen peripheral catheters must be flushed before insertion to activate a hydrolytic lubricant on the outside of the catheter. Intravenous catheters with safety features such as self-capping needles and retracting needles are readily available to decrease the health care worker’s potential exposure to bloodborne pathogens.

|

| FIGURE 10-2 Catheter-over-needle design. |

|

| FIGURE 10-3 Butterfly or winged infusion set. |

Insertion

Aseptic technique is essential to protect the patient from infection during intravenous catheter insertion. Gloves should be worn for site preparation and catheter insertion; additional precautions are required for central line insertion. The selected insertion site should have adequate circulation and be free of infection. Peripheral veins in hands and arms are the first choice for intravenous access. Other sites include veins of the lower extremities or the external jugular veins. The external jugular vein is accessible in most patients but requires turning the patient’s neck for access. Lowering the patient’s head distends the vein and decreases risk for air embolism during insertion. Use of the external jugular vein is not recommended for patients with suspected neck injury. Use of the internal jugular vein is contraindicated in these patients.

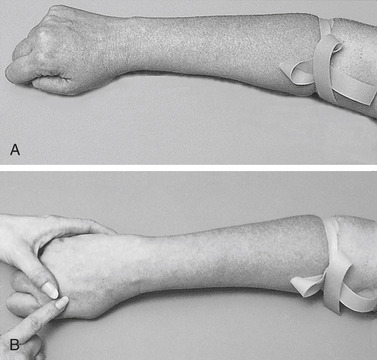

After an extremity site is selected, a tourniquet is placed proximally to distend vessels for easy insertion (Figure 10-4, A). Because veins may be more prominent in older adult patients, a tourniquet may not be required. Tourniquets may actually rupture vessels because of increased pressure in fragile veins. Gently tapping or rubbing vessels below the tourniquet increases vessel size by dilation. When vessels are not easily visualized or palpated, applying warm towels over the vein for 5 minutes causes vasodilation and can facilitate catheter insertion (Figure 10-4, B).

|

| FIGURE 10-4 A,Placement of tourniquet. B, Increased vessel size after application of warm towels. (From Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 5, St. Louis, 2001, Mosby.) |

Skin preparation begins with initial cleansing using a 2% chlorhexidine-based solution. 1 Alcohol or povidone-iodine (Betadine) solution may be substituted if necessary. The solution is applied directly over the insertion site in a back-and-forth motion. Allow the antiseptic solution to air-dry on the selected site before catheter insertion.

Local anesthesia is not routinely used for catheter insertion when time is an issue. However, after site preparation, lidocaine 1% may be injected at the insertion site for immediate anesthetic effect. A topical anesthetic (EMLA, LMX-4) can be applied over the insertion site as an alternative to injection if time allows—depending on the agent used, 30 to 60 minutes is required to achieve an anesthetic effect. Vapocoolant sprays may also be used to decrease the discomfort associated with catheter insertion, depending on institutional protocol.

After the site is prepared, the catheter is inserted by stabilizing the vein to prevent movement during puncture. With the needle bevel up, skin is punctured using the smallest angle possible between skin and needle (Figure 10-5). Veins may be entered on the top or side. The catheter and needle are advanced slowly until blood flashes into the catheter, then the catheter is advanced over the needle into the vein. The tourniquet is removed, and intravenous tubing is connected. One-way valves are recommended to prevent bleeding from the catheter during subsequent tubing changes. If fluid therapy is not required, catheters may be capped with a one-way valve and sterile cover. The catheter and tubing should be secured with tape according to hospital policy; however, tape should never be applied directly over the insertion site. A sterile, transparent, semipermeable dressing is recommended for application over the insertion site. Sites should be labeled with the date, time, catheter size, and initials of the person inserting the catheter.

|

| FIGURE 10-5 Venipuncture. (From Potter PA, Perry AG: Fundamentals of nursing, ed 5, St. Louis, 2001, Mosby.). |

Central Venous Access

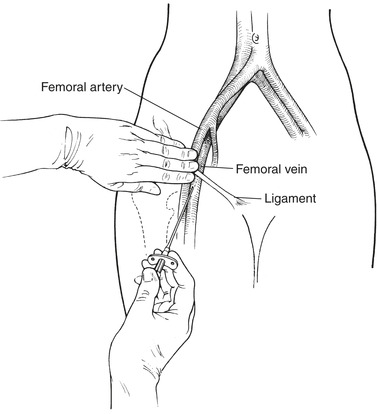

The subclavian, internal jugular, and cephalic veins are used for short- and long-term vascular access. Short-term central venous access is indicated when peripheral access cannot be obtained or when the patient’s condition requires hemodynamic monitoring. Long-term vascular access is indicated for prolonged intravenous therapy, total parenteral nutrition, extended antibiotic therapy, or therapy with caustic drugs such as vancomycin, and in patients with debilitating diseases such as cancer or acquired immune deficiency syndrome. To decrease the patient’s risk for developing a catheter-related infection, sterile surgical technique should be employed to insert these devices: the person inserting the line and the nurse assisting should be wearing sterile gloves and gown, mask, and cap with the patient draped from head to toe. In the ED, establishing central venous access is usually an emergent procedure that uses the subclavian or jugular veins. Figure 10-6 illustrates subclavian vein cannulization. Complications related to initial insertion include infection, hematoma, pneumothorax, and air embolism. The femoral vein located medial to the femoral artery may also be used for access to central circulation in some patients (Figure 10-7). The femoral vein is an excellent choice in cardiac arrest because cardiac compressions can continue during insertion. Access via the femoral vein also provides an opportunity for hemodynamic pressure monitoring. Complications associated with femoral vein access include hematoma and infection. Femoral sites should always be considered contaminated and replaced as soon as adequate alternative access can be obtained.

|

| FIGURE 10-6 Puncture of subclavian vein with needle inserted beneath middle third of clavicle at a 20- to 30-degree angle aiming medially. (From Daily EK, Schroeder JS: Techniques in bedside hemodynamic monitoring, ed 5, St. Louis, 1994, Mosby.) |

|

| FIGURE 10-7 Femoral vein. (Modified from Meeker MH, Rothrock JC: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 10, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.) |

Most central venous access catheters are made of silicone or polyurethane and have a radiopaque strip. Silicone is less thrombogenic than other materials and becomes pliable with moisture. Disadvantages of silicone include migration of the catheter tip and inability to withdraw blood over time as the catheter softens and collapses inward. Single-lumen and multiple-lumen catheters are available. Awareness of access ports and indications for each lumen is critical for appropriate management. The proximal lumen, which can be used for medication and blood component administration, can also be accessed for blood collection after infusates have been stopped for one full minute. 5 The distal port, which is generally larger, can be used to administer high-volume or viscous fluids, colloids, and medications. Some catheters have additional ports, which should be utilized according to manufacturer recommendations.

Patients may come to the ED with nonemergent, long-term access central lines in place. These include catheters that may be peripherally inserted, tunneled externally, or totally implanted (Table 10-1). Long catheters inserted peripherally in the cephalic or basilic vein can be left in place for 6 to 8 weeks. 2 The safe length of time to leave these catheters in place is steadily increasing. The midline catheter (MLC) ends just inside the subclavian vein, whereas a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) extends as far as the superior vena cava (Figure 10-8). Complications include infection and catheter migration. Tunneled external lines (Figure 10-9) and implanted ports (Figure 10-10) are used for long-term access, usually over months or even years. Implanted infusion ports are placed in the subcutaneous tissue, usually below the right clavicle or inner aspect of the upper arm. A catheter is threaded from the port through a large vein and into the superior vena cava. Only noncoring (e.g., Huber) needles are used to access the port. These catheters and ports should be flushed after each use with saline and then heparin per hospital protocol.

| N ote: New access devices are continuously being developed. | |||

| Nontunneled | Tunneled | Implanted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples | Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) and midline catheters (MLCs) | Hickman; Broviac | Hickman Port; Port-a-Cath; Norport; LifePort |

| Specific characteristics | Single lumen or multilumen; PICC lines are 60 cm long; MLC lines are 15-20 cm long | Single lumen or multilumen; Dacron cuff where tissue adheres helps ensure placement and decreases infection | Typically implanted in the chest wall; has a self-sealing septum; is accessed through skin with noncoring needle such as Huber needle to prevent damage to septum; special access catheter can be left in place, making repeated sticks unnecessary |

| Advantages | Does not require surgery for removal; easily removed or replaced | Unlimited use: painless when accessing; easily repaired when damaged; large gauge facilitates blood withdrawal | Less traumatic to body image; less maintenance; decreased chance of infection |

| Disadvantages | Activity restriction; no sutures so becomes dislodged easily; dressing needed at all times; maintenance costs are high because of frequent heparin flushing and injection cap changes | Mental and physical requirements for managing self-care; high maintenance cost; some patients cannot use this catheter because of body image (tube exiting the body) | High insertion costs; more painful in comparison with tunneled and nontunneled lines |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access