Kathleen F. Jett

Introduction to healthy aging

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE

I believe a human life is like a river, meandering through its course, rushing through rapids, flowing placidly over the plains, twisting and turning through countless bends until it spends itself. It is the same river; yet it looks very different from one place to another. So it is with our lives; circumstances vary from one time to another in the course of a life, but I think each stage has its own value.

Georgia, 35 years old

Caring for older adults gives us a unique opportunity to influence their quality of life in so many ways.

Nursing student, age 19

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

• Identify at least three factors that influence the aging experience.

• Define health and wellness within the context of aging and chronic illness.

• Describe the trends seen in global aging today.

• Apply Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to gerontological nursing.

Glossary

Cohort A Group in which members share some common experience.

Wellness A state of health that is optimal for the individual person at any point in time.

Centenarian A person who is at least 100 years of age.

Holistic health care That which considers the whole person and the interaction with and between the parts.

![]() evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

evolve.elsevier.com/Ebersole/gerontological

Providing nursing care to older persons is a rewarding, life-affirming vocation. Through this textbook we hope to provide students with the basics to begin a career as a gerontological nurse and care for older adults with more skill and sensitivity. We present an overview of aging, the most common health care needs of older adults, and the vital and exciting role of the nurse in facilitating healthy aging and wellness.

Aging in the United States

Although all of us begin aging at birth, both the meaning of aging and those who are identified as elders are determined by society and culture and influenced by history and gender. In the early American Puritan community of the 1600s, the process of aging was considered a sacred pilgrimage to God, and as such, persons in late life were revered. However, by the late 1800s, aging was devalued as youth became the symbol of growth and expansion. In 1935, with the establishment of Social Security, the time when one became “old” was set at 65. In the 2000s this age is creeping toward 70 along with the eligibility for retirement benefits.

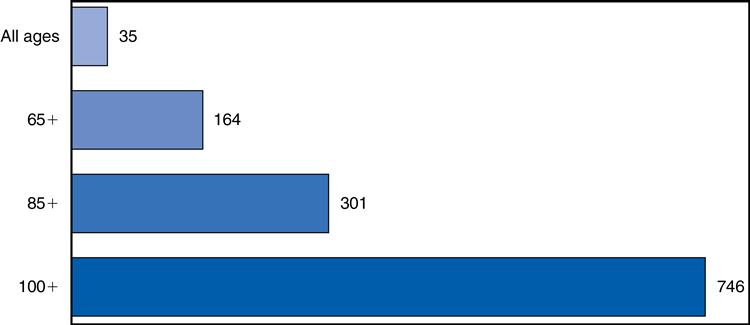

Psychologists have traditionally divided the “old” into three groups: the young-old, roughly 65 to 74 years of age; the middle-old, 75 to 84 years of age; and the old-old, or those over 85. Those 100 years of age and older (centenarians) are the most rapidly growing group today; those over 110 are referred to as supercentenarians (Willcox et al., 2008) (Box 1-1). In 2009 about 12.9% of the population in the United States or 39.6 million persons were 65 and over, compared with 0.1% in 1901. The total number is expected to double between 2000 and 2030, increasing to about 72.1 million or 19% of the population (Administration on Aging [AOA], 2011).

Those born within the same decade and country may share a common historical context and are referred to as a cohort. For example, men born between 1920 and 1930 were very likely to have been active participants in World War II or the Korean War. In comparison, men born between 1940 and 1950 were likely to have been involved in the Vietnam conflict, an entirely different experience. It is not surprising that these two groups of men have different perspectives and different health problems. Likewise, privileged women born between 1920 and 1930 were raised with what are known as traditional values and roles and may have either never worked outside the home or been limited to what was considered “women’s work,” such as housekeeping, teaching, and nursing. In contrast, similar women born between 1940 and 1950 had pressure to work outside the home and had considerably more opportunities, partially as a result of the feminist revolution of the 1960s and 1970s.

Gender can have a significant effect on various aspects of aging. Women usually live longer than men and live alone after widowhood. Men who survive their wives often remarry and live alone significantly less often than women. Women usually have larger social networks outside the work environment than men, which could potentially reduce social isolation after the death of a spouse or companion (see Chapter 24).

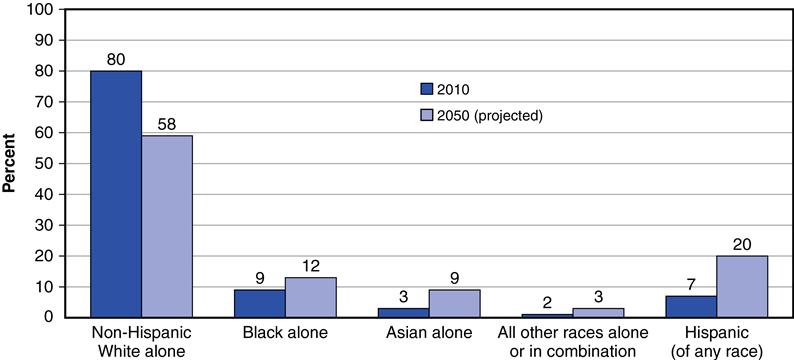

Finally, the United States is experiencing a “gerontological explosion” of all persons over 65, including ethnically diverse older adults. Persons comprising groups that have been considered statistical minorities in the late 1900s can now be considered an emerging majority as the relative percentage of their numbers rises rapidly. See Figure 1-1 for the projected changes in the demographics of older adults by ethnicity and race by the year 2050. Although the health status of racial and ethnic groups has improved over the past century, disparities in major health indicators between white and nonwhite groups are growing (Box 1-2). Increasing the numbers of health care providers from different cultures as well as ensuring cultural competence of all providers is essential to meet the needs of a rapidly growing, ethnically diverse elderly population (see Chapter 4).

Global aging

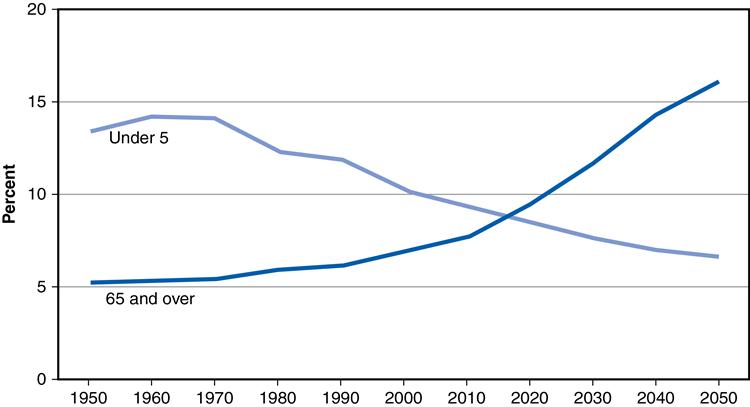

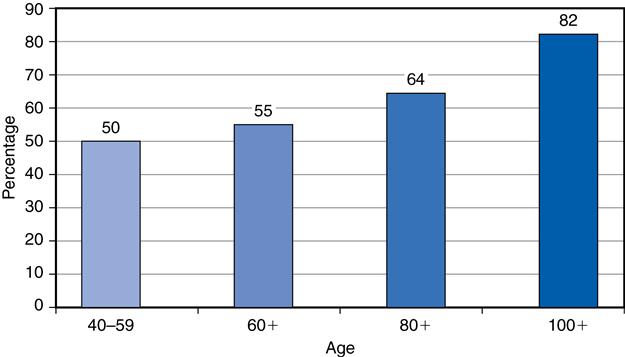

Before the year 2050, the number of persons 60 years of age and older worldwide is likely to exceed those younger than 15 years for the first time in recorded history, most notably in developing or low-income countries (National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, 2007) (Figure 1-2). This occurred in Europe in 1995 but will not occur in North America until 2015. Those older than 60 years of age will not surpass children until 2040 in Asia, Latin American, and the Caribbean (United Nations [UN], 2007a). However in 2007, Japan already had the highest percentage of persons 60 years of age and older at 27.9% (UN, 2007b). These changes pose major challenges in meeting the needs of the aging global community as the number of younger adults providing care and financial support diminishes. Although the number of the very old remains small, the relative number of centenarians in the world’s population is growing dramatically in the United States alone (Figure 1-3). The U.N. estimates that a worldwide population of 270,000 centenarians will grow to 2.3 million by the year 2050 (Kinsella & He, 2009, p. 28). Among centenarians, women are between four and five times more numerous than men (UN, 2007b, p. xxviii) (Figure 1-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree