- The role of the nurse in patient testing

- The five sub-disciplines of clinical pathology

- Clinical laboratory staffing and costs

Patients may be subjected to many kinds of investigative procedure. These range in complexity from ward or clinic based measurements familiar to all nurses, such as determining body temperature, pulse and blood pressure, through monitoring of heart function by electrocardiographic (ECG) machines to body imaging techniques, such as X-ray, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. All of these require the presence of the patient; they are performed on the patient, if not by nurses, at least often in their presence.

In contrast, all the investigations described in this book are performed on samples removed from the patient. The remoteness of patients from the site of laboratory testing might engender the understandable though misguided perception that laboratory testing has little to do with nursing care. In fact an understanding by nursing staff of the work of clinical laboratories is important for several reasons.

Nurses are in a unique position to satisfy the need expressed by many patients for information about the tests that they are subjected to. Recent research1 confirms the intuitive notion that patients want to understand the purpose of tests and significance of their test results. This may be to allay fears and anxieties among those who have never undergone such a test before, or it may simply reflect a right to know. Most laboratory tests are only minimally invasive but can only be done with a patient’s implied informed consent. Of course many patients will express no interest, but some have questions that must be addressed.

Nurses sometimes have responsibility for the collection and timely, safe transport of patient samples. It is vital that anyone collecting samples is aware of the importance of good practice during this pre-testing phase.

Nurses are frequently involved in the reception of laboratory test results. It is important that they are familiar with the terminology and format of laboratory reports and are able to identify abnormal results, particularly those that warrant immediate clinical intervention.

For many years nurses have performed limited testing of blood and urine samples (e.g. blood glucose and urine dipstick testing) in wards and clinics. With advances in technology, an ever increasing repertoire of tests can now be performed, within minutes, outside the laboratory in clinics and wards by nursing staff. This so called ‘point of care testing’ is particularly well established in intensive care, coronary care and emergency room settings where speed of analysis has proven benefit for patient care. It is important that nurses involved in the analysis of patient samples understand the pitfalls, limitations and clinical significance of this aspect of their work.

Traditionally, doctors have had sole responsibility for both requesting and interpreting laboratory test results, but the developing role of the clinical nurse specialist has required that some nurses become involved in both of these processes. In any case all qualified nursing staff members have to make judgements about how the results of laboratory tests might impact on the formulation of nursing care plans for their patients.

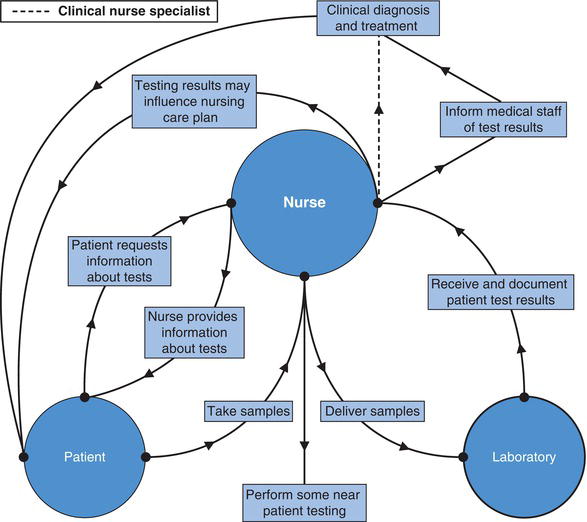

Finally, there are those nurses whose professional role requires especially detailed knowledge of the work of the laboratory as well as close co-operation with laboratory staff. These include haematology nurse specialists, blood transfusion nurse specialists, infection control nurses and diabetic nurse specialists. Figure 1.1 summarises the role of nursing staff in laboratory testing.

All the tests described in this book are performed – although, as has been made clear not exclusively so – in clinical pathology laboratories. The second part of this introductory chapter serves to describe in outline the work of the five sub-disciplines of clinical pathology. The range of samples tested is listed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Range of samples used for laboratory investigation.

| Sample type | |

| Chemical analysis | Usually blood or urine |

Less common:

| |

| Haematological analysis | Usually blood only Less common:

|

| Microbiological analysis | Common:

|

Less common:

| |

| Histopathological analysis | Tissue samples (biopsy) only |

| Cytopathological analysis | Urine Sputum Cellular material obtained by scraping the surface of organs or aspirating abnormal fluids (e.g. cysts) |

| Immunological analysis | Usually blood only |

The clinical chemistry laboratory

(also known as chemical pathology, clinical biochemistry)

Clinical chemistry is concerned with the diagnosis and monitoring of disease by measuring the concentration of chemicals, principally in blood plasma (the non-cellular, fluid portion of blood) and urine. Occasionally, chemical analysis of faeces and other body fluids, for example cerebrospinal and pleural fluid, is useful.

Blood plasma is a chemically complex fluid containing many inorganic ions, proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, hormones and enzymes, along with two dissolved gases, oxygen and carbon dioxide. In health the concentration in blood of each chemical substance is maintained within limits that reflect normal cellular and whole body metabolism. Disease is often associated with one or more disturbances in this delicate balance of blood chemistry; it is this general principle that underlies the importance of chemical testing of blood for the diagnostic process. The range of pathologies in which chemical testing of blood and urine has proven diagnostically useful is diverse and includes disease of the kidney, liver, heart, lungs and endocrine system. Diseases that result from nutritional deficiency can be identified by chemical analysis of blood. The cells of some malignant tumours release specific chemicals into blood. Measurement of these so called tumour markers allows a limited role for the clinical chemistry laboratory in the diagnosis and monitoring of some types of cancer.

The safe and effective delivery of some drug therapies depends on measuring the blood concentration of those drugs. This is just one aspect of the broader monitoring of treatment role that the clinical chemistry laboratory serves.

Most chemical testing of blood and urine is performed on highly sophisticated, automated machinery. Modern clinical chemistry analysers can perform up to 1000 tests per hour; 20 or more different chemical substances can be measured simultaneously on these analysers using a single blood sample. Results of the most commonly requested tests, which include nearly all those discussed in this book, are usually available within 12–24 hours of receipt of the specimen. More rarely, requested tests may be performed just once or twice a week, and a small minority are only performed in specialist centres. Nearly all clinical chemistry laboratories provide an urgent 24 hour per day service for a limited and defined list of tests; results of such urgently requested tests can usually be made available within an hour.

Critically ill patients being cared for in intensive care units and emergency rooms often require frequent and urgent monitoring of some aspects of blood chemistry. In these circumstances blood testing is performed by nursing staff, using dedicated analysers sited close to the patient; this represents one aspect of point of care testing.

The haematology laboratory

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree