Introduction

Nursing, as Jamieson et al (2002) suggest, is constantly evolving in an effort to meet the demands of health care in the 21st century. Central to that process is the need for nurses to deliver appropriate care in an educated and skilled manner (NHS Education for Scotland 2005). Given the increasing complexity in nursing roles and practice (Pearson et al 2005), the context within which the practice of nursing takes place is of paramount importance. This chapter will look at a variety of frameworks for practice that have been developed in order to assist that process. As it is recognised that this book will be used as a source of reference, rather than read from cover to cover, a broad overview of some commonly used traditional and contemporary frameworks are offered here. These are:

▪ Roper, Logan & Tierney model

▪ Orem’s self-care framework

▪ Team nursing

▪ Primary nursing and the named-nurse concept

▪ Evidence-based practice

▪ Multi-disciplinary working and integrated-care pathways.

Roper, Logan & Tierney model

As a starting point it is useful to look at the Roper, Logan & Tierney model of nursing. This model was introduced in 1980 and represents the first British conceptual framework for practice. It is still widely used while becoming increasing well known internationally (Pearson et al 2005). The model was developed at a time when clinical practice during pre-registration education was seen as ‘increasingly fragmented’ (Tierney 1998:78). There was a need to design a framework which assisted learners to ‘develop a way of thinking about nursing’ (Tierney 1998:79), that enabled them to provide effective and compassionate patient care within a variety of healthcare settings and to different patient/client groups whilst recognising their age, need and background (Roper et al 1980). It was regarded as a concerted attempt to move away from the bio-medical model that had prevailed up until that point (Tierney 1998) and as a vehicle for distinctive professional recognition (Wimpenny 2002).

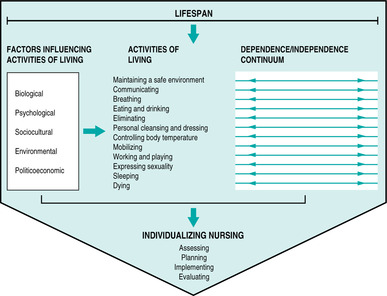

The framework itself is based on a ‘model of living’, which recognises an inextricable link between health, illness and lifestyle (Tierney 1998). The need for nursing intervention is normally considered to be on a short-term basis with an outcome emphasis on minimal disruption to people’s established lifestyles (Tierney 1998). Prevention rather than cure is promoted (Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). Roper et al (2001) acknowledge that it is impossible to represent the complexities of living in a simplistic model so they attempt to identify only the main features of it. Roper et al (2001:13–14) describe five main conceptual components:

1. Activities of living (ALs).

2. Lifespan.

4. Factors influencing the ALs.

5. Individuality of living.

The focus is on the individual and their participation in the process of living throughout their lifespan. People move in a unidirectional mode from birth to death and this progression can involve moving from a state of dependence to independence depending on age, circumstances and the environment (Pearson et al 2005).

To clarify the process of living further, twelve specific ‘activities of living’ are identified (Roper et al 1980). It is not the intention of this overview to address each of the activities individually; rather a broad-based consideration is provided. If you are interested in exploring them in greater depth, there are a number of texts by authors such as Aggleton & Chalmers (2000), Pearson et al (2005) and Roper et al (2001) themselves, which may be of use. The activities identified by Roper et al (1980) range from those that are essential to human life to those that enhance its quality. Some have a biological basis whereas others are more socially and culturally determined (Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). However, common to them all is the possibility that they may be influenced by physical, physiological, sociocultural, environmental and politico-economic forces (Pearson et al 2005). Consequently, a person will be affected by a unique range of influencing factors that determine the way he/she lives and how he/she experiences illness.

Use of a concept such as ‘activities of living’ has the advantage of being familiar to a variety of allied health professionals and as such is important for reminding nurses that they are part of a wider multi-disciplinary team, capable of delivering optimum standards of care (Jamieson et al 2002). However, in order to gain an appreciation of how the model appears when all the contributing dimensions are placed together, it is easiest to view a diagrammatic representation of it (Fig. 1.1).

|

| FIGURE 1.1The model of nursing |

Application of the model directs nursing intervention towards the process of ‘helping people to prevent, alleviate, solve or cope with problems (actual or potential) related to the Activities of Living’ (Roper et al 1990:37 cited in Tierney 1998:79). The framework makes explicit the relationship of the practice of nursing to the individual patient and the wider theoretical base of nursing (Jamieson et al 2002). While the model may not be considered to be highly original as it draws upon ideas contained within Henderson’s classic definition of nursing (Tierney 1998), it is to be appreciated for its clarity, providing an enduring contribution for nurses to take forward (Pearson et al 2005).

Orem’s self-care framework

In a similar, but slightly different context to that of Roper, Logan & Tierney’s model, a framework for nursing emerged from the USA that also focused on individual independence. This framework is also widely used and is deemed to be popular with British and American nurses alike (Pearson et al 2005). The work of a well-known and respected nursing theorist, Dorothea Orem, the framework was also developed in a climate where external influences on nurse education programmes such as medicine prevailed (Phillips 1977 cited in Fawcett 2000) and where there was a need to identify nursing as a discrete art and science (Fawcett 2000).

The framework, which was first published in 1971, is similar to that of Roper, Logan & Tierney in so far as it draws upon the theory of human needs (Meleis 1991 cited in Pearson et al 2005), however it differs in the interpretation of ‘independence’. For Orem (1995) the notion of independence may be regarded as ‘self-care’ focusing on the ability humans have to be self-determining. People endeavour to be self-caring either on their own merits or with the assistance of friends or family (Walsh 1998). An inability in any area preventing the achievement of this goal would result in a ‘self-care deficit’ requiring nursing intervention (Walsh 1998). Interestingly, it is not only the ability to self-care that is important for Orem, but also the ability to care for others. Her model considers the capacity to care for others as integral to human behaviour (Walsh 1998) and in this sense legitimises the role of the nurse.

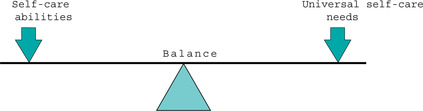

People within Orem’s framework are regarded as whole entities rather than the amalgamation of a number of subsystems (Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). They are capable of independent thought and action giving them the potential to acquire the knowledge, skills and motivation to care for themselves, their families and dependants. This capacity to self-regulate life, health and wellbeing is referred to as ‘self-care agency’ (Cox & Taylor 2005) and is dependent upon a number of factors including age, gender, developmental stage, socio-economic status, cultural orientation, environmental influences and adequacy of resources (Orem 1991 cited in Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). The acknowledgement of influences upon the individual in relation to health is similar to the Roper, Logan & Tierney model, but instead of the individual moving along a dependence/independence continuum, a balance is sought between needs and abilities. When a mid-point is reached, which is of equal weighting either side, a state of health is deemed to have been achieved (Fig. 1.2).

|

| FIGURE 1.2A healthy individual |

Like the Roper, Logan & Tierney model, Orem identifies a significant number of needs, which she entitles ‘universal self-care needs’. She identifies eight in total encompassing physical, psychological and social dimensions. However, in contrast to Roper, Logan & Tierney, Orem does not specify any particular way of meeting these needs and accepts that individuals will vary in the extent to which they may wish to satisfy them (Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). Indeed, her theory of self-care deficit proposes that individuals need to undertake a number of actions in a timely and adequate manner each day to maintain their health, life and well-being (Cox & Taylor 2005).

In addition to universal self-care needs, health deviation and developmental self-care needs are identified within Orem’s framework (Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). Health deviation self-care needs reflect the extra demands placed on the ability to self-care by illness, while developmental self-care needs acknowledge an individual’s stage of growth and development (Aggleton & Chalmers 2000). The need for nursing intervention, therefore, arises when any of these needs (singly or in combination) shift the balance away from the healthy mid-point previously described.

The diversity of dependency acknowledged within the framework indicates that nurses not only have a caring role, but they may also be required to be a health educator (Walsh 1998). It is a framework, therefore, that finds appeal from healthcare professionals working in the areas of health promotion and disease prevention alike (Pearson et al 2005). This is an important consideration given contemporary thinking about nursing and its future direction (Royal College of Nursing 2004). Similarly, the framework places a focus on the family (Taylor 2001) and in that respect reflects the current World Health Organization (WHO) ‘Health for all’ policy framework (World Health Organization, 1998), which is receiving widespread interest and attention.

While what appears here may be viewed as simplistic, it is worth noting that, in reality, Orem’s framework is a complex one and should not be underestimated. For a more detailed insight into the framework, authors such as Fawcett (2000) and Marriner Tomey & Alligood (2005) are advised. Equally, the frameworks discussed so far are not in themselves exclusive, there are others including Roy’s adaptation model (1976), Neuman’s systems model (1982), King’s goal-attainment model (1981) and Peplau’s developmental model (1952), to name but a few. While acknowledging their importance, these models tend not to be encountered as frequently as those mentioned above and as such are not discussed here.

The development, by theorists, of models and frameworks for practice in nursing are important as they offer clarity and identity (Tierney 1998), however they are not the only frames of reference used by nurses when practising (Fawcett 2003). Historically, nursing has been organised either by assigning patients or tasks (Tiedeman & Lookinland 2004). One approach that has utilised both is team nursing. Team nursing emerged in the 1950s as a model of care delivery that eased the shortage of nurses following World War II while utilising the available, differing levels of skilled healthcare workers (Tiedeman & Lookinland 2004). The model of care requires the formation of a team led by an experienced, qualified member of nursing staff (Brooker & Nicol 2003). The underlying philosophy is that a team of people working collaboratively together can deliver better quality care than the same group of individuals working independently (Tiedeman & Lookinland 2004).

The team is responsible for the care of a group of patients throughout their stay in hospital (Brooker & Nicol 2003) and, as such, has a collective responsibility for all aspects of the patients’ care. The focus of the duties by team members, as indicated previously, may be task or patient orientated depending on the style of implementation adopted by the team leader (Tiedeman & Lookinland 2004). The team leader allocates care duties in accordance with the complexity of the patient needs and the level of ability of the caregiver (Tiedeman & Lookinland 2004). While being an attractive framework for practice, as it acknowledges and effectively utilises the skill mix within contemporary healthcare, it is also open to some criticism. A team’s responsibility to its patients lasts only for the duration of its shift and a patient–team assignment may vary from shift to shift or adopt a permanent team allocation for the duration of the hospital stay (Tiedeman & Lookinland 2004). This disparity, along with the differing modes of deployment of staff, may lead to care of a variable standard and quality. Equally, the fact that the team, and not a named individual, has responsibility for all aspects of patient care can create a vagueness surrounding the line of accountability (Brooker & Nicol 2003). Not withstanding these weaknesses, it is a framework for practice that is still widely used and readily recognisable on entering clinical areas.

Primary nursing and the named-nurse concept

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree