Mary Ellen Murray, PhD, RN

Economics of the Health Care Delivery System

Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhuman.

—MARTIN LUTHER KING JR

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define economics and health care economics.

• Compare the market for health care to a normal market for goods and services.

• Use a basic knowledge of health care economics to analyze trends in the health care delivery system.

• Describe what is meant by operating budget, personnel budget, and capital budget.

• Define economic research strategies.

• Describe what is meant by the term fiscal responsibility in clinical practice.

• Discuss strategies you will use to achieve fiscal responsibility in your clinical practice.

The rate of increase in national health care spending slowed to 4.4% in 2008—the slowest rate of increase in 48 years (Hartman et al, 2010). However, it may not be time to celebrate! In 1995, national health care expenditures (NHCE) topped $1 trillion dollars for the first time. The 2008 figure represents NHCE of $2.3 trillion, more than doubling the 1995 figure in 3 years. By the year 2018, those expenditures are projected to exceed $4.3 trillion dollars. In 2008, the national health care expenditures consumed 16.2% of the gross domestic product (GDP, the value of all the goods and services produced in the United States annually). The percentage of the GDP devoted to health care is predicted to be 20.3% by 2018 (NHCE projections, 2008-2018). The outcome of this investment, in terms of the public health of the population, is a nation lagging behind many comparable industrialized nations. In 2010, an estimated 45 million persons were without health insurance. Prescription drug coverage under Medicare is limited. Great disparities in access to health care exist among racial and ethnic populations. There are vast differences in the reimbursement for the treatment and care of physical and mental illness (Murray, 2002). All of these statistics have implications for the clinical practice of nursing.

What Are the Trends Affecting the Rising Costs of Health Care?

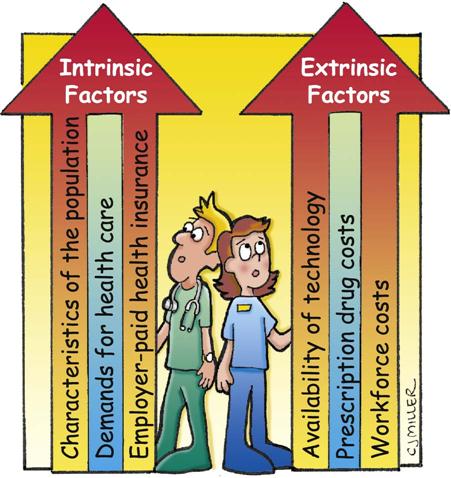

Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors contribute to rising costs of health care. Intrinsic factors include characteristics of the population (the population is getting older and requiring more of the health care system), the demand for health care, and employer-paid health insurance. Extrinsic factors include the availability of technology, prescription drug costs, and workforce costs (Figure 16-1). The recession facing the United States, and the world, in 2009 to present has both intrinsic and extrinsic effects.

Intrinsic Factors

The U.S. population grew by 32.7 million people from 1990 to 2000, the largest increment in American history (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006). Population estimates for the years 2008 to 2009 projected a 9% increase. Population projections for the years 2000-2010 predict a growth of almost 27 million people, with the greatest increase among the 45- to 64-year-old age group. This is important information because older people typically use increased health care resources and may not have the income to purchase them.

Over the projection period of 2009-2019, the Baby Boomers (citizens born between 1946 and 1964) will become eligible for Medicare health insurance. “Provisions of the Affordable Care Act are projected to result in a lower average annual Medicare spending growth rate for 2012 through 2019 (6.2%), 1.3 percentage points lower than pre-reform estimates” (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010, p 2). There is also an increasing demand for health care in the United States. Demand, in the economic sense, is the amount of health care services that a consumer wishes to purchase. Another aspect of increased demand for health care has to do with the widespread availability of health insurance. This has the effect of lowering the cost of health care to individuals who have health insurance. In contrast with demand for health insurance, the need for health care is defined as the amount of health care that the experts believe a person should have to remain as healthy as possible, based on current medical knowledge (Feldstein, 2004). The question then arises: Should the amount of health care provided be based on need or demand?

Extrinsic Factors

The availability of new medical technology has contributed to the rising costs of health care. If an institution does not offer technology that a competitor offers, it is likely that the market share (percentage of persons in an area selecting that institution) of the institution will decline. To attain a competitive edge, an institution needs to be an early adopter of expensive, new technology. Then, thinking sequentially, someone has to pay for the technology, and this cost will be passed on to consumers in the form of higher health care costs.

Prescription drug care costs are projected to rise from a projected $219 billion (2006) to $299 billion in 2010, to $446 billion in 2015 (Borger et al, 2006). The major impact of the Medicare prescription drug program is a shift in payment for the drugs from private sources to the government.

A final factor driving health care costs is the increase in hospital care expenditures, which were projected to be $663 billion in 2006 and $882 in 2010 (Borger et al, 2006). One of the main factors contributing to these increases is rising labor costs. Although this is good news for the nursing profession, it is part of a national problem.

The current recession in the United States has decreased private health spending and increased in Medicaid enrollment and expenditures. Similarly, economists project a decrease in hospital prices due to a weakening demand for hospital services, again related to the recession. There is also a projected decrease in the private insurance sector in prescription drug growth, as many consumers either fill fewer prescriptions or become more willing to use lower cost generic drugs. However, Medicare and Medicaid prescription drug spending will offset the private sector recession related decrease.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social, and environmental challenges of globalization (OECD, 2007). This group reports statistics related to health expenditures and outcomes. In 2007, the United States was reported to spend 16% of the GDP for health care for every man, woman, and child in the country. The country nearest to the United States that year was France at 11% of the GDP.

What Is the Effect of the Changing Economic Environment on Clinical Practice?

Because nurses belong to the largest health care profession and are thus in a position to influence health care costs, it is essential that all nurses understand basic concepts of economics and fiscal (money) management. This knowledge was previously taught in graduate courses for nurse managers or nurse executives. However, the world has changed! One nurse author (Hunt, 2001) states, “Clinical competency is not the only tool needed in an era when economics dominates the health care arena” (p 11).

Introduction to Economics

A simple definition of economics is the allocation of scarce resources. An analogy might be made to the income that an individual earns. The paycheck is a limited, finite amount of money, and choices must be made about how to spend, or allocate, the money. Such choices might include rent, a car payment, food, clothing, and health insurance payments. Individuals may not be able to pay for all of the goods or services that they wish to have, so decisions must be made and priorities established.

Similarly, health care is a limited resource, and choices have to be made. The choices about health care that concern economists are made at the national level. Questions to answer include these: How much does the country wish to spend on health care, what services does the country wish to provide, what is the best method for producing health care, and how will health care be distributed (Feldstein, 2004)?

What Are the Choices About Amount of Spending?

Currently, the United States is spending slightly more than 16% of its income on health care. As the payer for Medicare (the national health insurance program for people aged 65 years or older, some people younger than age 65 with disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease) and Medicaid (a joint federal and state program that pays for medical assistance for certain individuals and families with low incomes and resources), the federal government is the nation’s largest purchaser of health care. Yet this amount does not fully meet the needs of the populations served under these programs, let alone provide for the health care needs of persons without insurance.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010

Congress and President Obama signed into law the Affordable Care Act of 2010. This type of health care reform is anticipated to provide health care coverage at an affordable cost for all Americans.

What Are the Choices About Services to Provide?

Oregon State passed legislation between the years 1989 and 1995 that provides an example of choices about the services provided to persons with Medicaid coverage. Consumers and providers of health and social services were charged with developing a ranked list of health care services in order of their benefit to the entire population being served and to reflect community values. Coverage for all conditions at a certain level would be set by the state legislature dependent on budget constraints. In the listing of services, treatment of, for example, premature infants, cleft palate, hip fracture, or stroke was covered, whereas radial keratotomy, cosmetic dentistry, and treatment of varicose veins were not included (Oregon Health Policy and Research, 2004). Although this is one type of rationing of health care and Americans are typically opposed to any type of rationing system, it must be noted that the services denied under the Oregon plan are consistent with those denied reimbursement under other private and public insurance plans (Critical Thinking Box 16-1).

Like physicians, rationing of care is an important issue facing the nursing profession. The International Hospital Outcomes Study considered rationing of nursing care. Researchers in Switzerland (Schubert et al, 2008) explored the association between the implicit rationing of nursing care and patients outcomes in Swiss hospitals. They found that despite low levels of rationing of nursing care, it was a significant predictor on all six patient outcomes that were studied.

What Are the Choices About Methods to Produce Health Care?

One informal definition of managed care is this: the right care, in the right amount, by the right provider, in the right setting. This definition implies that there are several ways to produce health care. For example, a woman may choose to have an annual physical examination by a nurse practitioner, a certified nurse-midwife, a gynecologist, or a family practice physician. Each provides care from a different perspective and at a different price. In another example, certain procedures that were once done only in hospitals are now done in an outpatient setting, many with the addition of home health nursing. Lumpectomy and simple mastectomies are surgical procedures that are now done in an outpatient setting and that illustrate a different method of producing health care. Deciding the best method is subject to research and must include an analysis of the costs.

What Are the Choices About Allocation?

These decisions involve “who gets what.” The underlying question is this: Is health care a right or a commodity (like cars or clothing) to be allocated by the market place? The World Health Organization (WHO) states in its constitution that the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being (WHO, 2004). The American Nurses Association Health System Reform Agenda (2008) also affirms that health care is a basic human right and that a health care system that ensures universal access to essential health care services is essential. In another document, the ANA (Code for Nurses, 2001) states that nurses should provide care without consideration of the patient’s social or economic status. However, even if one believes that health care is a right, challenging questions remain. How much health care is a right? Who pays for the health care of people who cannot afford it? Let us assume that an instructor is teaching senior nursing students who all agree that health care is a right. The instructor then asks the students how much of their paycheck they would be willing to forfeit in taxes so that everyone could have this right of health care. It is rare that students are willing to subsidize others’ health care at a cost of more than one-third of their own salary.

Even beyond the costs of care is the question of allocation decisions—that is, who decides who gets what health care. Several responses are possible: the government, payers of health care, individuals, the market place, and rationing systems.

Government Allocation Decisions.

Through its funding of Medicare, the government has made multiple allocation decisions. The U.S. government has decided it will pay for inpatient health care and some outpatient care for patients older than 65 years of age and selected others. Unfortunately, many of the persons covered by Medicare have come to believe that Medicare covers “everything,” and this is not so. It is particularly challenging to nurses when elderly patients assume that they “have Medicare” and thus “nursing home care is paid for.” This is a frequent misinterpretation of Medicare coverage. There are many limits to the services reimbursed by Medicare and many requirements that must be met before the government will make payment (Critical Thinking Box 16-2).

Payer Allocation Decisions.

All insurance companies have rules about the services that will be covered and the requirements that must be met under their policies. One rule involves the presence of preexisting conditions. If, for example, a patient has been diagnosed with AIDS or has been treated for mental illness, that person may be denied coverage for treatment of that particular condition—or denied coverage altogether. When the insurance is a benefit of employment, this is less likely to occur. At other times, if an individual is applying for insurance, she or he may be required to fill out a lengthy questionnaire about health history or submit to a physical examination. The findings of these resources may be used to deny or limit coverage.

Once an insurance policy is in effect, there are additional rules regarding the services that will be covered. Most policies require preauthorization (pre-approval) of services before the patient receives care, except in cases of emergency. For example, a physician’s office will typically communicate the need for a surgical procedure to the insurance company and obtain this approval. If the patient is admitted to the hospital in an emergency, however, this requirement is normally waived and the hospital has a limited amount of time to gain the approval or reimbursement for the care may be denied.

Another restriction on resource allocation involves the process of concurrent utilization review (UR). This is a strategy used by managed care companies to control both costs and quality. The process requires that hospital staff, typically registered nurses, communicate the plan of care for a hospitalized patient to the payer or their representative. The payer then determines whether the care is appropriate, medically necessary, and covered under the terms of the policy or the contract with the provider (Murray & Henriques, 2003). For example, if a patient is admitted to the hospital the day before elective surgery, that day’s cost will almost certainly be denied reimbursement. Preoperative patient teaching and surgical preparation can be done on an outpatient basis at a much lower cost than a day in the hospital.

Marketplace Allocation Decisions.

A final alternative for the allocation of resources is the marketplace. This decision making implies that health care is a normal good, like a car or a piece of clothing, where an increase in income leads to an increase in demand for the good, and the rules of supply and demand apply. However, the market for health care has some significant differences from the market for normal goods.

Unpredictability of Demand.

The first difference in the market for health care is the unpredictability of demand. When a person is well, there is little demand for health care services. There is a great demand for health care when a person is ill, and the timing of illness is, of course, uncertain. Consider for example, the case of a patient needing a heart transplant. A patient does not wait until the price comes down. Rather, the surgery is purchased at any price if a donor heart is available.

Consumer Knowledge.

Another difference in the health care market involves the knowledge of the consumer. If an individual is purchasing a coat or a car, the person usually knows a good deal about the item being purchased or consults Consumer Reports for further data. This is not the case in health care, about which patients tend to have limited knowledge and limited ability to interpret the available knowledge.

Barriers to Entry to the Market.

Even if patients had sufficient knowledge to treat their own illnesses, the health care market is fraught with barriers. All providers must pass examinations and be licensed by appropriate boards. Prescriptive authority is heavily regulated and closely controlled.

Lack of Price Competition.

The health care market, unlike the market for clothing and automobiles, does not engage in price competition. When, for example, have you heard of a sale on appendectomies or “2 for the price of 1” hip replacements? Of course, it does not happen. But more problematic is the fact that health care consumers frequently do not know the cost of their care—especially if it is being paid for by an insurance provider. In fact, many consumers indicate that they “never saw a bill” for their hospitalization. This is considered to be a measure of the quality of their insurance. Is there any other product that would be routinely purchased without knowledge of its price? The lack of this knowledge leads to predictable consumer health care purchasing behavior.

The classic Rand Health Insurance Experiment (Keeler & Rolph, 1983) was a controlled research study that examined the effect of different co-payments on the utilization of health care. Participants in the study either received free care or paid co-payments of 25%, 50%, or 95%. Economic theory would predict that as price increases, the purchase of goods or services would decline. That is exactly what happened. With a co-payment of 25%, there was a decline in utilization of health care of 19% compared with a free plan. There were even greater declines in utilization of health care services at the higher rates of co-payments. This consumer behavior is so predictable that health care economists have a term for it: moral hazard. It refers to a situation in which a person uses more health care services because the presence of insurance has lowered the price to the person.

A final method of allocating health care resources is some system of rationing. Rationing is a type of allocation decision that suggests a need-based system. One author defines rationing as a decision to “(1) withhold, withdraw, or fail to recommend an intervention; (2) informed by a judgment that the intervention has common sense value to the patient; (3) made with the belief that the limitation of health care resources is acute and seriously threatens some members of the economic community; and (4) motivated by a plan of promoting the health care needs of unidentified others in the economic community to which the patient belongs” (Sulmasy, 2007, p 19). Americans find this inherently distasteful. One example of a rationing decision is to not perform heart transplants on patients over 65 years of age with the rationale that the money could be spent on, for example, well-child immunization programs. The major ethical questions (Sulmasy, 2007) involved in rationing decisions include (1) Who makes the decision and (2) using what criteria? However, most Americans find the concept of rationing inherently unacceptable. The counterargument to this position is that rationing occurs every day in the U.S. health care system, but the decision is currently made on the basis of the individual’s ability to pay for care.

Budgets

A budget is a tool that helps to make allocation decisions and to plan for expenditures. It is important that staff nurses understand budget processes because these decisions directly impact their clinical practice. For example, staff nurses working on a patient care unit may feel that there is not enough time to care for acutely ill patients on the unit. A clinical manager may respond that the “budget will not allow” additional staff. The reality is that the budget is a human made planning tool and must be flexible in order to be useful. Savvy staff nurses will understand the budget process and be able to relate patient acuity to staffing needs. To engage in these discussions, all nurses need to understand basic concepts of budgets as well as different types of budgets: capital budgets, operating budgets, and personnel budgets (Figure 16-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree