V

VAGAL MANEUVERS

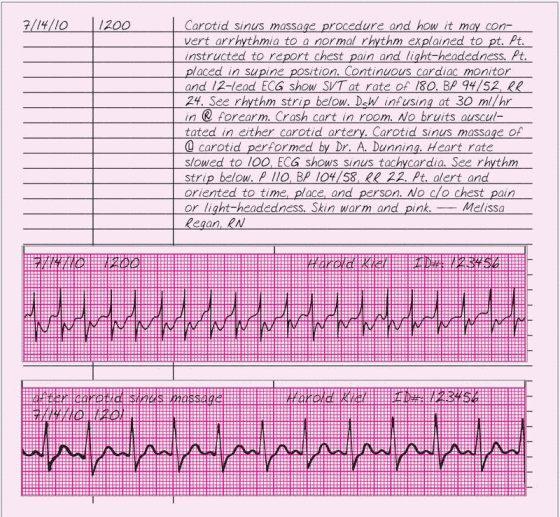

When a patient suffers sinus, atrial, or junctional tachyarrhythmias, vagal maneuvers—Valsalva’s maneuver and carotid sinus massage—can slow his heart rate. These maneuvers work by stimulating nerve endings, which respond as they would to an increase in blood pressure. They send this message to the brain stem, which in turn stimulates the autonomic nervous system to increase vagal tone and decrease the heart rate. Usually performed by a doctor, vagal maneuvers may also be performed by a specially trained nurse under a doctor’s supervision.

In Valsalva’s maneuver, the patient holds his breath and bears down, raising his intrathoracic pressure. When this pressure increase is transmitted to the heart and great vessels, venous return, stroke volume, and systolic blood pressure decrease. Within seconds, the baroreceptors respond to the changes by increasing the heart rate and causing peripheral vasoconstriction. When the patient exhales at the end of this maneuver, his blood pressure rises to its previous level. This increase, combined with the peripheral vasoconstriction caused by bearing down, stimulates the vagus nerve, decreasing the heart rate.

In carotid sinus massage, manual pressure applied to the left or right carotid sinus slows the patient’s heart rate. The patient’s response to carotid sinus massage depends on the type of arrhythmia. If he has sinus tachycardia, his heart rate will slow gradually during the procedure and speed up again after it. In atrial tachycardia, the arrhythmia may stop and the heart rate may remain slow. With atrial fibrillation or flutter, the

ventricular rate may not change; atrioventricular block may even worsen. Nonparoxysmal tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia won’t respond to carotid sinus massage.

ventricular rate may not change; atrioventricular block may even worsen. Nonparoxysmal tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia won’t respond to carotid sinus massage.

VENTRICULAR ASSIST DEVICE

A temporary life-sustaining treatment for the failing heart, the ventricular assist device (VAD) diverts systemic blood flow from a diseased ventricle into a centrifugal pump; thus temporarily reducing ventricular work, which allows the myocardium to rest and contractility to improve. The

VAD functions somewhat like an artificial heart. The major difference is that the VAD assists the heart, whereas the artificial heart replaces it.

VAD functions somewhat like an artificial heart. The major difference is that the VAD assists the heart, whereas the artificial heart replaces it.

The permanent VAD is implanted in the patient’s chest cavity, although it still provides only temporary support. The device receives power through the skin by a belt of electrical transformer coils (worn externally as a portable battery pack). It can also be operated by an implanted, rechargeable battery for short periods of time.

Candidates for the VAD include patients with massive myocardial infarction, irreversible cardiomyopathy, acute myocarditis, an inability to be weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass, valvular disease, bacterial endocarditis, or heart transplant rejection. The device may also be used in patients awaiting a heart transplant.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of your entry. Note the patient’s condition after the insertion of the VAD. Record the results of your cardiopulmonary findings (including hemodynamic measurements) as well as neurologic and renal assessments. Document pump adjustments and the patient’s response. Chart signs and symptoms of poor perfusion and ineffective pumping (such as arrhythmias, hypotension, slow capillary refill, cool skin, oliguria or anuria, or anxiety and restlessness), pulmonary embolism (such as dyspnea, chest pain, tachycardia, productive cough, or low-grade fever), and stroke or neurologic deficits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree