Strategies for NPs

The difference between making do and advancing is the difference between eating all of what is put on one’s plate and deciding what to have for dinner.

NPs faced with restrictive or outdated law sometimes report at professional meetings that they are proud of how they are able to function despite the law. For example, NPs who want to have their own businesses can construct a private practice that conforms to the law as long as they hire a physician consultant. NPs who want to prescribe but whose state laws require physician oversight can prescribe as long as a physician does whatever is necessary to conform to the state’s requirements. NPs, who cannot be designated as primary care providers (PCPs) and handle panels of managed care patients, actually perform the patient care, while a physician is designated as the PCP. The NPs say their reward is that the patients know that the NP is providing their care and appreciate the NP’s efforts.

Although many NPs are making the best of existing law, in many states, the law is far from satisfactory. The states where NPs are free to practice their profession without mandated participation from physicians are still the minority.

▪ Opportunities in a Changing Field

In states where barriers to NP practice have been lifted and where reimbursement is attainable from third-party payers, there are opportunities for healthcare delivery systems that increase attention to preventive medicine, increase access to citizens, and provide alternatives to expensive physician-oriented systems.

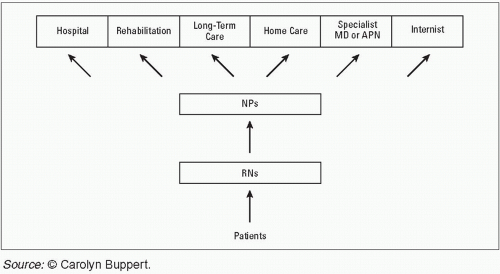

Under a see-a-nurse-first system, patients initially would be seen by a registered nurse or NP. The nurses would take care of as many of a patient’s healthcare problems as would be prudent, and would seek consultation and referral for those problems that exceeded the scope of their practice.

Figure 17-1 depicts a see-a-nurse-first system.

▪ Opponents of a See-a-Nurse-First System

Physicians can be counted on to oppose a see-a-nurse-first system of healthcare delivery. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has the following policy regarding NP practice: “The nurse practitioner should not function as an independent health practitioner. The AAFP position is that the nurse practitioner should only function in a collaborative practice arrangement under the direction and responsible supervision of a practicing, licensed physician.”1

Some patients may be suspicious of a see-a-nurse-first system. For that reason, patients should be offered a choice of nurse and/or physician providers. Once the law offers a level playing field, both physicians and NPs will have incentives to improve their services to patients and will thereby advance their respective professions.

▪ What Are the Challenges for NPs Attempting to Advance the Profession?

First, there is the matter of the energy required. NPs are accustomed to volunteer organizations. Now is the time to consider hiring professionals. Public relations experts, not volunteers, develop public relations campaigns for physician organizations. Physicians do not expect to see 30 patients at the office, stop by the hospital on the way home, and then get together at 8 pm to develop public relations campaigns. Physician organizations hire public relations firms or in-house staff whose sole job is to attend to the public image of physicians. NPs can hire professionals, too, and should. Much publicity can be gained with a small budget and creative public relations professionals.

Second, there is the challenge of publicizing the good in NPs and comparing NP services to physician services without denigrating physicians. The solution to that challenge is to continue to publicize the studies of the efficacy and quality of NPs that have shown that NPs are as competent providers of primary care as physicians.

Third, there is the phenomenon that every action generates a reaction. When physicians see NPs step up efforts to advance the profession, physicians may feel it necessary to react with more aggressive efforts. NPs who are intimidated by this thought should remember their goal and stay on course.

The major focus of physician arguments—that only physicians should have the authority to direct primary care—is the educational differential between NPs and physicians. The counterargument for NPs is: Physicians set their educational level. There has been no major study of physician education and training since 1910, when Abraham Flexner published a report commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation that called for medical training to be university-affiliated programs rather than 8-month programs where students came without a high school diploma.2 There are no studies showing that the appropriate education for providing primary care is 4 years of medical school and 3 years of residency, which is the education for all physicians, whether they are brain surgeons, researchers into neurotransmitters, or providers of primary care. On the contrary, there are many studies showing that NPs are quite appropriate providers of primary care (see Chapter 13).

▪ Strategies to Implement Collectively

NPs are familiar with the advantages of working collectively toward change. First, individuals can pool money to have more purchasing power than one individual NP. Second, groups are taken seriously by lawmakers and political parties.

Marshalling support of even homogeneous groups is no small accomplishment. In the case of NPs, a stumbling block to collective action is the heterogeneity of NPs, as not every NP has the same professional interests, the same viewpoint, or the same goals. For example, NPs who are professors have professional goals that include getting government funding for educational programs for NPs. NPs who are clinicians do not have educational funding as a top-priority goal. Instead, they have the goal of being able to practice with few barriers.

Nevertheless, organizations are necessary for the advancement of the NP profession. NPs inspire, encourage, and rejuvenate other NPs, all of which is necessary when the goals are long term.

▪ Ten Organizational Strategies

The following ten strategies are suggested for NPs who want to advance the profession and/or their own opportunities.

Set a Goal

For example, one NP set herself a goal of being a “primary care provider,” credentialed with health plans. She built up a base of loyal patients, became an excellent clinician, and worked with the state’s organization of NPs to change the law so that an NP could be designated by a health maintenance organization as a PCP. She succeeded. Of course, NPs work not only in primary care, but in specialty practices and tertiary care. In every setting, NPs need to choose an achievable and reasonable goal, one that would affect not only themselves, but other NPs.

Analyze the Law for Barriers

There is much ignorance and confusion about the law as it affects NPs. Some NPs say, “The law says we need to be supervised, but we really practice independently.” By participating in a practice situation where the law is stretched, NPs are taking a risk. In some states, the law puts responsibility squarely on the NP for ensuring that supervisory requirements are met. Clinics, hospitals, and medical groups have had little to lose by providing little or no supervision and letting the NP go as far as the NP’s willingness for intellectual adventure and professional judgment allows. NPs are bringing in at least $150 per hour and getting paid about $40 per hour. If an NP makes few mistakes and no one enforces the law, everything runs smoothly. However, the better an NP does with independent decision making, the more momentum builds for more independence, and pretty soon the NP is out on a limb, with no physician available to answer telephone calls to help, much less supervise. As soon as an NP makes a mistake, the burden is back on the NP for not seeking supervision. If the NP is a practice owner making $150 per hour and willing to take the risk, that is one thing, but if the NP is an employee earning $40 per hour, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Some NPs have argued that current law and custom permit NPs to practice in a satisfying manner, so “why open a can of worms” by attempting to change the law? This argument not only offends a sense of legal “neatness,” where law and current practice jibe, but condones a timidity that is incongruent with the level of assertion needed to perform as an NP. Why would NPs participate in life-and-death decisions for patients and yet retreat from challenging statutory omissions that relegate NPs to the invisible category of “others” or “nonphysicians”?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree