Stages of Shock

QUICK LOOK AT THE CHAPTER AHEAD

Shock is a syndrome of life-threatening hemodynamic imbalance leading to poor perfusion and an inadequate supply of oxygen and nutrients to the cells. Different classifications of shock exist, but the pathophysiology for all remains the same. In this chapter we define the different stages of shock and describe the clinical manifestations.

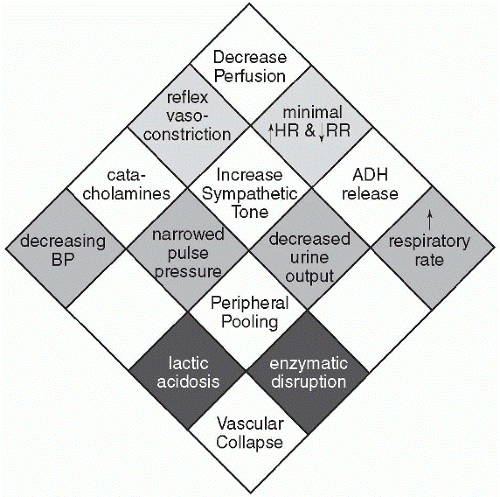

If detected early on shock can be reversed; however, as the shock state progresses the chances of reversing the chain of events become impossible and death ensues. There are three stages of shock (Figure 50-1). The first stage is compensation where changes can be made to reverse the process. Stage II is the progressive stage, indicating that perfusion disturbance has increased and may lead to the third stage, the refractory stage, or a condition that can no longer be reversed.

Stage I: Compensation

As stage I begins the body’s metabolic needs are still being met through adequate perfusion, but as the blood pressure decreases compensatory

mechanisms take over. Once the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is alerted to a decreasing blood pressure, peripheral vasoconstriction maintains blood flow to the major organs, particularly the brain and heart. A mild increase in heart rate helps to increase cardiac output, and dilation of the coronary arteries allows for an increased delivery of oxygen to the cardiac muscle.

mechanisms take over. Once the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is alerted to a decreasing blood pressure, peripheral vasoconstriction maintains blood flow to the major organs, particularly the brain and heart. A mild increase in heart rate helps to increase cardiac output, and dilation of the coronary arteries allows for an increased delivery of oxygen to the cardiac muscle.

Though compensatory mechanisms take over in the first stage of shock, keeping the major organs perfused comes at a cost to other systems.

Though compensatory mechanisms take over in the first stage of shock, keeping the major organs perfused comes at a cost to other systems.Keeping the major organs perfused comes at a cost to other systems. Blood flow to the kidneys is decreased, which activates the release of renin, which activates angiotensinogen to become angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor. Aldosterone is stimulated to increase sodium reabsorption, and the release of antidiuretic hormone increases water resorption. The hormones of the SNS, epinephrine and norepinephrine, also cause vasoconstriction to the blood vessels. All these mechanisms help to increase blood volume to the heart and vital organs, but blood flow to other body systems is diminished.

Capillary hydrostatic pressure becomes decreased and falls below the colloidal osmotic pressure. This allows fluid to flow from the interstitial to the intravascular space, helping to increase blood volume and pressure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree