Skin care

The skin is the body’s largest organ. Besides helping to shape a patient’s self-image, the skin performs many physiologic functions. For example, it protects internal body structures from the environment and potential pathogens. It also regulates body temperature and homeostasis and serves as an organ of sensation and excretion. Meticulous skin care is essential to overall health because intact, healthy skin is the body’s first line of defense. To ensure that a patient maintains healthy skin, you must make certain that all skin care measures prevent injury, control infection, promote skin growth, and control pain. Providing emotional support to a patient whose self-image may be affected by a skin disorder or injury is also an essential element to good nursing care.

To enhance natural healing, skin wounds need regular dressing changes (with extra changes for soiled dressings), thorough cleaning and, if necessary, debridement to remove debris, reduce bacterial growth, and encourage tissue repair.

To control pain, you’ll need to assess the patient’s pain and response to therapy. If he has minor pain or pruritus, a topical agent may be all that’s needed. For moderate pain, such techniques as positioning and bed rest may help. A patient in severe pain may require a strong opioid analgesic for pain relief.

A patient who has a disfiguring or painful skin disorder may suffer from frustration, depression, and anger. Along with physical support, the patient will require emotional support as he develops coping mechanisms to deal with his altered self-image.

If you’re working with a patient who has impaired skin integrity — for example, a patient with burns or pressure ulcers — your primary goal is to prevent or control infection because damage to skin integrity increases the risk of infection, which could delay healing, worsen pain, and possibly threaten the patient’s life. To provide the best care, it’s important that you’re aware of the current recommendations from such organizations as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ, the American Burn Association ABA, the American College of Surgeons Committee ACSC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, the Dermatology Nurses Association DNA, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations JCAHO, the Wound Healing Society WHS, and the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society WOCN. In this chapter, many practices are evidence-based EB. You’ll find additional practices that are grounded in basic principles of science SCIENCE and the American Hospital Association’s Patient Care Partnership PCP.

Arterial ulcer care

Arterial ulcers can result from arterial insufficiency caused by arterial vessel compression or obstruction or from trauma to an ischemic limb. Usually, these ulcers occur on the leg or foot. Consider your patient at risk for an arterial ulcer if he has these conditions: atherosclerosis (most common cause of arterial problems), absence of a lowerextremity pulses, claudication (muscle pain that occurs after exercise), or pain that occurs when the patient is resting, which is a symptom of severe arterial insufficiency.

Assessment of an arterial ulcer should include a comprehensive clinical history and specific information related to the history of the arterial ulcer. Patients with arterial ulcers are typically older; have peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia; and are smokers. Assess the intact skin surrounding the ulcer for temperature changes and capillary refill, which mostly likely will be longer than 3 seconds. Obtain ankle brachial indices (ABI; the ankle pressure divided by the brachial pressure) using Doppler blood pressure measurements. The test

compares blood pressure in the brachial artery to that in the ankle. Arterial insufficiency is likely to be present if the ABI is 0.9 or less. Severe ischemia is present when the ABI is less than 0.5. WOCN Transcutaneous oxygen measurements (TcPO2) can also be taken if the ulcer is not healing. A TcPO2 of less than 40 mm Hg indicates poor wound healing. WOCN

compares blood pressure in the brachial artery to that in the ankle. Arterial insufficiency is likely to be present if the ABI is 0.9 or less. Severe ischemia is present when the ABI is less than 0.5. WOCN Transcutaneous oxygen measurements (TcPO2) can also be taken if the ulcer is not healing. A TcPO2 of less than 40 mm Hg indicates poor wound healing. WOCN

When assessing the patient at risk for arterial insufficiency, be sure to inspect and palpate the skin for changes in color and temperature. Always compare one side of the body with the other, and apply the backs of both of your hands to the patient’s legs at the same time to ensure that the temperature difference is the patient’s and not your own. During palpation, be sure to assess all pulses in the lower extremities (femoral, dorsalis pedis, popliteal, and posterior tibial pulse). However, don’t be surprised if you aren’t able to feel the dorsalis pedis pulses, because some patients don’t have them even if their arterial system is normal. The popliteal pulse can be hard to palpate, but don’t skip this pulse even if you find the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial pulse and know that blood is getting to the foot.

Also, assess the patient’s level of pain. He may experience it in the form of intermittent claudication, resting pain, nocturnal pain, positional pain, or pain that hasn’t responded to analgesia.

Complete or partial arterial blockage may lead to tissue necrosis and ulceration. Signs and symptoms on the affected extremity include:

pulselessness

painful ulceration

small, punctate ulcers that are usually well circumscribed

cool or cold skin

pallor on elevation or dependent rubor

edema

pale or necrotic wound base

delayed capillary refill time (briefly push on the end of the toe and release; normal color should return to the toe in 3 seconds or less)

skin that’s shiny, thin, or dry

loss of hair.

Use noninvasive vascular tests, such as Doppler, ABI, and TcPO2 measurements, to aid in the diagnosis. Duplex scanning and arteriograms may also be performed, if indicated.

Treatment of an arterial ulcer has many goals, the primary one being to increase the circulation to the area in question. This can be done surgically or medically depending on the cause of the ulcer and the patient’s overall medical condition. Bypass grafting is the standard surgical treatment. Percutaneous angioplasty and the placement of stents are also done. Keeping the tissue base moist and free from infection and necrotic debris are also concerns. Frequent assessment of the wound base for signs and symptoms of infection is vital because signs can be subtle as a result of reduced blood flow.

Pain control, another goal of treatment, can be managed in the patient with intermittent claudication by encouraging him to walk to the point of near-maximal pain three times per week. This has been shown to increase pain-free walking and total distance. WOCN l-arginine taken orally for 2 weeks has also been shown to improve symptoms of intermittent claudication. WOCN The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN) has established guidelines for treating arterial ulcers.

Other suggested treatments include hyperbaric oxygen therapy, topical autologous activated mononuclear cells (which have been shown to benefit ischemic ulcers), and intermittent pneumatic compression, which may help patients with intermittent claudication.

Equipment

Bedside table • piston-type irrigating system • two pairs of gloves • normal saline solution, as ordered • sterile 4″ × 4″ gauze pads • sterile cotton swabs • selected topical dressing • linen-saver pads • impervious plastic trash bag • disposable wound-measuring device (a square, transparent card with concentric circles arranged in bull’s-eye fashion and bordered with a straightedge ruler)

Implementation

Confirm the patient’s identity using two patient identifiers according to facility policy. JCAHO

Wash your hands. CDC

Explain the procedure to the patient. PCP

If the patient has adequate circulation to heal an arterial ulcer, the objective is to keep the ulcer moist. Moist dressings should be applied only after vascular

supply is restored. Because of poor circulation, an arterial ulcer bed dries out fast; keeping the dressing moist will decrease the risk of tissue damage during dressing changes. WOCN

Irrigate the arterial ulcer with normal saline solution, and be sure to blot the surrounding skin dry.

Moisten the gauze dressing with saline solution.

Gently place the dressing over the surface of the ulcer. To separate surfaces within the wound, gently place a dressing between opposing wound surfaces. To avoid damage to tissues, don’t pack the gauze tightly.

Change the dressing often enough to keep the wound moist.

An occlusive dressing is contraindicated when peripheral pulses are absent. The typical choice for an arterial ulcer is a dressing that provides for frequent visualization and protects the surrounding skin. Choose a dressing that controls exudate, enhances autolytic debridement, and maintains a moist wound environment, which accelerates the healing process. Modern wound dressings haven’t been shown to have a significant impact on wound healing. EB

If debridement is going to be used to treat an arterial ulcer, it should occur only after vascular supply is restored. WOCN

Avoid chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma.

Seek out regular nail and foot care by a professional.

Wear proper-fitting shoes with socks or hose.

Avoid pressure on the toes and heels.

Stop smoking to slow progression of arteriosclerosis.WOCN

Increase calorie and protein intake.

Nursing diagnoses

Acute pain

Impaired tissue integrity

Expected outcomes

The patient will:

express pain relief

voice intent to stop smoking and manage dressing change routine

remain free from ulcers, color changes, and edema.

Complications

Infection, one of the most common complications of an ulcer, may cause foul-smelling drainage, persistent pain, severe erythema, induration, and elevated skin and body temperatures. Advancing infection or cellulitis can lead to septicemia. Severe erythema may signal worsening cellulitis, which indicates that the offending organisms have invaded the tissue and are no longer localized.

Documentation

Document the ulcer’s location; its length, width, and depth; and any tunneling of the wound (using centimeters). Record the appearance of the wound bed and the date and time the dressing was changed. If your facility allows, photograph the wound to supplement your documentation.

Supportive references

Bouza et al. “Efficacy of Modern Dressings in the Treatment of Leg Ulcers”, Wound Repair and Regeneration 13(3):218-29, May-June 2005. EB

Davis, J., and Gray, M. “Is the Unna’s Boot Bandage as Effective as a Four-Layer Wrap for Managing Venous Leg Ulcers?” Journal of Wound, Ostomy, & Continence Nursing 32(3):153-56, May-June 2005.

McMullin, G.M. “Improving the Treatment of Leg Ulcers”, Medical Journal of Australia 175(7):375-78, August 2001.

Sieggreen, M.Y., and Kline, R.A. “Arterial Insufficiency and Ulceration: Diagnosis and Treatment Options”, Nurse Practitioner 29(9):46-52, September 2004.

WOCN. Clinical Fact Sheet: Arterial Insufficiency. Glenview, Ill.: WOCN; 2004. www.wocn.org.

WOCN. Guideline for Management of Wounds in Patients with Lower-Extremity Arterial Disease. Glenview, Ill.: WOCN; June 2002.

Wipke-Tevis, D., and Sae-Sia, W. “Management of Vascular Leg Ulcers”, Advances in Skin & Wound Care 18(8):446-47, October 2005.

Zafar, A. “Management of Diabetic Foot — Two Years Experience”, Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad 13(1):14-16, January-March 2001.

Burn care

The goals of burn care are to maintain the patient’s physiologic stability, repair skin integrity, prevent infection, and promote maximal functioning and psychosocial

health. Competent care immediately after a burn occurs can dramatically improve the success of overall treatment. (See Burn care at the scene.)

health. Competent care immediately after a burn occurs can dramatically improve the success of overall treatment. (See Burn care at the scene.)

Burn care at the scene

By acting promptly when a burn injury occurs, you can improve the patient’s chance of uncomplicated recovery. Emergency care at the scene should include steps to stop the burn from worsening; assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs); a call for help from an emergency medical team; and emotional and physiologic support for the patient.

Stop the burning process

If the victim is on fire, tell him to fall to the ground and roll to put out the flames. (If he panics and runs, air will fuel the flames, worsening the burn and increasing the risk of inhalation injury.) Or, if you can, wrap the victim in a blanket or other large covering to smother the flames and protect the burned area from dirt. Keep his head outside the blanket so that he doesn’t breathe in toxic fumes. As soon as the flames are out, unwrap the patient so that the heat can dissipate.

Cool the burned area with any nonflammable liquid. This decreases pain and stops the burn from growing deeper or larger.

If possible, remove potential sources of heat, such as jewelry, belt buckles, and some types of clothing. In addition to adding to the burning process, these items may cause constriction as edema develops. If the patient’s clothing adheres to his skin, don’t try to remove it. Rather, cut around it.

Cover the wound with a tablecloth, sheet, or other smooth, nonfuzzy material.

Assess the damage

Call for help as quickly as possible. Send someone to contact the emergency medical service (EMS).

Assess the patient’s ABCs, and perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation, if necessary. Then check for other serious injuries, such as fractures, spinal cord injury, lacerations, blunt trauma, and head contusions.

Estimate the extent and depth of the burns. If flames caused the burns and the injury occurred in a closed space, assess for signs of inhalation injury: singed nasal hairs, burns on the face or mouth, soot-stained sputum, coughing or hoarseness, wheezing, or respiratory distress.

If the patient is conscious and alert, try to get a brief medical history as soon as possible.

Reassure the patient that help is on the way. Provide emotional support by staying with him, answering questions, and explaining what’s being done for him.

When help arrives, give the EMS a report on the patient’s status.

Every burn victim should be evaluated initially as a trauma patient after the systematic approach developed by the American College of Surgeons Committee. The primary survey focuses mainly on maintaining the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation. When the burn is caused by a chemical agent, the priority is to remove the offending agent and irrigate the affected area with water. The secondary survey focuses on a head-to-toe assessment, followed by efforts to stop the burn and contain the injury. Specific elements of the survey should include burn severity, which is determined by the depth and extent of the burn; determination of a possible inhalation injury; and other factors, such as age, complications, coexisting illnesses, and the possibility of abuse. (See Estimating burn surfaces. Also see Evaluating burn severity, page 516.)

According to the American Burn Association, you’ll need to carefully monitor your patient’s respiratory status, especially if he has suffered smoke inhalation. Be aware that a patient with burns involving more than 20% of his total body surface area usually needs fluid resuscitation, which aims to support the body’s compensatory mechanisms without overwhelming them. Expect to give fluids (such as lactated Ringer’s solution) to keep the patient’s urine output at 30 to 50 ml/hour, and expect to monitor blood pressure and heart rate. You’ll also need to control body temperature because skin loss interferes with temperature regulation. Use warm fluids, heat lamps, and hyperthermia blankets, as appropriate, to keep the patient’s temperature above 97° F (36.1° C), if possible. Additionally, you’ll frequently review laboratory values,

such as serum electrolyte levels, to detect early changes in the patient’s condition. ABA

such as serum electrolyte levels, to detect early changes in the patient’s condition. ABA

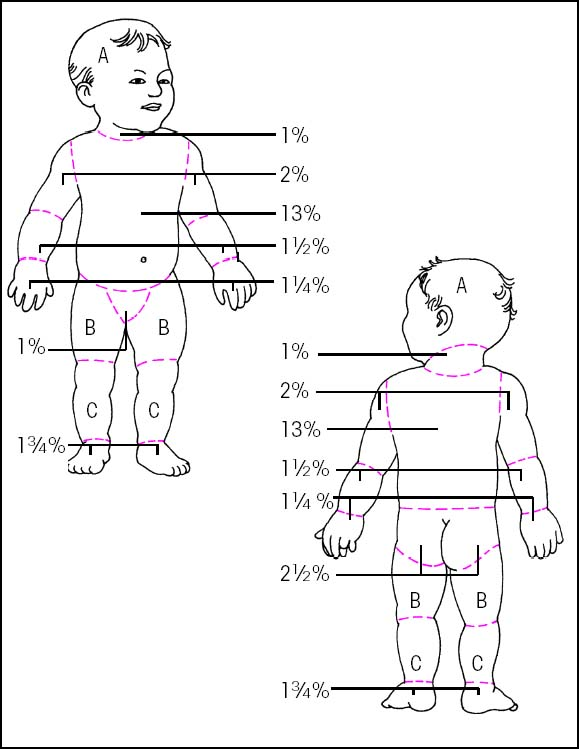

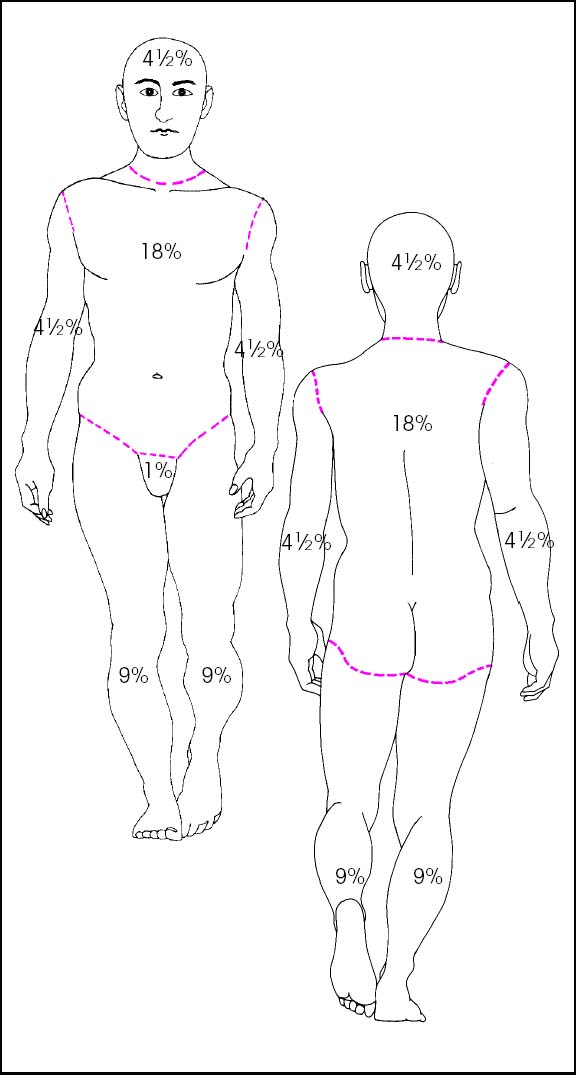

Estimating burn surfaces

Different methods are required to assess body surface area (BSA) in children and adults because the proportion of BSA changes as the body grows.

Rule of nines

The “rule of nines” quantifies BSA in percentages, either in fractions of nine or multiples of nine. To use this method, mentally assess the patient’s burns using the body chart shown below. Add the corresponding percentages for each body section burned. Use the total — a rough estimate of burn extent — to calculate initial fluid replacement needs.

|

Lund-Browder chart

The rule of nines isn’t accurate for infants and children because their body proportions differ from those of adults. An infant’s head, for example, accounts for about 17% of his total BSA, whereas an adult’s head comprises 7% of his BSA. The Lund-Browder chart, as shown below, is based on human anatomic studies relating the proportion of a specific body area to the body as a whole and can be used for infants, children, and adults

Evaluating burn severity

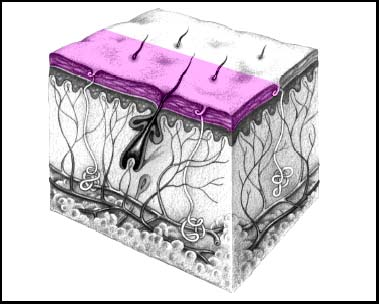

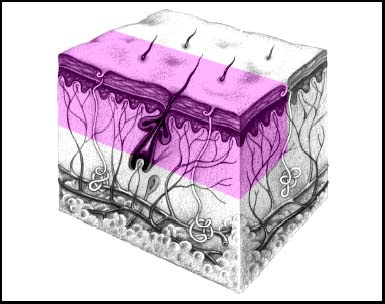

To judge a burn’s severity, assess its depth and extent, color, and other factors, as shown below.

Superficial partial-thickness (first-degree) burn

Does the burned area appear pink or red with minimal edema? Is the area sensitive to touch and temperature changes? If so, the patient most likely has a superficial partial-thickness — or first-degree — burn affecting only the epidermal skin layer.

|

Deep partial-thickness (second-degree) burn

Does the burned area appear pink or red, with a mottled appearance? Do red areas blanch when you touch them? Does the skin have large, thick-walled blisters with subcutaneous edema? Does touching the burn cause severe pain? Is the hair still present? If so, the person most likely has a deep partial-thickness — or second-degree — burn affecting the epidermal and dermal layers.

|

Full-thickness (third-degree) burn

Does the burned area appear red, waxy white, brown, or black? Does red skin remain red with no blanching when you touch it? Is the skin leathery with extensive subcutaneous edema? Is the skin insensitive to touch? Does the hair fall out easily? If so, the patient most likely has a full-thickness — or third-degree — burn that affects all skin layers.

|

Infection can increase wound depth, cause rejection of skin grafts, slow healing, worsen pain, prolong hospitalization, and even lead to death. To help prevent infection, use strict aseptic technique during care, dress the burn site as ordered, monitor and rotate I.V. lines regularly, and carefully assess the extent of the burn as well as body system function and the patient’s emotional status.

Early positioning after a burn is extremely important to prevent contractures. Careful positioning and regular exercise for burned extremities help maintain joint function and minimize deformity. When the extremities aren’t being exercised, they should be maintained in maximal extension, using splints if necessary. Particular attention should be focused on the hands and neck because they’re the most prone to rapid contracture. ABA (See Positioning the burn patient to prevent deformity.)

Skin integrity is repaired through aggressive wound debridement, followed by maintenance of a clean wound bed until the wound heals or is covered with a skin graft.

Early excision and debridement of the wound in the first 48 hours has been shown to decrease blood loss and reduce hospital stay; however, this procedure should be used only on wounds that are clearly full-thickness burns. ABA Surgery takes place as soon as possible after fluid resuscitation. Most wounds are managed with twice-daily dressing changes using a topical antibiotic. Burn dressings encourage healing by barring germ entry and by removing exudate, eschar, and other debris that host infection. After thorough wound cleaning, a topical antibacterial is applied and the wound is covered with absorptive, coarse mesh gauze. Roller gauze typically tops the dressing and is secured with elastic netting or tape.

Positioning the burn patient to prevent deformity

For each of the potential deformities listed below, you can use the corresponding positioning and interventions to help prevent the deformity.

| Burned area | Potential deformity | Preventive positioning | Nursing interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck |

|

|

|

| Axilla |

|

|

|

| Pectoral region |

|

|

|

| Chest or abdomen |

|

|

|

| Lateral trunk |

|

|

|

| Elbow |

|

|

|

| Wrist |

|

|

|

| Fingers |

|

|

|

| Hip |

|

|

|

| Knee |

|

|

|

| Ankle |

|

|

|

Equipment

Normal saline solution • bowl • blunt scissors • tissue forceps • ordered topical medication (for example, silver nitrate solution or silver sulfadiazine) • burn gauze • roller gauze • elastic netting or tape • fine-mesh gauze • elastic gauze • cotton-tipped applicators • ordered pain medication • three pairs of gloves • gown • mask • surgical cap • heat lamps • impervious plastic trash bag • cotton bath blanket • 4″ × 4″ gauze pads

A sterile field is required, so all equipment and supplies used to clean and dress the wound should be sterile.

Preparation of equipment

Warm the normal saline solution by immersing unopened bottles in warm water. Assemble equipment on the dressing table. Make sure the treatment area has adequate light to allow accurate wound assessment. Open equipment packages using sterile technique. Arrange supplies on a sterile field according to the order of use.

To prevent cross-contamination, plan to dress the cleanest areas first and the dirtiest or most contaminated areas last. To help prevent excessive pain or cross-contamination, you may need to dress the wounds in stages to avoid exposing all wounds at the same time.

Implementation

Confirm the patient’s identity using two patient identifiers according to facility policy. JCAHO

Administer the ordered pain medication about 20 minutes before beginning wound care to maximize patient comfort and cooperation.

Explain the procedure to the patient and provide privacy. PCP

Turn on overhead heat lamps to keep the patient warm. Make sure they don’t overheat the patient.

Pour the warmed normal saline solution into the sterile bowl in the sterile field.

Wash your hands. CDC

Removing a dressing without hydrotherapy

Put on a gown, a mask, and sterile gloves. CDC

Remove dressing layers down to the innermost layer by cutting the outer dressings with sterile blunt scissors. Lay open these dressings.

If the inner layer appears dry, soak it with warmed normal saline solution to ease removal.

Remove the inner dressing with sterile tissue forceps or your gloved hand.

Because soiled dressings harbor infectious microorganisms, dispose of the dressings carefully in the impervious plastic trash bag according to facility policy. Dispose of your gloves, and wash your hands. CDC

Put on a new pair of sterile gloves. Using gauze pads moistened with normal saline solution, gently remove exudate and old topical medication.

Carefully remove all loose eschar with sterile forceps and scissors, if ordered. (See “Mechanical debridement”, page 526.) ABA

Assess the wound’s condition. It should appear clean, with no debris, loose tissue, purulence, inflammation, or darkened margins.

Before applying a new dressing, remove your gown, gloves, and mask. Discard of them properly, and put on a clean gown, gloves, mask, and surgical cap. ABA CDC

Applying a wet dressing

Soak fine-mesh gauze and the elastic gauze dressing in a large, sterile basin containing the ordered topical medication (for example, silver nitrate solution). ABA

Wring out the fine-mesh gauze until it’s moist but not dripping, and apply it to the wound. Warn the patient that he may feel transient pain when you apply the dressing.

Wring out the elastic gauze dressing, and position it to hold the fine-mesh gauze in place.

Roll an elastic gauze dressing over the dressing to keep dressings intact.

Cover the patient with a cotton bath blanket to prevent chills. Change the blanket if it becomes damp. Use an overhead heat lamp, if necessary.

Change the dressings frequently, as ordered, to keep the wound moist, especially if you’re using silver nitrate. Silver nitrate becomes ineffective and the silver ions may damage tissue if the dressing becomes dry. (To maintain moisture, some protocols call for irrigating the dressing with solution at least every 4 hours through small slits cut into the outer dressing.) ABA

Applying a dry dressing with a topical medication

Remove old dressings, and clean the wound as described previously.

Apply a thin layer (2 to 4 mm thick) of the ordered medication to the wound with your gloved hand. Apply several layers of burn gauze over the wound to contain the medication but allow exudate to escape.

Remember to cut the dressing to fit only the wound areas; don’t cover unburned areas.

Cover the entire dressing with roller gauze, and secure it with elastic netting or tape.

Providing arm and leg care

Apply the dressings from the distal to the proximal area to stimulate circulation and prevent constriction. Wrap the burn gauze once around the arm or leg so the edges overlap slightly. Continue wrapping in this way until the gauze covers the wound. ABA SCIENCE

Apply dry roller gauze dressing to hold the bottom layers in place. Secure with elastic netting or tape.

Providing hand and foot care

Wrap each finger separately with a single layer of a 4″ × 4″ gauze pad to allow the patient to use his hands and to prevent webbing contractures.

Place the hand in a functional position, and secure this position using a dressing. Apply splints, if ordered. SCIENCE

Put gauze between each toe as appropriate, to prevent webbing contractures.

Providing chest, abdomen, and back care

Apply the ordered medication to the wound in a thin layer. Cover the entire burned area with sheets of burn gauze.

Wrap with roller gauze or apply a specialty vest dressing to hold the burn gauze in place.

Secure the dressing with elastic netting or tape. Make sure the dressing doesn’t restrict respiratory motion, especially in very young or elderly patients or in those with circumferential injuries.

Providing facial care

If the patient has scalp burns, clip or shave the hair around the burn, as ordered. Clip other hair until it’s about 2″ (5 cm) long to prevent contamination of burned scalp areas.

Shave facial hair if it comes in contact with burned areas. ABA

Typically, facial burns are managed with milder topical medications (such as triple antibiotic ointment) and are left open to air. If dressings are required, make sure they don’t cover the eyes, nostrils, or mouth.

Providing ear care

Clip or shave the hair around the affected ear.

Remove exudate and crusts with cotton-tipped applicators dipped in normal saline solution.

Place a layer of 4″ × 4″ gauze behind the auricle to prevent webbing.

Apply the ordered topical medication to 4″ × 4″ gauze pads, and place the pads over the burned area. Before securing the dressing with a roller bandage, position the patient’s ears normally to avoid damaging the auricular cartilage. ABA

Assess the patient’s hearing ability. ABA

Providing eye care

Clean the area around the eyes and eyelids with a cotton-tipped applicator and normal saline solution every 4 to 6 hours, or as needed, to remove crusts and drainage. ABA

Administer ordered eye ointment or eyedrops.

If the eyes can’t be closed, apply lubricating ointment or drops, as ordered. SCIENCE

Be sure to close the patient’s eyes before applying eye pads to prevent corneal abrasion. Don’t apply topical ointment near the eyes without a physician’s order.

Providing nasal care

Check the nostrils for inhalation injury, such as inflamed mucosa, singed vibrissae, and soot.

Clean the nostrils with cotton-tipped applicators dipped in normal saline solution. Remove crusts.

Apply the ordered ointment.

If the patient has a nasogastric tube, use tracheostomy ties to secure the tube. Be sure to check ties frequently for tightness resulting from facial tissue swelling. Clean the area around the tube every 4 to 6 hours. ABA

Special considerations

Thorough assessment and documentation of the wound’s appearance are essential to detect infection

and other complications. A purulent wound or green-gray exudate indicates infection, an overly dry wound suggests dehydration, and a wound with a swollen, red edge suggests cellulitis. Suspect a fungal infection if the wound is white and powdery. Healthy granulation tissue appears clean, pinkish, faintly shiny, and free from exudate.

Successful burn care after discharge

Wound care

Instruct the patient or a family member to follow this procedure when changing dressings:

Clean the bathtub, shower, or washbasin thoroughly, and then assemble the required equipment (topical medication, if ordered, and dressing supplies). Open the supplies aseptically on a clean surface.

Wash your hands. Remove the old dressing and discard it.

Using a clean washcloth and mild soap and water, wash the wound to remove all the old medication. Try to remove any loose skin as well. Pat the skin dry with a clean towel.

Check the burned area for signs of infection: redness, heat, foul odor, increased pain, and difficulty moving the area. If any of these signs is present, notify the physician after completing the dressing change.

Wash your hands. If ordered, apply a thin layer of topical medication to the burned area.

Cover the burned area with thin layers of gauze, and wrap it with a roller gauze. Finally, secure the dressing with tape or elastic netting.

Self-care

To enhance healing, instruct the patient to eat well-balanced meals with adequate carbohydrates and proteins, to eat between-meal snacks, and to include at least one protein source in each meal and snack. Tell him to avoid tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine because they constrict peripheral blood flow.

Advise the patient to wash new skin with mild soap and water. To prevent excessive skin dryness, instruct him to use a lubricating lotion and to avoid lotions containing alcohol or perfume. Caution the patient to avoid bumping or scratching regenerated skin tissue.

Recommend nonrestrictive, nonabrasive clothing, which should be laundered in a mild detergent. (New clothing should be washed before it’s worn.) Advise the patient to wear protective clothing during cold weather to prevent frostbite.

Warn the patient not to expose new skin to strong sunlight and to always use a sunblock with a sun protection factor of 20 or higher. Also, tell him not to expose new skin to irritants, such as paint, solvents, strong detergents, and antiperspirants. Recommend cool baths or ice packs to relieve itching.

To minimize scar formation, the patient may need to wear a pressure garment — usually for 23 hours a day for 6 months to 1 year. Instruct him to remove it only during daily hygiene. Advise him that the garment is too tight if it causes cold, numbness, or discoloration in the fingers or toes or if its seams and zippers leave deep, red impressions for more than 10 minutes after the garment is removed. If these signs or symptoms appear, he should consult his physician.

Blisters protect underlying tissue, so leave them intact unless they impede joint motion, become infected, or cause the patient discomfort.

Keep in mind that the patient with healing burns has increased nutritional needs. He’ll require extra protein and carbohydrates to accommodate an almost doubled basal metabolism.

If you must manage a burn with topical medications, exposure to air, and no dressing, you’ll need to watch for such problems as wound adherence to bed linens, poor drainage control, and partial loss of topical medications.

Provide encouragement and emotional support, and urge the patient to join a burn survivor support group. Teach the family or caregivers how to encourage, support, and provide care for the patient. (See Successful burn care after discharge.)

Nursing diagnoses

Acute pain

Impaired skin integrity

Expected outcomes

The patient will:

express pain relief

exhibit improved or healed wounds

not develop complications, such as infection or deformities.

Complications

Infection is the most common burn complication. Others include disfigurement, pain, and emotional issues.

Documentation

Record the date and time of all care provided. Describe the wound’s condition, special dressing-change techniques, topical medications administered, positioning of the burned area, and the patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

Supportive references

ABA. Practice Guidelines for Burn Care. Supplement to Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation 22(3 Suppl), May-June 2001.

McCallon, S.K., and Browing, K. “Treatment of Partial Thickness Burns Using Balsam Peru, Castor Oil, Trypsin Ointment: A Case Study: 607”, Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing 32(3S)(Suppl 2):S5, May-June 2005.

Mendez-Eastman, S. “Burn Injuries”, Plastic Surgical Nursing 25(3):133-39, July-September 2005.

Diabetic ulcer care

Diabetic foot ulcers are usually caused by peripheral neuropathy, both sensory (lack of sensation) and motor (decreased function of the motor nerves in the foot), but they may also result from peripheral vascular disease. Arterial insufficiency can be another cause of a nonhealing ulcer in a patient with diabetes. An ulcer can also result from trauma or excess pressure undetected by the patient because of neuropathy. The border is undefined and may be small at the surface, although the wound may have a large subcutaneous abscess. Drainage usually is absent unless the ulcer is infected.

To assess the diabetic foot ulcer start by taking a complete history, which could help you to determine the patient’s knowledge about the disease and see whether he’s complying with his treatment regimen. Assess the patient’s feet for ulcers on the plantar aspect of the toes, laterally to the foot, between the toes, and on the tips of the toes. Be sure to look at the surrounding intact skin for erythema, induration, and maceration. Assess the footwear usually worn by the patient. Does it protect the feet or does it promote rubbing that could lead to skin breakdown? Assess the wound for granulation tissue, necrotic tissue, anatomic structures, color of the wound bed and exudate, and odor. (See Tailoring wound care to wound color, page 522.)

Toe brachial index or ankle brachial index, taken with a Doppler and a specially sized pneumatic cuff, provide an objective indicator of arterial blood flow to the lower extremity.

Diabetic neuropathic ulcers should be treated like pressure ulcers, with debridement of necrotic tissue, moist wound healing, and off-loading of pressure.

Equipment

Bedside table • piston-type irrigating system • two pairs of gloves • normal saline solution, as ordered • sterile 4″ × 4″ gauze pads • sterile cotton swabs • selected topical dressing • linen-saver pads • impervious plastic trash bag • disposable wound-measuring device (a square, transparent card with concentric circles arranged in bull’s-eye fashion and bordered with a straightedge ruler)

Preparation of equipment

Assemble equipment at the patient’s bedside. Cut the tape into strips for securing the dressings. Loosen the lids on cleaning solutions and medications for easy removal. Loosen existing dressing edges and tape before putting on gloves. Attach an impervious plastic trash bag to the bedside table to hold used dressings and other refuse.

Implementation

Confirm the patient’s identity using two patient identifiers according to facility policy. JCAHO

Explain the procedure to the patient. PCP

Premedicate the patient, as needed, before changing the dressing.

Tailoring wound care to wound color

With any wound, promote healing by keeping it moist, clean, and free from debris. If your patient has an open wound, you can assess how well it’s healing by inspecting its color, and then use wound color to guide the specific management approach.

Red wounds

Red, the color of healthy granulation tissue, indicates normal healing. When a wound begins to heal, a layer of pale pink granulation tissue covers the wound bed. As this layer thickens, it becomes beefy red. Cover a red wound, keep it moist and clean, and protect it from trauma. Use a transparent dressing, a hydrocolloidal dressing, or a gauze dressing moistened with sterile normal saline solution or impregnated with petroleum jelly or an antibiotic.

Yellow wounds

Yellow is the color of exudate produced by microorganisms in an open wound. When a wound heals without complications, the immune system removes microorganisms. But if there are too many microorganisms to remove, exudate accumulates and becomes visible. Exudate usually appears whitish yellow, creamy yellow, yellowish green, or beige. Water content influences the shade — dry exudate appears darker.

If your patient has a yellow wound, clean it and remove the exudate, using high-pressure irrigation, and then cover it with a moist dressing. Use absorptive products or a moist gauze dressing with or without an antibiotic. You may also use hydrotherapy with whirlpool or high-pressure irrigation.

Black wounds

Black, the least healthy color, signals necrosis. Dead, avascular tissue slows healing and provides a site for microorganisms to proliferate.

Black wounds should be debrided. After the dead tissue is removed, apply a dressing to keep the wound moist and guard against external contamination. As ordered, use enzyme products, surgical debridement, hydrotherapy with whirlpool or high-pressure irrigation, or a moist gauze dressing.

Multicolored wounds

You may note two or even all three colors in a wound. In this case, you would classify the wound according to the least healthy color present. For example, if your patient’s wound is both red and yellow, classify it as a yellow wound.

Wash your hands, and put on sterile gloves. Be sure to review your facility’s policy on standard precautions. CDC

Remove the existing dressing, and place it into the impervious trash bag. (If the dressing is dry, soak it with saline before removing it so that granulating tissue isn’t removed when the dressing is pulled off.) CDC

Inspect the wound. Note the location, pain, shape, size of the wound, wound base and edges, periwound skin and the color, amount, and odor of drainage or necrotic debris. Measure the wound perimeter with the disposable wound-measuring device.

Irrigate the wound, using a piston-style syringe containing normal saline solution.

Remove and discard your soiled gloves, wash your hands, and put on a pair of sterile gloves.

Insert a cotton-tipped swab into the wound to assess for tunneling. Gauge the tunnel depth by how far you can insert your finger or cotton swab.

Clean the ulcer with normal saline solution or a commercially prepared noncytotoxic cleanser. When applying the gauze, use a moist dressing to promote a moist wound environment. WOCN

To apply a moist dressing, squeeze out the excess saline from the gauze layers. Place the layer of moist gauze into the wound. If there’s tunneling, make sure the dressing is tucked loosely into the tunneled areas. Make sure that the moist dressing touches all the tissue in the wound, filling up all of the wound’s dead space. Avoid overpacking the wound. (See “Pressure ulcer care”, page 527, for more detailed instructions.) Your patient may need absorbent dressings if the ulcer has moderate to heavy drainage.

Notify the practitioner of your assessment findings. The patient may need ulcer debridement or surgical intervention. Debridement helps ulcer healing by removing necrotic tissue that acts as a physical barrier to wound repair. If the ulcer is caused by arterial insufficiency, the patient may need surgery. WOCN

If the patient’s wound is infected, prepare him for a tissue biopsy — the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis of infection — and the possible need for a systemic antibiotic. WOCN

Check the patient’s laboratory test results, and notify the physician of any findings that fall outside the reference range.

Prepare the patient for tests that may be performed to determine ulcer severity and the presence of complications. Radiographic imaging is used to help rule out gas formation, the presence of foreign objects, and bony abnormalities. Magnetic resonance imaging is used to help diagnose osteomyelitis. A transcutaneous oxygen tension measurement determines skin perfusion. If the ulcer is in an atypical location or doesn’t respond to treatment, a biopsy may be performed.

Apply growth factors, as ordered, after necrotic tissue and infection have been eliminated and perfusion to the wound is adequate. WOCN

Assess the patient’s level of pain, and refer him to a pain specialist if necessary.

Instruct the patient to keep his legs elevated above the level of his heart while sitting or sleeping. Suggest that he place phone books in between his mattress and box spring so that his legs are elevated above his head.

Nursing diagnoses

Deficient knowledge (procedure)

Impaired skin integrity

Expected outcomes

The patient will:

explain his skin care regimen

verbalize an understanding of those behaviors he should follow to avoid complications

exhibit improved or healed wounds.

Complications

Gangrene is a common complication of diabetic ulcers, especially those that occur on the feet. In many cases, amputation is necessary to control the spread of infection.

Documentation

Document the ulcer’s anatomic location and its length, width, and depth. Record the extent of tunneling or undermining, if present. Reassess the wound at specified intervals, and document the date and time of dressing changes. If the wound is infected, its dimensions may change rapidly. Also document any ulcer-related pain, asking the patient if he feels pain, teaching him to use a pain-rating scale, and looking for nonverbal indicators. Photograph the wound to supplement your comprehensive wound care documentation.

Supportive references

Brooks, B., et al. “TBI or not TBI: That is the Question. Is it Better to Measure Toe Pressure than Ankle Pressure in Diabetic Patients?” Diabetic Medicine 18(7):528-32, July 2001.

McMullin, G.M. “Improving the Treatment of Leg Ulcers”, Medical Journal of Australia 175(7):375-78, August 2001.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access