Scope of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) Nursing Practice

Nurses who specialize in intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are unique in the population that they serve. Because the history of this nursing specialty was primarily institutional until the late 1950s, and because of the stigma attached to this population, many nurses have not become familiar with this area. In fact, this nursing specialty was only recognized as such by the American Nurses Association in 1997 (Nehring, 1999). Unlike many nursing specialties, the scope of practice for nurses who specialize in IDD extends across all levels of care and all health care and many educational settings. Even though healthcare consumers with IDD are present today in all communities and health care settings, they remain a vulnerable population. This is because they often require assistance to advocate for their needs and many health care professionals are not educated and skilled to care for their specific condition and developmental needs. Such health disparities were highlighted in the Surgeon General’s report, Closing the Gap: A National Blueprint for Improving the Health of Persons with Mental Retardation (U.S. Public Health Service, 2002). Working in an interdisciplinary context, nurses continue to strive to promote the importance of the discipline of nursing in this specialty field and to provide specific health care at both the generalist and advanced practice level.

Definition of Nursing

Nursing’s Social Policy Statement: The Essence of the Profession (ANA, 2010b, p. 3) builds on previous work and provides the following contemporary definition of nursing:

Nursing is the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families/legal guardians, communities, and populations.

This definition serves as the foundation for the following expanded description of the Scope of Nursing Practice and the Standards of Professional Nursing Practice for nurses who specialize in intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Definition of Intellectual and Developmental Disability (IDD)

Intellectual and developmental disability is a broad term that refers to a wide variety of mental and/or physical conditions that interfere with an individual’s ability to function effectively at an expected developmental level. These conditions have been referred to as developmental disabilities or mental retardation in the past. Today, intellectual and developmental disability is the term used to describe these conditions. An intellectual and developmental disability is:

A disability characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior, which covers many everyday social and practical skills. This disability originates before the age of 18 (Schalock, Borthwick-Duffy, Bradley, Buntinx, Coulter, Craig, et al., 2010).

Nurses who specialize in the care of persons of all ages with IDD care for persons with these conditions. These conditions may be organic and nonorganic or social in nature.

It is important to clarify that IDD is different from chronic conditions or illness and disabilities in general. Chronic can simply mean any condition that exists over a period of time. Although IDD exists across time, the definition

is more specific. This is also true for disabilities, a general term that refers to any condition that limits activities of daily living. Again, IDD may limit activities of daily living, but the conditions require understanding of more specific information regarding physiology, epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, genetics, diagnosis, treatment and management, follow-up, and nursing implications. The care of healthcare consumers with IDD most often requires the coordinated efforts of an interprofessional team.

is more specific. This is also true for disabilities, a general term that refers to any condition that limits activities of daily living. Again, IDD may limit activities of daily living, but the conditions require understanding of more specific information regarding physiology, epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, genetics, diagnosis, treatment and management, follow-up, and nursing implications. The care of healthcare consumers with IDD most often requires the coordinated efforts of an interprofessional team.

Another term often used is children with special health care needs. Children with IDD often have special health care needs, but this may not be true of all members of this population. For example, a child with Down syndrome may have special needs, but these special needs may not always concern the child’s health at any given time.

As new terminology comes into use, it is important to identify and describe particular conditions (e.g., pervasive developmental disabilities and special needs child), so that nurses do not lose sight of the knowledge and skills needed to care for persons with IDD, regardless of the diagnosis. Although the terms used to describe IDD may overlap (e.g., developmental disabilities and special health care needs in the child with cerebral palsy), the definition of intellectual and developmental disabilities is used in federal legislation and must be understood by nurses.

History of Nursing in IDD

The history of nursing in IDD is unique. This section gives a short summary of the education of nurses and nursing care in this specialty.

Early education for nurses who specialized in the care of persons, of any age, with IDD occurred both in general nursing hospital schools and in asylums and institutions. Until the early 20th century, persons with IDD were diagnosed as having mental illness, and their care took place in settings where persons with all forms of mental illness were housed. It was not until after WWI, when a better understanding of mental illness occurred, that the care of persons with IDD was more specifically detailed. Terminology at this time included idiot and imbecile. In the early 1960s, President Kennedy brought needed attention to the living conditions of persons of all ages with IDD, then called mental retardation. New legislation was introduced and for the first time funding became available for this population. Large institutional settings remained the primary place of residence for persons of all ages with IDD

until the late 1960s. It was the social norm to place newborns and children with known conditions resulting in IDD in institutions as soon as possible so as not to burden the families, either financially or through social stigma.

until the late 1960s. It was the social norm to place newborns and children with known conditions resulting in IDD in institutions as soon as possible so as not to burden the families, either financially or through social stigma.

After public attention to the custodial and often inhumane care of persons with IDD in the early 1970s, radical changes took place. Many individuals with IDD were moved back to their homes and to newly formed community settings, such as group homes, semi-independent living arrangements (SILAs), and smaller congregate settings (e.g., 16 beds). The transition from institutional to community living varies state by state. Today, newborns with IDD are no longer placed in institutional settings. Most individuals with IDD live with their families in the community. Others live in small-group community settings; only the most severely affected individuals who require substantial medical care remain in larger developmental centers (Nehring, 1999).

Nursing care has also evolved throughout history. Early documentation about nursing care was written either by physicians or nurses who cared for both persons with IDD and mental illness. Specific literature on the nursing care of persons with IDD written by nurses first appeared with any frequency in the 1950s. At that time, nurses in institutional settings did little more than record vital signs and occasional patient weights and give medications. Public health nurses also provided care for children with IDD who remained at home. However, parents were often encouraged to enroll their children in institutions by the time they reached school age. The first national meeting for nurses specializing in the care of children with IDD was sponsored by the Children’s Bureau in 1958 (Nehring, 1999).

In the 1960s, nursing care in the institution resembled the nursing care provided in hospitals. The role of the nurse expanded to include education and research. Advanced practice registered nurses were employed by some institutions and postbaccalaureate and graduate programs emerged to provide education designed especially for the care of children and adolescents with IDD. Interdisciplinary faculty (including nurses) at university-affiliated programs and facilities (UAPs or UAFs), established by President Kennedy in universities across the country, offered interdisciplinary education to future specialists in this field (including nurses), conducted research on topics related to mental retardation, and provided health and social services to individuals with IDD and their families.

Nurses began to write more prolifically about the care of children with IDD conditions; the increased numbers of articles and books; some of which are now considered classics, were especially useful for public health nurses. Developmental diagnostic clinics were established across the country to identify and refer children for developmental and health care when appropriate. Nursing consultants who specialized in this field were hired by the Children’s Bureau; Division of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, U.S. Public Health Service; Mental Retardation Division, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Association of Retarded Children; and the United Cerebral Palsy Associations, Inc. National meetings were convened for these nursing specialists and the first standards of nursing practice for this specialty emerged in 1968, The Guidelines for Nursing Standards in Residential Centers for the Mentally Retarded (Haynes, 1968; Nehring, 1999).

The 1970s saw the first education legislation mandating that all children with IDD receive a free and appropriate public education from the ages of 3 through 21 years. Advanced practice roles for nurses in this specialty continued to expand, including roles in schools and early intervention programs for the infant from birth to three years of age. Publications and regular national and regional meetings continued to be held throughout this decade. Special courses in this area also began to appear in nursing programs across the country (Nehring, 1999).

The term developmental disabilities was first introduced during the Nixon presidency to describe conditions similar to those defined as mental retardation but that differed slightly. Interdisciplinary care was the norm in the 1980s, when all disciplines worked together with the individual with IDD and his or her family members in assessing and planning the care of the person with IDD in a variety of settings (Nehring, 1999). In 1980, the American Nurses Association published School Nurses Working with Handicapped Children (Igoe, Green, Heim, Licata, MacDonough, & McHugh, 1980). Later in the 1980s, two sets of standards of nursing practice for nurses specializing in this field emerged: Standards of Nursing Practice in Mental Retardation/Developmental Disabilities (Aggen & Moore, 1984) and Standards for the Clinical Advanced Practice Registered Nurse in Developmental Disabilities/Handicapping Conditions (Austin, Challela, Huber, Sciarillo, & Stade, 1987).

Emphasis on the adult with IDD emerged in the nursing literature in the 1990s. An examination of the individual with IDD across the lifespan was first highlighted in A Life-Span Approach to Nursing Care for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities (Roth & Morse, 1994). Nursing standards for this field were also revised: Standards of Developmental Disabilities Nursing Practice (Aggen, DeGennaro, Fox, Hahn, Logan, & VonFumetti, 1995) and Statement on the Scope and Standards for the Nurse Who Specializes in Developmental Disabilities and/or Mental Retardation (Nursing Division of the American Association on Mental Retardation and American Nurses Association, 1998). Other related standards of nursing practice in early intervention (ANA Consensus Committee, 1993), care of children and adolescents with special health and developmental needs (ANA Consensus Committee, 1994), and genetics (ISONG & ANA, 1998) were issued as well.

In the first years of the 21st century, a greater effort was made to provide educational materials for nursing students and nurses in practice who care for persons of all ages with IDD. Both the Nursing Division of the American Association on Mental Retardation and the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association have been developing separate, but complementary, projects to create a core curriculum for nurses and other health professionals (Nehring, 2005) and Internet materials, respectively.

This specialty field of nursing has changed greatly from its early years. As the healthcare system continues to evolve, so will the nursing care of persons of all ages with IDD. Such care continues to occur in a variety of settings and at both the professional registered nurse and advanced practice registered nurse levels. Continued publication and research into such nursing care are needed, as are additional didactic and clinical content materials for nursing students.

Professional Nursing’s Scope and Standards of IDD Nursing Practice

For more than a decade, nurse members of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) have deemed it important that there be a scope and standards of practice for this specialty. This document serves as the contemporary template for the practice of nursing in IDD, and the standards of practice portion of this document serves as a description of the practice of nurses who specialize in this field.

Description of the Scope of IDD Nursing Practice

The scope of practice statement describes the who, what, where, when, why, and how of nursing practice. Each of these questions must be answered to provide a complete picture of the dynamic and complex practice of IDD nursing and its evolving boundaries and membership. The full spectrum of the nurse’s role in this specialty is described for both the general and advanced practice registered nurse. The depth and breadth with which individual registered nurses engage in the total scope of nursing practice for this specialty depend on each nurse’s education, experience, role, and the population served.

Development and Function of IDD Nursing Standards

The Standards of Professional Nursing Practice in IDD Nursing are authoritative statements of the duties that all registered nurses in this specialty are expected to perform competently. The standards published herein may serve as evidence of the standard of care for this specialty, with the understanding that application of the standards depends on context. The standards are subject to change with the dynamics of this nursing specialty, as new patterns of professional practice are developed and accepted by the nursing profession and the public. In addition, specific conditions and clinical circumstances may also affect the application of these standards at a given time, such as during a natural disaster. The standards are subject to formal, periodic review and revision.

The Function of Competencies in IDD Nursing Standards

The competencies that accompany each standard may be evidence of compliance with the corresponding standard. The list of competencies is not exhaustive. Whether a particular standard or competency applies depends on the circumstances.

The Nursing Process in IDD Nursing

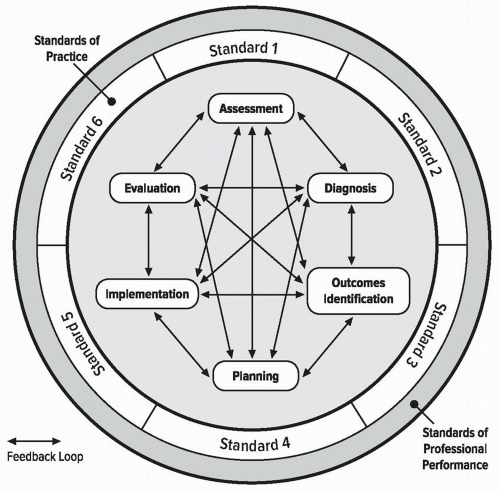

The nursing process is often conceptualized as the integration of singular actions of assessment, diagnosis, and identification of outcomes, planning, implementation, and finally, evaluation. The nursing process in practice is not

linear, as often conceptualized, with a single feedback loop from evaluation to assessment. Rather, it relies heavily on bidirectional feedback loops from each component, as illustrated in Figure 1. There is no deviation in this process for nurses specializing in IDD.

linear, as often conceptualized, with a single feedback loop from evaluation to assessment. Rather, it relies heavily on bidirectional feedback loops from each component, as illustrated in Figure 1. There is no deviation in this process for nurses specializing in IDD.

The Standards of Practice for IDD Nurses coincide with the steps of the nursing process, to represent the directive nature of the standards as the IDD professional nurse completes each component of the nursing process. Similarly, the Standards of Professional Performance for IDD Nurses relate to how the IDD professional nurse adheres to the Standards of Practice for IDD Nurses, completes the nursing process, and addresses other nursing practice issues and concerns (ANA, 2010a). Five tenets characterize contemporary nursing practice, and these are described here for the IDD nurse.

FIGURE 1. The Nursing Process and Standards of Professional Nursing Practice (ANA, 2010a) |

Tenets Characteristic of IDD Nursing Practice

1. IDD nursing practice is individualized.

IDD nursing practice respects diversity and is individualized to meet the unique needs of the healthcare consumer with IDD or situation. The healthcare consumer with IDD is defined to be the patient, person, client, family/legal guardians, group, community, or population with IDD who is the focus of attention and to whom the IDD registered nurse is providing services as sanctioned by the state regulatory bodies.

2. IDD nurses coordinate care by establishing partnerships.

The IDD registered nurse establishes partnerships with persons with IDD, families/legal guardians, support systems, and other providers, and uses in-person and electronic communications to reach a shared goal of delivering health care. Health care is defined as the attempt “to address the health needs of the patient and the public” (ANA, 2001, p.10). Collaborative interprofessional team planning is based on recognition of each discipline’s value and contributions, mutual trust, respect, open discussion, and shared decision-making.

3. Caring is central to the practice of the IDD registered nurse.

IDD professional nursing promotes healing and health in a way that builds a relationship between the IDD nurse and the healthcare consumer with IDD (Watson, 1999, 2008). “Caring is a conscious judgment that manifests itself in concrete acts, interpersonally, verbally, and nonverbally” (Gallagher-Lepak & Kubsch, 2009, p. 171). While caring for healthcare consumers with IDD, families/legal guardians, and populations is the key focus of IDD nursing, the IDD nurse additionally promotes self-care as well as care of the environment and society (Hagerty, Lynch-Sauer, Patusky, & Bouwseman, 1993).

4. IDD registered nurses use the nursing process to plan and provide individualized care to their healthcare consumers with IDD.

IDD nurses use theoretical and evidence-based knowledge of human experiences and responses to collaborate with healthcare consumers with IDD to assess, diagnose, identify outcomes, plan, implement, and evaluate care. IDD nursing interventions are intended to produce beneficial effects, contribute to quality outcomes, and—above all—do no harm. IDD nurses evaluate the effectiveness of their care in relation to identified outcomes and use evidence-based practice to improve care (ANA, 2010a). Critical thinking underlies each step of the nursing process, problem-solving, and decision-making. The nursing process is cyclical and dynamic, interpersonal and collaborative, and universally applicable.

5. A strong link exists between the professional work environment and the IDD registered nurse’s ability to provide quality health care and achieve optimal outcomes.

IDD professional nurses have an ethical obligation to maintain and improve healthcare practice environments conducive to the provision of quality health care (ANA, 2010b). Extensive studies have demonstrated the relationship between effective nursing practice and the presence of a healthy work environment (e.g., Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, & Cheney, 2008; Kelly, McHugh, & Aiken, 2011; Papastavrou et al., 2011). Mounting evidence demonstrates that negative, demoralizing, and unsafe conditions in the workplace (unhealthy work environments) contribute to medical errors, ineffective delivery of care, and conflict and stress among health professionals. IDD nurses are similarly affected.

Healthy Work Environments for IDD Nursing Practice

ANA supports the following models of healthy work environment design. These concepts apply to the healthy work environments of IDD nursing practice as well.

American Association of Critical Care Nurses

The American Association of Critical Care Nurses has identified six standards for establishing and maintaining healthy work environments (AACN, 2005):

Skilled Communication Nurses must be as proficient in communication skills as they are in clinical skills.

True Collaboration Nurses must be relentless in pursuing and fostering a sense of team and partnership across all disciplines.

Effective Decision-Making Nurses are seen as valued and committed partners in making policy, directing and evaluating clinical care, and leading organizational operations.

Appropriate Staffing Staffing must ensure the effective match between healthcare consumer needs and nurse competencies.

Meaningful Recognition Nurses must be recognized and must recognize others for the value each brings to the work of the organization.

Authentic Leadership Nurse leaders must fully embrace the imperative of a healthy work environment, authentically live it, and engage others in achieving it.

Magnet Recognition Program®

The Magnet Recognition Program® addresses the professional work environment, requiring that Magnet®-designated facilities adhere to the following model components [American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), 2008]:

Transformational Leadership The transformational leader leads people where they need to be in order to meet the demands of the future.

Structural Empowerment Structures and processes developed by influential leadership provide an innovative practice environment in which strong professional practice flourishes and the mission, vision, and values come to life to achieve the outcomes believed to be important for the organization.

Exemplary Professional Practice This demonstrates what professional nursing practice can achieve.

New Knowledge, Innovation, and Improvements Organizations have an ethical and professional responsibility to contribute to healthcare delivery, the organization, and the profession.

Empirical Quality Results Organizations are in a unique position to become pioneers of the future and to demonstrate solutions to numerous problems inherent in today’s healthcare systems. Beyond the “what” and “how,” organizations must ask themselves what difference these efforts have made.

Institute of Medicine

The Institute of Medicine has also reported that safety and quality problems occur when dedicated health professionals work in systems that neither support them nor prepare them to achieve optimal patient care outcomes (IOM, 2004). Such rapid changes as reimbursement modification and cost-containment efforts, new healthcare technologies, and changes in the healthcare workforce have influenced the work and work environment of nurses. Accordingly, concentration on key aspects of the work environment of IDD nursing practice—people, physical surroundings, and tools—can enhance healthcare working conditions and improve patient safety. These include:

Transformational leadership and evidence-based management

Maximizing workforce capability

Creating and sustaining a culture of safety and research

Workspace design and redesign to prevent and mitigate errors

Effective use of telecommunications and biomedical device interoperability

Model of Professional Nursing Practice Regulation

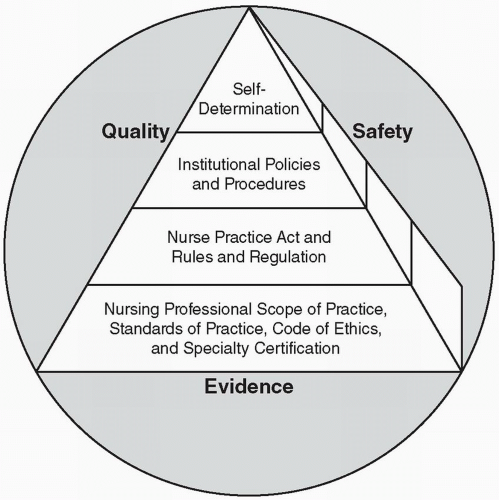

In 2006, the Model of Professional Nursing Practice Regulation (see Figure 2) emerged from ANA work and informed the discussions of specialty nursing and advanced practice registered nurse practice. This Model of

Professional Nursing Practice Regulation applies equally to IDD specialty nursing practice.

Professional Nursing Practice Regulation applies equally to IDD specialty nursing practice.

The lowest level in the model represents the responsibility of the IDD professional and specialty nursing organizations to their members and the public to define the scope and standards of practice for IDD nursing.

The next level up the pyramid represents the regulation provided by the nurse practice acts, rules, and regulations in the pertinent licensing jurisdictions. Institutional policies and procedures provide further considerations in the regulation of nursing practice for the IDD registered nurse and IDD advanced practice registered nurse.

Note that the highest level is that of self-determination by the IDD nurse, after consideration of all the other levels of input about professional

nursing practice regulation. The outcome is safe, quality, and evidence-based practice.

nursing practice regulation. The outcome is safe, quality, and evidence-based practice.

FIGURE 2. Model of Professional Nursing Practice Regulation (Styles, Schumann, Bickford, & White, 2008) |

Standards of Professional Nursing Practice in IDD

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree