Respiratory care

Diseases

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), also called shock lung or adult respiratory distress syndrome, results from increased permeability of the alveolocapillary membrane. Fluid accumulates in the lung interstitium, alveolar spaces, and small airways, causing the lung to stiffen. Effective ventilation is thus impaired, prohibiting adequate oxygenation of pulmonary capillary blood. Severe ARDS can cause intractable and fatal hypoxemia. However, patients who recover may have little or no permanent lung damage.

ARDS results from a variety of respiratory and nonrespiratory insults, such as:

aspiration of gastric contents

massive blood transfusions

drug overdose (barbiturates, glutethimide, or opioids)

gestational hypertension

hydrocarbon and paraquat ingestion

increased intracranial pressure

microemboli (fat or air emboli or disseminated intravascular coagulation)

near drowning

oxygen toxicity

pancreatitis, uremia, or miliary tuberculosis (rare)

prolonged heart bypass surgery

radiation therapy

sepsis (primarily gram-negative)

shock

smoke or chemical inhalation (nitrous oxide, chlorine, or ammonia)

trauma

viral, bacterial, or fungal pneumonia

leukemia

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

What happens in ARDS

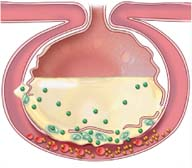

What happens in ARDSShock, sepsis, and trauma are the most common causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Trauma-related factors, such as fat emboli, pulmonary contusions, and multiple transfusions, may increase the likelihood that microemboli will develop.

Phase 1

In phase 1, injury reduces normal blood flow to the lungs. Platelets aggregate and release histamine (H), serotonin (S), and bradykinin (B).

|

Phase 2

In phase 2, those substances—especially histamine—inflame and damage the alveolocapillary membrane, increasing capillary permeability. Fluids then shift into the interstitial space.

|

Phase 3

In phase 3, as capillary permeability increases, proteins and fluids leak out, increasing interstitial osmotic pressure and causing pulmonary edema.

|

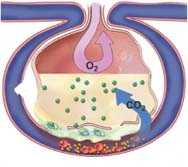

Phase 4

In phase 4, decreased blood flow and fluids in the alveoli damage surfactant and impair the cell’s ability to produce more. As a result, alveoli collapse, impeding gas exchange and decreasing lung compliance.

|

Phase 5

In phase 5, sufficient oxygen (O2) can’t cross the alveolocapillary membrane, but carbon dioxide (CO2) can and is lost with every exhalation. O2 and CO2 levels decrease in the blood.

|

Signs and symptoms

Apprehension

Crackles

Dyspnea

Hypoxemia

Intercostal and suprasternal retractions

Cough

Confusion

Hypotension

Mental sluggishness

Motor dysfunction

Rapid, shallow breathing

Restlessness

Rhonchi

Tachycardia

Treatment

Correction of the underlying cause

Prevention of progression and the potentially fatal complications of hypoxemia and respiratory acidosis

Administration of humidified oxygen with continuous positive airway pressure

Possibly ventilatory support with intubation, volume ventilation, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

Fluid restriction

Diuretics

Correction of electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities

Treatment to reverse severe metabolic acidosis with sodium bicarbonate may be necessary, although in severe cases, this may worsen the acidosis if carbon dioxide can’t be cleared adequately

Administration of fluids and vasopressors to maintain blood pressure

Antibiotic administration

Administration of prostaglandins

Nursing considerations

Frequently assess the patient’s respiratory status.

Check for clear, frothy sputum, which may indicate pulmonary edema.

Maintain a patent airway.

Closely monitor heart rate and blood pressure. Watch for arrhythmias that may result from hypoxemia, acid-base disturbances, or electrolyte imbalance.

Monitor serum electrolytes and correct imbalances.

Measure intake and output; weigh the patient daily.

Check ventilator settings frequently.

Monitor arterial blood gas studies and pulse oximetry.

Give sedatives, as needed, to reduce restlessness.

If the patient is receiving PEEP, check for hypotension, tachycardia, and decreased urine output.

Give tube feedings and parenteral nutrition, as ordered.

Perform passive range-of-motion exercises or help the patient perform active exercises, if possible, to help maintain joint mobility.

Provide meticulous skin care to prevent skin breakdown.

Plan patient care to allow periods of adequate rest.

Provide emotional support.

Place in prone position to improve chest wall compliance and drainage of bronchial secretions.

Teaching about ARDS

Teaching about ARDS

Explain the disorder to the patient and his family. Tell them which signs and symptoms may occur, and review necessary treatment.

Orient the patient and his family to the unit and health care facility surroundings. Explain equipment needed to provide adequate oxygenation.

Tell a recuperating patient that recovery takes time and that he’ll feel weak for a while. Urge him to share his concerns with the staff.

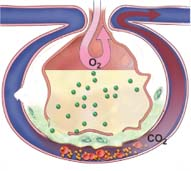

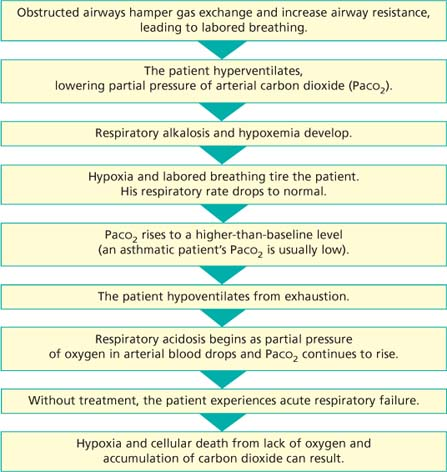

Asthma

Asthma is a reversible lung disease characterized by obstruction or narrowing of the airways, which are typically inflamed and hyperresponsive to a variety of stimuli. It may resolve spontaneously or with treatment. Its symptoms range from mild wheezing and dyspnea to life-threatening respiratory failure. Symptoms of bronchial airway obstruction may persist between acute episodes.

Signs and symptoms

Chest tightness

Coughing with thick, clear, or yellow mucus

Cyanosis (late sign)

Diaphoresis

Nasal flaring

Pursed-lip breathing

Sudden dyspnea

Tachycardia

Tachypnea

Use of accessory muscles for breathing

Wheezing accompanied by coarse rhonchi

Determining asthma’s severity

Current guidelines for classifying asthma severity for patients age 12 and older are listed here.

Intermittent

Attacks no more than twice per week

Nighttime attacks no more than twice per month

Rescue inhaler used no more than twice per week

Asthma doesn’t interfere with daily activities

Normal FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second)

Mild persistent

Attacks more than twice per week but not every day

Nighttime attacks three to four nights per month

Rescue inhaler used more than 2 days per week

Asthma minorly interferes with daily activities

FEV1 greater than 80% of normal lung function most of the time

Moderate persistent

Daily attacks

Nighttime attacks more than once per week

Rescue inhaler used daily

Asthma moderately interferes with daily activities

FEV1 greater than 60% but less than 80%

Severe persistent

Continual, severe daily attacks

nighttime attacks daily

Rescue inhaler used multiple times per day

Asthma severely interferes with daily activities

FEV1 less than 60%

Treatment

Identification and avoidance of precipitating factors

Desensitization to specific antigens

Low-flow humidified oxygen

Inhaled steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (Azmacort)

Leukotriene inhibitors such as montelukast (Singulair)

Long-acting bronchodilators such as formoterol (Foradil Aerolizer)

Mast cell stabilizers, such as cromolyn sodium (Intal) or nedocromil (Alocril)

Aminophyllin (Truphylline) or theophylline (Slo-bid)

Short-acting bronchodilators, such as albuterol (Proventil) or levalbuterol (Xopenex)

Oral or I.V. corticosteroids

Mechanical ventilation

Nebulized atropine

Omalizumab (Xolair)

Bronchial thermoplasty

Nursing considerations

Administer the prescribed treatments and assess the patient’s response.

Place the patient in high Fowler’s position.

Monitor the patient’s vital signs, especially respiratory status.

Administer prescribed humidified oxygen.

Anticipate intubation and mechanical ventilation if the patient fails to maintain adequate oxygenation.

Monitor serum theophylline levels.

Observe for signs and symptoms of theophylline toxicity (vomiting, diarrhea, and headache).

Perform postural drainage and chest percussion.

Provide emotional support.

Anticipate the need for bronchoscopy or bronchial lavage when a lobe or larger area collapses.

Review arterial blood gas levels, pulmonary function test results, and SaO2 readings.

Teaching about asthma

Teaching about asthma

Teach the patient to avoid known allergens and irritants.

Describe prescribed drugs, including their names, dosages, actions, adverse effects, and special instructions.

Teach the patient how to use a metered-dose inhaler.

If the patient has moderate to severe asthma, explain how to use a peak flowmeter and to keep a record of peak flow readings.

Tell the patient to seek immediate medical attention if he develops a fever above 100º F (37.8º C), chest pain, shortness of breath without coughing or exercising, or uncontrollable coughing.

Teach diaphragmatic and pursed-lip breathing and effective coughing techniques.

Urge the patient to drink at least 3 qt (3 L) of fluids daily to help loosen secretions and maintain hydration.

Explain the importance of seeking immediate medical attention if the peak flow drops suddenly.

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a generalized dysfunction of the exocrine glands that affects multiple organ systems. Transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait, it’s the most common fatal genetic disease in white children. Affecting about 30,000 U.S. children and adults, cystic fibrosis is most common in Whites (1 in 3,300 births) and less common in Blacks (1 in 15,300 births), Native Americans, and Asians. It occurs equally in both sexes.

Most cases of cystic fibrosis arise from a mutation that affects the genetic coding for a single amino acid, resulting in a protein that doesn’t function properly. The abnormal protein resembles other transmembrane transport proteins. It lacks phenylalanine (an essential amino acid) that’s usually produced by normal genes. This abnormal protein may interfere with chloride transport by preventing adenosine triphosphate from binding to the protein and interfering with activation by protein kinase. The lack of essential amino acids leads to dehydration and mucosal thickening in the respiratory and intestinal tracts.

Signs and symptoms

Excessive salty taste to skin

Barrel chest

Clubbing of fingers and toes

Crackles and wheezing

Cyanosis

Dyspnea

Failure to thrive, poor weight gain, distended abdomen

Frequent bouts of pneumonia

Frequent bulky and foul-smelling stools (steatorrhea)

Frequent upper respiratory tract infections

Intestinal obstruction (meconium ileus in infants)

Persistent cough

Thick secretions

Treatment

Diet with increased fat and sodium

Salt supplements

Pancreatic enzyme replacement

Breathing exercises, chest percussion, and postural drainage

Inhaled beta-adrenergics

Broad-spectrum antimicrobials

Sodium channel blockers

Heart or lung transplant

Dornase alfa (Pulmozyme)

High-frequency chest compression vest

Oxygen therapy as needed

Bronchodilators

Mucolytic aerosols

Corticosteroids

Nursing considerations

Give medications as ordered. Administer pancreatic enzymes with meals and snacks.

Perform chest physiotherapy, including postural drainage and chest percussion several times per day.

Administer oxygen therapy as ordered. Check levels of arterial oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry.

Provide a well-balanced, high-calorie, high-protein diet. Include plenty of fats.

Administer vitamin A, D, E, and K supplements, if laboratory analysis indicates deficiencies.

Make sure the patient receives plenty of liquids to prevent dehydration, especially in warm weather.

Provide exercise and activity periods.

Encourage deep-breathing exercises.

Provide the young child with play periods and enlist the help of physical and play therapists.

Provide emotional support to the patient and parents. Encourage them to discuss their fears and concerns and answer questions as honestly as possible.

Include the family in all phases of patient care.

Teaching about cystic fibrosis

Teaching about cystic fibrosis

Tell the patient and his family about the disease and thoroughly explain all treatments. Make sure they know about tests to determine whether family members carry the cystic fibrosis gene.

Explain aerosol therapy, including intermittent nebulizer treatments before postural drainage. Tell the patient and his family that these treatments help loosen secretions and dilate bronchi.

Instruct family members in proper methods of chest physiotherapy.

Teach the patient and his family signs of infection and sudden changes they should report to the physician, including increased coughing, decreased appetite, sputum that thickens or contains blood, shortness of breath, and chest pain.

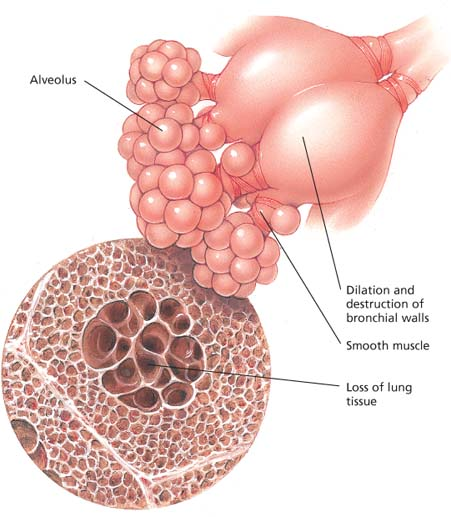

Emphysema

Emphysema is a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease characterized by the abnormal, permanent enlargement of the acini accompanied by destruction of alveolar walls without fibrosis. Obstruction results from tissue changes rather than mucus production, which occurs in asthma and chronic bronchitis. The distinguishing characteristic of emphysema is airflow limitation caused by thick elastic recoil in the lungs.

Senile emphysema results from degenerative changes that cause stretching without destruction of the smooth muscle. Connective tissue usually isn’t affected.

Signs and symptoms

Accessory muscle use for breathing

Anorexia with resultant weight loss

Barrel chest

Chronic cough with or without sputum production

Clubbed fingers and toes

Crackles and wheezing on inspiration

Decreased breath sounds

Decreased chest expansion

Decreased tactile fremitus

Dyspnea on exertion

Hyperresonance

Malaise

Mental status changes, if carbon dioxide retention worsens

Prolonged expiration and grunting

Tachypnea

Treatment

Avoidance of tobacco smoke and air pollution

Bronchodilators, such as beta-adrenergic blockers and albuterol (Proventil), aminophylline

Antibiotics

Flu vaccine to prevent influenza

Pneumovax to prevent pneumococcal pneumonia

Adequate hydration

Chest physiotherapy

Oxygen therapy

Mucolytics

Aerosolized or systemic corticosteroids

Lung volume reduction surgery

Lung transplantation

Nursing considerations

Provide incentive spirometry and encourage deep breathing.

Administer oxygen.

Give antibiotics as ordered.

Perform chest physiotherapy including postural drainage and chest percussion as ordered.

Make sure that the patient receives adequate hydration.

Provide high-calorie, protein-rich foods to promote health and healing.

Offer small, frequent meals to conserve energy.

Alternate rest and activity periods.

Teaching about emphysema

Teaching about emphysema

Explain the disease process and its treatments.

Urge the patient to avoid inhaled irritants, such as cigarette smoke, automobile exhaust fumes, aerosol sprays, and industrial pollutants.

Advise the patient to avoid crowds and people with infections and to obtain pneumonia and annual flu vaccines.

Warn the patient that exposure to blasts of cold air may trigger bronchospasm; suggest that he avoid cold, windy weather and that he cover his mouth and nose with a scarf or mask if he must go outside in such conditions.

Explain all drugs, including their indications, dosages, adverse effects, and special considerations.

Inform the patient about signs and symptoms that suggest ruptured alveolar blebs and bullae, and urge him to seek immediate medical attention if they occur.

Demonstrate how to use a metered-dose inhaler.

Teach the safe use of home oxygen therapy.

Teach the patient and his family how to perform postural drainage and chest physiotherapy.

Discuss the importance of drinking plenty of fluids to liquefy secretions.

For family members of a patient with familial emphysema, recommend a blood test for alpha1-antitrypsin. If a deficiency is found, stress the importance of not smoking and avoiding areas (if possible) where smoking is permitted.

Promote smoking cessation, if appropriate.

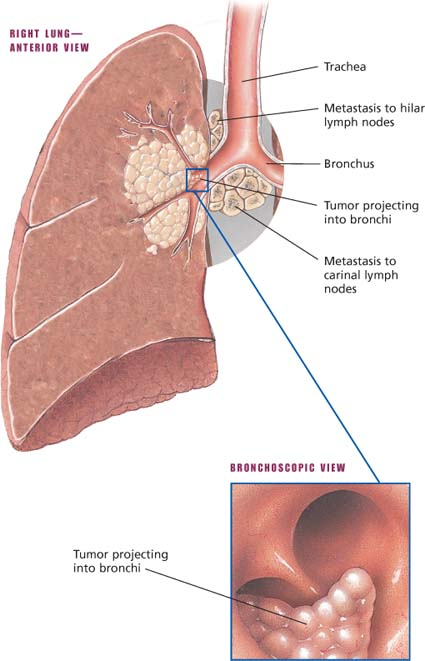

Lung cancer

Even though it’s largely preventable, lung cancer has long been the most common cause of cancer death in men and is an increasing cause of cancer death in women. Lung cancer usually develops within the wall or epithelium of the bronchial tree. The most common type is non-small-cell cancer, which includes epidermoid (squamous cell) carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell (anaplastic) carcinoma. Less common is small-cell lung cancer. prognosis varies with the extent of metastasis at the time of diagnosis and the cell type growth rate.

Signs and symptoms

Cough, hoarseness, wheezing, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain

Bone and joint pain

Clubbing of fingers

Cushing’s syndrome

Fever, weight loss, weakness, and anorexia

Hemoptysis, atelectasis, pneumonitis, and dyspnea

Hypercalcemia

Jugular vein distention and facial, neck, and chest edema

Piercing chest pain, increasing dyspnea, and severe arm pain

Pleural friction rub

Rust-colored or purulent sputum

Shoulder pain and unilateral paralysis of diaphragm

Wheezing

Treatment

Lobectomy, wedge resection, or pneumonectomy

Video-assisted chest surgery

Laser surgery

Radiation

Chemotherapy

Cisplastin and p53 gene therapy

Staging lung cancer

Using the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification system, the American Joint Committee on Cancer stages lung cancer as follows.

Primary tumor

TX—primary tumor can’t be assessed, or malignant tumor cells are detected in sputum or bronchial washings but undetected by X-ray or bronchoscopy

T0—no evidence of primary tumor

Tis—carcinoma in situ

T1—tumor 3 cm or less in greatest dimension, surrounded by normal lung or visceral pleura; no bronchoscopic evidence of cancer closer to the center of the body than the lobar bronchus

T1a—tumor 2 cm or less

T1b—tumor greater than 2 cm but less than or equal to 3 cm

T2—tumor larger than 3 cm but less than or equal to 7 cm; one that involves the main bronchus and is 2 cm or more from the carina; one that invades the visceral pleura; or one that’s accompanied by atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis that extends to the hilar region but doesn’t involve the entire lung

T2a—tumor greater than 3 cm but less than or equal to 5 cm

T2b—tumor greater than 5 cm but less than or equal to 7 cm

T3—tumor greater than 7 cm or of any size that extends into neighboring structures, such as the chest wall, diaphragm, or mediastinal pleura; tumor in the main bronchus that doesn’t involve but is less than 2 cm from the carina; or tumor that’s accompanied by atelectasis or obstructive pneumonitis of the entire lung

T4—tumor of any size that invades the mediastinum, heart, great vessels, trachea, esophagus, vertebral body, or carina; or tumor with malignant pleural effusion

Regional lymph nodes

NX—regional lymph nodes can’t be assessed

N0—no detectable metastasis to lymph nodes

N1—metastasis to the ipsilateral peribronchial or hilar lymph nodes or both

N2—metastasis to the ipsilateral mediastinal or subcarinal lymph nodes or both

N3—metastasis to the contralateral mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes, the ipsilateral or contralateral scalene lymph nodes, or the supraclavicular lymph nodes

Distant metastasis

M0—no evidence of distant metastasis

M1—distant metastasis

M1a—tumor with malignant pleural or pericardial effusion or pleural nodules; separate tumor nodules in contralateral lobe

M1b—metastasis in extrathoracic organs

Staging categories

Lung cancer progresses from mild to severe as follows:

Occult carcinoma—TX, N0, M0

Stage 0—Tis, N0, M0

Stage Ia—T1, N0, M0

Stage Ib—T2, N0, M0

Stage IIa—T1, N, M0

Stage IIb—T2, N1, M0; T3, N0, M0

Stage IIIa—T1, N2, M0; T2, N2, M0; T3, N1, M0; T3, N2, M0

Stage IIIb—any T, N3, M0; T4, any N, M0

Stage IV—any T, any N, M1

Nursing considerations

Give comprehensive, supportive care and provide patient teaching to minimize complications and speed the patient’s recovery from surgery,

radiation, and chemotherapy.

Urge the patient to voice his concerns and schedule time to answer his questions. Be sure to explain procedures before performing them.

After thoracic surgery

Maintain a patent airway and monitor chest tubes.

Check vital signs and watch for and report abnormal respirations and other changes.

Suction the patient as needed and encourage him to begin deep breathing and coughing as soon as possible. Check secretions often. Initially sputum will appear thick and dark with blood, but it should become thinner and grayish-yellow within 1 day.

Monitor and document amount and color of closed chest drainage. Keep chest tubes patent and draining effectively. Watch for fluctuation in the water seal chamber on inspiration and expiration, indicating that the chest tube remains patent. Watch for air leaks and report them immediately. Position the patient on the surgical side to promote drainage and lung reexpansion.

Monitor intake and output and maintain hydration.

Encourage early ambulation.

Teaching about lung cancer

Teaching about lung cancer

Preoperatively, teach the patient about postoperative procedures and equipment. Teach him how to cough and breathe deeply from the diaphragm and how to perform range-of-motion exercises. Reassure him that analgesics and proper positioning will help to control postoperative pain.

If the patient will have chemotherapy or radiation therapy, make sure he understands the adverse effects that occur and measures to prevent or reduce their severity.

To help prevent lung cancer, teach high-risk patients to stop smoking. Refer smokers who want to quit to

the local branch of the American Cancer Society or American Lung Association. Explain that nicotine gum or a nicotine patch and an antidepressant may be prescribed in combination with educational and support groups.

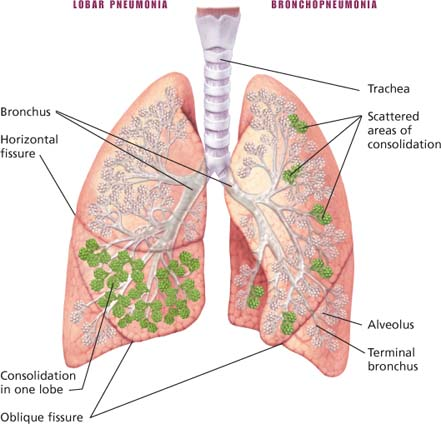

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an acute infection of the lung parenchyma that commonly impairs gas exchange. The prognosis is generally good for people who have normal lungs and adequate host defenses before the onset of pneumonia; however, pneumonia is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States.

Pneumonia can be classified by microbiologic etiology, location, or type.

Microbiologic etiology—Pneumonia can be viral, bacterial, fungal, protozoan, mycobacterial, mycoplasmal, or rickettsial in origin.

Location—Bronchopneumonia involves distal airways and alveoli; lobular pneumonia, part of a lobe; and lobar pneumonia, an entire lobe.

Type—Pneumonia may be described by the setting in which it was acquired. Community-acquired pneumonia is the most common type and occurs outside the health care setting. Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAC) occurs in the health care setting. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is a type of HAC occurring in ventilator patients. Health care–associated pneumonia occurs in other health care settings, such as nursing homes. Aspiration pneumonia refers to pneumonia that results from a foreign substance, such as emesis, entering the lungs.

Predisposing factors for bacterial and viral pneumonia include:

abdominal and thoracic surgery

aspiration

atelectasis

cancer (particularly lung cancer)

chronic illness and debilitation

common colds or other viral respiratory infections

exposure to noxious gases

immunosuppressive therapy

influenza

malnutrition

smoking

tracheostomy.

Predisposing factors for aspiration pneumonia include:

artificial airway use

debilitation

decreased level of consciousness

impaired gag reflex

nasogastric (NG) tube feedings

advanced age

poor oral hygiene

positioning during and after eating or feeding.

Signs and symptoms

Coughing

Crackles and decreased breath sounds

Dyspnea

Fatigue

Fever

Headache

Pleuritic chest pain

Rapid, shallow breathing

Shaking chills

Shortness of breath

Sputum production

Sweating

Decreased pulse oximetry reading

Distinguishing sources of pneumonia

The characteristics and prognosis of different types of pneumonia vary.

| Type | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Viral | |

| Influenza |

|

| Adenovirus |

|

| Respiratory syncytial virus |

|

| Measles (rubeola) |

|

| Chickenpox (varicella pneumonia) |

|

| Cytomegalo-virus |

|

| Bacterial | |

| Strepto-coccus | |

| |

| Klebsiella |

|

| Staphylo-coccus |

|

| Aspiration | |

| Aspiration of gastric or oropharyn-geal contents into trachea and lungs |

|

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy that varies with the causative agent (should be reevaluated early in the course of treatment)

Humidified oxygen therapy for hypoxemia

Mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure

High-calorie diet and adequate fluid intake

Bed rest

Analgesics to relieve pleuritic chest pain

Positive end-expiratory pressure to facilitate adequate oxygenation for patients with severe pneumonia who are on mechanical ventilation

Administration of bronchodilators

Administration of corticosteroids

Nursing considerations

Maintain a patent airway and adequate oxygenation. Monitor pulse oximetry. Measure arterial blood gas levels and administer supplemental oxygen as indicated.

Teach the patient how to cough and perform deep-breathing exercises.

If the patient requires endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, provide thorough respiratory care. Suction the patient as needed, using sterile technique.

Obtain sputum specimens as ordered.

Administer antibiotics as ordered and pain medication as needed; record the patient’s response to medications.

Administer I.V. fluids and electrolyte replacement therapy as ordered.

Maintain adequate nutrition and ask the dietary department to provide a high-calorie, high-protein diet consisting of soft, easy-to-eat foods.

Provide a quiet, calm environment for the patient, with frequent rest periods.

Provide emotional support, especially if respiratory failure occurs.

Teaching about pneumonia

Teaching about pneumonia

Explain the disease process and the treatment plan.

Teach the patient how to cough and perform deep-breathing exercises to clear secretions; encourage him to do so often.

Give emotional support by explaining all procedures (especially intubation and suctioning) to the patient and his family.

To control the spread of infection, tell the patient to sneeze and cough into a disposable tissue; tape a lined bag to the side of the bed for used tissues.

Teach the patient strategies to prevent pneumonia:

Advise against using antibiotics indiscriminately during minor viral infections because doing so may encourage upper airway colonization by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Encourage pneumonia and annual flu vaccination for high-risk patients, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart disease, or sickle cell disease.

Urge all bedridden and postoperative patients to perform deep-breathing and coughing exercises often. Tell caregivers to reposition such patients frequently to promote full aeration and drainage of secretions. Encourage early ambulation in postoperative patients.

Urge patients to avoid irritants that stimulate secretions, such as cigarette smoke, dust, and environmental pollution.

Pulmonary edema

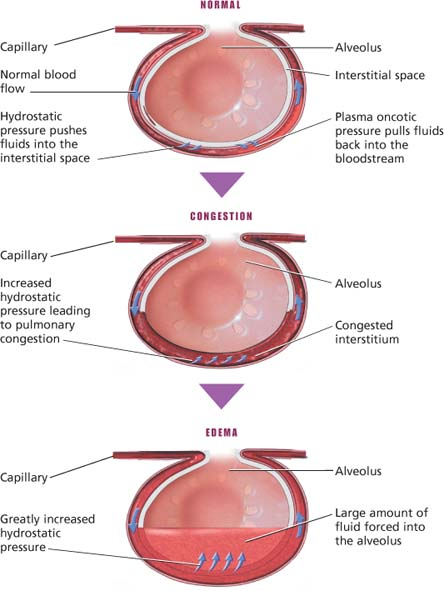

Pulmonary edema is the accumulation of fluid in the extravascular spaces of the lung. With cardiogenic pulmonary edema, fluid accumulation results from elevations in pulmonary venous and capillary hydrostatic pressures. A common complication of cardiac disorders, pulmonary edema can occur as a chronic condition or it can develop quickly and cause death.

Pulmonary edema usually results from left-sided heart failure due to arteriosclerotic, hypertensive, cardiomyopathic, or valvular heart disease. With such disorders, the compromised left ventricle can’t maintain adequate cardiac output; increased pressures are transmitted to the left atrium, pulmonary veins, and pulmonary capillary bed. This increased pulmonary capillary hydrostatic force promotes transudation of intravascular fluids into the pulmonary interstitium, decreasing lung compliance and interfering with gas exchange.

Signs and symptoms

Cold, clammy, and sweaty skin

Cough

Decreased level of consciousness

Dependent crackles or wheezing

Diastolic (S3) gallop

Dyspnea on exertion

Frothy, bloody sputum

Hypoxemia

Jugular vein distention

Orthopnea

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

Restlessness and anxiety

Tachycardia

Tachypnea

Thready pulse

Treatment

High concentrations of oxygen by cannula, face mask and, if necessary, assisted ventilation

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, inotropic drugs such as digoxin (Lanoxin), antiarrhythmic agents, beta-adrenergic blockers, and human B-type natriuretic peptide to treat heart failure

Vasodilator drugs, such as nitroprusside (Nipride) to reduce preload and afterload in acute episodes of pulmonary edema

Morphine to reduce anxiety and dyspnea as well as to dilate the systemic venous bed, promoting blood flow from pulmonary circulation to the periphery

Nursing considerations

Administer oxygen, as ordered, and monitor pulse oximetry.

Monitor vital signs every 15 to 30 minutes while giving nitroprusside in dextrose 5% in water by I.V. drip.

Watch for arrhythmias in patients receiving cardiac glycosides and diuretics and for marked respiratory depression in those receiving morphine.

Assess the patient’s condition frequently, and record response to treatment. Monitor arterial blood gas levels, electrolytes, oral and I.V. fluid intake, urine output and, in the patient with a pulmonary artery catheter, pulmonary end-diastolic and wedge pressures. Check cardiac monitor often. Report changes immediately.

Reassure the patient, who will have anxiety due to hypoxia and respiratory distress. Explain all procedures. Provide emotional support to his family as well.

Place the patient in high Fowler’s position to enhance lung expansion.

Teaching about pulmonary edema

Teaching about pulmonary edema

Explain all procedures to the patient and his family.

Review all prescribed drugs with the patient. If he takes digoxin (Lanoxin), show him how to monitor his own pulse rate and warn him to report signs of toxicity.

Encourage the patient to eat potassium-rich foods to lower the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

If the patient takes a vasodilator, teach him the signs of hypotension and emphasize the need to avoid alcohol.

Urge the patient to comply with the prescribed drug regimen to avoid future episodes of pulmonary edema.

Emphasize the need to report early signs of fluid overload.

Discuss ways to conserve physical energy.

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism is an obstruction of the pulmonary arterial bed that occurs when a mass—such as a dislodged thrombus—lodges in a pulmonary artery branch, partially or completely obstructing it. This causes a ventilation-perfusion mismatch, resulting in hypoxemia, as well as intrapulmonary shunting.

The prognosis varies. Although the pulmonary infarction that results from embolism may be so mild that the patient is asymptomatic, massive embolism (more than 50% obstruction of pulmonary arterial circulation) and infarction can cause rapid death.

In most patients, pulmonary embolism results from a dislodged thrombus (blood clot) that originates in the leg veins. More than one-half of such thrombi arise in the deep veins of the legs; usually multiple thrombi arise. Other, less common sources of thrombi include the pelvic, renal, and hepatic veins, the right side of the heart, and the upper extremities.

Signs and symptoms

Cyanosis

Dyspnea or unexplained shortness of breath

Hypotension

Jugular vein distention

Low-grade fever

Pleuritic pain or chest pain

Productive cough (sputum may be blood tinged)

Tachycardia or arrhythmia

Treatment

Oxygen therapy

Fibrinolytic therapy

Anticoagulation with heparin

Embolectomy

Vasopressors and antibiotics

Vena caval ligation, plication, or insertion of a device to filter blood returning to the heart and lungs to prevent future pulmonary emboli

Understanding thrombus formation

Thrombus formation results from vascular wall damage, venous stasis, and hypercoagulability of the blood. Trauma, clot dissolution, intravascular pressure changes, or a change in peripheral blood flow can cause the thrombus to loosen or become fragmented. Then, the thrombus—now called an embolus—floats to the heart’s right side and enters the lung through the pulmonary artery. There, the embolus may dissolve, become more fragmented, or grow.

By occluding the pulmonary artery, the embolus prevents alveoli from producing enough surfactant to maintain alveolar integrity. As a result, alveoli collapse and atelectasis develops. If the embolus enlarges, it may clog most or all pulmonary vessels and cause right-sided heart failure and death.

Who’s at risk for pulmonary embolism?

Many disorders and treatments increase the risk of pulmonary embolism. Risk is particularly high for patients who have had recent surgery. The anesthetic used during surgery can injure lung vessels, and surgery or prolonged immobility can promote venous stasis, further compounding the risk.

Predisposing disorders

Lung disorders, especially chronic types

Cardiac disorders

Infection

Cancer

History of thromboembolism, thrombophlebitis, or venous insufficiency

Sickle cell disease

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Polycythemia

Osteomyelitis

Long-bone fracture

Manipulation or disconnection of central lines

Coagulation disorders

Venous stasis

Prolonged immobilization

Obesity

Age older than 40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Asthmatic bronchus

Asthmatic bronchus

Lung changes in emphysema

Lung changes in emphysema

Tumor infiltration in lung cancer

Tumor infiltration in lung cancer

Locations of pneumonia

Locations of pneumonia

How pulmonary edema develops

How pulmonary edema develops