Renal and urologic care

Diseases

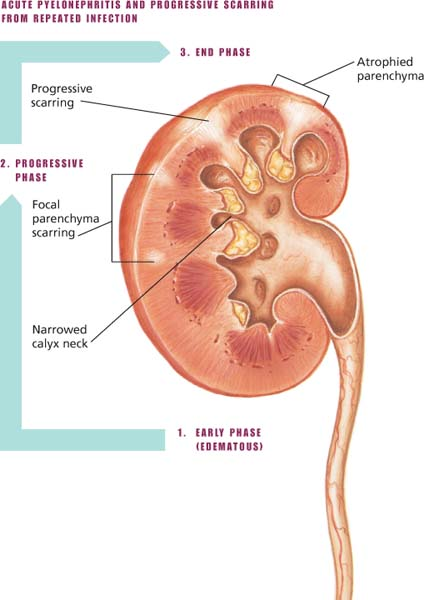

Acute pyelonephritis

Acute pyelonephritis (also called acute interstitial nephritis) is one of the most common renal diseases. With this disorder, sudden inflammation is caused by bacterial infection of the kidneys. It occurs mainly in the interstitial tissue and the renal pelvis, and occasionally in the renal tubules. It may affect one or both kidneys.

Typically, the infection spreads from the bladder to the ureters and then to the kidneys, commonly through vesicoureteral reflux. Vesicoureteral reflux may result from a congenital weakness at the junction of the ureter and the bladder. The infecting bacteria are usually normal intestinal and fecal flora that grow readily in urine. Infection may also result from procedures that involve the use of instruments (such as catheterization, cystoscopy, and urologic surgery) or from a hematogenic infection (such as septicemia and endocarditis).

Pyelonephritis may result from an inability to empty the bladder (for example, in patients with neurogenic bladder), urinary stasis, or urinary obstruction caused by tumors, strictures, or benign prostatic hyperplasia.

With treatment and continued follow-up care, the prognosis is good and extensive permanent damage is rare.

Signs and symptoms

Pain over one or both kidneys

Urinary urgency and frequency

Burning during urination

Dysuria

Nocturia

Hematuria (usually microscopic but possibly gross)

Flank pain upon palpation

Cloudy urine with an ammonia-like or fishy odor

Temperature of 102° F (38.9° C) or higher

Chills

Anorexia

General fatigue

Occasional proteinuria

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy appropriate to the specific infecting organism after identification by urine culture and sensitivity studies, such as:

Enterococcus that requires ampicillin (Principen), penicillin G, or vancomycin

Staphylococcus that requires penicillin G or semisynthetic penicillin such as nafcillin, or cephalosporin for resistant bacterium

Escherichia coli that requires sulfisoxazole (Eryzole), nalidixic acid (NegGram), nitrofurantoin (Macrobid), or ciprofloxacin (Cipro)

Klebsiella that requires cephalosporin, gentamicin, or tobramycin

Proteus that requires ampicillin, sulfisoxazole, nalidixic acid, or cephalosporin

Pseudomonas that requires ciprofloxacin (Cipro), gentamicin, tobramycin, or carbenicillin (Geocillin)

Broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as ampicillin or cephalexin (Keflex) (for non-identifiable infecting organism)

Nursing considerations

Administer antipyretics for fever.

Encourage fluids to achieve a urine output of more than 2,000 ml/24 hours. This helps empty the bladder of contaminated urine and prevents calculus formation. Don’t encourage intake of more than 2 to 3 qt (2 to 3 L) because this can decrease the effectiveness of the antibiotics.

Provide an acid-ash diet to prevent calculus formation.

Observe sterile technique during catheter insertion and care.

Be sure to refrigerate or culture a urine specimen within 30 minutes of collection to prevent overgrowth of bacteria.

Teaching about pyelonephritis

Teaching about pyelonephritis

Encourage the patient to urinate frequently to prevent stasis of urine.

Instruct a female patient to avoid bacterial contamination by always wiping the perineum from front to back.

Teach proper technique for collecting a clean-catch urine specimen.

Stress the need to complete the prescribed antibiotic regimen, even after symptoms subside. Encourage long-term follow-up care for a high-risk patient.

Advise routine checkups for a patient with a history of urinary tract infections. Teach him to recognize signs and symptoms of infection, such as cloudy urine, burning on urination, and urinary urgency and frequency, especially when accompanied by a low-grade fever and back pain.

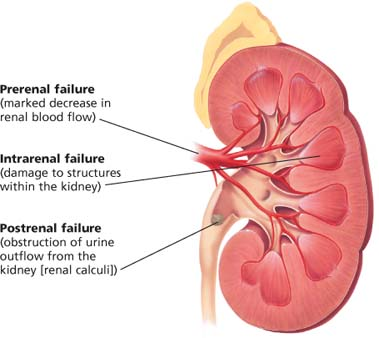

Acute renal failure

About 5% of all hospitalized patients develop acute renal failure, the sudden interruption of renal function resulting from obstruction, reduced circulation, or renal parenchymal disease. This condition is classified as prerenal, intrarenal, or postrenal and normally passes through three distinct phases: oliguric, diuretic, and recovery. It may be reversible with medical treatment. If it progresses to end-stage renal disease and dialysis isn’t initiated, uremia and death are probable.

The three types of acute renal failure each have separate causes. Prerenal failure results from conditions that diminish blood flow to the kidneys. Between 40% and 80% of all cases of acute renal failure are caused by prerenal azotemia. Intrarenal failure (also called intrinsic or parenchymal renal failure) results from damage to the kidneys themselves, usually from acute tubular necrosis. Postrenal failure results from bilateral obstruction of urine outflow.

Causes of acute renal failure

Acute renal failure can be classified as prerenal, intrarenal, or postrenal. All conditions that lead to prerenal failure impair renal perfusion, resulting in decreased glomerular filtration rate and increased proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium and water. Intrarenal failure results from damage to the kidneys themselves; postrenal failure results from obstruction of urine flow. Listed here are the possible causes of each type of acute renal failure.

| Prerenal failure | Intrarenal failure | Postrenal failure |

|---|---|---|

Cardiovascular disorders

| ||

Acute tubular necrosis

| ||

Bladder obstruction

|

Signs and symptoms

Recent history of fever

Chills

Headache

GI problems, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation

Irritability

Drowsiness

Confusion

Seizures and coma (advanced stages)

Oliguria (less than 500 ml/24 hours) or anuria (less than 100 ml/24 hours)

Petechiae and ecchymoses

Hematemesis

Dry, pruritic skin

Uremic frost (rare)

Dry mucous membranes

Uremic breath odor

Muscle weakness (with hyperkalemia)

Tachycardia

Irregular heart rhythm

Bibasilar crackles and peripheral edema (with heart failure)

Abdominal pain (with pancreatitis or peritonitis)

Edema in lower extremities or facial edema

Stages of acute renal failure

Before assessing a patient with renal failure, review the stages of the condition and the characteristics as described here.

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Onset (hours to several days) | Begins with the precipitating event, which is usually recognized in retrospect. Nitrogenous waste products (blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and creatinine) begin to accumulate in serum. |

| Oliguric* (usually 1 to 2 weeks) | Urine output is 100 to 400 ml/24 hours. Serum shows increasing levels of BUN, creatinine, potassium phosphate, and magnesium and decreasing levels of calcium and bicarbonate. Sodium is increased but is diluted by water retention. |

| Diuretic (2 to 6 weeks) | Kidneys lose ability to concentrate urine; urine is diluted with output of 3,000 to 10,000 ml/24 hours. BUN and creatinine levels begin to decrease. A return to normal BUN and creatinine levels signals the end of this stage. Normal renal tubular function is reestablished unless some residual damage remains. |

| Recovery (up to 1 year) | Renal function and electrolyte levels return to normal unless irreversible renal damage has occurred. |

| *Note: Some patients don’t experience the oliguric phase of acute renal failure. |

Treatment

Maintaining fluid balance, blood volume, and blood pressure during and after surgery

Identification and treatment of reversible causes, such as nephrotoxic drug therapy and volume depletion

Diet high in calories and low in protein, sodium, and potassium, with supplemental vitamins and restricted fluids

Meticulous electrolyte monitoring to detect hyperkalemia

Hypertonic glucose-and-insulin infusions and sodium bicarbonate (I.V.) and sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) by mouth or enema to remove potassium from the body (for hyperkalemia)

Hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis

Early initiation of diuretic therapy

Continuous renal replacement therapy (for hemodynamically unstable patients or those refractory to hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis)

Nursing considerations

Measure and record intake and output of all fluids, including wound drainage, nasogastric tube output, and diarrhea.

Be sure to weigh the patient daily especially before and after dialysis.

Evaluate all drugs the patient is taking to identify those that may affect or be affected by renal function.

Assess hematocrit and hemoglobin levels and replace blood components as ordered.

Monitor vital signs. Watch for and report signs of pericarditis (pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, and pericardial friction rub), inadequate renal perfusion (hypotension), and acidosis.

Maintain proper electrolyte balance. Strictly monitor potassium levels. Watch for symptoms of hyperkalemia and report them immediately. Avoid administering medications that contain potassium.

Maintain nutritional status. Provide a diet high in calories and low in protein, sodium, and potassium, with vitamin supplements.

Monitor the patient for signs and symptoms of developing acidosis, such as decreased level of consciousness, development of cardiac arrhythmias, and changes in the rate and depth of respirations.

Prevent complications of immobility by encouraging frequent coughing and deep breathing and by performing passive range-of-motion exercises.

Provide mouth care frequently to lubricate dry mucous membranes.

Monitor GI bleeding by testing all stools for occult blood.

Provide meticulous perineal care to reduce the risk of ascending urinary tract infection (in women) and to protect skin integrity.

If the patient requires hemodialysis, check the vascular access site (arteriovenous fistula or graft, subclavian or femoral catheter) every 2 hours for patency and signs of clotting. Don’t use the arm with the graft or fistula for measuring blood pressure, inserting I.V. lines, or drawing blood.

During hemodialysis, monitor vital signs, clotting times, blood flow, vascular access site function, and arterial and venous pressures.

After hemodialysis, monitor vital signs, check the vascular access site, weigh the patient, and watch for signs of fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Provide emotional support to the patient and his family.

Administer prescribed medications after hemodialysis is completed. Many medications are removed from the blood during treatment.

Teaching about acute renal failure

Teaching about acute renal failure

Reassure the patient and his family by clearly explaining all diagnostic tests, treatments, and procedures.

Tell the patient about his prescribed medications, and stress the importance of complying with the regimen.

Stress the importance of following the prescribed diet and fluid allowance.

Instruct the patient to weigh himself daily and report changes of 3 lb (1.4 kg) or more immediately.

Advise the patient against overexertion. If he becomes dyspneic or short of breath during normal activity, tell him to report this finding to his physician.

Teach the patient how to recognize edema, and tell him to report this finding to the physician.

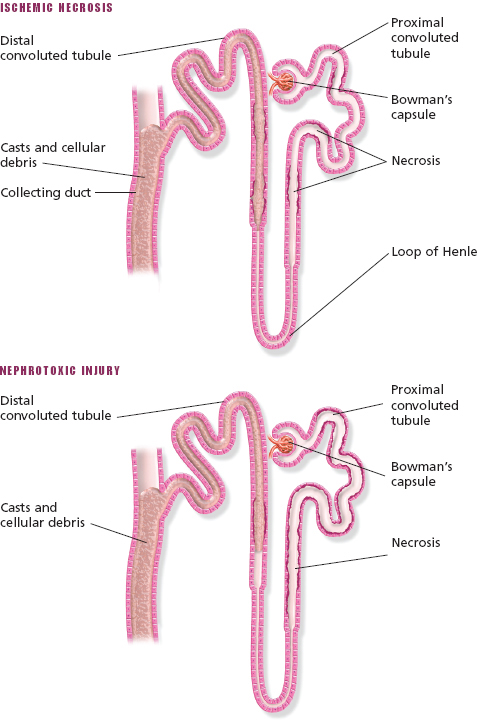

Acute tubular necrosis

Acute tubular necrosis (also called acute tubulointerstitial nephritis) is the most common cause of acute renal failure in critically ill patients or those who have undergone extensive surgery (accounting for about 75% of all cases). This disorder injures the tubular segment of the nephron, causing renal failure and uremic syndrome.

Acute tubular necrosis results from ischemic necrosis or nephrotoxic injury. In ischemic necrosis, disruption of blood flow to the kidneys may result from circulatory collapse, severe hypotension, trauma, hemorrhage, dehydration, cardiogenic or septic shock, surgery, anesthetics, or transfusion reactions. Nephrotoxic injury may follow ingestion or inhalation of certain chemicals, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics, amphotericin B (Abelcet), and radiographic contrast agents, or it may result from prolonged use of aspirin-containing agents or a hypersensitivity reaction of the kidneys.

Signs and symptoms

History of an ischemic or a nephrotoxic injury

Oliguria (less than 500 ml/24 hours)

Petechiae and ecchymoses

Hematemesis

Dry and pruritic skin

Uremic frost (rare)

Dry mucous membranes and uremic breath odor

Muscle weakness (with hyperkalemia)

Lethargy and somnolence

Disorientation

Asterixis

Agitation

Myoclonic muscle twitching

Seizures

Tachycardia

Irregular heart rhythm

Pericardial friction rub indicating pericarditis (rare)

Bibasilar crackles and peripheral edema (with heart failure)

Abdominal pain (with pancreatitis or peritonitis)

Peripheral edema (if heart failure is present)

Fever and chills (with infection)

Treatment

Initially, administration of diuretics and infusion of fluids (large amounts) to flush tubules of cellular casts and debris and to replace fluid loss

Long-term fluid management that requires daily replacement of projected and calculated losses (including insensible loss)

Transfusion of packed red blood cells (RBCs) (for anemia)

Antibiotics (for infection)

Emergency I.V. administration of 50% glucose, regular insulin, and sodium bicarbonate (for hyperkalemia)

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) to reduce extracellular potassium levels (by mouth or enema)

Hemodialysis (for catabolic patient)

Nursing considerations

Maintain fluid balance and watch for fluid overload, a common complication of therapy. Record intake and output, including wound drainage, nasogastric tube output, and hemodialysis balances. Weigh the patient at the same time every day.

Monitor hemoglobin (Hb) level and hematocrit, and administer blood products as needed. Use fresh packed RBCs instead of whole blood, especially in an elderly patient, to prevent fluid overload and heart failure.

Maintain electrolyte balance. Monitor laboratory test results and report imbalances. Restrict foods that contain sodium and potassium, such as bananas, prunes, orange juice, chocolate, tomatoes, and baked potatoes. Check for potassium content in prescribed medications (for example, potassium penicillin).

Provide adequate calories and essential amino acids while restricting protein intake to maintain an anabolic state. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) may be indicated for a severely debilitated or catabolic patient. If the patient is receiving TPN, keep his skin meticulously clean.

Use sterile technique, particularly when handling catheters, because the debilitated patient is vulnerable to infection. Immediately report fever, chills, delayed wound healing, or flank pain if the patient has an indwelling catheter.

If anemia worsens, causing pallor, weakness, or lethargy with decreased Hb level, administer RBCs as ordered.

For acidosis, give sodium bicarbonate or assist with dialysis in severe cases as ordered. Watch for hypotension, which diminishes renal perfusion and decreases urine output.

Perform passive range-of-motion exercises.

Teaching about acute tubular necrosis

Teaching about acute tubular necrosis

Teach the patient the signs of infection, and tell him to report them to the physician immediately. Remind him to stay away from crowds and any infected person.

Review the prescribed diet, including restrictions, and stress the importance of adhering to it.

Teach the patient how to cough and perform deep breathing to prevent pulmonary complications.

Fully explain each procedure to the patient and his family as often as necessary, and help them set goals that are realistic for the patient’s prognosis.

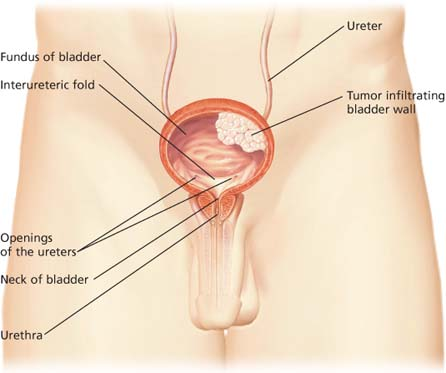

Bladder cancer

Benign or malignant tumors may develop on the bladder wall surface or grow within the wall and quickly invade underlying muscles. About 90% of bladder cancers are transitional cell carcinomas, arising from the transitional epithelium of mucous membranes.

Bladder tumors are most prevalent in people older than age 50, are more common in males than in females, and occur more often in densely populated industrial areas.

Certain environmental carcinogens, such as tobacco, 2-naphthylamine, and nitrates are known to predispose a person to transitional cell tumors. Exposure to these carcinogens places certain industrial workers at higher risk for developing such tumors, including rubber workers, weavers, aniline dye workers, hairdressers, petroleum workers, spray painters, and leather finishers.

Signs and symptoms

Gross, painless, intermittent hematuria (typically with clots)

Suprapubic pain after voiding (suggesting invasive lesions)

Bladder irritability

Urinary frequency

Nocturia

Dribbling

Flank pain (with obstructed ureter)

Treatment

Superficial bladder tumors

Cystoscopic transurethral resection and fulguration

Intravesical chemotherapy to prevent recurrence (for tumors in many sites)

Intravesical administration of live, attenuated bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine (for primary and relapsed carcinoma in situ)

Segmental bladder resection to remove a full-thickness section of the bladder (only for tumors not near bladder neck or ureteral orifices)

Bladder instillations of thiotepa after transurethral resection

Infiltrating bladder tumors

Radical cystectomy and urinary diversion (usually an ileal conduit)

Advanced bladder cancer

Cystectomy

Radiation therapy

Combination systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin (Platinol) (most effective)

Doxorubicin (Doxil), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), and fluorouracil (may arrest the cancer)

Nursing considerations

Listen to the patient’s fears and concerns. Stay with him during periods of severe stress and anxiety, and provide psychological support.

To relieve discomfort, provide ordered pain medications as necessary.

Before surgery, offer information and support when the patient and enterostomal therapist select a stoma site.

After surgery, encourage the patient to look at the stoma.

After ileal conduit surgery, watch for these complications: wound infection, enteric fistulas, urine leaks, ureteral obstruction, bowel obstruction, and pelvic abscesses.

After radical cystectomy and construction of a urine reservoir, watch for these complications: incontinence, difficult catheterization, urine reflux, obstruction, bacteriuria, and electrolyte imbalances.

If the patient is receiving chemotherapy, watch for complications resulting from the particular drug regimen.

If the patient is having radiation therapy, watch for these complications: radiation enteritis, colitis, and skin reactions.

Bladder cancer treatments

Therapies that offer promise for patients with bladder cancer include photodynamic, gene, and immunotoxin therapies.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy requires I.V. injection of a photosensitizing agent called hematoporphyrin derivative (HPD). Malignant tissue appears to have an affinity for HPD, so superficial bladder cancer cells readily absorb the drug. A cystoscope is then used to introduce laser energy into the bladder; exposing the HPD-impregnated tumor cells to laser energy kills them.

However, HPD sensitizes not only tumor tissue but also normal tissue, so the patient who receives this therapy must avoid sunlight for about 30 days. Precautions involve wearing protective clothing (including gloves and a face mask), drawing heavy curtains at home during the day, scheduling outdoor travel for night, and conducting exercises inside or outdoors at night to promote circulation, joint mobility, and muscle activity. After 30 days, the patient can gradually return to normal daylight activities.

Gene therapy

Researchers have determined that mutations in tumor suppressor cells, such as p53, cause abnormal bladder cancer cell growth. Although still in the investigation stages, the researchers are studying methods of infecting bladder cancer cells with viruses that contain a normal p53 gene in the hope that the normal gene, when placed in a bladder cancer cell, will cause normal cell growth.

Immunotoxin therapy

Although still in investigational stages, researchers have hope that immunotoxin therapy will someday effectively treat bladder cancer. Immunotoxins are laboratory-manufactured antibodies with powerful toxins attached to them that can recognize cancer cells. After an antibody recognizes a cancer cell, it releases the toxin, which enters the cancer cell and kills it.

Teaching about bladder cancer

Teaching about bladder cancer

Tell the patient what to expect from diagnostic tests. For example, make sure he understands that he may be anesthetized for cystoscopy. After the test results are known, explain the implications to the patient and his family.

Provide complete preoperative teaching. Discuss equipment and procedures that the patient can expect postoperatively. Demonstrate essential coughing and deep-breathing exercises. Encourage the patient to ask questions.

For the patient with a urinary stoma:

Teach the patient how to care for his urinary stoma. Encourage appropriate caregivers to attend the teaching session. Advise them beforehand that a negative reaction to the stoma can impede the patient’s adjustment.

If the patient is to wear a urine collection pouch, teach him how to prepare and apply it. First, find out whether he will wear a reusable pouch or a disposable pouch. If he chooses a reusable pouch, he needs at least two to wear alternately.

Instruct the patient to remeasure the stoma after he goes home in case the size changes.

Advise him to make sure the pouch has a push-button or twist-type valve at the bottom to allow for drainage.

Tell him to empty the pouch when it’s one-third full, or every 2 to 3 hours.

Offer the patient tips on effective skin seal. Explain that urine tends to destroy skin barriers that contain mostly karaya (a natural skin barrier). Suggest that he select a barrier made of urine-resistant synthetics with little or no karaya. Advise him to check the pouch frequently to ensure that the skin seal remains intact. Tell the patient that the ileal conduit stoma should reach its permanent size about 2 to 4 months after surgery.

Explain that the surgeon constructs the ileal conduit from the intestine, which normally produces mucus. For this reason, the patient will see mucus in the drained urine. Assure him that this finding is normal.

Teach the patient how to keep the skin around the stoma clean and free from irritation. Instruct him to remove the pouch, wash the skin with water and mild soap, and rinse well with clear water to remove soapy residue. Tell him to gently pat the skin dry. Never rub.

Demonstrate how to place a gauze sponge soaked in vinegar water (1 part vinegar to 3 parts water) over the stoma for a few minutes to prevent a buildup of uric acid crystals. When he cares for his skin, suggest that he place a rolled-up dry sponge over the stoma to collect (or wick) draining urine.

Next, instruct him to coat his skin with a silicone skin protectant and then cover with the collection pouch. Advise him to apply hydrocolloid powder to irritated or eroded skin.

Postoperatively, tell the patient with a urinary stoma to avoid heavy lifting and contact sports. Encourage him to participate in his usual athletic and physical activities.

Before discharge, arrange for follow-up home nursing care. Also refer the patient for services provided by the enterostomal therapist.

Provide contact information for the United Ostomy Association or American Cancer Society for additional education and support.

Chronic glomerulonephritis

Chronic glomerulonephritis is a slowly progressive disease characterized by inflammation of the glomeruli, which results in sclerosis, scarring and, eventually, renal failure. This condition normally remains subclinical until the progressive phase begins. By the time it produces symptoms, chronic glomerulonephritis is usually irreversible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Phases of pyelonephritis

Phases of pyelonephritis

Mechanisms of acute renal failure

Mechanisms of acute renal failure

Ischemic necrosis and nephrotoxic injury

Ischemic necrosis and nephrotoxic injury

Looking at a bladder tumor

Looking at a bladder tumor