R

RAPE-TRAUMA SYNDROME

The term “rape” refers to nonconsensual sexual intercourse. Rape inflicts varying degrees of physical and psychological trauma. Rape-trauma syndrome typically occurs during the period following the rape or attempted rape. It refers to the victim’s short- and long-term reactions and to the methods she uses to cope with the trauma. In most cases, the rapist is a man and the victim is a woman. However, rape does occur between persons of the same sex, especially in prisons. Children are often victims of rape; most of the time these cases involve manual, oral, or genital contact with the child’s genitalia. Usually, the rapist is a member of the child’s family. In some instances, a man or child is sexually abused by a woman.

The prognosis is promising if the rape victim receives physical and emotional support and counseling to help her deal with her feelings. The patient who articulates her feelings can cope with fears, interact with others, and return to normal routines faster than the patient who doesn’t.

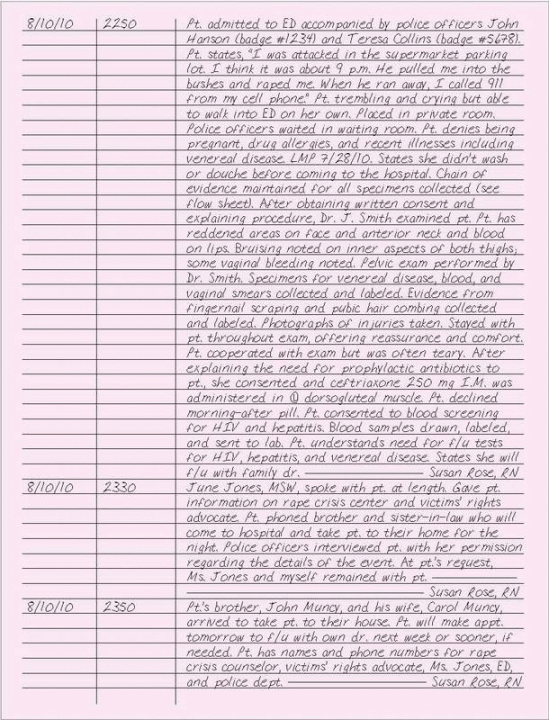

Be objective and precise when documenting care for a patient who was raped. Your notes may be used as evidence if the rapist is tried.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of each entry. Record the patient’s statements, using her own words, in quotes. Also, document objective information provided by others. Include the time that the patient arrived at the facility, date and time of the alleged rape, and time that she was examined. Ask the patient about allergies to penicillin and other drugs, recent illnesses

(especially venereal disease), the possibility of pregnancy before the attack, the date of her last menstrual period, and details of her obstetric and gynecologic history. Describe the patient’s emotional state and behaviors.

(especially venereal disease), the possibility of pregnancy before the attack, the date of her last menstrual period, and details of her obstetric and gynecologic history. Describe the patient’s emotional state and behaviors.

Make sure the doctor has obtained the patient’s informed consent for treatment. Note whether she douched, bathed, or washed before coming to the facility. If the case comes to trial, specimens will be used for evidence, so accuracy is essential. Most emergency departments have special kits for rape victims, with containers for specimens. During the examination, make sure all specimens collected (including fingernail scrapings, pubic hair combings, semen, and gonorrhea culture) are labeled carefully with the patient’s name, doctor’s name, and location from which the specimen was obtained. Place all the patient’s clothing in paper, not plastic, bags. If clothing is placed in plastic bags, secretions and seminal stains will become moldy, destroying valuable evidence. Label each bag and its contents. List all specimens in your note, and record to whom these specimens were given. Document whether photographs were taken and by whom.

This examination is typically very distressing for the rape victim. Reassure her and allow her as much control as possible. If the patient wishes, ask a counselor to stay with her throughout the examination, and remember to document the name of the individual. Counseling helps the patient identify coping mechanisms. She may relate more easily to a counselor of the same sex. Before the patient’s pelvic area is examined, take her vital signs and document them. If the patient is wearing a tampon, remove it, wrap it, and label it as evidence.

On the medication administration record, list all medications administered, such as antibiotics and birth control prophylaxis (for example, morning-after pills). Explain possible adverse effects, what to expect of the medication, and signs and symptoms to report. Document all teaching administered, and provide the patient with written instructions before discharge. Record care given to such injuries as lacerations, cuts, or areas of swelling. Document whether the patient was offered and received testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B and C. Include whether prophylaxis for hepatitis was given. Chart that you told the patient the importance of follow-up testing in 5 to 6 days for gonorrhea and syphilis. Record the names and telephone numbers of contact persons for local resources, including rape crisis centers, victims’ rights advocates, and local law enforcement. Chart any other education and support that you give to the patient.

|

REFUSAL OF TREATMENT

Any mentally competent adult can refuse treatment. In most cases, the health care personnel responsible for the patient’s care can remain free from legal jeopardy as long as they fully inform the patient about his medical condition, the proposed testing or treatment, and the likely consequences of refusing treatment. The courts recognize a competent adult’s right to refuse medical treatment, even when that refusal will clearly lead to his death. (See Respecting a patient’s right to refuse care, page 350.)

RESPECTING A PATIENT’S RIGHT TO REFUSE CARE

RESPECTING A PATIENT’S RIGHT TO REFUSE CARENrespectinga patientient’s request to refuse treatment.A patient can sue you for battery — intentionally touching another person without authorization—for simply following a doctor’s orders.

To overrule the patient’s decision, the doctor or your facility must obtain a court order. Only then are you legally authorized to administer the treatment.

When your patient refuses treatment, inform him of the risks involved in making such a decision. If possible, inform him in writing. If he continues to refuse treatment, notify the doctor, who will choose the most appropriate plan of action. Be sure to provide a translator if the patient has a language barrier, per facility policy.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

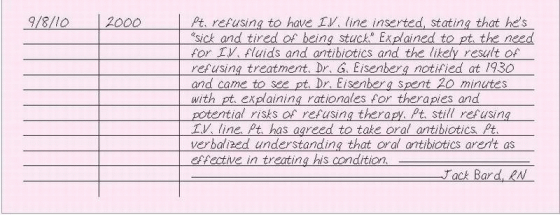

Record the date and time of the patient’s refusal of treatment. Be sure to document the patient’s exact words in the chart as well as a neurologic assessment that describes the patient’s mental status. To protect yourself legally, document that you didn’t provide the prescribed treatment because the patient refused it. Then ask the patient to sign a refusal-of-treatment release form.

If the patient refuses to sign the release form, document this refusal in your progress note along with the reason for refusal of treatment, if known. For additional protection, your facility’s policy may require you to ask the patient’s spouse or closest relative to sign another refusal-of-treatment release form. Document which relative signs the form. If an interpreter is used, document the name of the translator, such as AT&T phone services.

|

REFUSAL TO LEAVE, VISITOR’S

Visitors can be an important source of support for patients and may help the patient with his needs. On occasion, visitors may be unable to give support and may, in fact, be detrimental to the patient. This may be seen through objective measurement, or may even be verbalized by the patient to you privately, when the visitor isn’t present. At times, visitors may interfere with patient care. At the time of admission, explain the visiting policy to the family and ensure that they understand why it’s necessary, referring to the needs of the patient (to conserve energy, to rest, or to reduce pain). Provide a telephone number for the family spokesperson to call at predetermined times to get updates and ask questions, within the limits of patient confidentiality.

There may be situations in which visitors may refuse to leave. This is commonly related to anxiety and concern about the patient. Remember that family members react differently to stress and need to be encouraged to take care of themselves as well. Educate them about nursing routines and visiting policies, reiterating, as necessary, the reasons for limiting visitation.

In special circumstances, such as when a patient is critically ill, visitors may be permitted to stay or visit at times other than the scheduled visiting hours if the nurse caring for the patient or the nursing supervisor feels it’s in the patient’s or family’s best interest.

If family members continue to refuse to leave despite all interventions, call the nursing supervisor and security. By all means, don’t place yourself in a dangerous situation, such as arguing with the visitor or making physical contact.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

On admission, document that visiting policies were explained to the patient and his family. Note whether written visiting policies were given to them.

When visitors refuse to leave, document what they tell you, using their own words. Note which visitors are present. Also, record what you tell the visitors and their responses, objectively describing their behaviors. Chart the names of the nursing supervisor and security personnel notified, the time of notification, and any instructions given. If a supervisor or security comes to see the visitor, describe what was said and their responses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree