Prenatal Care

In this chapter, you’ll learn:

components of a prenatal patient history and physical assessment

different types of prenatal testing

nutritional needs of the pregnant patient

common discomforts of pregnancy and ways to minimize them.

A look at prenatal care

Prenatal care is essential to the overall health of the neonate and the mother. Traditional elements of prenatal care include assessing the patient, performing prenatal testing, providing nutritional care, and minimizing the discomforts of pregnancy. However, that isn’t where prenatal care ends—or, should we say, where it begins.

|

Prepregnancy prenatal

Believe it or not, prenatal care begins long before pregnancy, when the expectant mother herself is still a child! Ideally, to reduce the risk of complications during pregnancy, a woman needs to maintain good health and nutrition throughout her life. For example, adequate calcium and vitamin D intake during the woman’s infancy and childhood helps to prevent rickets, which can distort pelvic size, resulting in difficulties during birth. Maintaining immunizations protects her from viral diseases such as rubella. In addition, such healthy lifestyle practices as eating a nutritious diet, having positive attitudes about sexuality, practicing safer sex, having regular pelvic examinations, and receiving prompt treatment for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) also contribute to the patient’s health status throughout pregnancy.

After the fact

Prenatal care after the patient has conceived consists of a thorough assessment, including a health history and physical examination, prenatal testing, nutritional care, and reduction of discomfort. Each of these factors should be addressed at the first prenatal visit.

|

Occasion for education

The first prenatal visit is also the time when the pregnant woman and her family can receive information on and counseling about what to expect during pregnancy, including necessary care. This promotes the development of healthy behaviors and helps to prevent complications. Keep in mind that the patient education you provide during pregnancy should vary depending on the age and parity of the woman as well as her cultural background. Warn the patient ahead of time that her first visit may be a long one.

Assessment

The first prenatal visit is the best time to establish baseline data for the pregnant patient. A thorough assessment of the reproductive system should be included. As with other body systems, this assessment depends on an accurate history (see Tips for a successful interview, page 152) and a thorough physical examination.

Share and share alike

Remember to keep the patient informed about assessment findings. Sharing this information with her may help her to comply with health care recommendations and encourage her to seek additional information about any problems or questions that she has later in the pregnancy.

Health history

Information obtained from the patient’s health history helps establish baseline data, which can be used to plan health-promotion strategies for every subsequent visit and identify potential complications. (See Formidable findings, page 153.)

The health history you conduct should be extensive. Be sure to include biographic data, information on the patient’s nutritional status, a medical history, a family history, a gynecologic history, and an obstetric history.

Advice from the experts

Advice from the expertsTips for a successful interview

Here are some tips that can help you obtain an accurate and thorough patient history.

Location

Pregnancy is too private to be discussed in public areas. Make every effort to interview your patient in a private, quiet setting. Trying to talk to a pregnant woman in a crowded area, such as a busy waiting room in a clinic, is rarely effective. Remember patient confidentiality and respect the patient’s privacy, especially when discussing intimate topics.

Checklist

To ensure that your history is complete, be sure to ask about:

the patient’s overall patterns of health and illness

the patient’s medical and surgical history

the patient’s history of pregnancy or abortion

the date of the patient’s last menses and whether her menses are regular or irregular

the patient’s sexual history, including number of partners, frequency, current method of birth control, and satisfaction with chosen method of birth control

the patient’s family history

any allergies the patient has

health-related habits, such as smoking and alcohol use.

Biographic data

When obtaining biographic data, assure the patient that the information will remain confidential. Topics to discuss include age; cultural considerations, such as race and religion; marital status; occupation; and education.

Age

The patient’s age is an important factor because reproductive risks increase among adolescents younger than age 15 and women older than age 35. For example, pregnant adolescents are more likely to have preeclampsia, also known as gestational hypertension. Expectant mothers older than age 35 are at risk for other problematic conditions, including placenta previa; hydatidiform mole; and vascular, neoplastic, and degenerative diseases. (See chapter 6, High-risk pregnancy.)

Formidable findings

When performing your health history and assessment, look for the following findings to determine if a pregnant patient is at risk for complications.

Obstetric history

History of infertility

Grand multiparity

Incompetent cervix

Uterine or cervical anomaly

Previous preterm labor or preterm birth

Previous cesarean birth

Previous infant with macrosomia

Two or more spontaneous or elective abortions

Previous hydatidiform mole or choriocarcinoma

Previous ectopic pregnancy

Previous stillborn neonate or neonatal death

Previous multiple gestation

Previous prolonged labor

Previous low-birth-weight infant

Previous midforceps delivery

Diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero

Previous infant with neurologic deficit, birth injury, or congenital anomaly

Less than 1 year since last pregnancy

Medical history

Cardiac disease

Metabolic disease

Renal disease

Recent urinary tract infection or bacteriuria

GI disorders

Seizure disorders

Family history of severe inherited disorders

Surgery during current pregnancy

Emotional disorders or mental retardation

Previous surgeries, particularly those involving the reproductive organs

Pulmonary disease

Endocrine disorders

Hemoglobinopathies

Sexually transmitted disease (STD)

Chronic hypertension

History of abnormal Papanicolaou smear

Malignancy

Reproductive tract anomalies

Current obstetric status

Inadequate prenatal care

Intrauterine growth-restricted fetus

Large-for-gestational age fetus

Gestational hypertension (preeclampsia)

Abnormal fetal surveillance tests

Hydramnios

Placenta previa

Abnormal presentation

Maternal anemia

Weight gain of less than 10 lb (4.5 kg)

Weight loss of more than 5 lb (2.3 kg)

Overweight or underweight status

Fetal or placenta malformation

Rh sensitization

Preterm labor

Multiple gestation

Premature rupture of membranes

Abruptio placentae

Postdate pregnancy

Fibroid tumors

Fetal manipulation

Cervical cerclage (purse-string suture placed around incompetent cervix to prevent premature opening and subsequent spontaneous abortion)

STD

Maternal infection

Poor immunization status

Psychosocial factors

Inadequate finances

Social problems

Adolescent

Poor nutrition

More than two children at home with no additional support

Lack of acceptance of pregnancy

Attempt at or ideation of suicide

Poor housing

Lack of involvement of father of baby

Minority status

Parental occupation

Inadequate support systems

Dysfunctional grieving

Psychiatric history

Demographic factors

Maternal age younger than 16 or older than 35

Fewer than 11 years of education

Lifestyle

Smoking (more than ten cigarettes per day)

Substance abuse

Long commute to work

Refusal to use seatbelts

Alcohol consumption

Heavy lifting or long periods of standing

Unusual stress

Lack of smoke detectors in the home

Race and religion

The patient’s race and religion, as well as other cultural considerations, may also impact a pregnancy. Obtaining information from your patient about these topics can help you plan patient care. (See Cultural considerations for assessment.) It also gives you greater insight into the patient’s behavior, potential problems in health promotion and maintenance, and ways of coping with illness.

It’s important to learn about the cultural communities in which you work, and become familiar with the cultural practices of those communities. (See Southeast Asian views of pregnancy.)

Bridging the gap

Bridging the gapCultural considerations for assessment

Encourage the patient to discuss her cultural beliefs regarding health, illness, and health care. Be considerate of the patient’s cultural background. Also, be aware that members of many cultures are reluctant to talk about sexual matters and, in some cultures, sexual matters aren’t discussed freely with members of the opposite sex.

A race to detect disease

Because some diseases are more common among certain cultural groups, asking the patient about her race can be an important part of your assessment. It may help guide your prenatal testing. For example, a pregnant black woman should be screened for sickle cell trait because this trait primarily occurs in people of African or Mediterranean descent. A Jewish woman of Eastern European ancestry should be screened for Tay-Sachs disease.

Believe it or not

Religious beliefs and practices can also affect the patient’s health during pregnancy and can predispose her to complications. For example, Amish women may not be immunized against rubella, putting them at risk. In addition, Seventh-Day Adventists traditionally exclude dairy products from their diets, and Jehovah’s Witnesses refuse blood transfusions. Because these practices

could impact prenatal care and the patient’s risk of complications and, thus, you should ask about them when you take the patient’s health history.

could impact prenatal care and the patient’s risk of complications and, thus, you should ask about them when you take the patient’s health history.

Bridging the gap

Bridging the gapSoutheast Asian views of pregnancy

Many women from Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam) don’t seek care during pregnancy because they don’t see it as a time when medical intervention is necessary. In many cases, they’re extremely modest and may find pelvic examinations embarrassing. They may rely on herbs and folk remedies to manage common discomforts of pregnancy. In addition, they may hold the belief that blood isn’t replaceable, which may prevent them from agreeing to laboratory blood studies. Planning care for these patients may require interpreters, classes in prenatal health, and explanations of how health promotion regimens can fit within their cultural belief systems.

Marital status

Knowing the patient’s marital status may help you determine whether family support systems are available. Marital status can also provide information on the size of the patient’s home, her sexual practices, and possible stress factors.

|

Occupation

Ask about the patient’s occupation and work environment to assess possible risk factors. If the patient works in a high-risk environment that exposes her to such hazards as chemicals, inhalants, or radiation, inform her of the dangers of these substances as well as the possible effects on her pregnancy. Knowing the patient’s occupation can also help you to identify such risks as working long hours, lifting heavy objects, and standing for prolonged periods.

Education

The patient’s formal education and her life experiences may influence several aspects of the pregnancy, including:

her attitude toward the pregnancy

her willingness to seek prenatal care

the adequacy of her at-home prenatal care and nutritional status

her knowledge of infant care

her emotional response to childbirth and the responsibilities of parenting.

Obtaining information about the patient’s education can help you to plan appropriate patient teaching.

Nutritional status

Adequate nutrition is especially vital during pregnancy. During the prenatal assessment, take a 24-hour diet history (recall). For more information, see the section on nutritional care later in this chapter.

Medical history

When taking a medical history, find out whether the patient is taking any prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, including vitamins and herbal remedies. Also ask about her smoking practices, alcohol use, and use of illegal drugs. Many drugs—except those with very large molecules, such as insulin and heparin—are able to cross the placenta and affect the fetus. All of the medications the patient is currently taking (including vitamins and herbal

remedies) should be carefully evaluated, and the benefits of each medication should be weighed against the risk to the fetus.

remedies) should be carefully evaluated, and the benefits of each medication should be weighed against the risk to the fetus.

Brushing up on current events

Ask the patient about previous and current medical problems that may jeopardize the pregnancy. For example:

Diabetes can worsen during pregnancy and harm the mother and fetus. Even a woman who has been successfully managing her diabetes may find it challenging during pregnancy because the glucose-insulin regulatory system changes during pregnancy. Every woman appears to develop insulin resistance during pregnancy. In addition, the fetus uses maternal glucose, which may lead to hypoglycemia in the mother. When glucose regulation is poor, the mother is at risk for gestational hypertension and infection, especially monilial infection. The fetus is at risk for asphyxia and stillbirth. Macrosomia (an abnormally large body) may also occur, resulting in an increased risk of birth complications.

Maternal hypertension, which is more common in women with essential hypertension, renal disease, or diabetes, increases the risk of abruptio placentae.

Rubella infection during the first trimester can cause malformation in the developing fetus.

Genital herpes can be transmitted to the neonate during birth. A woman with a history of this disease should have cultures done throughout her pregnancy and may need to deliver by cesarean birth to reduce the risk of transmission.

Obstacle course

Specific problems that you should ask the pregnant patient about include cardiac disorders, respiratory disorders such as tuberculosis; reproductive disorders, such as STDs and endometriosis; phlebitis; epilepsy; and gallbladder disorders. Also, ask the patient if she has a history of urinary tract infections (UTIs), cancer, alcoholism, smoking, drug addiction, or psychiatric problems.

Consider the patient’s education level when using medicinal or scientific terms. For example, she may answer “No” when asked if she has hypertension, but “Yes” when asked if she has high blood pressure.

Family history

Knowing the medical histories of the patient’s family members can help you plan care and guide your assessment by identifying complications for which the patient may be at greater risk. For example, if the patient has a family history of varicose veins, she may inherit a weakness in blood vessel walls that becomes evident when she develops varicosities during pregnancy. Gestational hypertension has also been shown to have a familial tendency, so a family history of gestational hypertension means that the patient

is at greater risk for this complication. Be sure to ask whether there’s a family history of multiple births, congenital diseases or deformities, or mental disability.

is at greater risk for this complication. Be sure to ask whether there’s a family history of multiple births, congenital diseases or deformities, or mental disability.

Don’t dis Dad!

When possible, obtain a medical history from the child’s father as well. Note that some fetal congenital anomalies may be traced to the father’s exposure to environmental hazards.

Gynecologic history

The gynecologic portion of your assessment should include a menstrual history and contraceptive history.

Menstrual history

When obtaining a menstrual history, be sure to ask the patient:

When did your last menstrual period begin?

How many days are there between the start of one of your periods and the start of the next?

Was your last period normal? Was the one before that normal?

How many days does your flow usually last, and is it light, moderate, or heavy?

Have you had bleeding or spotting since your last normal menstrual period?

|

Menarche plays a part

Age at menarche is important when determining pregnancy risks in adolescents. When pregnancy occurs within 3 years of menarche, there’s an increased risk of maternal and fetal mortality. Such a pregnancy also increases the risk of delivering a neonate who’s small for gestational age. Keep in mind that pregnancy can also occur before regular menses are established.

Cramping her style

Ask the patient to describe the intensity of her menstrual cramps. If she indicates that her cramps are very painful, anticipate the need for counseling to help her prepare for labor.

Contraceptive history

To obtain a contraceptive history, ask the patient:

What form of contraception did you use before your pregnancy?

How long did you use it?

Were you satisfied with the method?

Did you experience any complications while on this type of birth control?

Patients who took hormonal contraceptives before becoming pregnant should be asked how long it took to become pregnant once the contraceptives were stopped.

Contraceptive catastrophes

A woman whose pregnancy results from contraceptive failure needs special attention to ensure her medical and emotional well-being. Because the pregnancy wasn’t planned, the woman may have emotional and financial issues. Offering support and referring her to counselors may help her work through these issues and resolve any ambivalence.

If the patient has an intrauterine device (IUD) in place when she becomes pregnant, it will need to be removed immediately because of the risk of spontaneous abortion or preterm labor and delivery.

|

Calculating estimated date of delivery

Based on information obtained in the patient’s menstrual history, you can calculate the patient’s estimated date of delivery (EDD) using Nägele rule: first day of last normal menses, minus 3 months, plus 7 days. Because Nägele rule is based on a 28-day cycle, you may need to vary the calculation for a woman whose menstrual cycle is irregular, prolonged, or shortened.

Obstetric history

Obtaining an obstetric history is another important part of your assessment. The obstetric history provides important information about the patient’s past pregnancies. No matter what age the patient is, don’t assume that this is her first pregnancy. (See Pregnancy classification system.)

Getting the details

The obstetric history should include specific details about past pregnancies, including whether the patient had difficult or long labors and whether she experienced complications. Be sure to document each child’s sex and the location and date of birth.

Do it in order

Always record the patient’s obstetric history chronologically. For a list of the types of information you should include in a complete obstetric history, see Taking an obstetric history, page 160.

What’s your type?

In addition to asking about pregnancy history, ask the woman if she knows her blood type. If the woman’s blood type is Rh-negative,

ask if she received Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) after miscarriages, abortions, or previous births so that you’ll know whether Rh sensitization occurred. If she didn’t receive RhoGAM after any of these situations, her present pregnancy may be at risk for Rh sensitization. Also ask if she’s ever had a blood transfusion to establish possible risk of hepatitis B and HIV exposure.

ask if she received Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM) after miscarriages, abortions, or previous births so that you’ll know whether Rh sensitization occurred. If she didn’t receive RhoGAM after any of these situations, her present pregnancy may be at risk for Rh sensitization. Also ask if she’s ever had a blood transfusion to establish possible risk of hepatitis B and HIV exposure.

Pregnancy classification system

When referring to the obstetric and pregnancy history of a patient, keep these terms in mind:

A primigravida is a woman who’s pregnant for the first time.

A primipara is a woman who has delivered one child past the age of viability.

A multigravida is a woman who has been pregnant before but may not necessarily have carried to term.

A multipara is a woman who has carried two or more pregnancies to viability.

A nulligravida is a woman who has never been and isn’t currently pregnant.

Gravida and para

Two important components of a patient’s obstetric history are her gravida and para status. Gravida represents the number of times the patient has been pregnant. Para refers to the number of children above the age of 20 weeks’ gestation the patient has delivered. The age of viability is the earliest time at which a fetus can survive outside the womb, generally at age 24 weeks or at a weight of more than 400 g (14.1 oz). These two pieces of information are important but provide only the most rudimentary information about the patient’s obstetric history.

The gravida-para code

A slightly more informative system reflects the gravida and para numbers and includes the number of abortions in the patient’s history. For example, G-3, P-2, Ab-1 describes a patient who has been pregnant three times, has had two deliveries after 20 weeks’ gestation, and has had one abortion.

TPAL, GTPAL, and GTPALM

In an attempt to provide more detailed information about the patient’s obstetric history, many facilities now use one of the following classification systems: TPAL, GTPAL, or GTPALM. These systems involve the assignment of numbers to various aspects of a patient’s obstetric past. They offer health care practitioners a way to quickly obtain fairly comprehensive information about a patient’s obstetric history. In particular, these systems offer more detailed information about the patient’s para history.

How often, how many, how viable

In TPAL, the most basic of the three systems, the patient is assigned a four-digit number as follows:

T is the number of pregnancies that ended at term (38 weeks’ gestation or later).

P is the number of pregnancies that ended after 20 weeks’ gestation and before the end of 37 weeks’ gestation.

A is the number of pregnancies that ended in spontaneous or induced abortions.

L is the number of children who are alive at the time the history is obtained.

Taking an obstetric history

When taking the pregnant patient’s obstetric history, be sure to ask her about:

genital tract anomalies

medications used during this pregnancy

history of hepatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, AIDS, blood transfusions, and herpes or other STDs

partner’s history of STDs

previous abortions

history of infertility.

Pregnancy particulars

Also ask the patient about past pregnancies. Be sure to note the number of past full-term and preterm pregnancies and obtain the following information about each of the patient’s past pregnancies, if applicable:

Was the pregnancy planned?

Did any complications—such as spotting, swelling of the hands and feet, surgery, or falls—occur?

Did the patient receive prenatal care? If so, when did she start?

Did she take any medications? If so, what were they? How long did she take them? Why?

What was the duration of the pregnancy?

How was the pregnancy overall for the patient?

Birth and baby specifics

Also, obtain the following information about the birth and postpartum condition of all previous pregnancies:

What was the duration of labor?

What type of birth was it?

What type of anesthesia, if any, did the patient have?

Did the patient experience any complications during pregnancy or labor?

What were the birthplace, condition, sex, weight, and Rh factor of the neonate?

Was the labor as she had expected it? Better? Worse?

Did she have stitches after birth?

What was the condition of the infant after birth?

What was the infant’s Apgar score?

Was special care needed for the infant? If so, what?

Did the neonate experience any problems during the first several days after birth?

What’s the child’s present state of health?

Was the infant discharged from the heath care facility with the mother?

Did the patient experience any postpartum problems?

Note that the patient’s gravida number remains the same, but the TPAL systems allow subclassification of her para status. In most cases, a practitioner includes the patient’s gravida status in addition to her TPAL number. Here are some examples:

A woman who has had two previous pregnancies, has delivered two term children, and is pregnant again is a gravida 3 and is assigned a TPAL of 2-0-0-2.

A woman who has had two abortions at 12 weeks (under the age of viability) and is pregnant again is a gravida 3 and is assigned a TPAL of 0-0-2-0.

A woman who is pregnant for the sixth time, has delivered four term children and one preterm child, and has had one spontaneous abortion and one elective abortion is a gravida 6 and is assigned a TPAL of 4-1-2-5.

|

Details, details

More comprehensive systems for classifying pregnancy status include the GTPAL and GTPALM systems. These classification tools provide greater detail about the patient’s pregnancy history. In the GTPAL system, the patient’s gravida status is incorporated into her TPAL number. In GTPALM, a number is added to the GTPAL to represent the number of multiple pregnancies the patient has experienced (M). Note that a patient who hasn’t given birth to multiple pregnancies doesn’t receive a number to represent M.

Here are some examples:

If a woman has had two previous pregnancies, has delivered two term children, and is currently pregnant, she’s assigned a GTPAL of 3-2-0-0-2.

If a woman who’s pregnant with twins delivers at 35 weeks’ gestation and the neonates survive, she’s classified as a gravida 1, para 2 and is assigned a GTPAL of 1-0-2-0-2. Using the GTPALM system, the same woman would be identified as 1-0-2-0-2-1.

|

Preventing history from repeating itself

If the patient is a multigravida, you’ll want to know about any complications that affected her previous pregnancies. A woman who has delivered one or more large neonates (more than 4.1 kg [9 lb]) or who has a history of recurrent Candida infections or unexplained unsuccessful pregnancies should be screened for obesity and a family history of diabetes. A history of recurrent second-trimester abortions may indicate an incompetent cervix.

Physical assessment

Physical assessment should occur throughout pregnancy, starting with the mother’s first prenatal visit and continuing throughout labor, delivery, and the postpartum period. Physical assessment includes evaluation of maternal and fetal well-being. At each assessment stage, keep in mind the interdependence of the mother and fetus. Changes in the mother’s health may affect fetal health, and changes in fetal health may affect the mother’s physical and emotional health.

|

Rounding the baselines

At the first prenatal visit, measurements of height and weight establish baselines for the patient and allow comparison with expected values throughout the pregnancy. Vital signs, including blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse rate, are also measured for baseline assessment. (See Monitoring vital signs, page 162.)

Scheduled surveillance

Prenatal care visits are usually scheduled every 4 weeks for the first 28 weeks of pregnancy, every 2 weeks until the 36th week, and then weekly until delivery, which usually occurs between weeks 38 and 42. Women who have known risk factors for complications and those who develop complications during the pregnancy require more frequent visits.

Advice from the experts

Advice from the expertsMonitoring vital signs

Monitoring the patient’s vital signs, especially blood pressure, during each prenatal visit is an important part of ongoing assessment. A sudden increase in blood pressure is a danger sign of gestational hypertension. Likewise, a sudden increase in pulse or respiratory rate may suggest bleeding, such as in an early placenta previa or an abruption.

Be sure to report any of these signs or alterations in the patient’s vital signs to the health care practitioner for further assessment and evaluation.

And now back to our regularly scheduled visit

Regular prenatal visits usually consist of weight measurements, vital sign checks, palpation of the abdomen, and fundal height checks. You should also assess the patient for preterm labor symptoms, fetal heart tones, and edema. Also, be sure to ask her if she has felt her baby move. (See Assessing pregnancy by weeks.)

Getting started

At the start of the first prenatal visit, the woman should undress, put on a gown, and empty her bladder. Emptying the bladder makes the pelvic examination more comfortable for her, allows for easier identification of pelvic organs, and provides a urine specimen for laboratory testing.

Head-to-toe assessment

A thorough physical assessment should include inspection of the patient’s general appearance, head and scalp, eyes, nose, ears, mouth, neck, breasts, heart, lungs, back, rectum, extremities, and skin.

|

General appearance

Inspect the patient’s general appearance. This helps form an impression of the woman’s overall health and well-being. The manner in which a patient dresses and speaks, in addition to her body posture, can reveal how she feels about herself. Also inspect for signs of intimate partner violence. Be sure to document your findings.

Head and scalp

Examine the head and scalp for symmetry, normal contour, and tenderness. Check the hair for distribution, thickness, dryness or oiliness, and use of hair dye. Look for chloasma, an extra pigment on the face that may accompany pregnancy. Dryness or sparseness of hair suggests poor nutrition. Lack of cleanliness may suggest fatigue.

Assessing pregnancy by weeks

Here are some assessment findings you can expect as pregnancy progresses.

Weeks 1 to 4

Amenorrhea occurs.

Breasts begin to change.

Immunologic pregnancy tests become positive: Radioimmunoassay test results are positive a few days after implantation; urine human chorionic gonadotropin test results are positive 10 to 14 days after amenorrhea occurs.

Nausea and vomiting may begin between the 4th and 6th weeks.

Weeks 5 to 8

Goodell sign occurs (softening of cervix and vagina).

Ladin sign occurs (softening of uterine isthmus).

Hegar sign occurs (softening of lower uterine segment).

Chadwick sign appears (purple-blue coloration of the vagina, cervix, and vulva).

McDonald sign appears (easy flexion of the fundus toward the cervix).

Braun von Fernwald sign occurs (irregular softening and enlargement of the uterine fundus at the site of implantation).

Piskacek sign may occur (asymmetrical softening and enlargement of the uterus).

The cervical mucus plug forms.

Uterus changes from pear shape to globular.

Urinary frequency and urgency occur.

Weeks 9 to 12

Fetal heartbeat is detected using an ultrasonic stethoscope.

Nausea, vomiting, and urinary frequency and urgency lessen.

By the 12th week, the uterus is palpable just above the symphysis pubis.

Weeks 13 to 17

Mother gains 10 to 12 lb (4.5 to 5.5 kg) during the second trimester.

Uterine soufflé (sound made by the blood within the arteries of a gravid uterus) is heard on auscultation.

Mother’s heartbeat increases by about 10 beats/minute between 14 and 30 weeks’ gestation. The rate is maintained until 40 weeks’ gestation.

By the 16th week, the mother’s thyroid gland enlarges by about 25%, and the uterine fundus is palpable halfway between the symphysis pubis and the umbilicus.

Maternal recognition of fetal movements, or quickening, occurs between 16 and 20 weeks’ gestation.

Weeks 18 to 22

The uterine fundus is palpable just below the umbilicus.

Fetal heartbeats are heard with a fetoscope at 20 weeks’ gestation.

Fetal rebound or ballottement is possible.

Weeks 23 to 27

The umbilicus appears to be level with abdominal skin.

Striae gravidarum are usually apparent.

The uterine fundus is palpable at the umbilicus.

The shape of the uterus changes from globular to ovoid.

Braxton Hicks contractions start.

Weeks 28 to 31

The patient gains 8 to 10 lb (3.5 to 4.5 kg) in the third trimester.

The uterine wall feels soft and yielding.

The uterine fundus is halfway between the umbilicus and xiphoid process.

Fetal outline is palpable.

The fetus is mobile and may be found in any position.

Weeks 32 to 35

The mother may experience heartburn.

Striae gravidarum become more evident.

The uterine fundus is palpable just below the xiphoid process.

Braxton Hicks contractions increase in frequency and intensity.

The mother may experience shortness of breath.

Weeks 36 to 40

The umbilicus protrudes.

Varicosities, if present, become very pronounced.

Ankle edema is evident.

Urinary frequency recurs.

Engagement, or lightening, occurs.

The mucus plug is expelled.

Cervical effacement and dilation begin.

Eyes

Be sure to perform a careful inspection of the eyes. Look for edema in the eyelids. Ask the patient if she ever sees spots before her eyes or has diplopia (double vision) or other vision problems. (See Watching for vision changes.) These assessment findings may indicate gestational hypertension. In addition, an ophthalmoscopic examination may reveal that the optic disk appears swollen from edema associated with gestational hypertension.

Education edge

Education edgeWatching for vision changes

Poor vision can be a danger sign of pregnancy, possibly indicating gestational hypertension. Instruct the pregnant woman to watch for symptoms of poor vision, such as spots in the eyes or double vision, and to report them as soon as possible. If she does close desk work on a regular basis, such as computer work or work with small numbers and lists or charts that require tedious and close attention, advise her to take a break every hour so that work-related eyestrain isn’t confused with actual danger signs.

Nose

Inspect the nose for nasal congestion and nasal membrane swelling, which may result from increased estrogen levels. If these conditions occur, advise the patient to avoid using topical medicines and nose sprays for relief without her health care practitioner’s consent. These medications can be absorbed into the bloodstream and may harm the fetus.

Ears

During early pregnancy, nasal stuffiness may lead to blocked eustachian tubes, which can cause a feeling of “fullness” and dampening of sound. This disappears as the body adjusts to the new estrogen level.

Mouth

Examine the inside and outside of the mouth. Cracked corners may reveal a vitamin A deficiency. Pinpoint lesions with an erythematous base on the lips suggest herpes infection. Gingival (gum) hypertrophy may result from estrogen stimulation during pregnancy; the gums may be slightly swollen and tender to the touch. (See Taking care of the teeth.)

|

Neck

Slight thyroid hypertrophy may occur during pregnancy because overall metabolic rate is increased. Lymph nodes normally aren’t palpable and, if enlarged, may indicate an infection.

Breasts

During pregnancy, the areola may darken, breast size increases, and breasts become firmer. Blue streaking of veins may occur on the breasts. Colostrum may be expressed as

early as 16 weeks’ gestation. Montgomery tubercles may become more prominent.

early as 16 weeks’ gestation. Montgomery tubercles may become more prominent.

Education edge

Education edgeTaking care of the teeth

Advise the patient that dental hygiene and taking care of dental caries are important during pregnancy. Dental X-rays can be taken during pregnancy as long as the woman reminds her dentist that she’s pregnant and needs a lead apron. Extensive dental work requiring anesthesia shouldn’t be done during pregnancy without approval from the woman’s practitioner.

BSE basics

Instruct the patient on how to perform a breast selfexamination (BSE), and tell her to perform a BSE monthly. Also educate her on the ongoing changes she’ll experience during pregnancy, as appropriate.

Heart

Assess the patient’s heart. Heart rate should range from 70 to 80 beats/minute. Occasionally, a benign functional heart murmur that’s caused by increased vascular volume may be auscultated. If this occurs, the patient needs further evaluation to ensure that the condition is only a physiologic change related to the pregnancy and not a previously undetected heart condition.

Lungs

Assess respiratory rate and rhythm. Vital capacity (the amount of air that can be exhaled after maximum inspiration) shouldn’t be reduced despite the fact that lung tissue assumes a more horizontal appearance as the growing uterus pushes up on the diaphragm. Late in pregnancy, diaphragmatic excursion (diaphragm movement) is reduced because the diaphragm can’t descend as fully as usual because of the distended uterus.

|

Back

When examining the patient’s back, be sure to assess for scoliosis. If she has scoliosis, refer her to an orthopedic surgeon to make sure the condition doesn’t worsen during pregnancy. Typically, the lumbar curve is accentuated when standing so the patient can maintain body posture in the face of increasing abdominal size. If she has scoliosis, however, the added pressure of the growing fetus on the back may be more bothersome and painful.

Rectum

Assess the rectum for hemorrhoidal tissue, which commonly results from pelvic pressure that prevents venous return.

Extremities and skin

Assess for palmar erythema, an itchy redness in the palms that occurs early in pregnancy as a result of high estrogen levels. Assess for varicose veins and check the filling time of nail beds. Observe for edema, and assess the patient’s gait. The patient should be taught proper posture and walking to prevent musculoskeletal and gait problems later in pregnancy.

Pelvic examination

A pelvic examination provides information on the health of internal and external reproductive organs and is valuable in assessment.

Patient prep

Take the following steps to prepare the patient for the pelvic examination:

Ask the patient if she has douched within the past 24 hours. Explain that douching can wash away cells and organisms that the examination is designed to evaluate.

For the patient’s comfort, instruct her to empty her bladder before the examination. Provide a urine specimen container, if needed.

To help the patient relax, which is essential for a thorough pelvic examination, explain what the examination entails and why it’s necessary. The patient may desire to have a person in the room with her for support. It may also be beneficial to review some relaxation techniques with the patient such as deep breathing.

If the patient is scheduled for a Papanicolaou (Pap) test, inform her that she may have to return later for another test if the findings of the first test aren’t conclusive. Reassure her that this is done to confirm the results of the first test. If she has never had a Pap test, tell her that the test shouldn’t hurt.

Explain to the patient that a bimanual examination is performed to assess the size and location of the ovaries and uterus.

|

Shall I compare thee?

During the examination, record the patient’s uterine fundal height and fetal heart sounds. Compare the new fundal height findings with the information obtained in the patient’s history. In other words, make sure that the information you obtained about the patient’s last menstrual period and her EDD correlate with the current fundal height.

On the move

At about 12 to 14 weeks’ gestation, the uterus is palpable over the symphysis pubis as a firm globular sphere. It reaches the umbilicus at 20 to 22 weeks, the xiphoid at 36 weeks, and then, in many cases, returns to about 4 cm below the xiphoid due to lightening at 40 weeks. (See Measuring fundal height.)

If the woman is past 12 weeks of pregnancy, palpate fundus location, measure fundal height (from the notch above the symphysis pubis to the superior aspect of the uterine fundus), and plot the height on a graph. This information helps detect variations in

fetal growth. If an abnormality is detected, it can be further investigated with ultrasound to determine the cause.

fetal growth. If an abnormality is detected, it can be further investigated with ultrasound to determine the cause.

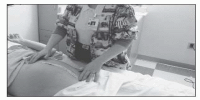

Advice from the experts

Advice from the expertsMeasuring fundal height

Measuring the height of the uterus above the symphysis pubis reflects the progress of fetal growth, provides a gross estimate of the duration of pregnancy, and may indicate intrauterine growth retardation. Excessive increase in fundal height could mean multiple pregnancy or hydramnios (an excess of amniotic fluid).

To measure fundal height, use a pliable (not stretchable) tape measure or pelvimeter to measure from the notch of the symphysis pubis to the top of the fundus, without tipping back the corpus. During the second and third trimesters, make the measurement more precise by using the following calculation, known as McDonald rule:

|

After the examination, offer the patient premoistened tissues to clean the vulva.

|

Estimation of pelvic size

The size and shape of woman’s pelvis can affect her ability to deliver her neonate vaginally. It’s impossible to predict from a woman’s outward appearance if her pelvis is adequate for the passage of a fetus. For example, a woman may look as if she has a wide pelvis, but she may only have a wide iliac crest and a normal, or smaller than normal, internal ring. (See Pelvic shape and potential problems, page 168.)

Clearly clearance counts

Internal pelvic measurements give actual diameters of the inlet and outlet through which the fetus passes. The internal pelvis must be large enough to allow a patient to give birth vaginally without difficulty. Differences in pelvic contour develop mainly because of heredity factors. However, such diseases as rickets may cause contraction of the pelvis, and pelvic injury may also be responsible for pelvic distortion.

Now or later?

Pelvic measurements can be taken at the initial visit or at a visit later in pregnancy, when the woman’s pelvic muscles are more

relaxed. If a routine ultrasound is scheduled, estimations of pelvic size may be made through a combination of pelvimetry and fetal ultrasound.

relaxed. If a routine ultrasound is scheduled, estimations of pelvic size may be made through a combination of pelvimetry and fetal ultrasound.

Pelvic shape and potential problems

The shape of a woman’s pelvis can affect the delivery of her fetus. Her pelvis may be one of four types:

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access