As with any assessment, a postpartum assessment consists of a patient history and a physical examination.

Patient history

Your postpartum patient history should focus on the patient’s pregnancy, labor, and birth events. You should be able to find much of this information on the medical record. For example, the medical record should contain information about:

problems experienced, such as gestational hypertension or gestational diabetes

time of labor onset and admission to the birthing area

types of analgesia and anesthesia used

length of labor

time of delivery

time of placenta expulsion and appearance of the placenta

sex, weight, and status of the neonate.

You’ll need this information to plan the mother’s care and promote maternal-neonate bonding.

Another reliable source

Don’t rely on the medical record as your sole source of information. Always ask the mother to describe the events and fill in the details in her own words. This is also a good way to find out her emotions and feelings about pregnancy and childbirth.

Also ask the mother about her family and lifestyle, including support systems, other children, other people living in the home, her occupation, her community environment, and her socioeconomic level. This information can help you determine whether additional support, follow-up, or education about self-care and neonatal care are needed.

Physical examination

In many cases, you won’t need to do a complete physical examination in the postpartum period because the mother already had a complete assessment early in the labor process. However, you should complete a review of systems, covering the following areas:

general appearance

skin

energy level, including level of activity and fatigue

pain, including location, severity, and aggravating factors, such as sitting and walking

gastrointestinal (GI) elimination, including bowel sounds, passage of flatus, and hemorrhoids

fluid intake

urinary elimination, including the time and amount of first voiding

peripheral circulation.

In addition, you’ll need to assess these four critical areas:

breasts

uterus

lochia

perineum

Breasts

Inspect and then palpate the breasts, noting size, shape, and color. At first, the breasts should feel soft and secrete a thin, yellow fluid called

colostrum. However, as they fill with milk—usually around the third post-partum day—they should begin to feel firm and warm. Between feedings, the entire breast may be tender, hard, and tense on palpation. A low-grade temperature (under 101° F [38.3° C]) isn’t uncommon between days 2 and 5, but it shouldn’t last for more than 24 hours. (See

Engorgement or something else? page 430.)

Land of nodule

A small, firm nodule in the breast may be caused by a temporarily blocked milk duct or milk that hasn’t flowed forward into the nipple. This problem generally corrects itself when the neonate breast-feeds. Be sure to reassess the breast after the neonate feeds to determine if the problem has resolved, and report your findings—including the location of the nodule—to the practitioner.

Inspect the nipples for cracks, fissures, or configuration. Cracks or breaks in the skin can provide an entry for organisms and lead to infection. Also look for other problems. Successful breast-feeding can be more challenging if the nipples are flat or inverted. A lactation consultant or a breast-feeding counselor may be helpful.

Uterus

During your examination, palpate the uterine fundus to determine uterine size, degree of firmness, and rate of descent, which is measured in fingerbreadths

above or below the umbilicus. Unless the practitioner orders otherwise, perform fundal assessments every 15 minutes for the first hour after delivery, every 30 minutes for the next hour or two, every 4 hours for the rest of the first postpartum day, and then every shift until the patient is discharged. Fundal assessment will need to occur more frequently if complications are noted.

Pain at the incision site makes fundal assessment especially uncomfortable for the patient who has had a cesarean birth. In such cases, provide pain medication beforehand as ordered.

Ready, set, palpate!

Before palpating the uterus, explain the procedure to the patient and provide privacy. Wash your hands and then put on gloves. Also, ask the patient to void. A full bladder makes the uterus boggier and deviates the fundus to the right of the umbilicus or + 1 or + 2 above the umbilicus. When the bladder is empty, the uterus should be at or close to the level of the umbilicus.

Next, lower the head of the bed until the patient is lying supine or with her head slightly elevated. Expose the abdomen for palpation and the perineum for inspection. Watch for bleeding, clots, and tissue expulsion while massaging the uterus.

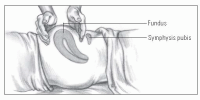

Performing palpation

To palpate the uterine fundus, follow these steps:

While supporting the lower segment of the uterus with a hand placed just above the symphysis, gently palpate the fundus with your other hand to evaluate its firmness. (See

Feeling the fundus.)

Note the level of the fundus above or below the umbilicus in centimeters or fingerbreadths.

If the uterus seems soft and boggy, gently massage the fundus with a circular motion until it becomes firm. Without digging into the abdomen, gently compress and release your fingers, always supporting the lower uterine segment with your other hand. Observe the vaginal drainage during massage.

Massage long enough to produce firmness but not discomfort. You may also encourage the patient to massage her fundus for 10 to 15 seconds every 15 minutes. This is usually necessary only for a few hours.

Notify the practitioner immediately if the uterus fails to contract and heavy bleeding occurs. If the fundus becomes firm after massage, keep one hand on the lower uterus and press gently toward the pubis to expel clots. (See

Complications of fundal palpation.)

Remember the bladder

When assessing the uterine fundus, also assess for bladder distention. A distended bladder can impede the downward descent of the uterus by pushing it upward and, possibly, to the right side. If the bladder is distended and the patient is unable to urinate, you may need to catheterize her.

Lochia

After birth, the outermost layer of the uterus becomes necrotic and is expelled. This vaginal discharge—called

lochia—is similar to menstrual flow and consists of blood, fragments of the decidua, white blood cells (WBCs), mucus, and some bacteria.

Assessing lochia flow

Help the patient into the lateral Sims position. Be sure to check under the patient’s buttocks to make sure that blood isn’t pooling there. Then, remove the patient’s perineal pad and evaluate the character, amount, color, odor, and consistency (presence of clots) of the discharge. Before removing the perineal pad, make sure that it isn’t sticking to any perineal stitches. Otherwise, tearing may occur, possibly increasing the risk of bleeding.

On the lookout

Here’s what to look for when assessing lochia:

Amount— Although it varies, the amount of lochia is typically comparable to the amount during menstrual flow. A woman who’s breast-feeding may have less lochia. Also, a woman who has had a cesarean birth may have a scant amount of lochia; however, lochia shouldn’t be absent. Lochia should be present for at least 3 weeks postpartum. Lochia flow increases with activity; for example, when the patient gets out of bed the first several times (due to pooled lochia being released) or when she lifts a heavy object or walks up stairs (due to an actual increase in the amount of lochia). If your patient saturates a perineal pad in less than an hour, this is considered excessive flow, and you should notify the practitioner.

Color— Lochia typically is described as lochia rubra, serosa, or alba, depending on the color of the discharge. Lochia color depends on the postpartum day. A sudden change in color— for example, from pink back to red—suggests new bleeding or retained placental fragments.

Odor— Lochia should smell similar to menstrual flow. A foul or offensive odor suggests infection.

Consistency— Lochia should have minimal or small clots, if any. Evidence of large or numerous clots indicates poor uterine contraction and requires further assessment.

Perineum and rectum

The pressure exerted on the perineum and rectum during birth results in edema and generalized tenderness. Some areas of the

perineum may be ecchymotic, caused by the rupture of surface capillaries. Sutures from an episiotomy or laceration may also be present. Hemorrhoids are also commonly seen.

What’s your position?

Assessment of the perineum and rectum mainly involves inspection and is performed at the same time that you assess the lochia. Help the patient into the lateral Sims position. This position provides better visibility and causes less discomfort for the patient with a mediolateral episiotomy. A back-lying position can also be used for patients with midline episiotomies. Make sure you have adequate light for inspection.

Education edge

Education edge Memory jogger

Memory jogger Education edge

Education edge Advice from the experts

Advice from the experts Education edge

Education edge Memory jogger

Memory jogger