Artificial airway options include nasotracheal, orotracheal, and tracheostomy. Endotracheal (ET) and tracheostomy tubes are available in several sizes, cuffed and uncuffed, for the pediatric population.

Several methods are available to determine the appropriate size, such as: ET tube size = age in years + 16 divided by 4 (consult facility policy).

The patient should be closely monitored for hypoxia and bradycardia during intubation.

Only experienced and highly trained and skilled practitioners should perform intubation.

Resuscitation and reintubation equipment, access to oxygen and suction equipment must always be readily available.

An appropriate-size self-inflating bag with reservoir for oxygenation and mask should remain with the patient.

Action should be taken to prevent dislodgement of the artificial airway (especially during movement of the child) and obstruction of the airway.

Pediatric ET tubes have small diameters and are easily obstructed by thick secretions.

Adequate humidification will loosen secretions and suctioning will prevent airway obstruction.

Frequent vital signs and respiratory assessments are necessary. Cardiorespiratory monitors, pulse oximeter, endtidal carbon dioxide, or transcutaneous carbon dioxide monitors are also necessary.

PROCEDURE GUIDELINES 44-1

Oxygen Therapy for Children

PROCEDURE

Nursing Action

Rationale

Explain the procedure to the child and allow the child to feel the equipment and the oxygen flowing through the tube and mask.

Maintain a clear airway by suctioning, if necessary.

Provide a source of humidification.

Measure oxygen concentrations every 1-2 hours when a child is receiving oxygen through incubator hood.

Measure when the oxygen environment is closed.

Measure the concentration close to the child’s airway.

Record oxygen concentrations and simultaneous measurements of the pulse and respirations.

Observe the child’s response to oxygen.

Organize nursing care so interruption of therapy is minimal.

Periodically check all equipment during each span of duty.

Clean equipment daily and change it at least once per week. (Tubing and nebulizer jars should be changed daily.)

Keep combustible materials and potential sources of fire away from oxygen equipment.

Avoid using oil or grease around oxygen connections.

Avoid the use of wool blankets and those made from some synthetic fibers.

Prohibit smoking in areas where oxygen is being used.

Have a fire extinguisher available.

Avoid lengthy oxygen tubing in any young child that is not being constantly supervised.

Terminate oxygen therapy gradually.

Slowly reduce litre flow.

Open air vents in incubators.

Continually monitor the child’s response during weaning. Observe for restlessness, increased pulse rate, respiratory distress, and cyanosis.

The child will be reassured if he or she understands the procedure and knows what to expect.

The delivery of oxygen requires a clear airway.

Oxygen is a dry gas and requires the addition of moisture to prevent drying of the tracheobronchial tree and thickening and consolidating secretions.

It is desirable to keep the oxygen concentration as low as possible while still providing for physiologic requirements. This minimizes the child’s risk of developing retinopathy of prematurity. (Desired oxygen concentrations are determined by the arterial oxygen tension measurement.) The oxygen analyzer should be calibrated daily on both room air and 100% oxygen. The concentration of oxygen within the space is determined by litre flow, efficiency of the equipment, and frequency with which it is opened to the external environment.

Desired response includes:

Decreased restlessness.

Decreased respiratory distress.

Improved color.

Improved vital sign values.

Interruption of therapy may result in the return of anoxia and defeats the goals of therapy.

For optimal functioning, the equipment should be clean, undamaged, and in good working order.

Unclean equipment may be a source of contamination.

Oxygen supports combustion.

a. Are easily combustible.

b. May cause injury due to static electricity.

c. Limits the risk of fire.

e. May be at risk for injury including strangulation in active children.

Allows the child to adjust to normal atmospheric oxygen concentrations.

These are indications that the child is unable to tolerate reduced oxygen concentration.

Oxygen by nasal cannula or catheter

Refer to Procedure Guidelines 10-12, page 239.

Nasal cannulas are available in a variety of sizes for neonates, infants, and children.

Low-flow meters are available to titrate oxygen at levels under 1 L/minute.

3. Lower flow rate may be necessary for infants.

Oxygen by mask

Choose an appropriate-size mask that covers the mouth and nose of the child but not the eyes.

Use a mask that is capable of delivering the desired oxygen concentration.

Place the mask over the child’s mouth and nose so it fits securely. Secure the mask with an elastic head grip.

Remove the oxygen mask at hourly intervals; wash and dry the face.

Do not use masks for comatose infants or children.

For additional information, refer to Procedure Guidelines 10-14, page 242, and Procedure Guidelines 10-13, page 240.

Extra space under mask and around face is added dead space and decreases effectiveness of the therapy.

Venturi masks for pediatric use deliver low to moderate concentrations of oxygen: 24%, 28%, 31%, 35%, or 40%.

Make sure the mask is adjusted properly over the mouth and nose. Do not allow the oxygen to blow in the child’s eyes.

Makes the patient feel more comfortable.

Such children are more likely to vomit. The risk of aspiration may be increased with mask therapy because of obstruction of the flow of vomitus.

Face tent

Face tents are available in adult size only. They can be used effectively in pediatric patients if inverted to create a smaller reservoir and better fit.

A flow of 8-10 L/minute should be used to flush the system and provide a stable oxygen concentration.

Face tents combine the positive qualities of aerosol masks and mist tents. The child is accessible and may continue to play without feeling confined.

Larger children will require higher flows.

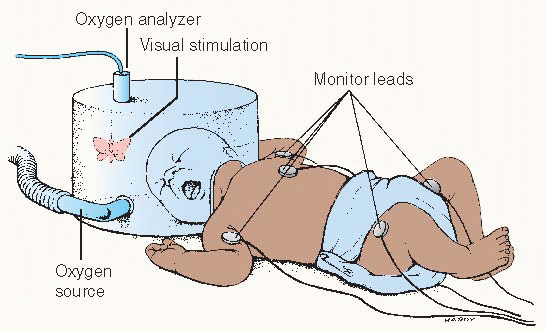

A child receiving humidity and oxygen by way of an aerosol face tent.

A child receiving humidity and oxygen by way of an aerosol face tent.

T-Bars and tracheostomy masks

These devices are used to deliver oxygen to intubated patients.

The flow rate must be set to meet the minute volume requirements of the child and to provide a 100% source of gas.

2. T-bars require a short, flexible tube on the distal end to act as a reservoir and prevent room-air entrapment.

Closed incubator and Isolettes

The incubator is used to provide a controlled environment for the neonate.

Adjust the oxygen flow to achieve the desired oxygen concentration.

An oxygen limiter prevents the oxygen concentration inside the incubator from exceeding 40%.

Higher concentrations (up to 85%) may be obtained by placing the red reminder flag in the vertical position.

Secure a nebulizer to the inside wall of the incubator if mist therapy is desired.

Keep sleeves of incubator closed to prevent loss of oxygen.

Periodically analyze the incubator atmosphere.

Drain and fill reservoirs with sterile water at least every 24 hours.

The unit is able to provide precise environmental control of temperature, oxygen, humidity, and isolation.

Follow manufacturer’s instructions for each make of incubator.

This is desirable because it reduces the hazard of the child’s developing retinopathy of prematurity.

This operates by reducing the air intake.

This should be cleaned and autoclaved daily. Sterile solutions are used to keep the bacteria count at a minimum.

When the incubator or sleeves are opened, supply supplemental oxygen with oxygen mask to face and nose.

Be certain the child is receiving the desired concentration of oxygen.

Decreases risk of Pseudomonas contamination.

Oxygen hood/box

Warmed, humidified oxygen is supplied through a plastic container that fits over the child’s head. This method is more suitable for a child under 1 year of age.

Continuously monitor the oxygen concentration, temperature, and humidity inside the hood.

Open the hood or remove the baby from it as infrequently as possible.

Several different designs are available for use. The manufacturer’s directions should be carefully followed.

This is especially useful when high concentrations of oxygen are desired. The hood may be used in an incubator or with a warming unit.

Oxygen should not be allowed to blow directly into the infant’s face.

Oxygen should be warmed to 87.8°-93.2° F (31°-34° C) to prevent a neonatal response to cold stress, including oxygen deprivation, metabolic acidosis, rapid depletion of glycogen stores, and reduction of blood glucose levels.

Prevents fluctuations of heat and oxygen, which may further debilitate the young infant.

This is a safety consideration.

Evidence Base Ghuman, A. K., Newth, C. J. L., & Khemani, R. G. (2010). Respiratory support in children. Paediatrics and Child Health, 21, 4.

Evidence Base Ghuman, A. K., Newth, C. J. L., & Khemani, R. G. (2010). Respiratory support in children. Paediatrics and Child Health, 21, 4.

Nursing care should continue to address issues of hydration, nutrition, sedation, skin integrity, tissue perfusion, infection control, communication, safety, and parental support and education.

Available ventilators for pediatric use have a wide range of capabilities, versatility, and clinical application. Some are more suitable for use with infants, others with older children.

Nurses must be well acquainted with the characteristics of the particular machine being used and the meaning of the settings and alarms on the machine.

In infants, inspired concentrations of oxygen should always be kept as low as possible (while still providing for physiologic requirements) to prevent the development of retinopathy of prematurity or pulmonary oxygen toxicity.

The oxygen concentration should be checked periodically with an analyzer.

Blood gas analysis to monitor oxygenation, via arteriopuncture or umbilical or arterial lines.

The arterialized capillary sample method is inaccurate for infants in respiratory distress because the constricted peripheral circulation may not reflect the ABG (arterial blood gases) levels accurately.

Ventilator tubing should be changed every 24 hours.

Routine cultures should be taken after intubation; there should be daily Gram staining of secretions.

Suctioning requires aseptic technique.

Special frames are available to support ventilator tubing; this helps to prevent accidental decannulation in infants and small children.

Infants may require support or padding on either side and at the top of their heads to decrease mobility and take up space between the head and the frame.

Pressure gauges should be checked at frequent intervals because this gives an indication of changing compliance or increased airway resistance.

Volume measurements are difficult to obtain in infants because most spirometers incorporated into ventilators and meters do not read accurately at low volumes and flows. However, they are helpful with older children.

Measure respiratory rates of the machine and the patient at least every hour and record.

Table 44-1 Common Pediatric Respiratory Infections | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Observe the respiratory rate and pattern. Count the respirations for 1 full minute, document and note level of activity, such as awake or asleep. Determine if the rate is appropriate for age (see page 1388).

Observe respiratory rhythm and depth. Rhythm is described as regular, irregular, or periodic. Depth is normal, hypopnea or too shallow, hyperpnea or too deep.

Auscultate breath sounds for a full cycle of inspiration and expiration over all lung fields. Note airflow and presence of adventitious sounds such as crackles, wheeze, or stridor.

Observe degree of respiratory effort—normal, difficult, or labored. Normal breathing is effortless and easy.

Document character of dyspnea or labored breathing; continuous, intermittent, worsening, or sudden onset. Note relation to activity, such as rest, exertion, crying, feeding, and association with pain, positioning, or orthopnea.

Note presence of additional signs of respiratory distress: nasal flaring, grunting, and retractions. Note location of retractions (see Figure 44-2) and character (mild, moderate, or severe).

Observe for head bobbing, usually noted in a sleeping or exhausted infant. The infant is held by caregiver with head supported on the caregiver’s arm at the suboccipital area. The head bobs forward with each inspiration.

Observe the child’s color. Note the presence and location of cyanosis—peripheral, perioral, facial, and trunk. Note degree of color changes, duration, and association with activity such as crying, feeding, and sleeping.

Observe the presence of cough, noting type and duration, such as dry, barking, paroxysmal, or productive. Note any pattern, such as time of day or night, association with activity, physical exertion, or feeding. Severity of croup may be determined by cough and signs of respiratory effort.

Mild croup—occasional barking cough, no audible stridor at rest, and either mild or no suprasternal or intercostal retractions.

Moderate croup—frequent barking cough, easily audible stridor at rest, and suprasternal and sternal retractions at rest, but little or no agitation.

Severe croup—frequent barking cough, prominent inspiratory and occasional expiratory stridor, marked sternal retractions, and agitation and distress.

Impending respiratory failure—barking cough (often not prominent), audible stridor at rest (may be hard to hear), sternal retractions (may be marked), lethargy or decreased level of consciousness, and often dusky appearance in the absence of supplemental oxygen.

Note the presence of sputum, including color, amount, consistency, and frequency.

Observe the child’s fingernails and toenails for cyanosis and the presence and degree of clubbing, which indicate underlying chronic respiratory disease.

Evaluate the child’s degree of restlessness, apprehension, and muscle tone.

Note the presence or complaint of chest pain and its location, whether it is local or generalized, dull or sharp, and associated with respiration or grunting.

Assess for signs of infection, such as elevated temperature; enlarged cervical lymph glands; purulent discharge from nose or ears; sputum; or inflamed mucous membranes.

Ineffective Airway Clearance related to inflammation, obstruction, secretions, or pain.

Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to inflammatory process or pain.

Deficient Fluid Volume related to fever, decreased appetite, and vomiting.

Fatigue related to increased work of breathing.

Anxiety related to respiratory distress and hospitalization.

Parental Role Conflict related to hospitalization of the child.

Provide a humidified environment enriched with oxygen to combat hypoxia and to liquify secretions (see Procedure Guidelines 44-1, pages 1480 to 1482).

Advise the parents to use a jet or ultrasonic nebulizer at home and encourage fluids, as tolerated.

Keep nasal passages free of secretions. Infants are obligate nose breathers. Use a bulb syringe to clear nares and oropharynx.

Place the child in a comfortable position to promote easier ventilation.

Semi-Fowler’s—use infant seat or elevate head of bed.

Occasional side or abdominal position will aid drainage of liquefied secretions. Do not place infant in prone position.

Do not position the child in severe respiratory distress in a supine position. Allow the child to assume a position of comfort.

Provide measures to improve ventilation of the affected portion of the lung.

Change position frequently.

Provide postural drainage, if prescribed.

Relieve nasal obstruction that contributes to breathing difficulty. Instill normal saline solution or prescribed nose drops and apply nasal suctioning.

Quiet prolonged crying, which can irritate the airway, by soothing the child; however, crying may be an effective way to inflate the lungs.

Realize that coughing is a normal tracheobronchial cleansing procedure, but temporarily relieve coughing by allowing the child to sip water; use extreme caution to prevent aspiration.

Insert a nasogastric tube, as ordered, to relieve abdominal distention, which can limit diaphragmatic excursion.

Ensure that the child’s oxygen input is not compromised.

Monitor oxygen saturations, as indicated; pulse oximetry should be performed if hypoxia is suspected.

If compressed air or oxygen is administered, use a head box to avoid excess carbon dioxide concentrations and increased respiratory rate.

Administer appropriate antibiotic or antiviral therapy.

Observe for drug sensitivity.

Observe the child’s response to therapy.

Administer specific treatment for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), if ordered.

There is presently no evidence that supports the use of ribavirin or inhaled corticosteroids in acute bronchiolitis; however, some health care providers do consider these options in the management of RSV.

If the decision is made to initiate ribavirin therapy, appropriate precautions should be implemented to protect personnel and caregivers.

Information should be provided about the potential but unknown risk of exposure to ribavirin.

Pregnant women should be advised to refrain from providing direct care to patients who are receiving ribavirin therapy.

Methods to reduce environmental exposure to ribavirin should be employed:

Stop aerosol administration before opening hood or tent.

Use room with adequate ventilation of at least six air exchanges per hour.

Consider the use of scavenger devices to help decrease the escape of ribavirin into the air.

Staff should wear aprons and face masks for the duration of the time the nebulizer is in use.

For cases of severe respiratory distress, assist with intubation or tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation.

Tracheostomy and endotracheal tubes are generally not cuffed for infants and small children because the tube itself is big enough relative to the size of the trachea to act as its own sealer.

Position the infant with a tracheostomy with the neck extended by placing a small roll under the shoulders to prevent occlusion of the tube by the chin. Support his or her head and neck carefully when moving the infant to prevent dislodgement of the tube.

When feeding, cover the tracheostomy with a moist piece of gauze, or use a bib for older infants or young children.

See page 1479 in this chapter as well as Chapter 10 for care of the patient on mechanical ventilation.

Administer fluids via intravenous (IV) route at the prescribed rate.

To prevent aspiration, withhold oral food and fluids if the child is in severe respiratory distress.

Offer the child small sips of clear fluid when respiratory status improves.

Note any vomiting or abdominal distention after the oral fluid is given.

As the child begins to take more fluid by mouth, notify the health care provider and modify the IV fluid rate to prevent fluid overload.

Do not force the child to take fluids orally because this may cause increased distress and possibly vomiting. Anorexia will subside as the condition improves.

Assist in the control of fever to reduce respiratory rate and fluid loss.

Give antipyretics, as prescribed.

Record the child’s intake and output and monitor urinespecific gravity.

Provide mouth care or offer mouth rinse if child is able to perform this safely.

Disturb the child as little as possible by organizing nursing care, and protect the child from unnecessary interruptions.

Be aware of the age of the child and be familiar with the level of growth and development as it applies to hospitalization.

Encourage the parents to stay with the child as much as possible to provide comfort and security.

Provide opportunities for quiet play as the child’s condition improves.

Explain procedures and hospital routine to the child as appropriate for age.

Provide a quiet, stress-free environment.

Observe the child’s response to the oxygen therapy environment and provide reassurance.

The child may experience fear of confinement or suffocation.

Vision is distorted through the plastic.

The environment is noisy and damp.

Physical and diversional activities are restricted.

Parental contact is decreased.

The environment is often uncomfortable.

Avoid the use of sedatives and opiates, which may obscure restlessness. Restlessness is a sign of increasing respiratory distress or obstruction.

Allow the child to assume a position of comfort.

Help the parents understand the purpose of the oxygen therapy/humidifier and how to work with it.

Discuss their fears and concerns about the child’s therapy.

Include the parents in planning for the child’s care. Promote their participation in caring for the child.

Recognize that the parents will need rest periods. Encourage them to take breaks and eat on a regular basis.

Teach the importance of good hygiene. Include information on handwashing and appropriate ways to handle respiratory secretions at home.

Teach the family when it is appropriate to keep the child home from school (any fever, coughing up secretions, and significant runny nose in toddler or younger child).

Teach methods to keep the ill child well hydrated.

Provide small amounts of fluids frequently.

Offer clear liquids and prepared electrolyte preparations.

Offer frozen juice pops.

Avoid juices with a high sugar content.

Teach ways to assess the child’s hydration status at home.

Decreased number of wet diapers or number of times the child urinates per day.

Decreased activity level.

Dry lips and mucous membranes.

No tears when the child cries.

Teach the parents when to contact their health care provider—signs of respiratory distress, recurrent fever, decreased appetite and activity, and signs of dehydration.

Teach about medications and follow-up.

If a tracheostomy was required, teach care of the tracheostomy, use of equipment, safety, and referral for home nursing care before discharge.

Breath sounds clear and equal.

Easy, regular, unlabored respirations on room air (or back to baseline if the child is on oxygen).

Mucous membranes moist; urine output adequate.

Bathing and feeding tolerated well.

Child calm and interacts appropriately with family and staff.

Parents participate in the child’s care.

Evidence Base

Evidence Base

They are a first line of defense against respiratory infections.

Because the growth of the tonsils and adenoids in the first 10 years of life exceeds general somatic growth, these structures appear especially large in the child.

The natural process of involution of tonsillar and adenoidal lymphoid tissue in the prepubertal years is associated with decreased frequency of throat and ear infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

NURSING ALERT Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine provides protection from 23 types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is recommended for children age 2 years and older with sickle cell disease, functional or anatomic asplenia, nephrotic syndrome, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and Hodgkin’s disease before beginning cytoreduction therapy.

NURSING ALERT Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine provides protection from 23 types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is recommended for children age 2 years and older with sickle cell disease, functional or anatomic asplenia, nephrotic syndrome, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and Hodgkin’s disease before beginning cytoreduction therapy. NURSING ALERT Pentamidine is associated with a high incidence of adverse reactions: pancreatitis, renal dysfunction, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, hypotension, fever, and neutropenia. Pentamidine should not be used with didanosine, which also causes pancreatitis, and in patients with hepatic dysfunction.

NURSING ALERT Pentamidine is associated with a high incidence of adverse reactions: pancreatitis, renal dysfunction, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, hypotension, fever, and neutropenia. Pentamidine should not be used with didanosine, which also causes pancreatitis, and in patients with hepatic dysfunction. NURSING ALERT If ABG analysis is done, a normal partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide may not indicate decreased severity. By the time hypercapnia is seen, intubation will be required.

NURSING ALERT If ABG analysis is done, a normal partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide may not indicate decreased severity. By the time hypercapnia is seen, intubation will be required. NURSING ALERT Do not attempt to visualize the epiglottis with a tongue blade or take a throat culture. May cause laryngospasm and airway obstruction.

NURSING ALERT Do not attempt to visualize the epiglottis with a tongue blade or take a throat culture. May cause laryngospasm and airway obstruction.