Pediatric Oncology

PEDIATRIC ONCOLOGIC DISORDERS

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseNational Cancer Institute. (2011). A snapshot of pediatric cancer. Bethesda, MD: Author. Available: www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/servingpeople/snapshots/pediatric.pdf.

Cancer is the leading cause of death from disease in children ages 1 to 14. It affects approximately 1 to 2 out of 10,000 children annually in the United States. The incidence of specific cancers is related to age, gender, and ethnic background.

Common types of cancer in children (in order of frequency) include leukemia, central nervous system (CNS) cancers, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, Wilms’ tumor, bone cancer, and retinoblastoma. Treatment modalities include surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, blood and marrow transplant, immunotherapy, and gene therapy (see Chapter 8, page 134). See Chapter 43 for general nursing care of the sick or hospitalized child.

Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseMeenaghan, T., Dowling, M., & Kelly, M. (2012). Acute leukemia: making sense of a complex blood disorder. British Journal of Nursing, 21(2), 76-83.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is a primary disorder of the bone marrow in which the normal marrow elements are replaced by immature or undifferentiated blast cells. When the quantity of normal marrow is depleted below the level necessary to maintain peripheral blood elements within normal ranges, anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia occur. ALL is the most common malignancy in children, occurring in 3 to 4 out of 100,000 children younger than age 15. It is more common among white and Hispanic children and is more common in boys than in girls.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The exact cause of ALL is unknown.

Environmental factors, including viral agents, as well as genetic factors and chromosomal abnormalities are suspected in some cases.

ALL results from the growth of an abnormal type of nongranular, fragile leukocyte in the blood-forming tissues, particularly in the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes.

The abnormal lymphoblast has little cytoplasm and a round, homogeneous nucleus (see Figure 51-1, page 1680).

ALL is classified according to the cell type involved: T lymphoblasic leukemia or B lymphoblastic leukemia.

Normal bone marrow elements may be displaced or replaced in this type of leukemia.

The changes in the blood and bone marrow result from the accumulation of leukemic cells and from the deficiency of normal cells.

Red blood cell (RBC) precursors and megakaryocytes from which platelets are formed are decreased, causing anemia, prolonged and unusual bleeding, tendency to bruise easily, and petechiae.

Normal white blood cells (WBCs) are significantly decreased, predisposing the child to infection.

The bone marrow is hyperplastic, with a uniform appearance caused by leukemic cells.

Leukemic cells may infiltrate into lymph nodes, spleen, and liver, causing diffuse adenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

Expansion of marrow or infiltration of leukemic cells into bone causes bone and joint pain.

Invasion of the CNS by leukemic cells may cause headache, vomiting, cranial nerve palsies, convulsions, coma, papilledema, and blurred or double vision.

Weight loss, muscle wasting, and fatigue may occur when the body cells are deprived of nutrients because of the immense metabolic needs of the proliferating leukemic cells.

Clinical Manifestations

Manifestations depend on the degree to which the bone marrow has been compromised and the location and extent of extramedullary infiltration.

Presenting symptoms:

Fatigability.

General malaise, listlessness.

Persistent fever of unknown cause.

Recurrent infection.

Petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses after minor trauma.

Pallor.

Generalized lymphadenopathy.

Abdominal pain caused by organomegaly.

Bone and joint pain.

Headache and vomiting (with CNS involvement).

Presenting symptoms may be isolated or in any combination or sequence.

Diagnostic Evaluation

May have altered peripheral blood counts. Blood studies may show the following:

Low hemoglobin level, RBC count, hematocrit, and platelet count.

Decreased, elevated, or normal WBC count.

Bone marrow examination and stained peripheral smear examination show large numbers of lymphoblasts and lymphocytes.

Lumbar puncture to assess for lymphoblasts in CNS to determine CNS involvement.

Renal and liver function studies determine contraindications or precautions for chemotherapy.

Chest x-ray determines whether a mediastinal mass or pneumonia is present.

Varicella and cytomegalovirus titer determine risk of infection.

The CNS and testes are sites of “sanctuary”; CNS treatment and surveillance is standard and testes are evaluated with physical examinations.

Management

Supportive therapy is indicated to control such disease complications as hyperuricemia, electrolyte imbalance, infection, anemia, bleeding, pain, nausea/vomiting, and fatigue.

Specific therapy is warranted to eradicate malignant cells and to restore normal marrow function.

Chemotherapy is used to achieve complete remission, with restoration of normal peripheral blood and physical findings; it is administered through an indwelling central catheter or implantable port. See Table 51-1.

Although no universally accepted standard therapy for the treatment of children with ALL exists, most facilities have similar protocols that use a combination of drugs.

Components of therapy:

Induction, the initial course of therapy designed to achieve complete remission, usually includes a combination of vincristine, L-asparaginase, and corticosteroids. A fourth drug, such as daunorubicin, doxorubicin, or cytosine arabinoside, may be added.

CNS prophylaxis generally consists of intrathecal administration of methotrexate alone or in combination with hydrocortisone and cytarabine. Craniospinal irradiation may also be used to treat CNS disease.

Consolidation treatment, a period of intensified treatment immediately after remission induction, attempts total eradication of leukemic cells. It usually includes a combination of methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, etoposide, cytosine arabinoside, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, vincristine, L-asparaginase, and doxorubicin or daunorubicin.

Maintenance or continuation therapy prevents reappearance of the disease (usually continued for approximately 2½ to 3 years; boys require longer maintenance therapy to prevent testicular relapse). It usually includes daily oral administration of 6-mercaptopurine and weekly oral or I.M. administration of methotrexate with intermittent administration of other drugs, such as vincristine, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cytosine arabinoside, or daunorubicin.

Reinduction therapy induces remission if relapse occurs and usually includes the same initial drugs. Sometimes, however, additional agents may be added.

If testicular relapse occurs, radiation therapy to the testicles is administered.

Current standards of treatment are designed on risk-based criteria; patients with worse prognostic indicators receive more intensive therapy.

Blood and marrow transplantation has been used successfully to treat children who fail to respond to conventional treatment.

Table 51-1 Commonly Used Chemotherapeutic Agents to Treat Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERTAssess patient and monitor vital signs after administration of L-asparaginase-type drugs for signs of anaphylaxis. Have emergency drugs and equipment at the bedside (oxygen, epinephrine, antihistamines, and steroids). If administering in the outpatient setting, observe patients for at least 1 hour.

Prognosis

At least 98% of children with ALL can be expected to achieve an initial remission if treated in a specialized facility.

Overall 5-year survival is 90%.

The prognosis becomes poorer with each relapse the child experiences.

Relapse is rare after 7 years from diagnosis.

Factors associated with prognosis:

Initial WBC count (WBC count >50,000 has worse prognosis).

Age (younger than age 2 and older than age 10 have poorer prognosis, and infants younger than age 1 have even worse prognosis).

Extramedullary involvement (poorer prognosis).

Type of leukemia cytogenetic factors and immunophenotype (DNA index, karyotype).

Complications

Infection—most frequently occurs in the blood, lungs, GI tract, or skin. Patients with central lines are at increased risk.

Hemorrhage—usually caused by thrombocytopenia.

CNS involvement.

Bony involvement.

Testicular involvement.

Urate nephropathy (rarely seen except in induction).

Acute complications of treatment (eg, cardiomyopathy).

Late effects of treatment (treatment-specific). Most frequent long-term complication is neurocognitive dysfunction causing school difficulty.

Nursing Assessment

Obtain a history.

When taking the history, focus on symptoms that led to the diagnosis and previous symptoms for the past 2 weeks. For example, inquire about fatigue, headache, nausea, vomiting, pallor, bleeding, pain, or fever.

Ask about past history of varicella zoster infection (chickenpox), which could lead to disseminated infection if acquired during immunosuppression. Also ask about recent exposures, including sibling exposures.

Perform a physical examination, including:

Examination of skin for petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses.

Palpation of lymph nodes for enlargement, tenderness, and mobility.

Palpation of spleen and liver for enlargement.

Examination of fundi to detect papilledema with CNS disease.

Inspection of skin for areas of infection, including indwelling catheter sites.

Auscultation of lungs for crackles or rhonchi, indicative of pneumonia.

Temperature for fever.

Assess family coping mechanisms and use of resources such as support systems.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTReport changes in behavior or personality, persistent nausea, vomiting, headache, lethargy, irritability, dizziness, ataxia, convulsions, or alterations in state of consciousness. These may be signs of CNS disease or relapse. CNS relapse is usually caught on routine screening.

Nursing Diagnoses

Anxiety of parents related to learning of diagnosis.

Risk for Infection and hemorrhage related to bone marrow suppression caused by chemotherapy and disease.

Disturbed Body Image related to alopecia associated with chemotherapy.

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements related to anemia, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and mucosal ulceration secondary to chemotherapy or radiation.

Acute Pain related to diagnostic procedures, progression of the disease, and adverse effects of treatment.

Activity Intolerance related to fatigue that results from the disease and treatment.

Anxiety of child related to hospitalization and diagnostic and treatment procedures.

Nursing Interventions

Decreasing Parental Anxiety

Be available to the parents when they want to discuss their feelings.

Offer kindness, concern, consideration, and sincerity toward the child and parents; be a source of consolation.

Contact the family’s clergyman or the hospital chaplain.

Obtain the services of a social worker, as appropriate, to help the family use appropriate community resources.

Offer hope that therapy will be effective and will prolong life.

Have parents speak with parents of a child currently on therapy.

Encourage parents to participate in activities of daily living to help them feel a part of their child’s care.

Assess family dynamics and coping mechanisms and plan interventions accordingly.

Help the parents to deal with anticipatory grief.

Help the parents to deal with other family members and friends.

Encourage the parents to discuss concerns about limiting their child’s activities, protecting child from infection, disciplining child, and having anxieties about the illness.

Facilitate communication with the clinic nurse or clinical specialist who may interact with the child during the entire course of illness.

Encourage parents to continue established family patterns, including school attendance, social life, and family activities, as medically indicated.

Preventing Infection and Hemorrhage

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAlexander, S., Nieder, M., Zerr, D., et al. (2012). Prevention of bacterial infection in pediatric oncology: What do we know, what can we learn? Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 59(1), pp. 16-20.

Monitor complete blood count (CBC), as ordered.

Provide adequate hydration.

Maintain parenteral fluid administration.

Offer small amounts of oral fluids, if tolerated.

Observe renal function carefully.

Measure and record urine output.

Check specific gravity.

Observe the urine for evidence of gross bleeding.

Use labsticks to determine if occult urinary bleeding is present.

Protect the child from infection sources.

Never use a rectal thermometer, suppositories, or enemas when caring for a neutropenic patient.

Family, friends, personnel, and other patients who have infections should not visit or care for the child. Discuss care of siblings while child is on therapy.

Private rooms are preferred, but if it is necessary to share, do not place a child with an infection in the same room with a child with leukemia.

Good handwashing is the most important way to control infection.

Observe the child closely and be alert for signs of impending infection.

Observe broken skin or mucous membrane for signs of infection.

Report fever of more than 101° F (38.3° C).

Assess central line site for redness or tenderness.

Administer growth factors, such as granulocyte colonystimulating factor, to stimulate the production of neutrophils and to decrease the incidence of severe infections in the child after high-dose chemotherapy.

Administer IV antibiotics, as ordered.

Administer PCP prophylaxis, such as co-trimoxazole, if ordered, twice daily three times per week to prevent infection with Pneumocystis carinii. (Dapsone and pentamidine are also given for patients unable to take co-trimoxazole.)

Record vital signs and report changes that may indicate hemorrhage, including:

Tachycardia.

Lowered blood pressure.

Pallor.

Diaphoresis.

Increasing anxiety and restlessness.

Observe for GI bleeding and Hematest all emesis and stool.

Move and turn the child gently because hemarthrosis may occur and may cause pain.

Handle the child in a gentle manner.

Turn the child frequently to prevent pressure ulcers.

Place the child in proper body alignment in a comfortable position.

Allow the child to be out of bed in a chair if this position is more comfortable.

Encourage the child to ambulate, if possible.

Avoid I.M. injections, if possible; if not possible, ensure platelet count has been obtained prior to injection and hold pressure to the area for at least 5 minutes.

Handle catheters and drainage and suction tubes carefully to prevent mucosal bleeding.

Protect the child from injury by monitoring activities and exposure to environmental hazards, such as slippery floors or uneven surfaces.

Be aware of emergency procedures for control of bleeding:

Apply local pressure carefully so as not to interfere with clot formation.

Administer leukocyte-poor, irradiated, packed RBCs and platelets, as ordered.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTPatients with low WBC count may not respond to infection with usual signs and symptoms (ie, fever and purulent drainage from infected wound).

Promoting Acceptance of Body Changes

Prepare patient for potential changes in body image (alopecia, weight loss, muscle wasting) and help child cope with related feelings.

Engage Child Life therapist for medical play and support.

Contact the school nurse and teacher to help them prepare for the child’s return to school. Discuss the bodily changes that have occurred and that may happen in the future.

Promoting Optimal Nutrition

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseBauer, J., Jurgens, H., & Fruhwald, M. C. (2011). Important aspects of nutrition in children with cancer. Advances in Nutrition, 2(2), 67-77.

Provide a highly nutritious diet as tolerated by the child.

Determine the child’s food likes and dislikes.

Offer frequent, small meals.

Offer high-calorie, high-protein supplemental feedings.

Encourage the parents to assist at mealtime.

Allow the child to eat with a group at a table if his or her condition allows.

Avoid foods high in salt while child is taking steroids.

Administer enteral and parenteral feeds, as ordered.

Give careful oral hygiene; the gums and mucous membranes of the mouth may bleed easily.

Use a soft toothbrush.

If the child’s mouth is bleeding or painful, clean the teeth and mouth with a moistened cotton swab or spongetipped swab.

Use a nonirritating rinse for the mouth (no alcohol-containing mouthwash or sodium bicarbonate).

Apply petroleum to dry, cracked lips.

Assess for mucositis and provide appropriate mouth rinse.

Be alert for nausea and vomiting.

Administer anti-emetic drugs on a round-the-clock, regular schedule (eg, serotonin antagonist, dexamethasone).

Become knowledgeable about chemotherapeutic agents and adjust anti-emetic therapy for those drugs with delayed nausea and vomiting.

Monitor strict intake and output.

Maintain parenteral fluid administration and assess for signs of dehydration or overhydration.

Administer anti-emetic drugs for patients who receive radiation to the chest, abdomen, pelvis, or craniospinal axis.

Suggest relaxation techniques or guided imagery for patients who experience anticipatory nausea and vomiting.

Relieving Pain

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseVan de Wetering, M. D., & Schouten-van Meeteren, N. Y. N. (2011). Supportive care for children with cancer. Seminars in Oncology, 38(3), 374-379.

Position the child for comfort.

Assess the child’s pain using a developmentally appropriate pain scale at regular intervals.

Administer drugs on a preventive schedule before pain becomes intense. Continuous infusion pumps for opioid administration are commonly used.

Manipulate the environment, as necessary, to increase the child’s comfort and to minimize unnecessary exertion.

Prepare the child for treatment and diagnostic procedures.

Use knowledge of growth and development to prepare the child for such procedures as bone marrow aspirations, spinal taps, blood transfusions, and chemotherapy.

Provide a means for talking about the experience. Play, storytelling, or role-playing may be helpful.

Convey to the child an acceptance of fears and anger.

Use anesthetic cream at spinal tap, injection, and bone marrow sites to decrease pain.

Administer conscious sedation before procedures and monitor pulse, BP, respirations, and pulse oximetry during and after procedures.

Consider implementing complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) interventions for pain control as well as for management of nausea, vomiting, and anxiety. CAM strategies to consider include:

Hypnosis/self-hypnosis.

Imagery.

Distraction/relaxation techniques.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Music therapy.

Massage.

Conserving Energy

Assess the child’s energy level and space needed activities accordingly. Allow the child to rest, if necessary.

Encourage the child to limit strenuous activity after such diagnostic procedures as bone marrow aspirations and spinal taps.

Reducing the Child’s Anxiety

Provide for continuity of care.

Encourage family-centered care.

Facilitate play activities for the child and use opportunities to communicate through play.

Maintain some discipline, placing calm limitations on unacceptable behavior.

Provide appropriate diversional activities.

Encourage independence and provide opportunities that allow the child to control his or her environment.

Explain the diagnosis and treatment in age-appropriate terms.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseCarter, B., Coad, J., Bray, L., et al. (2012). Home-based care for special healthcare needs: Community children’s nursing services. Nursing Research, 61(4), 260-268.

Begin to develop a home care plan before the child leaves the hospital.

Communicate with health care provider, hospital nurses, family, and others familiar with the case to gather information about the child’s illness, treatment plan, and specific needs in the home.

Arrange schedule for blood draws and how results will be managed.

Contact the child’s school and arrange a meeting with the school nurse, principal, and appropriate teachers to explain child’s diagnosis, treatment, and potential time away from school.

Discuss with patient the possibility of making a visit to the classroom; explain about cancer and the adverse effects of chemotherapy to facilitate school reentry.

Collaborate with primary care provider regarding immunization schedule and the contraindication for children on immunosuppressive therapy.

Make sure that parents or caregivers can demonstrate the proper technique for care of venous access, such as dressing changes, flushing, and assessing for infection.

Ensure parents or caregivers receive education for home medications, including medication schedule, side effects, and indications for scheduled and PRN medications.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Teach parents about normal CBC values and expected variations caused by therapy.

Instruct parents about leukemia and adverse effects of chemotherapy.

Tell parents to call the health care provider if child has a fever of more than 101° F (38.3° C), which may indicate overwhelming infection and impending septic shock, bleeding, and signs of infection. Parents should also immediately report if the child has been exposed to chickenpox. Immunosuppressed children are in danger of developing disseminated varicella and may be treated prophylactically with varicella immune globulin.

Teach preventive measures, such as handwashing and isolation from children with communicable diseases.

Reinforce that parents are never to use a rectal thermometer.

Refer parents to such agencies as Candlelighters (www.candlelighters.org) or the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (www.leukemia-lymphoma.org).

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Parents discuss their feelings about the child’s diagnosis and treatment.

Remains afebrile, no signs of localized infection or bleeding.

Maintains a positive body image.

Eats enough calories to maintain weight.

Experiences relief from pain (no crying or expression of pain).

Rests at intervals.

Acts out feelings in play; participates in age-appropriate activities.

Brain Tumors in Children

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseFlemming, A. J., & Chi, S. N. (2012). Brain tumors in children. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 42(2), 80-103.

Brain tumors are expanding lesions within the skull. Approximately 25% of the malignant tumors that occur in children are brain tumors, with an incidence rate of 4.84 per 100,000 children age 0 to 19. Four main types of brain tumors appear in children. Glial cell tumors, including astrocytoma and diffuse pontine glioma, can grow at any location in the brain and account for approximately 30% to 40% of all pediatric brain tumors. Medulloblastoma is a type of embryonal tumor, which is highly malignant and rapidly growing, usually found in the cerebellum. Embryonal tumors are the most common tumors of the CNS in children. Ependymoma is a tumor derived from the ependyma, or lining of the central canal of the spinal cord and cerebral ventricles. It frequently arises on the floor of the fourth ventricle, causing obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Ependymomas represent approximately 5% to 10% of all primary childhood CNS tumors. Germ cell tumors are midline tumors typically diagnosed in children age 6 to 14 with a higher incidence in parts of Asia, specifically Japan.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The etiology of brain tumors is unknown. Symptoms are associated with the location of the tumor and rate of growth.

Astrocytomas typically present in the infratentorial region, producing increased intracranial pressure (ICP). It is classified according to its malignancy, from grade I (least malignant) to grade IV (most malignant). Surgery and radiation are the primary therapies.

Medulloblastoma grows rapidly and produces evidence of increased ICP progressing during several weeks. It is classified as standard risk or high risk depending on tumor histology. Combination therapy of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy is usually required.

Germ cell tumors grow in the midline of the brain and the majority present in the supraseller or pineal regions. The growth rate varies, but frequently symptoms precede diagnosis by several months.

Ependymomas grow with varying speed. Because of location, tumors can invade the cardiorespiratory center, cerebellum, and spinal cord. They are graded according to degree of differentiation.

Clinical Manifestations

Glial Cell Tumors

Onset and growth is related to stage of tumor.

Medulloblastoma

Fast growing, malignant, and invasive.

The child may present with unsteady gait, anorexia, vomiting, and early morning headache.

May later develop ataxia, nystagmus, papilledema, drowsiness, increased head circumference, head tilt, and cranial nerve palsies. May develop obstructive hydrocephalus.

Germ Cell Tumor

Signs of midline shifts.

Visual disturbances.

Personality and sleep pattern alterations.

Dramatic weight loss.

Hydrocephalus.

Endocrinopathies.

Seizures.

Ependymoma of the Fourth Ventricle

Signs of increased ICP.

Nausea or vomiting.

Headache.

Unsteady gait or ataxia; dysmetria.

Focal motor weakness, vision disturbances, seizures.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Determined by the type of tumor that is suspected; usually includes many or all of the following procedures to localize and determine extent of the tumor:

Computed tomography (CT).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery imaging.

Positron emission tomography (PET).

Lumbar puncture with CSF cytologic evaluation.

Angiography (occasional).

Management

Surgery is performed to determine the type of tumor, to assess the extent of invasiveness, and to excise as much of the lesion as possible.

Radiation therapy is usually initiated as soon as the diagnosis is established and the surgical wound is healed.

Chemotherapy is used to treat chemoresponsive tumors and is particularly important in children who are too young to receive radiation therapy.

A ventriculoperitoneal shunt is usually necessary for children who develop hydrocephalus.

The use of immunotherapy is being investigated for potential for future treatment.

Prognosis is improved in cases that involve early diagnosis and adequate therapy. Five-year survivors are increasing, especially in children with low-grade astrocytomas or ependymomas. However, there are still tumors such as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma that have no known cure.

Complications

Brain stem herniation.

Hydrocephalus.

Nursing Assessment

Assess the child’s neurologic status to help locate the site of the tumor and the extent of involvement as well as to identify signs of disease progression.

Obtain a thorough nursing history from the child and parents, particularly data related to normal behavioral patterns and presenting symptoms.

Perform portions of the neurologic examination, as appropriate. Assess muscle strength, coordination, gait, and posture.

Observe for the appearance or disappearance of the clinical manifestations previously described. Report these to the health care provider and record each of the following in detail:

Headache—duration, location, severity.

Vomiting—time of occurrence, projectile, blood.

Seizures—activity before seizure, type of seizure, areas of body involved, behavior during and after seizure.

Monitor vital signs frequently, including BP and pupillary reaction.

Monitor ocular signs. Check pupils for size, equality, reaction to light, and accommodation.

Observe for signs of brain stem herniation—should be considered a neurosurgical emergency.

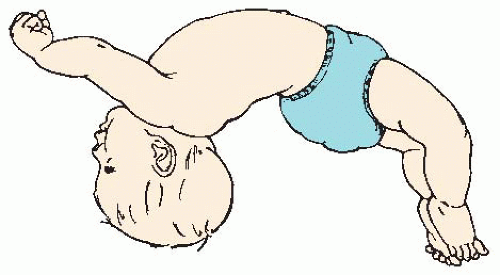

Attacks of opisthotonos (see Figure 51-2).

Tilting of the head; neck stiffness.

Poorly reactive pupils.

Increased BP; widened pulse pressure.

Change in respiratory rate and nature of respirations

Irregularity of pulse or lowered pulse rate.

Alterations of body temperature.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access