Pediatric Neurologic Disorders

NEUROLOGIC AND NEUROSURGICAL DISORDERS

It is essential to have strong knowledge of growth and development and use physical assessment skills while caring for a child with a neurological or neurosurgical condition. Young children often cannot either speak or express how they feel, so a good ongoing physical assessment is essential. Parents and caregivers are also a valuable information source as to differences in their child’s physical condition and should always be included in the assessment. It is also important to remember that children are not little adults. They have their own unique physiology, which is important to consider when assessing and understanding the manifestation of neurological conditions in children. The plasticity of the infant brain can make for greater recovery than that of an adolescent.

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a nonprogressive disorder of posture and movement. It is a result of a fixed lesion or anomaly of the brain that occurred in the early stages of brain development. The incidence of CP is 2 to 2.5 per 1,000 live births. The rate of CP in premature infants continues to rise as survival rates have increased in such infants.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Antenatal Causes (80% of all cases)

Vascular occlusion.

Cortical migration disorders.

Structural maldevelopment during gestation—gene deletions.

Genetic syndromes.

Congenital infection.

Natal Causes (10% of all cases)

Hypoxic ischemic injury at birth.

Postnatal Causes (10% of all cases)

Preterm infants vulnerable to brain damage from periventricular leukomalacia secondary to ischemia and/or severe intraventricular hemorrhage.

Meningitis, encephalitis, encephalopathy, head trauma (accidental and nonaccidental).

Symptomatic hypoglycemia, hydrocephalus, hyperbilirubinemia.

Types of Cerebral Palsy

CP can be classified into three categories.

Neuropathic—motor dysfunction.

Spastic: hyperreflexia, hypertonicity, clonus, Babinski sign.

Athetoid: involuntary movements, dystonia, no joint contractures.

Ataxic: lack of balance and coordination, wide-based gait.

Mixed: spastic and athetoid signs, total body usually involved.

Hypotonic: rare in the first 2 to 3 years, evolves into athetoid.

Anatomic—region of involvement.

Monoplegia: one limb involved, usually spastic.

Hemiplegia: spastic ipsilateral limbs.

Paraplegia: lower limbs only, familial type.

Diplegia: lower limbs more involved than upper limbs, spastic.

Triplegia: three limbs involved.

Quadriplegia—all four limbs involved including head, neck, and trunk.

Functional.

Independent community ambulators.

Dependent community ambulators.

Wheelchair bound.

Clinical Manifestations

The types of CP mentioned above correlate with clinical presentation.

Early clinical signs include:

Abnormal tone and limb and/or trunk posture in infancy with delay in achieving motor milestones, with or without slowing of head growth.

Difficulty or slow feeding, gagging and vomiting, oromotor incoordination.

Abnormal gait once child is walking.

Asymmetric hand function before age 12 months.

Persistence of primitive reflexes.

Common associated findings include:

Seizures.

Hearing impairment.

Visual impairment.

Mental retardation.

Speech and language disorders.

Growth disorders, developmental delays.

Gastroesophageal reflux, nutritional deficiencies (due to poor feeding, reflux, aspiration).

Behavioral/emotional problems.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnosis is based on clinical examination and history. Various testing also helps determine cause or evaluate for associated problems.

Neuroimaging—magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT).

Recommended when cause has not been identified.

MRI is preferred over CT as it has a higher yield for suggesting the cause and timing of the insult.

Metabolic and genetic testing.

Not routinely required.

Should be considered in cases when the clinical history or findings on neuroimaging do not identify a specific structural abnormality or if additional and atypical features in the history or clinical examination are identified.

Consider completing testing for coagulation disorders, particularly in children with a hemiplegic CP as the incidence of cerebral infarction is very high in these children.

Associated conditions.

Electroencephalography (EEG) should not be obtained for the purpose of determining cause, but should be obtained when there is evidence on history and examination suggesting epilepsy or epileptic syndrome.

Initial assessment should include screening for mental retardation, ophthalmologic and hearing impairments, speech and language disorders, and oral-motor dysfunction, as many children with CP have these associated deficits.

Management

Spasticity should be treated first to improve function, reduce pain, and provide ease in caregiving. It requires an organized approach and begins with thorough assessment.

Focal spasticity.

Botulinum injections help reduce spasticity and improve gait; may be given in upper or lower limbs. Botulinum toxin type A is an effective and generally safe treatment.

Serial casting may be done with or without Botulinum injections.

Generalized spasticity.

Diazepam is usually used for short-term treatment of generalized spasticity; tizanidine may also be used.

Currently there is insufficient evidence to support the use of dantrolene, oral baclofen, or continuous intrathecal baclofen.

Evidence Base

Evidence Base

Delgado, M. R., Hirtz, D., Aisen, M., et al. (2010). Practice parameter: Pharmacologic treatment of spasticity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (an evidence-based review). Neurology, 74, 336-343.

DRUG ALERT Intrathecal baclofen lowers the seizure threshold. Children may develop severe withdrawal syndrome characterized by fever, hypertension, tachycardia, agitation, and hallucinations. May occur in situations of pump malfunction, catheter breakage, or improper filling of pump.

DRUG ALERT Intrathecal baclofen lowers the seizure threshold. Children may develop severe withdrawal syndrome characterized by fever, hypertension, tachycardia, agitation, and hallucinations. May occur in situations of pump malfunction, catheter breakage, or improper filling of pump.

Selective dorsal rhizotomy—25% to 60% of dorsal nerve rootlets are cut from L4 to S1 through a L1-S1 laminectomy (guided by the response to intraoperative electromyogram).

Monitor for and treat scoliosis and hip subluxation.

Scoliosis is very common and increases with age and severity of CP; highest risk is among the nonambulatory.

Curve progression occurs most quickly during a growth spurt but, unlike idiopathic scoliosis, may continue to progress after skeletal maturity.

Early detection is critical to slow progression. Interventions, such as external bracing, customized seating and seating inserts, and maintenance of good seating posture by correcting hip and pelvic deformities, is essential in preventing or delaying the need for corrective spine surgery.

Hip subluxation and dislocation results from spasticity in hip adductors and iliopsoas muscles; if left untreated, it may result in acetabular dysplasia and degenerative joint disease.

Growth and nutritional problems are common among children with moderate to severe CP, resulting in poor health, increase in use of health resources, and decreased participation in school and community activities; may require gastrostomy tube feeding.

Drooling results from impaired swallowing or poor lip closure.

Anticholinergic medications, such as glycopyrolate and hydroxyzine, are used but have significant side effects.

It has recently been reported that injecting Botulinum toxin into the parotid glands decreased salivary flow without the side effects seen with anticholinergic therapy.

Surgery to treat sialorrhea (excessive saliva secretion) may be of benefit.

Treatment of involuntary movements.

Dystonia—levodopa is used as an initial medication; trihexyphenidyl may also be used.

Chorea—benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam, and dopamine-depleting medications, such as haloperidol, are used.

Treatment of hemisyndromes.

Balance training improves symmetry of gait.

Constraint-induced movement therapy—affected arm/hand is restrained for a prolonged period of time, which results in increased use of the affected hand; well tolerated in children.

Treatment of osteopenia.

Encourage weight-bearing activities (use of stander, rolator walker).

Provide vitamin D and calcium supplements.

Bisphosphonates may be considered for those children with low bone mineral density and those who are at particular risk for fragility fractures.

Risk for fracture is assessed through bone density scanning and other tests and is reported as the Z score. It is not valid in children less than 5 years old.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseFehlings, D., Switzer, L., Agarwal, P., et al. (2012). Informing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for children with cerebral palsy at risk of osteoporosis: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 54, 106-116.

Complications

Contractures.

Hip subluxation/dislocation.

Malnutrition.

Scoliosis.

Osteopenia/fractures.

Gastroesophageal reflux.

Constipation.

Seizures.

Spasticity.

Pain.

Nursing Assessment

Perform a functional assessment; determine ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs).

Perform a developmental assessment; use Denver II developmental or other screening tools.

Evaluate ability to protect airway—gag reflex, swallowing.

Assess nutritional status—growth, signs of deficiency, risk of aspiration.

Assess neuromuscular function and mobility—range of motion (ROM), spasticity, coordination.

Assess speech, hearing, vision.

Evaluate parent-child interaction.

Determine parents’ understanding of and compliance with treatment plan.

Assess skin for pressure sores, especially in areas of friction (splints).

Assess for presence of pain (chronic or acute due to hip subluxation, dislocation).

Nursing Diagnoses

Impaired Physical Mobility related to altered neuromuscular functioning.

Delayed Growth and Development related to the nature and extent of the disorder.

Interrupted Family Processes related to nature of disorder, role disturbances, and uncertain future.

Risk for Injury related to deficit in motor activity and coordination.

Nursing Interventions

Increasing Mobility and Minimizing Deformity

Teach the parents to carry out appropriate exercises under the direction of the physical therapist and occupational therapist.

Use splints and braces to facilitate muscle control and improve body functioning.

Apply, as directed.

Remove for recommended time.

Inspect underlying skin for redness, irritation, skin breakdown, and signs of improper application or fit of splints or orthoses.

Regularly inspect orthoses for cracks, loose screws, or broken Velcro straps.

Use splint as directed for constraint-induced therapy in children with unilateral CP.

Use assistive devices, such as adapted grooming tools, writing implements, and utensils, to enhance independence. Handles of toothbrushes, spoons, and forks can be built up with sponges or specially curved to make holding easier.

Encourage self-dressing with easy pull-on pants, large sweatshirts, Velcro closures, and other loose clothing.

Use play, such as board games, ball games, pegboards, and puzzles, to improve coordination.

Maintain good body alignment to prevent contractures.

Provide adequate rest periods.

Avoid exciting events before rest or bedtime.

Administer or teach parents about side effects of medications and how to administer medications, as prescribed.

Maximizing Growth and Development

Evaluate the child’s developmental level and then assist with age-appropriate tasks.

Provide for continuity of care at home, daycare, therapy centers, and the hospital.

Obtain a thorough history from the parents regarding the child’s usual home routines, weaknesses and strengths, and likes and dislikes.

Communicate with representatives from all disciplines involved in the child’s care to ensure that the specific needs of the child are identified.

Formulate a consistent care plan that incorporates the goals of all related disciplines and meets the needs of the child and family. Include in the care plan guidelines for the following:

Feeding.

Sleeping.

Physical therapy.

Play.

Other ways to foster growth and development.

Medications.

Psychosocial needs.

Family needs.

Pain assessment/management.

During feeding, maintain a pleasant, distraction-free environment.

Provide a comfortable chair.

Serve the child alone, initially. After the child begins to master the task of eating, encourage the child to eat with other children.

Do not attempt feedings if the child is very fatigued.

Find the eating position in which the child can be most self-sufficient.

Allow the child to hold the spoon even if self-feeding is minimal.

Stand behind and reach over the child’s shoulder to guide the spoon from the plate to the child’s mouth.

Serve foods that stick to the spoon, such as thick applesauce or mashed potatoes.

Encourage finger foods that the child can handle alone.

Provide appropriate assistive devices for independent feeding, such as spoon and fork with special handles, plate and glass holders, and special feeding chair.

Disregard “messy” eating; use a large plastic bib, smock, or towel to protect the child’s clothes.

If the child must be fed, do so slowly and carefully. Be aware of difficulty sucking and swallowing caused by poor muscle control. Cut large pieces of food into small pieces.

Be alert for associated sensory deficits that delay development and could be corrected.

Hearing, speech, vision.

Squinting, failure to follow objects, or bringing objects very close to the face.

Strengthening Family Processes

Assess parental coping and provide anticipatory guidance, emotional support, and contact with social worker, as needed.

Help the parents to recognize immediate needs and identify short-term goals that can be integrated into the long-term plan.

Assess for caregiver burden due to the numerous challenges of daily care and link with appropriate resources (eg, home care, respite, funding) and provide access to social work for assistance in obtaining such support.

Provide positive feedback for effective parenting skills and positive approaches to caring for the child.

Assist the parents to deal with siblings’ responses to the disabled child.

Encourage parents to find time to spend with each sibling separately.

Encourage family to maintain contact with friends and community and engage in outside activities as much as possible.

Suggest family counseling.

Assist parents to find local resources to help in the child’s care.

Contact hospital social worker or discharge planner for information about local CP organizations, chapters, funding sources, community supports, or charities.

Use the Internet to identify national and regional programs that may have local chapters.

Protecting the Child from Injury

Evaluate the child’s need for specific safety measures, such as suction machine, safety helmet, or seizure precautions, and modify the environment as appropriate to ensure the child’s safety.

Provide for frequent position changes and adequate fit on orthotics, wheelchairs, and walking or standing devices to prevent skin breakdown. Assess skin integrity daily.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Assess the home environment for safety. Stairs should be gated and paths should be cleared for walking with assistive devices or for adequate passage of wheelchairs, walkers, etc.

Assist parents in arranging for equipment that may be required in the home (eg, wheelchair, pump for intermittent G-tube feedings, walkers).

Check all adaptive equipment, braces, and walkers for correct fit. Arrange for replacement, as needed.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Instruct the parents in all areas of the child’s physical care.

Encourage regular medical and dental evaluations.

Advise parents that the child needs discipline to feel secure.

Refer parents to such agencies as the United Cerebral Palsy Association of America (www.ucp.org).

Connect families with other families who have a child with CP so that they may provide a supportive network.

Encourage maintenance of good nutritional status.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Dresses and feeds self as independently as possible; minimal contractures noted.

Consistent growth curve maintained; sequential developmental milestones consistent with condition achieved.

Family participates in usual school and community activities; uses respite care when available.

Safety equipment used; no injury reported.

Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is characterized by an increased volume of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is associated with progressive ventricular dilatation. There are two main categories of hydrocephalus: communicating and noncommunicating. Hydrocephalus occurs with such conditions as tumors, infections, congenital malformations, and hemorrhage. The incidence of hydrocephalus is 0.5 to 4 per 1,000 live births.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Noncommunicating hydrocephalus—obstruction of CSF flow within the ventricular system or blockage of CSF flow from the ventricular system to the subarachnoid space.

May be partial, intermittent, or complete.

More common than communicating type.

Congenital causes.

Aqueductal stenosis.

Congenital lesions (vein of Galen malformation, congenital tumors).

Arachnoid cyst.

Chiari malformations (with or without myelomeningocele).

X-linked hydrocephalus.

Dandy-Walker malformation.

Acquired causes.

Aqueductal gliosis (posthemorrhagic or postinfectious).

Space-occupying lesions (tumors or cysts).

Head injuries.

Communicating hydrocephalus—CSF circulates through the ventricular system into the subarachnoid space with no obstruction.

Congenital causes.

Achondroplasia.

Arachnoid cyst.

Craniofacial syndromes.

Acquired causes.

Posthemorrhagic (intraventricular or subarachnoid)

Choroid plexus papilloma or choroid plexus carcinoma

Venous obstruction (eg, superior vena cava syndrome)

Postinfectious

BOX 46-1 Signs and Symptoms of Increased Intracranial Pressure in Infants and Children

Vomiting

Restlessness and irritability

High-pitched, shrill cry (infants)

Rapid increase in head circumference (infants)

Tense, bulging fontanelle (infants)

Changes in vital signs:

Increased systolic blood pressure

Decreased pulse

Decreased and irregular respirations

Increased temperature

Pupillary changes

Papilledema

Possible seizures

Lethargy, stupor, coma

Older children may also experience:

Headache, especially on awakening

Lethargy, fatigue, apathy

Personality changes

Separation of cranial sutures (may be seen in children up to age 10)

Visual changes such as double vision

Clinical Manifestations

May be rapid, slow and steadily advancing, or intermittent. Clinical signs depend on the age of the child, whether the anterior fontanelle has closed, whether the cranial sutures have fused, and the type and duration of hydrocephalus.

Infants

Excessive head growth (may be seen up to age 3).

Delayed closure of the anterior fontanelle.

Fontanelle tense and elevated above the surface of the skull.

Signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (see Box 46-1).

Alteration of muscle tone of the extremities, including clonus or spasticity.

Later physical signs:

Forehead becomes prominent (“bossing”).

Scalp appears shiny with prominent scalp veins.

Eyebrows and eyelids may be drawn upward, exposing the sclera above the iris.

Infant cannot gaze upward, causing “sunset eyes.”

Strabismus, nystagmus, and optic atrophy may occur.

Infant has difficulty holding head up.

Child may experience physical or mental developmental lag.

Pseudobulbar palsy (difficulty sucking, feeding, and phonation, which leads to regurgitation, drooling, and aspiration).

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTIt is important to measure head circumference because the infant’s skull is highly elastic and can accommodate an increase in ventricular size. Ventriculomegaly may progress without obvious signs of increased ICP.

Older Children

Older children have closed sutures and present with signs of increased ICP.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Percussion of the infant’s skull may produce a typical “cracked pot” sound (MacEwen’s sign).

Ophthalmoscopy may reveal papilledema.

MRI is the diagnostic tool of choice.

CT is also used for diagnosis in cases where sedation poses added risk due to need for general anesthetic or in situations in which MRI is not available.

Ultrasonography is also used.

Management

Hydrocephalus can be treated through a variety of surgical procedures, including direct operation on the lesion causing the obstruction, such as a tumor; intracranial shunts for selected cases of noncommunicating hydrocephalus to divert fluid from the obstructed segment of the ventricular system to the subarachnoid space; and extracranial shunts (most common) to divert fluid from the ventricular system to an extracranial compartment, frequently the peritoneum or right atrium. CSF production may also be reduced by medication or surgical intervention.

Extracranial Shunt Procedures

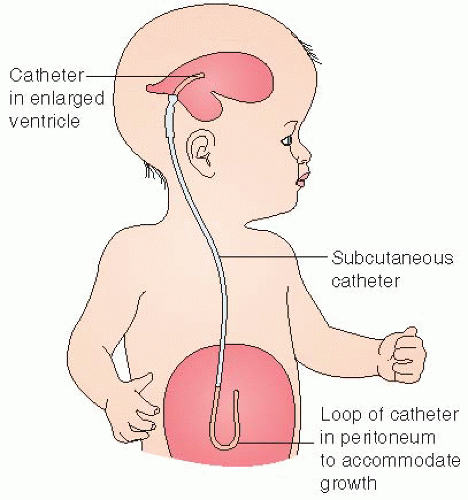

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt (see Figure 46-1):

Diverts CSF from a lateral ventricle or the spinal subarachnoid space to the peritoneal cavity.

A tube is passed from the lateral ventricle through an occipital burr hole subcutaneously through the posterior aspect of neck and paraspinal region to the peritoneal cavity through a small incision in the right lower quadrant.

A ventricular access device is an implanted reservoir and catheter used for premature neonates less than 2,000 g in lieu of a shunt. The catheter drains fluid from the ventricles into the reservoir, which can then be emptied using aseptic technique. When infant weight exceeds 2,000 g, a shunt can be placed.

Ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt:

A tube is passed from the dilated lateral ventricle through a burr hole in the parietal region of the skull.

It then is passed under the skin behind the ear and into a vein down to a point where it discharges into the right atrium or superior vena cava.

A one-way pressure-sensitive valve will close to prevent reflux of blood into the ventricle and open as ventricular pressure rises, allowing fluid to pass from the ventricle into the bloodstream.

Ventriculopleural shunt:

Diverts CSF to the pleural cavity.

Indicated when the VP or VA route cannot be used.

Ventricle-gall bladder shunt:

Diverts CSF to the common bile duct.

Used when all other routes are unavailable.

Most shunts have the following components:

Ventricular tubing.

A one-way or unidirectional pressure-sensitive flow valve.

A pumping chamber.

Distal tubing.

Programmable shunts are available. These can be programmed to a certain flow pressure and pressure settings can be readjusted based on patient response. A magnetic device is used to adjust the pressure setting of the shunt valve. The use of a programmable shunt eliminates the need for multiple surgeries or hospital visits to adjust shunt pressure.

Shunt Complications

Need for shunt revision frequently occurs because of occlusion, infection, or malfunction, especially in the first year of life.

Shunt revision may be necessary because of growth of the child. Newer models, however, include coiled tubing to allow the shunt to grow with the child.

Shunt dependency frequently occurs. The child rapidly manifests symptoms of increased ICP if the shunt does not function optimally. Onset may be sudden or insidious.

Children with VA shunts may experience endocardial contusions and clotting, leading to bacterial endocarditis, bacteremia, and ventriculitis or thromboembolism and cor pulmonale.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on early diagnosis and prompt therapy and the underlying etiology.

With improved diagnostic and management techniques, the prognosis is becoming considerably better.

Many children experience normal motor and intellectual development.

The severity of neurologic deficits is directly proportional to the interval between onset of hydrocephalus and the time of diagnosis.

Approximately two thirds of patients will die at an early age if they do not receive surgical treatment.

Surgery reduces mortality and decreases morbidity, with a survival rate of greater than 90%.

Complications

Seizures, headaches.

Herniation of the brain.

Spontaneous arrest due to natural compensatory mechanisms, persistent increased ICP, and brain herniation.

Developmental delays.

Depression in adolescents is common.

Shunt malfunctions.

Nursing Assessment

Infants

Assess head circumference.

Measure at the occipitofrontal circumference—point of largest measurement.

Measure the head at approximately the same time each day.

Use a centimeter measure for greatest accuracy.

Palpate fontanelle for firmness and bulging.

Assess pupillary response.

Assess level of consciousness (LOC).

Evaluate breathing patterns and effectiveness.

Assess feeding patterns and patterns of emesis.

Assess motor function.

Assess developmental milestones.

Older Children

Measure vital signs for signs of increased ICP.

Assess patterns of headache, emesis.

Determine pupillary response.

Evaluate LOC using the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Assess motor function.

Evaluate attainment of milestones, school performance.

Assess for behavioral changes.

Nursing Diagnoses

Ineffective Cerebral Tissue Perfusion related to increased ICP before surgery.

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to reduced oral intake and vomiting.

Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to alterations in LOC and enlarged head.

Anxiety of parents related to child undergoing surgery.

Risk for Injury related to malfunctioning shunt.

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to CSF drainage, decreased intake postoperatively.

Risk for Infection related to bacterial infiltration of the shunt.

Ineffective Family Coping related to diagnosis and surgery.

Nursing Interventions

Maintaining Cerebral Perfusion

Observe for evidence of increased ICP and report immediately.

NURSING ALERT Brain stem herniation can occur with increased ICP and is manifested by opisthotonic positioning (flexion of head and feet backward). This is a grave sign and may be followed by respiratory arrest. Prepare for emergency resuscitation and corrective measures, as directed.

NURSING ALERT Brain stem herniation can occur with increased ICP and is manifested by opisthotonic positioning (flexion of head and feet backward). This is a grave sign and may be followed by respiratory arrest. Prepare for emergency resuscitation and corrective measures, as directed.

Assist with diagnostic procedures to determine cause of hydrocephalus and indication for surgical intervention.

Explain the procedure to the child and parents at their levels of comprehension.

Administer prescribed sedatives 30 minutes before the procedure to ensure their effectiveness.

Organize activities so that the child is permitted to rest after administration of the sedative.

DRUG ALERT Sedatives are contraindicated in many cases because increased ICP predisposes the child to hypoventilation or respiratory arrest. If they are administered, the child should be observed very closely for evidence of respiratory depression.

DRUG ALERT Sedatives are contraindicated in many cases because increased ICP predisposes the child to hypoventilation or respiratory arrest. If they are administered, the child should be observed very closely for evidence of respiratory depression.

Observe closely after ventriculography for the following:

Leaking CSF from the sites of subdural or ventricular taps. These tap holes should be covered with a small piece of gauze or other dressing per institutional policy.

Reactions to the sedative, especially respiratory depression.

Changes in vital signs indicative of shock.

Signs of increased ICP, which may occur if air has been injected into the ventricles.

Providing Adequate Nutrition

Be aware that feeding is frequently difficult because the child may be listless, have a diminished appetite, and be prone to vomiting.

Complete nursing care and treatments before feeding so that the child will not be disturbed after feeding.

Hold the infant in a semi-sitting position with head well supported during feeding. Allow ample time for bubbling.

Offer small, frequent feedings.

Place the child on side with head elevated after feeding to prevent aspiration.

Maintaining Skin Integrity

Prevent pressure sores (pressure sores of the head are a frequent problem) by placing the child on a sponge rubber or lamb’s wool pad or an alternating-pressure or egg-crate mattress to keep weight evenly distributed. Be mindful of latex allergies and the type of padding used.

Keep the scalp clean and dry.

Turn the child’s head frequently; change position at least every 2 hours.

When turning the child, rotate head and body together to prevent strain on the neck.

A firm pillow may be placed under the child’s head and shoulders for further support when lifting the child.

Keep weight off incision during immediate postoperative period.

Provide meticulous skin care to all parts of the body and observe skin for signs of breakdown or pressure.

Give passive ROM exercises to the extremities, especially the legs.

Keep the eyes moistened with artificial tears if the child is unable to close the eyelids normally. This prevents corneal ulcerations and infections.

Reducing Anxiety

Prepare the parents for their child’s surgery by answering questions, describing what nursing care will take place postoperatively, and explaining how the shunt will work.

Encourage the parents to discuss all the risks and benefits with the surgeon. Help them to understand the prognosis and what to expect of the child’s neurologic and cognitive development.

Prepare the child for surgery by using dolls or other forms of play to describe what interventions will occur.

Improving Cerebral Tissue Perfusion Postoperatively

Monitor the child’s temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure (BP), and pupillary size and reaction every 15 minutes until stable; then monitor every 1 to 2 hours or as indicated by child’s condition and institutional policy.

Maintain normothermia.

Provide appropriate blankets or covers, an Isolette or infant warmer, or hypothermia blanket.

Administer a tepid sponge bath or antipyretic medication for temperature elevation.

Aspirate mucus from the nose and throat, as necessary, to prevent respiratory difficulty.

Turn the child frequently.

Promote optimal drainage of CSF through the shunt by pumping the shunt and positioning the child, as directed.

If pumping is prescribed, carefully compress the valve the specified number of times at regularly scheduled intervals.

Report any difficulties in pumping the shunt.

Gradually elevate the head of child’s bed to 30 to 45 degrees, as ordered. Initially, the child will be positioned flat to prevent excessive CSF drainage.

Assess for excessive drainage of CSF.

Sunken fontanelle, agitation, restlessness (infant).

Decreased LOC (older child).

Assess closely for increased ICP, indicating shunt malfunction.

Note especially change in LOC, change in vital signs (increased systolic BP, decreased pulse rate, decreased or irregular respirations), vomiting, pupillary changes.

Report these changes immediately to prevent cerebral hypoxia and possible brain herniation.

Prevent excessive pressure on skin overlying shunt by placing cotton behind and over the ears under the head dressing and avoiding positioning the child on the area of the valve or the incision until the wound is healed.

Maintaining Fluid Balance

Accurately measure and record total fluid intake and output.

Administer intravenous (IV) fluids, as prescribed; carefully monitor infusion rate to prevent fluid overload.

Use a nasogastric tube, if necessary, for abdominal distention. This is most frequently used when a VP shunt has been performed.

Measure the drainage and record the amount and color.

Monitor for return of bowel sounds after nasogastric suction has been disconnected for at least 30 minutes.

Give frequent mouth care while the child is to have nothing by mouth.

Begin oral feedings when the child is fully recovered from the anesthetic and displays interest.

Begin with small amounts of dextrose 5% in water.

Gradually introduce formula.

Introduce solid foods suitable to the child’s age and tolerance.

Encourage a high-protein diet.

Observe for and report any decrease in urine output, increased urine-specific gravity, diminished skin turgor, dryness of mucous membranes, or lethargy, indicating dehydration.

Preventing Infection

Assess for fever (temperature normally fluctuates during the first 24 hours after surgery), purulent drainage from the incision, or swelling, redness, and tenderness along the shunt tract.

Administer prescribed prophylactic antibiotics.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTAll children who have had surgery require pain assessments. Although pain management is institution specific, acetaminophen is often the medication of choice. Also use alternative modes of pain management, such as distraction and relaxation techniques and ensure a quiet environment.

Strengthening Family Coping

Begin discharge planning early, including specific techniques for care of the shunt and suggested methods for providing daily care.

Turning, holding, and positioning.

Skin care over shunt.

Exercises to strengthen muscles—incorporated with play.

Feeding techniques and schedule.

Pumping the shunt.

Accompany all instructions with reassurance necessary to prevent the parents from becoming anxious or fearful about assuming the care of the child.

Help the parents to assist siblings to understand hydrocephalus and the child’s special needs. Encourage parents to spend individual time with siblings and not to neglect their needs as well. Suggest family counseling, if needed.

Assist parents in locating additional resources.

Social worker, discharge planner, or department of social services.

Visiting or home health nurses or aides.

Parent groups.

Community agencies.

Special programs at school.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Follow the community and home care considerations listed under “Cerebral Palsy” on page 1548. Check shunt functioning regularly and reinforce parental performance of shunt checks and assessment for shunt malfunction and increased ICP.

Perform total physical assessment regularly, looking for signs of trauma or skin breakdown.

Patient should wear a medical alert bracelet when he or she starts to attend school or daycare.

Make sure that parents or caregivers are certified in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Stress the importance of recognizing symptoms of increased ICP and reporting them immediately.

Advise parents to report shunt malfunction or infection immediately to prevent increased ICP.

Teach parents that illnesses that cause vomiting and diarrhea or illnesses that prevent an adequate fluid intake are a great threat to the child who has had a shunt procedure. Advise parents to consult with the child’s health care provider about immediate treatment of fever, control of vomiting and diarrhea, and replacement of fluids.

Tell the parents that few restrictions are required for children with shunts and to consult with the health care provider about specific concerns.

Alert parents that additional information and support are available from the Hydrocephalus Association (www.hydroassoc.org).

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

No changes in vital signs, LOC, or head size; no vomiting; pupils equal and responsive.

Feeds every 4 hours without vomiting; no significant weight loss.

No erythema, blanching, or skin breakdown; wound healing evident.

Parents verbalizing purpose and type of operative procedure, risks, and benefits.

Shunt pumping without resistance; stable LOC and vital signs.

Urine output equal to intake; skin turgor normal; electrolytes within normal limits.

Afebrile; no drainage from shunt site.

Parents actively seeking resources.

Spina Bifida

Spina bifida, also called spinal dysraphia, is a malformation of the spine in which the posterior portion of the laminae of the vertebrae fails to close. It occurs in approximately 1 per 1,000 live births in the United States and is the most common developmental defect of the central nervous system (CNS). It is more common in Caucasians than in other races. The incidence of spina bifida defects has been declining in the United States and United Kingdom due to antenatal screening and changes in environmental factors such as the consumption of folic acid in early pregnancy.

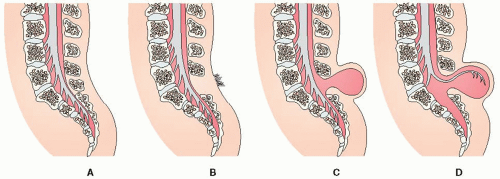

Several types of spina bifida are recognized, of which the following three are most common (see Figure 46-2).

Figure 46-2. Spina bifida. (A) Normal spine. (B) Spina bifida occulta. (C) Spina bifida with meningocele. (D) Spina bifida with myelomeningocele. |

Spina Bifida Occulta

Spina bifida occulta is seen in 10% of the United States population. It is a result of the posterior verteberal arches failing to fuse. A fat pad, dermal sinus, hairy tuft, or dimple in the lower back/lumbosacral region is often seen.

Meningocele

Meningocele is a herniation of the meninges through the defective posterior arches. The sac does not contain neural elements.

Myelomeningocele (or Meningomyelocele)

The spinal nerve roots and cord membranes protrude through the defect in the laminae of the vertebral column. Myelomeningoceles are covered by a thin membrane.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Unknown etiology, but generally thought to result from genetic predisposition triggered by something in the environment.

Certain drugs, including valproic acid, have been known to cause neural tube defects if administered during pregnancy.

Women who have spina bifida and parents who have one affected child have an increased risk of producing children with neural tube defects.

Involves an arrest in the orderly formation of the vertebral arches and spinal cord that occurs between the 4th and 6th weeks of embryogenesis.

Theories of causation include:

Incomplete closure of the neural tube during the 4th week of embryonic life.

The neural tube forms adequately, then ruptures.

DRUG ALERT Maternal periconceptional use of folic acid supplementation reduces by 50% or more the incidence of neural tube defects in pregnancies at risk.

DRUG ALERT Maternal periconceptional use of folic acid supplementation reduces by 50% or more the incidence of neural tube defects in pregnancies at risk.

In spina bifida occulta, the bony defect may range from a very thin slit separating one lamina from the spinous process to a complete absence of the spine and laminae.

A thin, fibrous membrane sometimes covers the defect.

The spinal cord and its meninges may be connected with a fistulous tract extending to and opening onto the surface of the skin.

In meningocele, the defect may occur anywhere on the cord. Higher defects (from thorax and upward) are usually meningoceles.

Surgical correction is necessary to prevent rupture of the sac and subsequent infection.

Prognosis is good with surgical correction.

In myelomeningocele (meningomyelocele), the lesion contains both the spinal cord and cord membranes.

A bluish area may be evident on the top because of exposed neural tissue.

The sac may leak in utero or may rupture after birth, allowing free drainage of CSF. This renders the child highly susceptible to meningitis.

Of all defects known as spina bifida cystica, 95% are myelomeningoceles and 5% are meningoceles.

Clinical Manifestations

Spina Bifida Occulta

Most patients have no symptoms.

They may have a dimple in the skin or a growth of hair over the malformed vertebra.

There is no externally visible sac.

With growth, the child may develop foot weakness or bowel and bladder sphincter disturbances.

This condition is occasionally associated with more significant developmental abnormalities of the spinal cord, including syringomyelia and tethered cord.

Meningocele

An external cystic defect can be seen in the spinal cord, usually in the midline.

The sac is composed only of meninges and is filled with CSF.

The cord and nerve roots are usually normal.

There is seldom evidence of weakness of the legs or lack of sphincter control.

Myelomeningocele

A round, raised, and poorly epithelialized area may be noted at any level of the spinal column. However, the highest incidence of the lesion occurs in the lumbosacral area.

Hydrocephalus occurs in approximately 90% of children with myelomeningocele due to associated Arnold-Chiari malformation, which causes a block in the flow of CSF through the ventricles.

Loss of motor control and sensation below the level of the lesion can occur. These conditions are highly variable and depend on the size of the lesion and its position on the cord.

A low thoracic lesion may cause total flaccid paralysis below the waist.

A small sacral lesion may cause only patchy spots of decreased sensation in the feet.

Contractures may occur in the ankles, knees, or hips. Hips may become dislocated.

Nature and degree of involvement depend on size and location of lesion.

This occurs because some fibers of innervation get through. One side of a hip, knee, or ankle may be innervated while the opposing side may not be. The unopposed side then becomes pulled out of position.

Clubfeet are a common accompanying anomaly; thought to be related to the position of paraplegic feet in the uterus.

Bladder dysfunction occurs because of how the sacral nerves that innervate the bladder are affected. The bladder fails to respond to normal messages that it is time to void and simply fills and overflows, causing incontinence and susceptibility to urinary tract infections (UTIs) because of incomplete emptying.

Fecal incontinence and constipation are caused by poor innervation of the anal sphincter and bowel musculature.

Most children have average intellectual ability despite hydrocephalus. Developmental disabilities include the following:

Gross motor development—children will need assistance in gaining and maintaining mobility.

Most children are able to learn in a “mainstream” school environment, provided they are able to overcome other barriers (architectural and attitudinal).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Prenatal detection is done through prenatal ultrasound and fetal MRI. This testing should be offered to all women at risk (women who are affected or who have had other affected children).

Diagnosis is primarily based on clinical manifestations.

CT scan and MRI may be performed to further evaluate the brain and spinal cord.

Management

Surgical Intervention

Procedure: laminectomy and closure of the open lesion or removal of the sac usually can be done soon after birth.

Purpose:

To prevent further deterioration of neural function.

To minimize the danger of rupture and infection, especially meningitis.

To improve cosmetic effect.

To facilitate handling of the infant.

Multidisciplinary Follow-Up for Associated Problems

A coordinated team approach will help maximize the physical and intellectual potential of each affected child.

The team may include a neurologist, neurosurgeon, orthopedic surgeon, urologist, primary care provider, social worker, physical therapist, occupational therapist, a variety of community-based and hospital staff nurses, and the child and family.

Numerous neurosurgical, orthopedic, and urologic procedures may be necessary to help the child achieve maximum function.

Prognosis

Influenced by the site of the lesion and the presence and degree of associated hydrocephalus. Generally, the higher the defect, the greater the extent of neurologic deficit and the greater the likelihood of hydrocephalus.

In the absence of treatment, most infants with meningomyelocele die early in infancy.

Surgical intervention is most effective if it is done early in the neonatal period, preferably within the first few days of life.

Even with surgical intervention, infants can be expected to manifest associated neurosurgical, orthopedic, or urologic problems.

New techniques of treatment, intensive research, and improved services have increased life expectancy and have greatly enhanced the quality of life for most children who receive treatment.

Complications

Hydrocephalus associated with meningocele; may be aggravated by surgical repair.

Scoliosis, contractures, and joint dislocation.

Skin breakdown in sensory denervated areas and under braces.

Nursing Assessment

Assess sensory and motor response of lower extremities.

Assess ability to void spontaneously, retention of urine, symptoms of UTI.

Assess usual stooling patterns, need for medications to facilitate elimination.

Assess mobility and use of orthoses, casts, and other special equipment.

Nursing Diagnoses

Neonates (Preoperative)

Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to impaired motor and sensory function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access