OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT

Common Nursing Assessment for Growth and Development

Endocrine dysfunction in children frequently leads to altered growth and development. Accurate nursing assessment can help detect variations in growth and developmental patterns, identify such factors as diet and medications that may have an impact on growth and development, and obtain information about compliance and understanding of treatment.

Evaluation of Growth Patterns

Perform frequent and accurate measurements of height and weight.

Accurately plot measurements on growth curve for absolute chronologic age.

Assess growth pattern for any deviation from the child’s percentile or from the parallel of the growth curve for age (includes both an upward as well as a downward deviation).

Calculate growth velocity—take the difference of current height from previous height and divide by the time period. Growth rate for a prepubertal child should be 2 to 3 inches (5 to 7 cm) on an annual basis.

Report any child whose pattern deviates from the expected pattern for age to health care provider.

General Health History

Dietary history—what is the child’s meal frequency, volume, and food preferences? Be vigilant while obtaining the history of a child when anorexia may be possible—growth velocity will usually be low, in addition to poor weight gain.

History of major illnesses or surgeries that have altered the child’s growth and development.

Family history—is there a family history of growth or developmental issues? Is there a family history of delayed puberty? Are family members unusually short or tall in stature, or is there obvious dysmorphology?

Clothing—outgrowing clothing and shoes?

Social history relative to friendships.

Academic and school performance—recent changes?

Activity—activities the child participates in? Intensity and type of exercise?

Medication History and Compliance

Is child on any steroid medications (such as prednisone) that would suppress growth? Inquire about over-the-counter medications or herbal supplementation.

When pubertal signs are present on physical examination, does child have access to any gonadal steroids (ie, birth control pills, anabolic steroids)?

Do child and family understand treatment medication indication and usage instructions?

Are child and family compliant with medications according to dose, frequency, and route? Is medication stored properly?

If taking oral medication, is it being taken with food, if indicated? If pills are being chewed, are teeth being brushed soon after, which could be rinsing out the medications?

If injectable, are injection sites being rotated appropriately? Review technique.

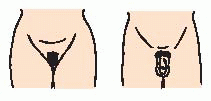

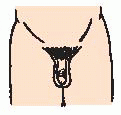

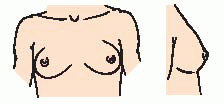

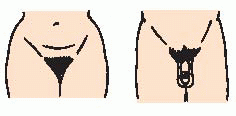

Physical Examination Relative to Development

Causes of Disorders of Growth and Stature

It is important to realize that growth and stature problems are caused by a wide variety of factors. Thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing can help reveal the underlying cause. Many of the disorders are associated with other anomalies, such as mental retardation, cardiac problems, metabolic issues, and secondary sex characteristic abnormalities. The cause may be treatable to resolve the growth problem, be amenable to growth hormone supplementation, or may be untreatable due to genetic cause.

Short Stature and Growth Failure

Genetic Causes

Familial short stature—short target height relative to U.S. standards; however, growth rate is normal.

Constitutional delay—short stature with retarded linear growth beginning in the first 3 years of life followed by short stature relative to peers; however, final height normal upon completion of pubertal development. Puberty is usually delayed.

Genetic disorders:

Dwarfism—multiple types and causes relative to chondrodysplasias.

Turner syndrome—occurs in about 1 in 2,500 female births. Characterized by short stature, ovarian dysgenesis (underdeveloped, degenerate ovaries), and, in some cases, unusual physical appearance (see

page 1799).

Russell-Silver syndrome—characterized by unilateral poor growth, short stature, characteristic facies, mental delays. Whenever unilateral change in growth is present, abdominal tumor needs to be ruled out.

Prader-Willi syndrome—rare syndrome characterized by below-normal intelligence, small stature, hypogonadism (see

page 37), failure to thrive in infancy followed by obesity and insatiable appetite, bizarre binge-type eating behaviors.

Down syndrome—occurs in 1 in 700 live births; characterized by growth retardation and mental retardation (see

page 1796).

Cystic fibrosis—occurs in 1 in 2,000 live births. In addition to respiratory and GI symptoms, growth retardation occurs (see

page 1508).

Nonendocrine Disorders

Glucocorticoid (prednisone) therapy for asthma, prevention of transplant rejection, adjunct medication in cancer chemotherapy.

Nutritional deficiency.

Psychosocial issues.

Chronic diseases—cardiovascular, renal, hematologic, pulmonary, malabsorptive disorders, inborn errors of metabolism.

Medical interventions—surgical tumor resection, radiation for brain tumors.

Tall Stature and Excessive Growth

Nonendocrine Disorders

Exogenous use of androgens (ie, testosterone injections):

Although stature and growth will initially be above the normal expected for age, ultimate height will be decreased due to undue advance of bone maturation at growth plate.

The child will ultimately end up shorter than genetically determined.

Sotos syndrome (cerebral gigantism)—usually large at birth with rapid growth in first year of life, intellectual impairment. Hypothesized to be a hypothalamic defect; normal endocrine function.

DISORDERS OF THE ANTERIOR PITUITARY

The anterior pituitary is under the control of the hypothalamus and secretes six specific hormones: GH, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and prolactin. GH is the only hormone that does not have a target gland to induce further hormonal secretion. Hypopituitarism is a deficiency of one, some, or all of the hormones secreted by the pituitary gland. With the exception of GH, decreased secretion results in hypofunction of the consequential target gland.

TSH deficiency, ACTH deficiency, and LH/FSH deficiency are discussed under disorders of the thyroid gland, disorders of the adrenal glands, and disorders of gonadal function, respectively.

Growth Hormone Deficiency

Insufficient secretion of GH is caused by lack of pituitary production or hypothalamic stimulation on the pituitary. Incidence is approximately 1 in 4,000 for classic GH insufficiency and is unknown for varying degrees of insufficiency.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

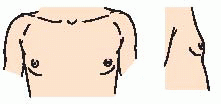

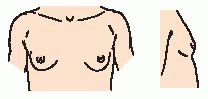

Clinical Manifestations

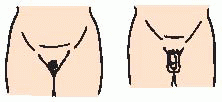

Hypoglycemia, prolonged jaundice, microphallus (small penis); usually in the neonate.

Growth velocity usually less than the 5th percentile for chronologic age.

Delayed skeletal maturation—bone age at least 1 year delayed from chronologic age.

“Pudgy” when the weight age (50% for weight) exceeds the height age (50% for height).

Frequently delayed eruption of primary and secondary teeth (not as severe as in hypothyroidism).

Delayed or lack of sexual development.

In young adulthood after epiphyseal fusion, the following symptoms may develop, requiring evaluation from an adult endocrinologist:

Altered body composition (increased fat mass, decreased lean body mass).

Reduced aerobic exercise capacity or performance.

Decreased muscle strength.

Abnormal blood lipid (fat and cholesterol) concentrations.

Decreased bone mineral density or content.

Impaired cardiac function.

Impaired health-related quality of life (low energy level, decreased physical mobility, difficulties with concentration and memory, increased emotional lability, irritability, difficulty relating to others, or increased social isolation).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Rule out organic, nonendocrine causes of short stature (ie, chronic illness, nutritional deficiencies, genetic disorders, psychosocial factors).

Calculate growth velocity. (Does growth pattern parallel or deviate from the growth curve?)

Bone age assessment—ascertain age of physical development; usually delayed.

General physical examination—physical development that of a younger-appearing child, microphallus in the neonate.

Chromosome testing of females (rule out Turner syndrome).

Thyroid function tests to rule out hypothyroidism.

GH secretion laboratory indicators: IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1), IGF-binding protein 3 are decreased. (Malnutrition can cause low IGF-1.)

Subnormal secretion of GH in response to two provocative stimuli:

Insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

Abnormal stimulatory response to arginine infusion, L-dopa, clonidine, or glucagon—all of which have specific actions resulting in GH secretion from pituitary. Pharmacologic agent is given, followed by blood sampling for GH response; GH levels less than 10 ng/mL are abnormal.

In the neonate with hypoglycemia, GH release is reduced at time of documented hypoglycemia (concomitant GH level relative to documented hypoglycemia is abnormally low).

GH has been associated with reduction in serum levels of free T4. Patients starting on GH should have their thyroid function monitored in the first 6 months of treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of head to rule out tumor (MRI is gold standard).

Management

Goal of treatment is to restore normal growth and development as well as to maximize growth potential and prevent hypoglycemia.

Replacement of deficiency uses recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid-derived GH given as subcutaneous injection.

Typical dose is 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg per week divided in six or seven doses weekly until final height is achieved. In treatment of Turner syndrome, dose is generally 0.375 mg/kg per week divided in doses as above. Note: Administration three times per week is not as effective as six to seven times per week.

Therapy is being recommended for adult replacement. Depending on the degree of insufficiency, continued treatment into adulthood may be useful. Dosing recommendations range from less than 0.006 mg/kg/day to as high as 0.0125 mg/kg/day after epiphyseal fusion has occurred.

Nursing Diagnoses

Delayed Growth and Development related to lack of GH.

Impaired Social Interaction related to short stature and peer acceptance.

Chronic Low Self-Esteem related to discordant expectations by peers and adults.

Nursing Interventions

Providing Education and Evaluation

Teach method of injecting GH through written and verbal instructions. Give demonstration and encourage return demonstration.

Encourage rotation of sites in the subcutaneous tissue of the upper arms or thighs to prevent skin irritation and hypertrophy.

Document growth every 3 to 6 months while on therapy.

If poor growth response, evaluate for appropriate dose, compliance, and injection technique. There may be initial “catch-up” growth that will be exhibited by a growth velocity above normal.

Instruct patient and family to report adverse effects: severe headache, hip and knee pain, limp, increased thirst and urination.

Encouraging Social Interaction

Encourage the child to verbalize feelings regarding short stature.

Have the child describe what he or she likes about certain people to help the child understand that friendships and social value are based on personality traits rather than absolute height.

Suggest involvement in activities that do not use height as an advantage, such as music, art, and gymnastics.

Ask the child to identify behaviors that may deter socialization (may or may not be related to short stature) and find ways to change behavior.

Strengthening Self-Esteem

Help child and parents to identify age-appropriate behaviors and develop a plan for maintaining consistent behaviors in the home and socially.

Make sure parents have realistic expectations of child.

Encourage the use of positive feedback rather than punishment.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Become familiar with the GH preparation being used and develop a teaching plan for home injection (mixing and injection technique). Provide periodic evaluation and ongoing support.

If home injections are difficult relative to family learning or parental availability, attempt to include school nurse in administering daily injections.

Review storage and stability of GH product relative to manufacturer’s specifications for the home as well as use in travel.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Tell child and family that short stature is not a “disease.”

Growth often catches up with peers usually when peers have stopped growing.

After initial startup of treatment, growth rate should be 4 to 5 inches (10 to 12 cm)/year in year 1 and 2¾ to 3½ inches (7 to 9 cm)/year thereafter.

Treatment is not to make child tall; rather, its purpose is to optimize final height potential.

Review medication dosage and injection technique periodically.

Tell family to think of GH as a replacement that is essential rather than a medication; therefore, it should always be given regardless of illness or other medication therapies.

Encourage regular follow-up for growth evaluation and maintenance of therapy.

Discuss potential lifelong therapy, which may be necessary depending on the degree of deficiency. Many hypopituitary patients require lifelong replacement therapy.

Recommend counseling about probable infertility for female with Turner syndrome. This should be done with a genetic counselor, if available.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Growth rate in initial 2 years of therapy should be two to four times pretreatment growth velocity with final gain of one to two standard deviations in height.

Child reports interest in school activities and playing with friends.

Parents report more positive behavior relative to self-esteem.

DISORDERS OF THE POSTERIOR PITUITARY

The posterior pituitary is under the control of the hypothalamus and secretes two hormones, vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone [ADH]) and oxytocin. Abnormality of ADH function is the most common disorder seen in children. The function of ADH is to conserve water at the distal tubules and collecting ducts of the kidney and to act on smooth muscle to increase blood pressure (BP).

Diabetes insipidus

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is failure of the body to conserve water due to a deficiency of ADH, decreased renal sensitivity to ADH, or suppression of ADH secondary to excessive ingestion of fluids (primary polydipsia).

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The function of water metabolism in the body is to maintain a constant plasma osmolality near the mean level of 287 mOsm/kg.

Intake and output of water are governed by the centers in the hypothalamus to control thirst and synthesis of ADH.

Thirst ensures adequate intake of water and ADH prevents water loss through the kidney.

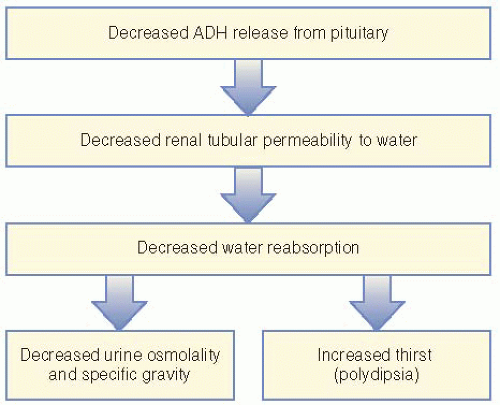

Patients with DI are unable to produce appropriate levels or action of ADH, leading to polyuria, increased plasma osmolality, and increased thirst (see

Figure 50-1).

Classified as central or nephrogenic DI:

Central DI—low levels of ADH; may be congenital or acquired.

Congenital causes—CNS defects, hereditary.

Acquired causes—CNS tumors, head trauma (orbital trauma), infections, vascular disorders, idiopathic.

Nephrogenic DI—renal unresponsiveness to vasopressin; usually caused by chronic renal disease.

Acquired causes—dietary abnormalities such as primary polydipsia, decreased sodium chloride intake, severe protein restriction or depletion, sickle cell disease, drugs (alcohol, lithium, diuretics, medications such as tetracycline).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Tests document inability to produce ADH in the face of hyperosmolality of plasma.

Urine-specific gravity, sodium, and osmolality are decreased.

Serum osmolality and sodium are elevated.

Serum measurement of ADH is low in conjunction with high plasma osmolality.

Water deprivation test (potentially dangerous):

Fluids are restricted and the urinary volumes and concentrations are monitored hourly along with the child’s weight.

Test is terminated if child loses more than 3% to 5% of body weight. Serum sodium and osmolality are measured at completion of test and are high; urine osmolality remains lower.

Test is completed by giving the child a dose of ADH, which should stop the abnormal diuresis. If it does not, child may have nephrogenic DI.

Assess for underlying cause:

Management

Daily replacement of ADH using desmopressin (DDAVP), a synthetic analogue.

Available as a metered nasal spray, measured insufflation (nasal) tube, or tablets. In children with cleft lip and palate, sublingual administration has been shown to be effective.

Thiazide diuretics in nephrogenic DI.

Nursing Assessment

Assess children with complaints or behaviors of polyuria and polydipsia for dehydration.

Obtain a thorough history of symptoms and behaviors—specific attention to changes in sleep patterns (may be caused by enuresis) and choices of fluids, including sources of water (eg, does child drink from toilet bowls or dog dishes?).

Evaluate height and weight—assess for weight loss related to possible decrease in calories due to excessive drinking, which decreases appetite.

For the child on treatment, assess for hydration status. Obtain history of fluid intake and output from the parents to assess appropriate dosage, frequency, and administration of medication.

Nursing Diagnoses

Deficient Fluid Volume related to disease process.

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements due to fluid preference over food.

Disturbed Sleep Pattern related to nocturia and enuresis.

Nursing Interventions

Regaining Fluid Balance

Assess for and teach parents assessment of dehydration—dry mucous membranes, weight loss, increased pulse, listlessness or irritability, sunken fontanelle in infants, fever, poor skin turgor.

Administer fluid via intravenous (IV) route, as ordered, if acutely dehydrated.

Monitor intake and output and teach parents to maintain record of fluid intake and output in child. Reduced output may require restriction of fluids to prevent hyponatremia if overdosage of DDAVP is suspected.

Keep record of daily weight.

Family education of DDAVP administration includes nurse demonstration and family administration. Proper management should eliminate symptoms.

Teach parents to provide free access to fluid (water) sources at all times. However, caution parents that child is unprotected from water excess.

Calculate rough estimated total daily (24-hour) fluid requirements based on body size to assess fluid replacement versus excess: 100 mL/kg for first 10 kg of body weight, 50 mL/kg for second 10 kg of body weight, 20 mL/kg for each additional kilogram.

Maintaining Adequate Nutrition

Make sure that adequate formula is ingested between plain water bottles.

For older child, provide liquid nutritional supplements.

Stress to parents or caregivers the importance of providing nutritional requirements with fluids to ensure meeting caloric demands for growth.

Consult with dietitian about need for vitamin or other supplements.

Monitor length and weight and developmental milestones at regular intervals.

Normalizing Sleep Pattern

Ensure adequate evening administration of DDAVP to prevent nighttime water craving and enuresis.

Suggest the use of diapers at night and plastic padding on bed to make controlling bedwetting easier until optimum management of condition is attained.

Encourage easy access to fluids and toilet or commode for older child during night.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Teach family insufflation method (for infants and young children):

Correct dose is measured and drawn up into catheter.

Catheter is inserted into patient’s nostril.

Parent or patient inserts other end of catheter into mouth and gently blows.

Older children may be able to inhale the solution.

Advise that nostrils should be as clear as possible before administration of dose.

Advise that, if dose is thought to be swallowed, do not readminister due to potential overdosage. Split the dose into both nares if swallowing is occurring.

Tell family to store drug away from heat and direct light and moisture (not in bathroom).

Advise parents that children should wear MedicAlert bracelet for DI.

Tell parents that school personnel should be aware of condition and symptoms needing attention (water intoxication).

Advise routine follow-up; treatment may be temporary or lifelong, depending on cause.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

No signs of dehydration; intake equals output.

No weight loss, growth curve maintained.

Child sleeping through night.

DISORDERS OF THE THYROID GLAND

Under hypothalamic-pituitary regulation, the thyroid gland secretes thyroxine (T

4) and triiodothyronine (T

3). The action of these hormones promotes cellular growth and differentiation, protein synthesis, and lipid metabolism (cholesterol turnover). Lack of adequate thyroid hormones can affect mental development and sexual maturity. Function of the thyroid gland is controlled by a negative feedback mechanism utilizing TSH released from the pituitary gland (see

Figure 50-2). Disorders of the thyroid gland are broadly classified as hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is low circulating level of T4. Congenital hypothyroidism occurs in 1 in 4,000 live births.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Circulating levels of T4 are dependent on hypothalamic-pituitary stimulation (TRH [thyrotropin-releasing hormone]/TSH) of the thyroid gland.

Low levels of T4 cause an increase in TSH level.

Absent or decreased levels of T4 result in abnormal development of the CNS of the neonate.

In older children, hypothyroidism results in a decrease in metabolism, growth, and physical maturation.

Congenital causes:

Thyroid agenesis or dysgenesis.

Hormone synthesis defect.

Maternal thyroid antibodies crossing placenta.

Iodine deficiency.

Drug-induced destruction (thioamides for treatment of hyperthyroidism, iodide excess).

Peripheral T4 resistance.

Acquired (postnatal) causes:

Autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis).

Radiation.

Surgical ablation (thyroidectomy).

Antithyroid drugs.

Iodine deficiency.

Central hypothyroidism (TRH/TSH deficiency).

Clinical Manifestations

Neonates

Very subtle physical signs, if any.

Markedly open posterior fontanelle.

Prolonged physiologic jaundice.

Feeding difficulties.

Skin cool to touch, mottled.

Poor muscle tone—hypotonia, umbilical hernia.

Acquired Cases

Growth retardation—slow growth rate, increased weight gain.

Lethargy—obedient, nonaggressive, somnolent.

Cold intolerance.

Possible poor school performance.

Constipation.

Evidence Base

Evidence Base NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT Evidence Base

Evidence Base Evidence Base

Evidence Base NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT