Pediatric Integumentary Disorders

BURNS

Management of Burns in Children

Burns are common childhood injuries. They may be caused by heat, electrical energy, or chemicals. Long-term surgical and psychological sequela often follow a burn injury and may include reconstruction and issues related to posttraumatic stress disorder. Very serious burns may include:

Partial-thickness (second-degree) burns of 12% to 15% or more of body surface area and full-thickness burns.

Burns of face, hands, feet, perineum, or joint surfaces.

Electrical burns.

Burns in the presence of other injuries.

Any burn that cannot be cared for adequately at home.

Epidemiology

Burns are the third leading cause of accidental deaths in childhood, with the highest incidence of burns occurring in children younger than age 5.

Children at high risk are of lower socioeconomic status and of single parents. However, any child, supervised or unsupervised, is at risk for a burn injury.

Scalds are the leading cause of injury in children, followed by flame burns.

Burns from a hot liquid are most common in children younger than age 3.

Tap water temperature above 120° F (48.9° C) (at 130° F [54.4° C]) takes only 30 seconds to produce a full-thickness injury in adult skin—less time in the very young; at 155° F (68.3° C), tap water will cause a full-thickness injury in a child in 1 second.

Child left unsupervised in tub turns on hot water tap.

Child placed in tub of hot water that has not been tested.

Spilling of hot liquid, such as coffee or tea, on child. Spilling occurs especially when pot handles stick out on top of stove, when hot liquids and foods are removed from microwave oven, and when child grabs or pulls items from surfaces.

Ingestion and aspiration of hot foods and liquids from microwave oven as well as scald burns to skin and palate from hot formula.

Burns from open flames:

House fires.

Child climbing on stove, resulting in ignited clothing.

Children playing with lighters, especially 3- to 10- year-olds.

Playing or working with gasoline.

Automobile accidents with subsequent fire.

Juvenile fire-setters.

Electrical burns are most common in toddlers and adolescents and may be caused by:

Child playing with electrical outlets or appliances.

Child playing with extension cords; children commonly bite through the cord.

Child playing on railroad tracks; climbing trees and touching high-tension wires; lightning.

Other causes:

Caustic acid or alkali burns, often of the mouth and esophagus.

Chemical burns of the skin—child playing with gasoline or chemical cleaning agents.

Burns inflicted on the child as a result of neglect or abuse (immersion and contact burns most common).

Smoke inhalation and inhalation from products of combustion of synthetics, such as plastics and rayon; may yield cyanide, formaldehyde.

Radiation burns—sunburn most common, may be secondary to cancer radiation therapy.

Contact burns from touching hot surfaces, such as radiators, wood-burning stoves, fireplaces, or open ovens.

Fireworks burns, typically as a result of misuse and lack of adult supervision; may be combined with explosive hand injuries.

Friction burns such as those seen with exercise treadmills in the home.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTWith combined injury, management of trauma takes precedence over the burn.

Clinical Manifestations

Characteristics of Burn Wounds

See page 1184 for characteristics of superficial, partial-thickness, and full-thickness burns.

Electrical burns:

Especially of the mouth in child younger than age 2; may chew or suck on live wire.

Are progressive and may take up to 3 weeks to fully manifest the extent of injury.

Symptoms of Shock

Symptoms of hypovolemic shock are dependent upon the size and thickness of the burn. Hypovolemic shock may develop in large surface size burns within the first 1 to 2 hours of the injury.

Rapid pulse, low blood pressure.

Subnormal temperature.

Pallor, cyanosis, prostration.

Failure to recognize parents or other familiar people.

Poor muscle tone; flaccid extremities.

Symptoms of Toxemia

Symptoms may develop 1 to 2 days after burn.

Prostration, fever, rapid pulse.

Glucosuria, decreased urine output.

Vomiting, edema.

These symptoms may progress to coma or death.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTThe fever of toxemia is not to be confused with expected “burn fever,” which may be as high as 103° F (39.4° C) because of the hypermetabolic state.

Upper Respiratory Tract Injury

Causes inflammation or edema of the glottis, vocal cords, and upper trachea and is characterized by symptoms of upper airway obstruction and immediate attention to securing and maintaining the airway takes precedence over the burn injury. Signs of inhalation are:

Dyspnea, tachypnea, hoarseness.

Stridor, substernal and intercostal retractions, nasal flaring.

Restlessness, drooling, cough, increasing hoarseness.

Carbonaceous sputum.

Facial burns and/or edematous lips.

Black nasal or oral secretions.

Hypoxemia.

History of burn within a closed space.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTIncreasing hoarseness, drooling, and stridor are leading indicators for immediate intubation.

Smoke Inhalation

Smoke inhalation may cause no initial symptoms other than mild bronchial obstruction during the initial phase after the burn. Within 6 to 48 hours, the child may develop sudden onset of the following conditions:

Bronchiolitis.

Pulmonary edema (acute respiratory distress syndrome)—of noncardiac origin.

Severe airway obstruction.

Delayed damage: up to 7 days after the burn injury.

Suspicious Burns in Children

Mechanism of injury is an important assessment when a burn injury involves a child. If the mechanism of injury seems out of proportion to the injuries of the child, notification to law enforcement is mandated by all nursing practice acts. Be alert for the following characteristics that may require further investigation by law enforcement:

Burns in a pattern.

History and physical findings inconsistent with the burn injury.

Burn injuries incompatible with child’s developmental level.

Burn to buttocks, perineum, or genitals.

Burns involving immersion into hot water. Typical findings reveal the back of the knees will be spared of burn injury, with entire feet and lower legs burned.

Multiple and new and old burns in different stages of healing.

Burns that are circular in nature, likely due to cigarette burns.

Presence of other nonburn injuries such as bruises, scrapes, or previous fractures.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Calculation of the Burn Area

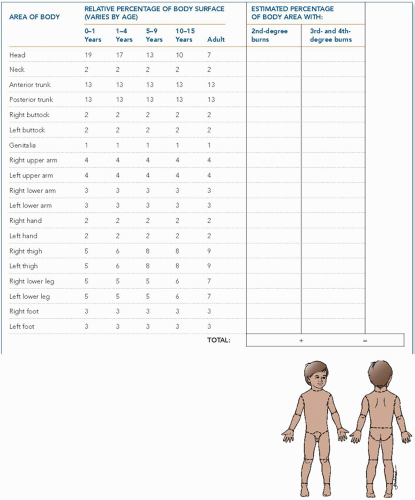

Rule of Nines (used in assessment of extent of burns in adults) has not proven to be exact when applied to young children; it may be acceptable to use in child older than age 10. It is not recommended for hospital use; the Lund and Browder chart is recommended. Total body surface area (TBSA) is based on age, thus compensating for changes in body surface area that change during growth (see Figure 55-1).

During infancy and early childhood, the relative surface area of different parts of the body varies with age.

The younger the child, the greater the proportion of the surface area is constituted by the head and the lesser the proportion of the surface area is constituted by the legs.

Figure 55-1. The Lund and Browder chart is used to determine the extent of burns in children because it is based on age, thus compensating for changes based on growth.

A rough estimate can be obtained by using the child’s hand (palm, with fingers extended), which is equal to 1%.

Categorization of Severity of Burn

Total area injured, depth of injury, location of injury.

Age of child.

Condition of patient (ie, level of consciousness). Confusion is the hallmark of an anoxic brain.

Medical history (ie, comorbidities, chronic disease).

Additional injuries.

Schematic Classification of Burn Severity

Minor burn—10% TBSA or less; first- and second-degree burn

Moderate burn:

10% to 20% TBSA; second-degree burn.

2% to 5% TBSA; third-degree burn not involving eyes, ears, face, genitals, hands, or feet or circumferential burns.

Major burn:

20% TBSA or greater; second-degree burn.

All third-degree burns greater than 10%; depending on age of child, 5% is sometimes used.

All burns involving hands, face, eyes, ears, feet, or genitals.

All electrical burns.

Complicated burn injuries involving fracture or other major trauma.

All poor-risk patients (ie, head injury, cancer, lung disease, diabetes).

Management

Fluid Resuscitation: Intravenous (IV) Fluid Replacement

Note: Controversy exists regarding fluid resuscitation solution and amount. Not all pediatric patients require fluid resuscitation. Children with burns 15% TBSA or less may be treated with oral rehydration therapies and supplemental maintance IV fluids.

Fluid loss from transcapillary leakage is greatest during the first 12 hours after injury and diminishes to almost zero 12 to 24 hours after injury. Fluid loss after 48 hours is due to vaporization of water from the wound.

Replacement usually consists of lactated Ringer’s solution, an isotonic electrolyte solution. Lactated Ringer’s solution has a much lower sodium content than 0.9% saline (130 mEq/L vs. 154 mEq/L), has a much higher pH (6.5 vs. 6.0), and has 28 mmol/L of lactate, which is used as a buffering agent.

The Consensus formula is commonly used to determine the fluid needed for resuscitation for burns greater than 15% TBSA (see page 1185). Children age 6 months to 5 years should receive a maintenance containing formula with dextrose to prevent hypoglycemia (5% dextrose or D5LR).

One half of the requirements are given during the first 8 hours.

The remainder is given over the next 24 hours

In children, the second day’s crystalloid consists of the maintenance requirements; 5% dextrose and 0.45% normal saline or 5% dextrose and 0.2% normal saline is used instead of 5% dextrose solution. Colloid is per Consensus formula.

Burn Treatment

Burns are most commonly treated by the closed method. However, dependent on the location of the burn a combination technique using both open and closed methods may be necessary.

Using the closed method is preferred as it allows children to be more mobile when a burn injury is covered and because they experience less pain.

Hydrotherapy is the treatment of choice for cleaning wounds. Isotonic saline rather than water may be needed for large wounds and small children. A large stainless steel tub, commonly with a one-use-only tub liner, is used to ensure a clean environment during the treatment. During a tub treatment, children should be encouraged to participate with washing off cream whenever possible. A gentle soap or shampoo can be used to wash the burned and nonburned parts of the body and hair. Tub or shower treatments are usually done daily unless a longer-acting dressing is in place between hydrotherapy sessions.

The use of a hand-held shower to facilitate the loosening and removal of sloughing tissue, eschar, exudate, and topical medications is gaining popularity. The shower—water about 90° F (32.2° C)—flows over the child; debridement is then performed.

Use pharmaceutical and psychological interventions, unique to each child and appropriate for their developmental stage and comfort needs, to ensure appropriate pain and anxiety management.

See page 1184 for wound cleaning and debridement, hydrotherapy, topical antimicrobials, surgical management, and burn wound grafting. It is important to use bacitracin ophthalmic ointment on a child’s face because touching or rubbing the face may get ointment into the eyes. Topical bacitracin will cause conjunctivitis if it gets into the eyes.

Complications

Vary according to severity of burn injury; commonly occur, especially with severe burn injury.

Acute

Infection; burn wound sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI), phlebitis, toxic shock syndrome.

Curling’s (stress) ulcer, GI hemorrhage; rarely seen now that histamine-2 (H2) blockers are commonly used prophylactically, especially in burns greater than 20% TBSA.

Acute gastric dilation, paralytic ileus; occurs especially in child younger than age 2 with greater than 20% injury and develops early in postburn period, lasting 2 to 3 days.

Renal failure.

Respiratory failure; severe inhalation injury is the insult most likely to cause death.

Postburn seizures.

Hypertension.

Central nervous system dysfunction.

Vascular ischemia.

Anxiety and complex pain (acute to chronic presentations).

Anemia and malnutrition; may resolve when the burn area is covered.

Constipation and fecal impaction.

Labile moods secondary to hospitalization, repeated procedures, and changing body image.

Long Term

Growth and development delays secondary to malnutrition, hospitalization, complexities of injury and recovery.

Developmental regression.

Scarring, disfigurement, and contractures.

Impact of psychological trauma.

Nursing Assessment

Initially, perform emergency assessment of the burn patient to determine priorities of care.

Airway, breathing, and circulation: airway may be compromised with inhalation injury.

Extent of burn injury.

Additional injuries. (Although establishing a patent airway always comes first, trauma takes precedence over the burn.).

Obtain a history of the injury—for example, when the injury occurred; what first aid was given; location of the child; if smoke was present, if child was in a closed space; who was supervising the child; what the specific mechanism of injury was; what other factors need to be considered in terms of the context of the injury; consider if additional injuries may exist.

Obtain a complete medical history, including childhood diseases, immunizations (especially tetanus status), current medications, allergies, recent infections, general health and developmental status.

Assess level of pain and emotional status; provide pain relief and reassurance while performing assessment and determining priorities.

Subsequently, focus assessment on fluid volume balance, condition of the burn wounds, and signs of infection (burn wound, pulmonary, urinary).

Remain vigilant for signs of sepsis. The American Burn Association 2007 consensus guidelines provide clear definitions for sepsis and common infections in burn patients, but it’s not perfect. Additional markers such as procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be used. Sepsis occurs in children when at least three of the following occur:

Temperature above 102.2° F (39° C) or below 97.7° F (36.5° C).

Progressive tachycardia more than 2 standard deviations (SD) above age-specific norms.

Progressive tachypnea more than 2 SD above age-specific norms.

Thrombocytopenia (not applicable until 3 days after initial recuscitation) less than 2 SD below age-specific norms.

Hyperglycemia (in the absence of preexisting diabetes mellitus).

Untreated plasma glucose greater than 200 mg/dL.

Insulin resistance.

Inability to continue enteral feedings for more than 24 hours.

Abdominal distention.

Enteral feeding intolerance.

Uncontrollable diarrhea.

In addition, it is required that infection be documented by positive culture, pathologic tissue source identified, or clinical response to antimicrobials observed.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseGreenhalgh, D. G., Saffle, J. R., Holmes, J. H. IV, et al. (2007). American Burn Association Consensus Conference to define sepsis and infection in burn. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation, 28(6), 776-790.

Hogan, B. K., Wolf, S. E., Hospenthal, D. R., et al. (2012). Correlation of American Burn Association sepsis criteria with the presence of bacteremia in burned patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation, 33(3), 371-378.

Nursing Diagnoses

Decreased Cardiac Output related to fluid shifts and hypovolemic shock.

Risk for Infection related to altered skin integrity, decreased circulation, and immobility.

Impaired Gas Exchange related to inhalation injury, pain, and immobility.

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to hypermetabolic response to burn injury.

Dysfunctional gastrointestinal motility related to paralytic ileus and stress.

Ineffective Peripheral Tissue Perfusion related to edema and circumferential burns.

Risk for Imbalanced Fluid Volume related to fluid resuscitation and subsequent mobilization 3 to 5 days postburn.

Impaired Skin Integrity related to burn injury and surgical interventions (donor sites).

Impaired Urinary Elimination related to indwelling catheter.

Ineffective Thermoregulation related to loss of skin microcirculatory regulation and hypothalamic response.

Impaired Physical Mobility related to edema, pain, dressings and splints.

Acute Pain related to burn wound and associated treatments.

Disturbed Body Image related to cosmetic and functional sequelae of burn wound.

Fear and Anxiety related to pain, treatments, procedures, and hospitalization.

Impaired Parenting related to crisis situation, prolonged hospitalization, and disfigurement.

Disturbed Sleep Pattern related to unfamiliar surroundings and pain.

Nursing Interventions

Supporting Cardiac Output

Be alert to the symptoms of shock that occur shortly after a severe burn—tachycardia, hypothermia, hypotension, pallor, prostration, shallow respirations, anuria.

Monitor the administration of IV fluids because major burns are followed by a reduction in blood volume due to outflow of plasma into the tissues.

Maintain and record intake and output to provide an accurate measure of volume.

Record time and amount of all fluids given.

Measure urine output every hour and report diminished output, as ordered (0.5 mL/kg/hour is considered minimally acceptable urine output; however, 1 mL/kg/hour is preferable).

Check urine-specific gravity to determine concentration or dilution.

With severe burn injuries, insert an indwelling catheter.

Weigh patient daily to help evaluate fluid balance.

Monitor sensorium, pulse, pulse pressure, capillary refill, and blood gas values.

Provide a rich oxygen environment to combat hypoxia, as necessary.

Monitor electrolyte and hematocrit results as a guide to fluid replacement.

Maintain a warm, humidified ambient environment (especially with burns of 20% TBSA) to maintain body temperature and decrease fluid needs.

Preventing Infection

Wash hands with antibacterial cleansing agent before and after all patient contact and use appropriate precautions.

Use barrier garments—isolation gown or plastic apron— for all care requiring contact with the patient or the patient’s bed.

Cover hair and wear mask when wounds are exposed or when performing a sterile procedure.

Use sterile examination gloves for all dressing changes and all care involving patient contact.

Be alert for reservoirs of infection and sources of cross-contamination in equipment, assignment of personnel.

Observe burn wounds with each dressing change: assess drainage for color, odor, and amount; necrosis; increase in pain; and surrounding erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness, which may indicate infection.

Administer topical antimicrobials and systemic antibiotics, as ordered.

Provide meticulous skin care to prevent infection and promote healing.

Be alert for early signs of septicemia, including changes in mentation, tachypnea, and decreased peristalsis as well as later signs, such as increased pulse, decreased blood pressure (BP), increased or decreased urine output, facial flushing, increased and later decreased temperatures, increasing hyperglycemia, and malaise. Report to health care provider promptly.

Obtain serial cultures, as ordered.

Obtain urine, sputum, and blood cultures for two or more consecutive temperatures of 103° F (39.4° C) or a single temperature of 104° F (40° C).

Pan culturing (urine, wound, blood, and sputum) may be ordered.

Promote optimal personal hygiene for the patient, including daily cleansing of unburned areas, meticulous care of teeth and mouth, shampooing of hair every other day, and meticulous care of IV and urinary catheter sites.

Prevent the child from scratching by administering antipruritics and applying protective devices to his or her hands.

Be alert for the development of pneumonia or UTI related to immobility and invasive procedures. Encourage coughing, turning, deep breathing, ambulation, and early discontinuation of indwelling catheter to minimize complications.

Ensure that appropriate nutrition and enteral feeding are in place within 6 to 8 hours of injury to prevent translocation of bacteria in the gut.

Administer tetanus prophylaxis based on immunization history.

If primary series complete (or at least three doses of tetanus toxoid obtained) and last injection within past 5 years, it is not necessary.

If at least three doses obtained and last injection more than 5 years, give tetanus toxoid.

If two or fewer doses obtained, give tetanus immunoglobulin and tetanus toxoid.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTEven with meticulous skin care, the burn wound is fully colonized in 3 to 5 days. A warm, moist environment becomes an excellent medium for bacterial growth, especially of Pseudomonas.

Optimizing Gas Exchange

Be alert for and report symptoms of respiratory distress— dyspnea, stridor, tachypnea, restlessness, cyanosis, coughing, increasing hoarseness, drooling.

Administer supplemental humidified oxygen.

Monitor arterial blood gas (ABG) levels as necessary.

Evaluate the carboxyhemoglobin on ABG results (due to inhalation of carbon monoxide, a product of combustion) and be prepared to support ventilation if signs of hypoxemia and respiratory failure develop.

Assist with pulmonary function and bronchoscopy, as indicated.

Have intubation supplies readily available. If unable to intubate the child, then tracheostomy may be necessary. If unable to extubate in 14 to 21 days, then may be converted to tracheostomy for continuous pulmonary management. The current trend is to use the earlier time frame.

Prevent atelectasis and pneumonia through chest physical therapy, postural drainage, meticulous pulmonary technique, and, if indicated, tracheostomy care.

Ensuring Adequate Nutrition for Healing and Growth Needs

Be aware that hypernutrition is important because of the extreme hypermetabolism related to large burn injuries.

Twice the predicted basal metabolic rate in calories, based on ideal weight, may be necessary. Caloric recommendation is 1,800 kcal/m2 total body surface for maintenance, plus 2,000 kcal/m2 of burned surface area.

Hypermetabolic state generally subsides when the majority of the wounds are grafted or healed.

High caloric intake to support hypermetabolic state; protein synthesis; calories should come from carbohydrates.

High-protein intake to replace protein lost by exudation; support synthesis of immunoglobulins and structural protein; prevent negative nitrogen balance.

Vitamin and mineral supplement needed, particularly vitamins B and C, iron, and zinc.

Maintain ambient temperature at 82.4° F to 90° F (28° C to 32.2° C) to minimize metabolic expenditure by maintaining core temperature.

Minimize anorexia to increase caloric intake.

Offer small amounts of food, perhaps four to five feedings rather than three per day.

Give choice of foods; determine favorites.

Provide high-calorie, high-protein oral or nasogastric (NG) supplementation, as necessary.

Consider long-term use of G-tube or NJ-tube for supplemental nutrition.

Make meals a pleasant time, unassociated with treatments or unpleasant interruptions. Maintain oral intake as much as possible.

Monitor dietary compliance with dietary goals and adjust, as needed.

Administer total parenteral nutrition, if necessary.

Administer serum albumin or fresh frozen plasma to combat hypoalbuminemia when burn area exceeds 20% TBSA.

Monitor nutritional status through weight gain, wound healing, serum transferrin, and serum albumin.

Relieving Gastric Dilation and Preventing Stress Ulcer

Be alert for the development of gastric distention, especially with burns greater than 20% TBSA, associated injury, or tachypnea.

Maintain nothing-by-mouth status if distention or decreased bowel sounds develop.

Insert NG tube, as indicated, to prevent vomiting, aspiration, and paralytic ileus.

Monitor the return of bowel sounds after NG extubation and before reinstituting oral feeding.

Administer H2-blockers such as cimetidine to prevent Curling’s ulcer development.

Promoting Peripheral Perfusion

Remove all jewelry and clothing.

Elevate extremities.

Monitor peripheral pulses hourly. Use Doppler, as necessary.

Prepare the patient for escharotomy if circulation is impaired.

Avoid tight constrictive dressings.

Observe for and report signs of thrombophlebitis or catheterinduced infections.

Facilitating Fluid Balance

Titrate fluid intake as tolerated. The initial resuscitation formula is only a guide.

Maintain accurate intake and output records.

Weigh the patient daily.

Monitor results of serum potassium and other electrolytes.

Be alert to signs of fluid overload, especially during initial fluid resuscitation and immediately afterward, when fluid mobilization is occurring.

Administer diuretics, as ordered.

Protecting and Reestablishing Skin Integrity

Cleanse wounds and change dressings twice daily. Use an antimicrobial solution or mild soap and water. Dry gently. This may be done in the hydrotherapy tank, bathtub, shower, or at the bedside.

Perform debridement of dead tissue at this time. May use gauze, scissors, or forceps, as appropriate. Try to limit time to 20 to 30 minutes depending on the patient’s tolerance. Additional analgesia may be necessary.

Apply topical bacteriostatic agents, as directed. Cream or ointment is applied 1 1/8-inch (3-mm) thick.

Dress wounds, as appropriate, using conventional burn pads, gauze rolls, or any combination. Dressings may be held in place, as necessary, with gauze rolls or netting.

For grafted areas, use extreme caution in removing dressings; observe for and report serous or sanguineous blebs or purulent drainage. Redress grafted areas according to facility protocol.

Observe all wounds daily and document wound status on the patient’s record.

Promote healing of donor sites by:

Preventing contamination of donor sites that are clean wounds.

Opening to air for drying postoperatively if gauze or impregnated gauze dressing is used. If exudate occurs after the first 24 hours, swab the area for culture and apply an antimicrobial topical cream. If the culture is positive, treatment will be in accord with sensitivities.

Following health care provider’s or manufacturer’s instructions for care of sites dressed with synthetic materials.

Allowing dressing to peel off spontaneously.

Cleansing healing donor site with mild soap and water when dressings are removed; lubricating site twice daily and as needed.

Inspect unburned skin carefully for signs of pressure and breakdown.

Preventing Urinary Infection

Maintain closed urinary drainage system and ensure patency. Use a catheter impregnated with an antimicrobial agent whenever possible.

Frequently observe color, clarity, and amount of urine.

Empty drainage bag per facility protocol.

Provide catheter care per facility protocol.

Encourage removal of catheter and use of urinal, bedpan, or commode as soon as frequent urine output determinations are not required.

Promoting Stable Body Temperature

Be efficient in care; do not expose wounds unnecessarily.

Maintain warm ambient temperatures.

Use radiant warmers, warming blankets, or adjustment of the bed temperature to keep the patient warm.

Obtain urine, sputum, and blood cultures for temperatures above 102° F (38.9° C) rectal or core temperature or if chills are present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access