Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Disorders

COMMON PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS

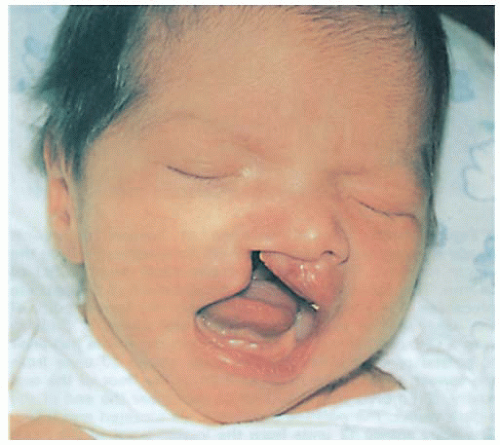

Cleft Lip and Palate

Cleft lip and palate are congenital anomalies, known as oral-facial clefts, resulting in structural facial malformation. These defects are usually present in early fetal development, are one of the most common birth defects in the United States, and associated with any of more than 400 syndromes. The lip, or the lip and palate, fail to close in approximately 1 in every 1,000 neonates. This equals approximately 7,000 infants born each year in the United States. Infants born with both cleft lip and palate number 4,437 per year. Cleft lip and palate is most prevalent among Native Americans.

Cleft lip (with or without cleft palate) occurs more frequently in males and isolated cleft palate is more frequent in females. The chance of having a child with an oral-facial cleft increases if one or both parents have a defect and if there is a sibling born with a defect.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseParker, S. E., Mai, C. T., Canfield, M. A., et al. (2010). Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004-2006. Birth Defects Research, Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 88(12), 1008-1016.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseKohli, S. S., & Kohli, V. S. (2012). A comprehensive review of the genetic basis of cleft lip and palate. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 16, 64-72.

A failure of fusion of lip/palate tissue between 5 and 7 weeks of gestation, resulting in defect in morphogenesis. It involves patterns of DNA signaling, gene and biochemical organizers, nuclear and cellular differentiation, proliferation, and migration. A major impact is at the level of the neural crest cell.

Although the syndrome is not well understood, genetic/hereditary factors may play a role; a fetus with an affected parent or sibling has a 3% to 5% risk of being affected.

In 2004, a gene variant was identified as being a major contributor to oral-facial clefts. This gene variant may triple the risk of developing the defect in signaling and transcription proteins that are involved in development and differentiation. There is a 50% risk in monozygotic twins.

Environmental factors may include:

Vitamin B and folic acid deficiency. Some studies have shown that consumption of multivitamins with folic acid prior to conception and during the first trimester may lower the incidence of cleft lip and palate. A 2007 study by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences suggests taking a multivitamin containing 400 mcg of folic acid.

Medications taken during pregnancy, including antiseizure drugs and corticosteroids.

Maternal alcohol and smoking.

Infections.

Diabetes.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseGrosen, D., Bille, C., Petersen, I., et al. (2011). Risks of oral clefts in twins. Epidemiology, 22(3), 313-319.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseJia, Z. L., Shi, B., Chen, C. H., et al. (2011). Maternal malnutrition, environmental expo sure during pregnancy and the risk of non-syndromic orofacial clefts. Oral Diseases, 17(6), 584-589.

Types of Defects

Cleft lip—prealveolar cleft (see Figure 48-1):

Varies from a notch in the lip to complete separation of the lip into the nose.

May be unilateral or bilateral.

Failure of maxillary process to fuse with nasal elevations on frontal prominence; normally occurs during 5th and 6th weeks of gestation.

Merging of upper lip at midline complete between 7th and 8th weeks of gestation.

Isolated cleft palate—postalveolar cleft:

Cleft of uvula.

Cleft of soft palate.

Cleft of both soft and hard palate through roof of mouth.

Unilateral or bilateral.

Failure of mesodermal masses of lateral palatine process to meet and fuse; normally occurs between 7th and 12th weeks of gestation.

Submucous cleft:

Muscles of soft palate not joined.

Not recognized until child talks; cannot be seen at birth.

Pierre Robin syndrome—cleft palate, glossoptosis (tongue lays back on pharynx), and micrognathia (underdeveloped mandible):

This causes feeding difficulties, potential airway obstruction by tongue, slow weight gain, and ear infections.

By age 3 to 4 months, the mandible has grown enough to accommodate the tongue and respiratory difficulty is greatly diminished.

Clinical Manifestations

Physical appearance of cleft lip or palate:

Incompletely formed lip—varies from slight notch in vermilion to complete separation of lip.

Opening in roof of mouth felt with examiner’s finger on palate.

Eating difficulty:

Suction cannot be created for effective sucking.

Food returns through the nose.

Nasal speech.

Increased incidence of otitis media, which may lead to mild to moderate hearing loss.

Speech delay secondary to lip defect as well as related to chronic otitis media.

Dental problems.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAras, I., Olmez, S., & Dogan, S. (2012). Comparative evaluation of nasopharyngeal airways of unilateral cleft lip and palate patients using three-dimensional and two-dimensional methods. Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 49(6), e75-81.

Prenatal ultrasonography to detect cleft lips and some cleft palates in utero.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and three-dimensional computed tomography to evaluate extent of abnormality before treatment.

Photography to document the abnormality.

Serial x-rays before and after treatment.

Dental impressions for expansion prosthesis.

Genetic evaluation to determine recurrence risk.

Management

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseMcGrattan, K. E., & Ellis, C. (2013). Team oriented care for orofacial clefts: A review of the literature. Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal 50(1), 13-18.

Interdisciplinary approach begins early and continues into late adolescence. Craniofacial team consists of a plastic surgeon, otolaryngologist, pediatric dentist, prosthodontist, orthodontist, feeding specialist, speech pathologist, audiologist, geneticist, psychologist, and community health nurse. Each team member has a role at some point in the child’s care.

General management is focused on proper growth and nutrition, closure of the clefts, prevention of complications, oral-motor rehabilitation, and facilitation of normal growth and development of the child.

Patients with isolated cleft lips have a greater chance of overcoming feeding difficulties than those with combined defects.

The cleft lip is repaired before the palate defect, generally around age 3 months.

Techniques performed include the Millard repair, which results in a zigzag scar on the lip, or placement of sutures where the line of the columella would have been.

The surgical goals are adherence and the most cosmetically pleasing and naturally appearing lip.

Cleft palate repair may be done any time between ages 6 and 18 months. Surgery and timing is based on degree of deformity, width of oropharynx, neuromuscular function of palate and pharynx, and surgeon’s preference. Some children may require more than one reconstructive surgery.

Palatoplasty is the reconstruction of the palatal musculature.

The surgical goal is adherence, development of normal speech pattern, and safe/appropriate eating skills. Additionally, it should decrease the incidence of otitis media.

Surgery may be performed by craniofacial or plastic surgeon in conjunction with other specialists, including oral surgeon and dentist.

Complications

Respiratory distress.

Infection.

Palatal fistulas.

Dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

Bleeding.

Nursing Assessment

If the newborn has a cleft lip, assess for cleft palate by direct visualization and palpation with finger.

Obtain family history of cleft lip or palate.

Evaluate feeding abilities.

Effectiveness of suck and swallow.

Amount taken.

Vomiting, regurgitation, or formula coming from nose.

Observe for other syndromic features, such as small jaw, abnormal facies, micro/macrocephaly, heart murmur, anal-rectal defects.

Nursing Diagnoses

Ineffective Infant Feeding Pattern related to defect.

Risk for Infection related to open wound created by malformation, ear infections.

Risk for Impaired Attachment related to malformation and special care needs of the infant.

Risk for Aspiration related to tongue and palate deformities in Pierre Robin syndrome.

Deficient Knowledge related to home management of infant with cleft malformation.

Fear related to surgery.

Deficient Knowledge related to postoperative care.

Nursing Interventions

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseCleft Palate Foundation. (2012). Neonatal cleft lip and palate protocol: Instructions for hospital nurseries. Chapel Hill, NC: Author. Available: www.cleftline.org/healthcare-professionals/tips for-hospital-nurseries.

Maintaining Adequate Nutrition

Facilitate nutrition and speech therapy for all infants.

Encourage the mother to begin feeding the infant as soon as possible to enhance bonding and to strengthen the oral structures needed for mastication and speech production.

If sucking is permitted:

Encourage breastfeeding.

Encourage and demonstrate breast pump.

Use a soft nipple with crosscut to facilitate feeding.

If sucking is ineffective due to inability to create a vacuum, try alternate oral feeding methods.

Feeding devices include preemie nipple, crosscut nipple, NUK nipple, Ross Cleft Palate Nurser, Mead Johnson Cleft Palate Nurser, Pidgeon nipple bottle system, Haberman Feeder, or palatal obturator.

Avoid enlarging nipple holes due to infant’s inability to control flow of milk, which will result in choking. Crosscut nipples allow milk to flow only when infant squeezes the crosscut open.

Using a squeezable bottle (eg, Mead Johnson Cleft Palate Nurser) or plastic liner can be helpful by applying rhythmic pressure along with the infant’s normal sucking and swallowing.

Rubber-tipped asepto syringe or dropper; the rubber extension should be long enough to extend back into the mouth to prevent regurgitation through the nose. Direct tip to side of mouth and feed slowly.

Feed infant in an upright, sitting position or the upright side-lying position if airway support is needed. This decreases possibility of fluid being aspirated or returned through the nose or back to the auditory canal.

Feeding is usually easier if the nipple is angled to the side of the mouth away from the cleft so the infant’s tongue can press the nipple against the upper gum or dental arch.

Feed slowly over approximately 18 to 30 minutes. Feedings longer than 45 minutes expend too many calories and tire infant.

Smaller but more frequent feedings may be necessary if the infant tires or requires extended time to eat.

Burp frequently during feeding to decrease amount of air swallowed.

If micrognathia exists, use of the pinky finger under the chin for support aids in improved sucking ability.

Feed infant before he or she becomes too hungry. If the infant is too agitated, feeding becomes a problem.

Administer enteral tube feedings if nipple feeding is to be delayed.

Advance diet as appropriate for age and needs of infant. Eating usually improves when solids are introduced because they are easier for the infant to manipulate.

Assess and calculate adequate nutritional intake.

Preventing Infection

Protect child from infection so that surgery will not be delayed.

Use and teach good handwashing practice.

Avoid patient contact with anyone who has an infection.

Provide frequent assessment for otitis media.

Clean the cleft after each feeding with water and a cotton-tipped applicator.

Observe for fever, irritability, redness, or drainage around cleft and report promptly.

Monitor vital signs; report temperature greater than 101° F (38.3° C).

Promoting Acceptance and Adjustment

Show acceptance of the infant; maintain composure and do not show negative emotion when handling the infant. The manner in which the nurse handles the infant can make a lasting impression on the parents.

Support parents when showing a neonate for the first time. Demonstrate acceptance of the infant’s and the parents’ feelings. Parents may be grieving about the infant’s cosmetic imperfections and may harbor ambivalent feelings.

Offer information and answer any questions in a simple, matter-of-fact manner. The better informed the family, the easier it will be for them to see the infant as a normal child with a physical difference that will require surgery, dental work, and possibly speech therapy.

Be aware that the normal sequence of parental responses may include shock, disbelief, worry, grief, and anger and then proceed to a state of equilibrium and reorganization.

Encourage parental involvement in infant’s care: frequent holding, cuddling, and playing.

Preventing Aspiration and Airway Obstruction

Prevent respiratory obstruction by the tongue, especially on inspiration and when the infant is quiet.

Positioning: elevated and side-lying.

Tilt head back as tolerated by the infant, and elevate upper trunk slightly.

Tongue/lip suture may be placed by otolaryngologist to prevent the tongue from interfering with airway. Assess for slippage, infection, pain, interference with eating.

Suction nasopharynx, as needed.

Infants with Pierre Robin syndrome are at greater risk for airway compromise, especially when feeding.

Feeding can be done with a nursing bottle (feeding techniques similar to those used for cleft palate).

Generally use orthopneic position—vertical and slightly forward; this allows infant to push jaw forward to suck and allows the feeder a clear view of the infant.

Use gentle finger pressure at mandibular attachment to bring the jaw forward.

Preparing for Home Management

Prepare family for home feedings by providing several days to practice feeding and to become familiar with the infant’s feeding pattern.

Alert caregiver to difficulties with feeding and how to manage them.

Nasal regurgitation: feed in more upright position or stop feeding and allow the infant to cough and clear the airway; then continue with smaller feedings.

Respiratory distress: feed slowly, give smaller feedings. Observe for signs of aspiration, such as coughing, color changes, increased respiration, fever, and/or formula coming from nose.

Prolonged feeding: if oral feedings take longer than 20 to 30 minutes, energy expenditure increases. Smaller, more frequent feedings are indicated or enteral tube feeding supplements may be warranted.

Suggest that about 1 week before scheduled admission for surgery the mother begin using feeding techniques preferred by multidisciplinary team. Infants who feed well prior to surgery may do better postoperatively than poor feeders.

Encourage the parents to prepare siblings at home for the arrival of the infant. Suggest they show a picture of the new infant.

Offer parents available resources regarding children with cleft lip and palate.

Encourage parental involvement with local self-help groups that provide information and parent-to-parent contact.

Initiate referrals, as indicated, for additional support and financial assistance and early intervention programs.

Describe and reinforce surgical treatment plans to the parents to promote communication and hope.

Stress compliance with follow-up care with the pediatrician, plastic surgeon, dentist, orthodontist, psychologist, and speech therapist to prevent chronic otitis media, hearing loss, speech impairment, and emotional problems.

Initiate a community nurse referral to continue emotional support and teaching progress at home.

Providing Preoperative Care and Allaying Fear in the Child Undergoing Surgery

Prepare the infant or toddler for the postoperative experience to decrease fear and increase cooperation.

Practice the feeding measure that will be used postoperatively—cup, side of spoon, or syringe.

Use elbow immobilizers for short periods; allow the child to play with them and the caregiver to use them. Check your facility’s policy regarding the use of immobilizers because this is considered a form of restraint, but may be deemed medically necessary.

Demonstrate and practice mouth irrigation because it will be done postoperatively for cleft palate repair; allow the child to assist if age appropriate.

Prepare the parents emotionally for the postoperative appearance of the child.

Explain the use of the Logan bow (a curved metal wire that prevents stress on the suture line for cleft lip repair) and restraints.

Encourage a parent to be with the child, especially when awakening from anesthesia, to offer security and comfort.

Address and explain pain management, collaborating with the parents as to what comforts their child.

Providing Postoperative Care

Protect surgical site:

Apply elbow immobilizers to prevent hands from reaching the mouth while still allowing some freedom of movement;

follow your institution’s policy regarding medical restraints.

Assess the patient’s skin and/or intravenous (IV) line every 2 hours while the immobilizer is in place.

Remove the immobilizer to exercise the arms.

Do not allow anything in the child’s mouth, such as straw, eating utensils, or fingers.

Maintain adherence device: check that Logan bow or other device is intact and maintaining adherence of lip repair.

Prevent wetting tape or it will loosen.

Observe for and report bleeding or dislodgement of Logan bow.

Prevent the child from stressing the suture site—not crying, blowing, sucking, talking, or laughing.

Assess and manage pain.

Consult institution’s pain management team, if necessary.

Use pain medications appropriate for age, weight, and condition.

Use pain assessment tools appropriate for age (see page 1446).

Recognize signs of pain, such as crying, agitation, poor feeding, increased vital signs.

Discourage pacifiers until cleared by surgeon.

Encourage the mother to hold the infant, swaddle, use security/comfort items from home.

Positioning—elevated head of bed and side-lying.

An infant seat may be useful for variation of position, comfort, entertainment, and to prevent interference with suture line.

Provide for appropriate diversional activity, hanging toys, and mobiles.

If only cleft palate was repaired, child may lie on abdomen.

Monitor respiratory effort after cleft palate repair.

Be aware that breathing with a closed palate is different from the child’s customary way of breathing; the child must also contend with increased mucus production.

Provide humidified air, if needed, to provide moisture to mucous membranes that may become dry from mouth breathing.

Prevent infection.

Clean suture line after every feeding.

Gently wipe lip incision with cotton-tipped applicator and solution of choice, such as water, saline, or diluted hydrogen peroxide. Gently pat dry and apply antibiotic ointment or petroleum jelly, if ordered.

Rinse the mouth with water or offer a drink of water after each feeding.

Irrigate the mouth with normal saline solution or water after cleft palate repair. Technique may vary based on preference of surgeon. You can direct a gentle stream over the suture line using an ear bulb syringe with the child in a sitting position with head forward.

Avoid tension on the suture line during feeding for several days after lip repair.

Use dropper or syringe with a rubber tip and insert from the side to avoid suture line or to avoid stimulating sucking.

Use side of spoon. Never put spoon into the mouth.

Perform enteral tube feedings, if prescribed; usually this is last treatment of choice.

Advance slowly to nipple feeding, as directed. The infant should be able to suck more efficiently after the lip is repaired.

After palate repair, feed the child in the manner used preoperatively (cup, side of spoon, or rubber-tipped syringe). Never use straw, nipple, or plain syringe.

Consult with speech/occupational therapy if feeding/swallowing continues to be difficult.

Facilitate adequate nutrition.

Obtain nutrition consult, if indicated.

Diet progresses from clear liquids to full liquids to soft foods.

Soft foods are usually continued for about 1 month after surgery, at which time a regular diet is started, but excludes hard food.

Ensure that child is receiving adequate calories.

Weigh daily and plot on growth charts (www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/).

Early feeding intervention relates to appropriate growth.

Administer an antibiotic, if prescribed, to prevent infection as the mouth and skin contain bacteria.

Community and Home Care Considerations

As the patient’s advocate, alert members of the craniofacial team when a family is overwhelmed by too many appointments and interventions. Act as liaison to case manager, social worker, and home care agency.

Continue to assess weight gain, feeding behavior, overall development, parent-child bonding and interactions.

Advise the parents to discuss the child’s problem with teachers and other responsible adults in close contact with the child.

Aesthetic touch-up and bone graft surgery performed later may interfere with schooling.

Speech differences require early identification and intervention.

Monitor for reading and learning problems related to speech and language delays.

Hypernasality may develop at ages 10 to 14 due to normal shrinkage of adenoid tissue occurring at this time.

Assess the child’s self-perception and coping skills. Assess the family’s support systems and coping mechanisms.

Help school-age children deal with teasing (as a result of being “different” from their peers) by allowing them to express their feelings and guiding their response: ignoring the remark, responding with a joke or good-natured tease, or educating the teaser.

The school nurse can also help by performing frequent hearing evaluations, communicating with staff, and educating the school community on the child’s condition and individual needs.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseNelson, P., Glenny, A.-M., Kirk, S., et al. (2012), Parents’ experiences of caring for a child with a cleft lip and/or palate: A review of the literature. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(1), 6-20.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Instruct on continued protection of the mouth after surgery. Child cannot put anything in mouth, including lollipops.

Demonstrate how to rinse mouth after eating.

Advise parents on the introduction of solid foods; semiupright position or upright position; avoid spicy or acidic foods, which may irritate the oral and nasal cavities; avoid hard, sharp-edged foods, such as raw carrots or potato chips.

Advise on increased risk of ear infections and need to seek medical attention for colds, ear pain, fever, or other signs and symptoms. Frequent hearing screens and tympanometry should be done to monitor the effects of middle ear pathology. Note: Hearing should be monitored at least every 6 months during the first year of life and then annually to prevent hearing impairment.

Encourage modeling “good speech” by providing a stimulating language environment, and encourage spontaneous imitations of sounds at home.

Stress the importance of speech therapy and practicing exercises as directed by the speech therapist.

Encourage thorough brushing of teeth, regular dental examinations, and fluoride treatment as indicated due to risk of tooth decay related to defective enamel and abnormally positioned teeth with clefts.

Advise the parents on current therapies available: bone grafting providing permanent teeth support, dental implants to replace missing teeth, speech prosthesis for incomplete velopharyngeal closure.

Help the parents realize that, although rehabilitation is extensive, their child can live a normal life.

For additional information and support, refer patients and family to the Cleft Palate Foundation (www.cleftline.org) and Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome Educational Foundation (www.vcfsef.org).

Refer families to companies that manufacture bottles for cleft palate: Enfamil (Mead Johnson) Cleft Palate Nurser, 1-800-222-9123; Medela Haberman Feeder, 1-800-435-8316; Pigeon Bottle (Children’s Medical Ventures), 1-888-766-8443.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Infant feeds with appropriate feeding device in small amounts every 2 to 3 hours.

No signs of infection.

Parents involved with care; demonstrate contact with infant as seen by holding and talking to infant.

Proper positioning maintained, no signs of aspiration.

Parents demonstrate proper feeding technique as evidenced by adequate nutrition and weight gain.

Parents and child prepared for surgery.

Parents express understanding of postoperative home care procedures and identify supportive resources.

Esophageal Atresia with Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseAlberti, D., Boroni, G., Corasaniti, L., et al. (2011). Esophageal atresia: Pre and post operative management. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 24(Suppl. 1), 4-6.

Pinheiro, P., Simoes e Silva, A., & Pereira, R. (2012). Current knowledge on esophageal atresia. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 18(28), 3662-3672.

Esophageal atresia (EA) is failure of the esophagus to form a continuous passage from the pharynx to the stomach during embryonic development. EA can occur with tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), which is an abnormal connection between the trachea and esophagus. EA/TEF occurs in approximately 1 in 3,500 births.

Clinically, EA/TEF is divided equally into isolated EA and syndromic EA. Additional defects vary in severity, with cardiac anomalies as the most common (14.7% to 28%) and life-threatening. Currently, an overall survival of 85% to 90% has been reported from developed countries. In developing countries, however, several factors contribute to higher mortality rates. Such factors include prematurity, delay in diagnosis with an increased incidence of aspiration pneumonia, and a shortage of qualified nurses.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Cause is unknown in most cases and likely multifactorial. Possible influences include:

Low evidence for inheritable genetic factor

Six to 10% due to chromosomal (structural) abnormalities, including trisomies (12, 18, 21), and partial deletions such as 13q13-qter, 22q11.2.

Teratogenic stimuli, such as the anticancer drug adriamycin and diethylstilbestrol (DES).

Failure of proper separation of the embryonic channel into the esophagus and trachea occurring during the 4th and 5th weeks of gestation.

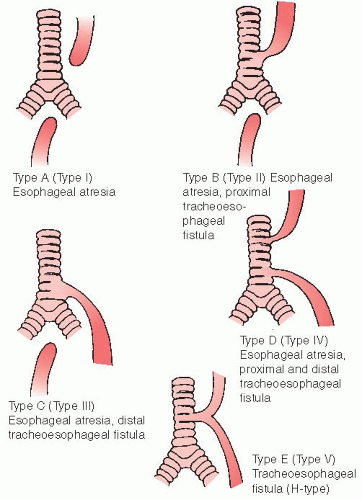

Esophageal atresia can be classified as (see Figure 48-2):

Type I (Type A): proximal and distal segments of esophagus are blind; there is no connection to trachea; accounts for approximately 7% of cases; second most common.

Type II (Type B): proximal segment of esophagus opens into trachea by a fistula; distal segment is blind; rare, 0.8% of cases.

Type III (Type C): proximal segment of esophagus has blind end; distal segment of esophagus connects into trachea by a fistula; most common, with 86% of cases. (Discussion is limited to this type.)

Type IV (Type D): esophageal atresia with fistula between proximal and distal ends of trachea and esophagus (rare, 0.7% of cases).

Type V (Type E): proximal and distal segments of esophagus open into trachea by a fistula; no esophageal atresia but sometimes referred to as an H-type fistula; occurs in 4.2% of cases; not usually diagnosed at birth.

Associations:

Down syndrome.

VACTERL syndrome (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac anomaly, TEF fistula with EA, renal defects, and radial limb dysplasia).

Feingold syndrome.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseGenevieve, D., de Pontual, L., Amiel, J., et al. (2011). Genetic factors in isolated and syndromic esophageal atresia. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 52(Suppl. 1), S6-S8.

Clinical Manifestations

These appear soon after birth.

Excessive secretions.

Constant drooling.

Large amount of secretions from nose.

Saliva or formula accumulates in upper esophageal pouch and is aspirated into airway.

Intermittent, unexplained cyanosis and laryngospasm.

Caused by aspiration of accumulated saliva in blind pouch.

Gastric acid is regurgitated through distal fistula.

Abdominal distention.

Occurs as a result of air entering the lower esophagus through the fistula and passing into the stomach, especially when the child is crying.

Violent response after first or second swallow of feeding.

Infant coughs and chokes.

Fluid returns through nose and mouth.

Cyanosis occurs.

Infant struggles.

Poor feeding.

Inability to pass catheter through nose or mouth into stomach; tip of catheter stops at blind pouch, or atresia. Note: Be aware of coiling of catheter; coiling may make catheter appear to be descending into stomach.

Infant can be premature and pregnancy complicated by polyhydramnios. Look for other birth anomalies.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Ultrasound scanning techniques enable TEF to be identified in utero for some infants.

Failure to pass a 10F catheter (smaller catheters may coil) into the stomach through nose or mouth. Catheter is left in situ while an x-ray confirms the diagnosis.

pH of tracheal secretions is acidic.

Flat-plate x-ray of abdomen and chest may reveal presence of gas in stomach and catheter coiled in the blind pouch. Barium x-ray may be used in some cases.

Electrocardiogram and echocardiogram are performed because there is a high association with cardiac anomalies.

Management

Immediate Treatment

Propping infant at 30-degree angle, supine or side-lying, to prevent reflux of gastric contents.

Nasogastric (NG) tube remains in the esophagus and is aspirated frequently to prevent aspiration until continuous low suction is applied.

Pouch is washed out with normal saline to prevent thick mucus from blocking the tube.

Gastrostomy to decompress stomach and prevent aspiration; later used for feedings.

Nothing by mouth (NPO); IV fluids.

Comorbidities, such as pneumonitis and heart failure, are treated.

Supportive therapy includes meeting nutritional requirements, IV fluids, antibiotics, respiratory support, and maintaining thermally neutral environment.

Surgery

Prompt primary repair: fistula found by bronchoscopy is divided, followed by esophageal anastomosis of proximal and distal segments if infant weight permits and is without pneumonia.

Short-term delay: subsequent primary repair is used to stabilize infant and prevent deterioration when the patient’s condition contraindicates immediate surgery.

Staging: initially, fistula division and gastrostomy are performed with later secondary esophageal anastomosis or colonic transposition performed approximately 1 year later to effect total repair. Approach may be used with a very small, premature infant or a very sick neonate or when severe congenital anomalies exist.

Circular esophagomyotomy may be performed on proximal pouch to gain length and allow for primary anastomosis at initial surgery.

Cervical esophagostomy: when ends of esophagus are too widely separated, esophageal replacement with segment of intestine (colonic transposition) is done at ages 18 to 24 months.

Fiberoptic tracheoscopy-assisted repair of tracheoesophageal fistula can expedite and facilitate surgery on ventilated patients.

Staged repair resulted in least amount of GI dysmotility postoperatively.

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseLacher, M., Froehlich, S., von Schweinitz, D., et al. (2009) Early and long term out come in children with esophageal atresia treated over the last 22 years. Surgery, 145(6), 675-681.

Complications

Note: Higher rates of complications occur in patients with cardiac anomalies and low birth weight.

Death from asphyxia.

Pneumonitis/pneumonia secondary to salivary aspiration and/or gastric acid reflux.

Leak at anastomosis site: most common and dangerous complication (15-20%).

Recurrent fistulas.

Esophageal strictures (30-40%).

Abnormal function of distal esophagus sphincter (gastroesophageal reflux can be found in approximately 50% of these infants).

Esophagitis.

Tracheomalacia (10-20% of these patients).

GERD (40-65%).

Feeding problems with older children due to esophageal dysmotility (95%).

Nursing Assessment

Assessment begins immediately after birth.

Be alert for risk factors of polyhydramnios and prematurity.

Suspect in infant with the following:

Excessive amount of mucus.

Difficulty with secretions.

Cyanotic episodes (unexplained).

Report suspicion to health care provider immediately.

Nursing Diagnoses

Preoperative

Risk for Aspiration related to structural abnormality.

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to inability to take oral fluids.

Anxiety of parents related to critical situation of neonate.

Postoperative

Ineffective Airway Clearance related to surgical intervention.

Ineffective Infant Feeding Pattern related to defect.

Acute Pain related to surgical procedure.

Impaired Tissue Integrity related to postoperative drainage.

Risk for Injury related to complex surgery.

Risk for Impaired Attachment related to prolonged hospitalization.

Nursing Interventions

Preventing Aspiration

Position the infant supine with head and chest elevated 20 to 30 degrees to prevent or decrease reflux of gastric juices into the tracheobronchial tree.

This position may also ease respiratory effort by dropping the distended intestines away from the diaphragm.

Side-lying position can be used if the risk of aspiration from being supine is greater than the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS); supine positioning is preferred to reduce the risk of SIDS.

Turn frequently to prevent atelectasis and pneumonia.

Perform intermittent nasopharyngeal suctioning or maintain indwelling Sump tube with constant suction to remove secretions from esophageal blind pouch.

Tip of tube is placed in the blind pouch.

Sump tube allows air to be drawn in through a second lumen and prevents tube obstruction by mucous membrane of pouch.

Maintain indwelling tube patency by irrigating with 1 mL normal saline solution frequently.

Place the infant in an Isolette or under a radiant warmer with high humidity to aid in liquefying secretions and thick mucus. Maintain the infant’s temperature in thermoneutral zone and ensure environmental isolation to prevent infection by using Isolette.

Administer oxygen, as needed.

Suction mouth to keep it clear of secretions and prevent aspiration. Provide mouth care.

Be alert for indications of respiratory distress.

Retractions.

Circumoral cyanosis.

Restlessness.

Nasal flaring.

Increased respiration and heart rate.

Maintain NPO status.

Administer antibiotics, as ordered, to prevent or treat associated pneumonitis.

Observe infant carefully for any change in condition; report changes immediately.

Check vital signs, color and amount of secretions, abdominal distention, and respiratory distress.

Evaluate for complications that can occur in any neonate or premature infant.

Be available and recognize need for emergency care or resuscitation.

Have resuscitation equipment on hand.

Accompany the infant to other departments and the operating room in Isolette with portable oxygen and suction equipment.

Monitor for signs or symptoms that may indicate additional congenital anomalies or complications.

Gastrostomy tube (GT) may be placed before definitive surgery to aid in gastric decompression, prevention of reflux, or nutrition.

Preventing Dehydration

Administer parenteral fluids and electrolytes as prescribed.

Monitor vital signs frequently for changes in blood pressure (BP) and pulse, which may indicate dehydration or fluid volume overload.

Record intake and output, including gastric drainage (if GT for decompression is present) and weight of diapers.

Reducing Parental Anxiety

Explain procedures and necessary events to parents as soon as possible.

Orient parents to hospital and intensive care nursery environment.

Allow family to hold and assist in caring for infant.

Offer reassurance and encouragement to family frequently. Provide for additional support by social worker, clergy, and counselor, as needed.

Maintaining Patent Airway

Keep endotracheal (ET) tube patent by frequent lavage and suction. Note: Reintubation could damage the anastomosis.

Suction frequently; every 5 to 10 minutes may be necessary, but at least every 1 to 2 hours.

Observe for signs of obstructed airway. Ventilatory support is continued until clinically stable (usually 24 to 48 hours).

Request that the surgeon mark a suction catheter, indicating how far the catheter can be safely inserted without disturbing the anastomosis (usually 2 to 3 cm).

Administer chest physiotherapy, as prescribed.

Change the infant’s position by turning; stimulate crying to promote full expansion of lungs.

Elevate head and shoulders 20 to 30 degrees.

Use mechanical vibrator 2 to 3 days postoperatively (to minimize trauma to anastomosis), followed by more vigorous physical therapy after the third day.

Continue use of Isolette or radiant warmer with humidity.

Be prepared for an emergency: have emergency equipment available, including suction machine, catheter, oxygen, laryngoscope, ET tubes in varying sizes.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTCare should be taken not to hyperextend the neck, causing stress to the opera tive site.

Providing Adequate Nutrition

Feedings may be given by mouth, by gastrostomy, or (rarely) by a feeding tube into the esophagus, depending on the type of operation performed and the infant’s condition.

The gastrostomy is generally attached to gravity drainage postoperatively, then elevated and left open to allow for air to escape and gastric secretions to pass into the duodenum before feedings are begun.

Practice patterns differ regarding when to start feedings but generally minimal enteral nutrition is beneficial in promoting gut motility, decreasing bacterial overgrowth, and decreasing the stress on the liver; these “trickle” feedings are given at a rate of 5 to 20 mL/kg per day.

Give the infant a pacifier to suck during feedings, unless contraindicated.

Use care to prevent air from entering the stomach, thereby causing gastric distention and possible reflux.

Continue gastrostomy feedings until the infant can tolerate full feedings orally.

Providing Comfort Measures

Position comfortably.

Avoid restraints when possible.

Administer mouth care frequently.

Offer pacifier frequently.

Assess for pain and administer analgesics, as ordered (see page 1446).

Caress and speak or sing to infant frequently. Handling should be kept to a gentle minimum.

Maintaining Chest Drainage

Assess type of chest drainage present (determined by surgical approach). Report saliva or hemorrhage.

Retropleural—small tube in posterior mediastinum; may be left open for drainage.

Transthoracic—chest tube placed in pleural space and connected to suction.

Keep tubing patent: free from clots, unkinked, and without tension.

If a break occurs in the closed drainage system, immediately clamp tubing close to the infant to prevent pneumothorax.

Observing for Complications

Inspect for leak at the anastomosis, causing mediastinitis, pneumothorax, and saliva in chest tube: hypothermia or hyperthermia, severe respiratory distress, cyanosis, restlessness, weak pulses.

Continue to monitor for complications during the recovery process.

Stricture at the anastomosis: difficulty in swallowing, vomiting, or spitting-up of ingested fluid; refusing to eat; fever secondary to aspiration and pneumonia.

Recurrent fistula: coughing, choking, and cyanosis associated with feeding; excessive salivation; difficulty in swallowing associated with abnormal distention; repeated episodes of pneumonitis; general poor physical condition (no weight gain).

Atelectasis or pneumonitis: aspiration, respiratory distress.

Provide meticulous care for cervical esophagostomy— artificial opening in the neck that allows for drainage of the upper esophagus.

Keep the area clean of saliva.

Wash with clear water.

Place an absorbent pad over the area.

As soon as possible, allow the infant to suck a few milliliters of milk at the same time gastrostomy feeding is being done. Advance the infant to solid foods, as appropriate, if esophagostomy is maintained for a few months.

Encourage sucking and swallowing.

Familiarize the infant with food so that when able to eat orally, infant will be used to it.

Begin oral feedings 10 to 14 days postoperatively after anastomosis, as directed.

Feed slowly to allow the infant time to swallow.

Use upright sitting position to avoid risk of regurgitation.

Burp frequently or vent GT.

Do not allow the infant to become overtired at feeding time. Note heart rate.

Try to make each feeding a pleasant experience for the infant. Use a consistent approach and patience. Encourage parental involvement.

Stimulating Parent-Infant Attachment

Gently hold and cuddle the infant for feedings and after feedings.

Encourage parents to cuddle and talk to the infant.

Provide for visual, auditory, and tactile stimulation, as appropriate, for the infant’s physical condition and age.

Provide opportunities for the parents to learn all aspects of care of their infant.

Encourage the parents to talk about their feelings, fears, and concerns.

Help to develop a healthy parent-child relationship through flexible visiting, frequent phone calls, and encouraging physical contact between child and parents.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseDelacourt, C., Hadchouel, A., Toelen, J., et al. (2012). Long term respiratory out comes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia, esophageal atresia and cardiovascular anomalies. Seminars in Fetal Neonatal Medicine, 17(2), 105-111.

Teach carefully and thoroughly all procedures to be done at home. Show the parents how to do them and then watch return demonstration of the following procedures:

Gastrostomy feedings and care.

Esophagostomy care with feeding technique.

Suctioning.

Identifying signs of respiratory distress.

Advise parents that esophageal motility will be affected for many years, due to the narrowed abnormal esophagus emptying slowly and tension on the stomach from the anastomosis.

Reflux may increase after surgery, thus should be maximally treated due to the risk of developing esophageal strictures.

Monitor weight gain and developmental progress.

Observe parental feeding technique.

Encourage parents to discuss child’s condition with daycare workers, teachers, school nurse, or other responsible adults in close contact with the child so that they will be able to recognize possible problems and reinforce good eating habits.

To compensate for altered motility, encourage cutting food into small pieces, chewing food well, swallowing food with fluid, and sitting upright while eating.

Observe parent-child interaction to assess for overprotection and appropriate coping skills.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Help the parents understand the psychological needs of the infant for sucking, warmth, comfort, stimulation, and affection. Suggest that activity be appropriate for age.

Encourage the parents to continue close medical follow-up and help them learn to recognize possible problems.

Eating problems may occur, especially when solids are introduced.

Repeated respiratory tract infection should be reported.

Occurrence of stricture at site of anastomosis weeks to months later may be recognized by difficulty in swallowing, spitting of ingested fluid, and fever. Continue all reflux medications until advised otherwise. Medications should be adjusted by weight as infant grows.

Dilatation of esophagus may be necessary to treat stricture at the site of the anastomosis.

Signs of fistula leakage are dusky color or choking with feeding.

Help the parents understand the need for good nutrition and the need to follow the diet regimen suggested by the health care provider.

Reassure parents that an infant’s raspy cough is normal and will gradually diminish as the infant’s trachea becomes stronger over 6 to 24 months (most infants have some tracheomalacia).

Teach parents to guard against the child swallowing foreign objects.

Help and support can be given by introducing the parents to other parents of children with TEF.

For additional information and support, refer parents to EA/TEF Family Support Connection (www.eatef.org), TEF Vater (www.tefvater.org), Birth Defect Research for Children (www.birthdefects.org), International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (www.aboutkidsgi.org), Boston Children’s Hospital (www.childrenshospital.org), or the March of Dimes Foundation (www.modimes.org).

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

No cyanosis or respiratory distress.

Hydrated; urine output adequate.

Parents hold and talk to infant; express concerns.

Postoperatively, tolerates gastrostomy feedings without distention or regurgitation.

Infant thrives, with adequate weight gain.

Infant sleeps and rests without irritability or pain.

Chest tube in place with minimal drainage.

Feeds without regurgitation 12 days postoperatively.

Parents caring for infant postoperatively and assisting with feedings.

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GER) and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseVandenplas, Y., Rudolph, D., Di Lorenzo, C., et al. (2009). Joint Recommenda tions of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 49(4), 498-547.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the passage of gastric contents into the esophagus. The barrier between the stomach and esophagus is controlled primarily by pressure at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). GER is a normal physiologic process and occurs in all healthy infants and children, usually several times a day, without symptoms or sequelae. Of all infants with GER, 50% will be symptomatic (vomiting) during the first 3 months of life; 67% of infants ages 4 to 9 months will have symptoms; and 5% of ages 10 to 12 months will have symptoms. Symptomatic GER often self-resolves by 12 to 14 months of age.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the symptom complex that results as a complication of GER. GERD is used to describe a condition when this reflux process causes bothersome symptoms and complications, such as significant discomfort and altered feeding and sleeping patterns. Clinical manifestations include vomiting, dysphagia, food refusal, poor weight gain, failure to thrive (FTT), esophagitis, irritability, abdominal pain, substernal pain, respiratory disorders, asthma, and apparent life-threatening events (ALTE) or apnea.

The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition has formulated guidelines for the diagnosis and management of GER and GERD in infants and children; however, these guidelines are not intended for the management of neonates less than 72 hours old, premature neonates, or infants/children with neurologic or anatomic abnormalities of the upper GI tract. The American Academy of Pediatrics has also endorsed these guidelines.

Supportive care by nurses and other health care staff regarding feeding techniques and nutrition is often sufficient for patients with GER. GERD may require additional interventions such as changes to feeding regimen or medication therapy.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

GER

The LES is a physiologic, rather than an anatomic, segment that forms an antireflux barrier.

Two to 5 cm in length.

Characterized by a pressure greater than that found proximally in the esophagus or distally in the stomach.

Constitutes an effective barrier to protect the esophageal mucosa and airway passages from damage by gastric contents (acid, pepsin, bile salts, food).

Neuromuscular connection is weak in infants, GER peaks at age 6 months and usually resolves by 12 months.

GERD

Episodes of GERD with aspiration of refluxed material are more likely to occur during the nocturnal period—when the esophagus and stomach are leveled and the swallowing response to reflux and airway protection mechanisms are blunted by sleep.

Cause is undetermined in most patients; however, possible causes include:

Delayed neuromuscular development.

Cerebral defects.

Obstruction at or just below the pylorus (eg, pyloric stenosis, malrotation).

Physiologic immaturity.

Increased abdominal pressure.

Obesity.

Cystic fibrosis.

Congenital esophageal disease.

Associated conditions that contribute to reflux include:

Chronic lung disease—there is a higher incidence of reflux in infants with this condition. It appears to be related to the duration of the episode and how proximal the reflux occurs, possibly contributing to poor clearance.

Trauma/mechanical causes that affect the LES.

Indwelling orogastric/NG enteric feeding tube.

Surgery on the esophagus or stomach.

Mechanical ventilation.

Extreme changes in position, lying completely flat, seating devices for infants greater than a 30% incline (increases intra-abdominal pressure).

Hiatal hernia.

Studies show a reduced incidence of reflux in the prone position versus the supine position; however, the American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Back to Sleep” program discourages prone positioning due to increased incidence of SIDS.

Protein allergy: increased inflammation in the mucosa of the esophagus and stomach, altering motility.

Medications/drugs that affect LES and increase gastric acidity, such as bronchodilators, antihypertensives, diazepam, meperidine, morphine, prostaglandins, calcium channel blockers, nitrate heart medications, anticholinergics, adrenergic drugs, caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine.

Cystic fibrosis, cardiac disease, and other chronic illnesses.

Clinical Manifestations of GERD

Infants

Vomiting or regurgitation of formula or breast milk.

Irritability, excessive crying with or without association with vomiting.

Sleep disturbances.

Arching, stiffening.

It is recommended that the infant be referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist if the following manifestations occur:

Refusal to eat.

Weight loss or failure to gain weight.

Dehydration.

Recurrent respiratory symptoms, such as cough, wheezing, stridor, pneumonia, otitis media, bronchitis.

ALTE: blue spell, decreased responsiveness, limp, apnea, bradycardia. (Note: The exact relationship between GER and ALTE is not clear despite continued investigation. Indeed, both apnea and reflux are common in premature neonates.)

Eructation (belching).

Sandifer’s syndrome (rare)—dystonic posturing caused by reflux.

Anemia (from chronic esophagitis).

Hematemesis (vomitus with blood).

Occult blood in stool.

Hypoproteinemia: low albumin due to severe inflammation and protein losses in the GI tract; can be seen with or without malnutrition and FTT.

Older Children

Intermittent vomiting.

Chronic heartburn or regurgitation.

Upper abdominal discomfort; pressure or “squeezing” feeling.

Chronic respiratory/airway symptoms, such as cough, stridor, otitis media, bronchitis, asthma.

Food refusal.

Dysphagia: difficulty swallowing.

Odynophagia: painful swallowing.

Anemia (from chronic esophagitis).

Hematemesis.

Hypoproteinemia.

Occult blood in stool.

Diagnostic Evaluation

History of infant’s or child’s feeding habits.

Multiple intraluminal impedance and esophageal pH monitoring can be performed on all ages; no sedation necessary.

Considered gold standard for reflux and is performed over 24 hours, but does not indicate whether aspiration is occurring.

Used as an index of esophageal acid exposure; however, esophageal impedance studies have been found to be more accurate, especially in the neurologically impaired child.

The child must be off acid-suppressing medications for 48 to 72 hours so that acid pH can be detected.

Gastric motility medications may or may not be held depending on the reason for performing the study.

Most centers allow the patient to go home and return 24 hours later. Exceptions include the fragile child, premature infant, infant with active respiratory symptoms, or the child with significant symptoms who requires close observation because reflux may exacerbate while off reflux medications.

Not indicated in the infant/child who is vomiting, unable to tolerate bolus feedings, or acutely ill. Because the probe is inserted in a nares, infant/children with oxygen requirements may not tolerate the study.

Endoscopy and biopsy allow for visualization of esophageal, gastric, and duodenal mucosa.

Indicated for severe GERD or failure of medical management.

Biopsy can determine cause: allergy (eosinophilic), inflammation, chemical injury, or Barrett’s esophagus.

Mechanical problems such as strictures, webs, and duplication/cysts will be visualized.

For this procedure, sedation and anesthesia are necessary.

Reflux medications do not have to be discontinued for the study.

Can be done on the child who is not tolerating feedings. However, severity of illness may prevent study from being performed due to risk associated with procedure, such as with anesthesia, infection, bleeding, cardiac.

Technetium scintigraphy (milk/emptying scan) to assess gastric emptying and associated aspiration. This is not a reliable test for determining GERD.

Sedation is not necessary and the study can be performed on children of all ages.

Involves drinking/eating food with radionuclide, followed by dynamic sequenced imaging.

Not indicated in the infant/child who is vomiting, unable to tolerate bolus feedings, or acutely ill.

Acid suppression medications do not interfere with the study.

Modified barium swallow—also called videofluoroscopy.

Assesses oral pharyngeal function and potential for aspiration from oral intake using several consistencies of feedings. This is not a reliable test for determining GERD.

Sedation is not necessary for this procedure, but does require cooperation with eating.

Should not be performed on the infant/child with acute respiratory symptoms or one identified by speech therapy or occupational therapy as being at risk for aspiration.

Reflux medications do not have to be discontinued for the study.

Speech therapist can be present for the exam to offer detailed assessment of oral-motor skills and swallowing.

Esophageal manometry to measure pressure inside the LES.

It is a cooperative, nonsedated procedure and can only be used on an older child.

Reflux medications generally do not have to be discontinued for the study.

Intraluminal esophageal impedance to detect the flow of liquids and gas through the esophagus may be used in combination with manometry.

Polysomnography may be used for evaluation of infant apnea and sleep apnea.

Complications

Complications result from frequent and sustained reflux of gastric contents into lower esophagus.

Recurrent pulmonary disease.

Chronic esophagitis.

FTT.

Anemia.

ALTE, although evidence is not strong.

Esophageal stricture from scarring.

Barrett’s esophagus: the replacement of distal esophageal mucosa with a potentially malignant metaplastic epithelium caused by chronic exposure to acid.

Chronic sinusitis/otitis media.

There is an unclear relationship between GERD and dental erosion/caries.

Management

Goal of treatment is to alleviate and relieve symptoms and prevent complications. May be treated medically through careful positioning, feeding techniques, and medication or surgically.

Positioning for GER

Esophageal monitoring has demonstrated that infants have significantly fewer episodes of GER when prone. Several studies support less incidence of reflux episodes in the prone and left-side sleeping position; however, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, along with the American Academy of Pediatrics, endorses the following recommendations:

Place infant up over shoulder after feedings, avoid sitting on lap to burp, which increases intra-abdominal pressure.

Handle the infant gently, with minimal movement during and after feeding.

Feeding for GER

Two- to 4-week trial of hypoallergenic formula in the formula-fed infant. Continuance of breastfeeding with the mother eliminating milk and soy products is encouraged, as allergen sensitivity can contribute to GER. No studies support the need for dietary restriction in mothers who breastfeed, but in anecdotal reports, infants appear to improve when dairy products are reduced. Trial of partially hydrolyzed formula and/or hydrolyzed formula is useful for refractory symptoms or for those infants/children with signs of allergy, anemia, constipation, occult positive stools, vomiting.

Thickened feedings with dry rice cereal (1 tbsp per ounce of formula) or commercial thickening agent may be used. Thickening does not decrease episodes of reflux but does decrease episodes of vomiting. Commercial formulas thickened with rice starch are now available, but no studies regarding their efficacy have been published; they require an acidic environment to work and, therefore, necessitate the discontinuation of acid suppression medications. Thickening of breast milk may be necessary in infants with poor weight gain.

Pectin liquid partially decreases GER, as measured by esophageal pH monitoring, and might improve vomiting and respiratory symptoms in children with cerebral palsy.

Small, frequent feedings followed by upright positioning with infant held over the shoulder.

Concentrating formula is a method of increasing calories for the volume-sensitive infant.

Avoid constant feeding (grazing), which reduces appetite and, ultimately, caloric intake.

Comfort the infant to reduce crying before and after meals, which increases intra-abdominal pressure and swallowing of air, increasing the likelihood of reflux.

Use a pacifier for nonnutritive sucking after eating to avoid overeating.

Feeding for GERD

Transgastric (transpyloric) enteric feeding tube used for infants when reflux medical management fails and symptoms persist; can reduce number of reflux episodes, but has not been shown to significantly reduce episodes of apnea.

There are concerns regarding using these feeding tubes in neonates; however, the rate of complications does not appear to be statistically significant in recent reports.

The procedure should be performed by a skilled pediatric radiologist or neonatal intensive care nurse, using a smallcaliber soft polyurethane nonweighted feeding tube.

Considered a temporary feeding method (to help infant/child gain weight and improve respiratory symptoms) until further options can be explored, such as surgery— Nissen fundoplication or jejunostomy.

To prevent clogging, tubes should be flushed at least four to six times per day and before and after medication administration. If the tube clogs or dislodges, the family must return to a qualified center for reinsertion.

If feeding difficulty persists, consult dietitian and speech and/or occupational therapist.

Older child:

Nothing to eat 2 hours before bedtime.

Avoid spicy and acidic foods (onions, citrus products, apple juice, tomatoes), esophageal irritants (chocolate, caffeinated beverages, peppermint, and secondhand smoke), and carbonated beverages.

Chew gum (stimulates parotid secretions, which augment esophageal clearance and provide a buffering effect).

Other Lifestyle Changes for GERD

Prevent obesity.

Avoid tight or constrictive clothing.

Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, especially at bedtime.

Drug Therapy for GERD

Often used in combination with lifestyle changes. Prescribed for a 12-week trial and can be tapered and discontinued if symptoms resolve.

Antacids—buffer existing acids and also increase serum gastrin levels, leading to increase in LES pressure (symptomatic relief). Chronic antacid therapy is generally not recommended unless ordered by a gastroenterologist.

Histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonists—act by reducing hydrochloric acid and pepsinogen secretion by blocking histamine receptors on the parietal cells.

Cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine.

Oral dosing of t.i.d. versus b.i.d. has demonstrated improved duration of acid suppression in study of infants (44% vs. 90%).

Tolerance to IV dosing within 6 weeks of usage has been observed.

PPIs—block all gastric acid secretion by binding and deactivating the H+/K+ ATPase enzyme pumps. To be activated, PPIs require acid in the parietal cell canalicus; therefore, they are most effective when the parietal cells are stimulated by a meal following a fast.

Omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, rabeprazole.

Generally given 15 to 30 minutes before a meal, one to two times per day.

Generally not recommended in combination with H2-antagonists due to interference with absorption (H2 reduces the acid necessary for PPI to work).

Reserved for infants and children resistant to H2-antagonist therapy. Gastroenterology specialist should be involved. Data on the pharmacology in infants and children are limited.

Dominant regurgitation in neonates and infants responds poorly to PPIs.

Prokinetic agents—the rationale for prokinetic therapy is based on the evidence that it enhances esophageal peristalsis and accelerates gastric emptying.

Metoclopramide most commonly used—an antidopaminergic agent whose efficacy is not well observed in clinical trials. Adverse effects include parkinsonian reactions, tardive dyskinesia, irritability, sleeplessness, and lowered seizure threshold.

Erythromycin at low dose: motility receptor agonist. Can be associated with dysrhythmia and increased incidence of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Contraindicated in some patients with preexisting cardiac conditions.

A surface agent sucralfate may be used—an aluminum complex that acts by adhering to mucosal lesions, reducing symptoms, and promoting healing.

May be used as an adjunct to an H2 blocker or PPI, and usually for a period of several weeks or less.

If used for esophagitis, should be made into a liquid preparation.

If used for ulcer or gastritis, it is inhibited by H2 blockers and PPIs due to the need for an acidic environment.

DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERTAll acid-altering medications may affect the efficacy of pH-dependent medications. Additionally, PPIs are metabolized to varying degrees by the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymatic system and may alter drug metabolism by induction or inhibition of the cytochrome P enzymes.

DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERTThe potential adverse effects of aluminum in infants and children should be considered before administering sucralfate; data on its efficacy and safety in children are inadequate.

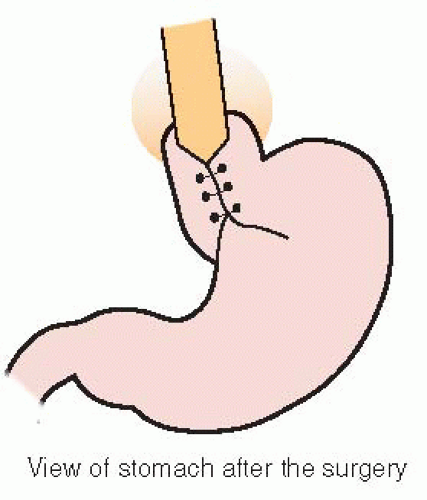

Surgical Management for GERD

Nissen fundoplication is the most commonly used surgical method to treat moderate to severe GERD that is unresponsive to medication therapy. Decisions concerning appropriate long-term feeding access must be individualized.

Involves wrapping of the fundus around the LES (see Figure 48-3).

Overall complication rate ranges from 2.2% to 45%.

Other surgical approaches include ventral (Thal) or dorsal (Toupet) semifundoplication.

In some studies, recurrence of reflux in the neurodisabled child is as high as 46%.

Simultaneous gastrostomy is usually performed for feeding purposes or as a temporary measure to decompress the stomach.

The most commonly reported complications of surgery include breakdown of the wrap, small bowel obstruction, gas bloat syndrome, infection, perforation, leaking at the anastomosis site, persistent esophageal stricture, esophageal obstruction, dumping syndrome, incisional hernia, and gastroparesis.

Reoperation rates range from 3% to 18%.

The greater the complexity of the infant or child’s health status, the greater the chance of complications.

Jejunostomy feeding tubes can be placed but are usually restricted to severe cases of recurrent GERD and/or failed Nissen procedure.

Most surgeons use either a standard GT or a low-profile tube (button).

Complications include intestinal obstruction and leaking.

Other Treatments Under Investigation

Investigation is underway to identify pathways and mechanisms that interfere or control the transient relaxation of the LES. Future understanding of this mechanism will aid in the development of lifestyle changes and medical management, which will assist in inhibiting transient relaxations. Reduction of gastric mechanoreceptor signaling to the brain has emerged as one of the likely sites of action for new reflux inhibitor drugs. The most promising among these appear to be the GABAB receptor agonists and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5).

Nursing Assessment

Obtain history of infant’s or child’s eating habits, including formula history, food allergies, volume tolerated at each meal.

Obtain history of complications from GER (ie, recurrent respiratory infections, asthma, poor weight gain).

Observe infant’s or child’s feeding behaviors. (Does child eat with a bottle, spoon, fingers? Can child feed self?)

Assess general appearance, skin integrity, and growth and development.

Nursing Diagnoses

Risk for Aspiration related to reflux of gastric contents.

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to decreased oral intake.

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to frequent vomiting.

Fear of eating related to distress.

Nursing Interventions

Preventing Aspiration

Administer medications via IV line until tolerating enteral feedings.

Administer prokinetics (motility agents) and acid suppressants 30 minutes before meals when bolus feeding schedule is instituted. Monitor for adverse effects.

Unless abnormal gastric dysmotility prior to surgery, most prokinetics are discontinued after Nissen fundoplication.

Maintain positioning, as stated above.

Use cardiac and apnea monitors for infants and children with severe reflux.

Observe for apneic periods of more than 20 seconds or accompanied by cyanosis, pallor, or bradycardia.

Document apnea episodes, associated symptoms, and recovery efforts.

Provide chest physiotherapy before rather than after meals, if ordered.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTAvoid slouching position because this may change angle of esophagus in relation to stomach, increase intra-abdominal pressure, and facilitate reflux of stomach contents.

Maintaining Adequate Nutrition

See also section on feeding, page 1604.

Provide concentrated formula if volume cannot be tolerated.

Seek nutrition consult if patient continues to have difficulty feeding.

Monitor for fatigue during feeding; increased effort to suck requires higher energy expenditures. If noted, referral to occupational/speech therapy and possible modified barium swallow study are advised.

Monitor weight on the same scale.

Accurately record activity of infant.

Amount of feeding taken; whether retained.

Any change in behavior as a result of feeding technique.

Explain to the breastfeeding mother that feeding modifications may need to be made, especially in infants with poor weight gain. Assist her to express milk, quantitate volume, thicken with cereal, and fortify breast milk with formula, as needed.

Follow postoperative instructions on initiation of feedings.

If the child has a GT:

Usually elevated and vented until return of bowel function.

Monitor drainage, avoid kinking, and follow orders for positioning for straight drainage, elevation, or clamping.

Maintaining Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

Monitor vital signs and assess skin turgor for signs of dehydration.

Observe and record accurately urine output.

Weigh diapers.

Measure amount, frequency, color, and concentration of voided urine.

Check specific gravity, if possible.

Monitor IV therapy, if ordered.

Monitor serum electrolytes, magnesium, phosphorus, and calcium. Replace, as ordered. Particular close monitoring is warranted if infant/child has draining gastrostomy.

Promote good skin care to prevent lesions of dry and delicate tissues.

Change position frequently.

Change soiled diapers promptly.

Apply lotion and gently massage any reddened areas.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTIf patient is malnourished, moni tor for refeeding syndrome until laboratory studies are stable. Refeeding syndrome can cause intracellular shifting of electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus, resulting in death. Laboratory studies should be monitored daily or more frequently if abnormal.

Reducing Fear of Eating

Provide thickened feedings to increase satisfaction for the infant.

Identify and attempt to reduce stress, especially around mealtime.

Feed the child in a quiet, calm environment.

Children like routines; feed at routine intervals by the person with whom the child is familiar and comfortable.

For the older child, encourage participation in family dinnertime so the child observes eating as a pleasurable experience.

Advise parents that clinical specialists in feeding disorders are available.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Recognize that home health care referral is appropriate for the following situations:

FTT: medication teaching and monitoring, teaching of formula preparation, positioning, weight.

Respiratory complications/ALTE: medication teaching and monitoring, assessment of respiratory status, teaching of monitor/cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), use of nebulizer.

Nissen fundoplication (with GT): medication teaching and monitoring; wound assessment; monitoring of bloating; dumping syndrome; formula intolerance; GT teaching, including pump teaching, venting, medication administration, tube changing.

Recommend careful feeding and behavioral diary to monitor symptoms and improvements.

Recognize that school and community activities may affect compliance for older children; work with the family to devise individualized management strategies.

Assist parents to discuss medication and lunchtime behaviors with teacher and school nurse so consistency can be maintained.

Assess need for community services, such as respite care, especially for single parent.

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Plan a program of intensive parental teaching on how to handle and care for the infant. Explain rationale to parents. Make sure that they have proper equipment for propping the infant. Help the parents understand that it is not necessary to keep infant in infant seat or propped up at all times.

Bathe or play with the infant before feeding.

Change position about 1 hour after feeding.

During the night after feeding, the infant can sleep in a semi-reclining (30 degrees) position.

Expect occasional small amounts of vomiting.

Offer clear, concise instructions. Focus on parental fears. Discuss techniques to promote development of infants while facilitating bonding and normal parental behavior.

If infant or child is not demonstrating complication of GER (ie, GERD), assist parents in understanding that GER is self-limited; symptoms usually disappear within 12 months.

If complications exist (GERD), referral to pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition specialists is recommended.

If Nissen fundoplication has been performed:

Teach gastrostomy care, if applicable (see page 1463). Make sure that the parents know how to use, clear, vent, assess, and replace the tube. Help them to understand the purpose of GT placement (feedings, venting, medications) and the need for surgical or gastroenterology follow-up care.

Explain about potential complications and when to call the health care provider. Such complications include gagging, retching, bloating, abdominal distention, fever, vomiting, diaphoresis, lethargy, diarrhea, weight loss. Generally, the family should contact the surgeon within the first 6 weeks postoperatively, whereas eventual follow-up is with the gastroenterologist.

It usually takes 12 weeks to heal; if the GT becomes dislodged in this period, the patient should be taken to the emergency department immediately.

Complications of a dislodged GT in the early postoperative period include peritonitis and bacteremia.

Help the parents understand the importance of follow-up for assessment of weight gain and development.

Assist with community resource planning (eg, education, advocacy, and financial assistance). Identify support groups.

Instruct parents and caregivers in CPR training before discharge of infant, if indicated.

Provide written and verbal instructions for medications and adverse effects.

Advise parents on when to call their health care provider in regard to their child’s symptoms. Danger signs of dehydration include a decrease in wet diapers, listlessness, lethargy, reduced appetite, sunken fontanelle; those for aspiration include respiratory distress and cyanotic spells, fever.

Encourage family to contact their health care provider immediately with treatment concerns or problems.

For additional information and support, contact the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (www.naspghan.org), the United Ostomy Association (www.uao.org), or the Pediatric/Adolescent Gastroesophageal Reflux Association (www.reflux.org).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access