Patients with renal disease

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the term used to describe a degree of chronic renal failure that, without dialysis or kidney transplantation, would end the patient’s life. Many such patients have complex and special needs. Many are elderly. (See Facts about end-stage renal disease.) All ESRD patients need palliative care, careful efforts to maintain quality of life and, eventually, end-of-life care.

Currently, there’s no cure for ESRD. The patient’s options include only hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, kidney transplantation, or death. Clearly, ESRD patients and their families face many decisions about life-prolonging versus palliative therapies. Ideally, palliative care increases as curative care decreases, and it encompasses all aspects of illness through death and bereavement. (See Models of end-of-life care.)

Facts about end-stage renal disease

Almost half of people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are older than age 65.

More than 72,000 dialysis patients die each year.

About 1 in 4 patients who die of ESRD do so because they withdrew from treatment.

Most patients with ESRD also have other diseases that contribute to their deaths.

Almost two-thirds of patients with ESRD die as hospital inpatients.

Few patients with ESRD die in hospice care.

Models of end-of-life care

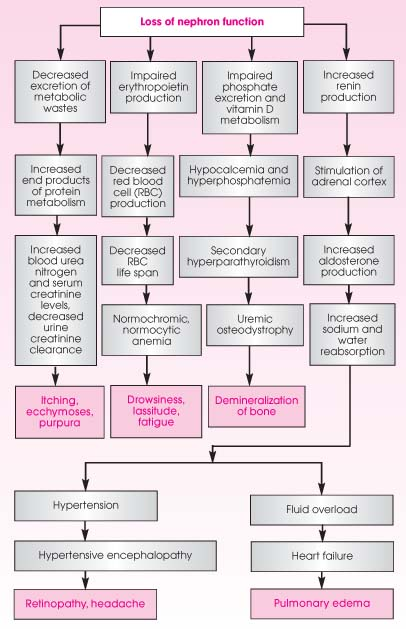

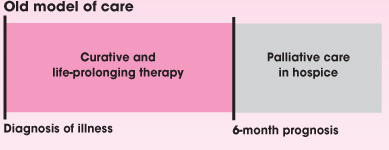

Many clinicians and patients have regarded hospice care as a distinct phase of treatment begun only when all other treatment has failed, as shown below. The emphasis was on a cure. Quality of life gained importance only when the hospice team arrived.

Old model of care

|

The new model of care begins at diagnosis and covers quality-of-life issues as they occur throughout the illness. If a cure isn’t possible, palliative care naturally progresses until hospice begins. As shown below, the 6-month prognosis then becomes just an administrative designation instead of a traumatic break with previous health care providers.

When caring for a patient with ESRD, as with other terminal illnesses, you’ll need to address both physical and psychosocial issues for both patient and family. You’ll play an essential role in assessing and managing the patient’s symptoms, including pain. And you may have to help with such difficult decisions as when to stop dialysis.

Assessment

Normally, the kidneys serve many functions, including:

regulation of osmotic pressure through absorption or excretion of sodium chloride and water

regulation of fluid volume using antidiuretic hormone and water

regulation of electrolytes, such as sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium

regulation of pH through hydrogen ion excretion and sodium bicarbonate absorption

excretion of wastes, such as urea, creatinine, uric acid, and ammonia

secretion of hormones, such as erythropoietin and renin.

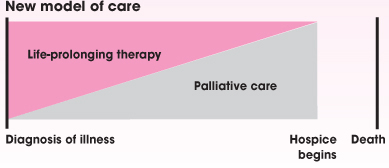

Damage to the kidney’s functional unit—the nephron—can render it nonfunctional and reduce the kidneys’ ability to carry out its normal duties. The glomerulus, a tuft of capillaries in the nephron, filters all blood entering the kidney. The glomerular filtration rate in a healthy adult averages about 120 ml/minute. If that figure falls to less than about 20%of normal, a series of events begins and may lead to chronic renal failure. (See Course of chronic renal failure.)

Symptoms of uremia most always occur if glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is less than 10%of normal. In fact, there’s a direct relationship between a decreased GFR and metabolic changes that result from the kidneys’ inability to regulate electrolytes, fluid, and acid-base balance and to excrete metabolic wastes and secrete hormones.

Several diagnostic measures are used to assess the presence of ESRD. These include a family history, blood tests, urine examination, kidney biopsy, and X-rays. The most common laboratory tests include:

blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level

serum creatinine level

BUN-to-creatinine ratio

creatinine clearance

biochemical profile, including the electrolytes sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and calcium

complete blood count

urinalysis

As ESRD progresses, BUN and serum creatinine levels increase, urine creatinine clearance decreases, serum potassium level increases, phosphorus level increases, calcium level decreases, and hemoglobin level and hematocrit decrease. Lack of dialysis would result in these values remaining abnormal and would lead to death.

Effects of end-stage renal disease

Renal system

Oliguria results from a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

Hyperkalemia results from decreased GFR and metabolic acidosis.

Metabolic acidosis results from the kidney’s inability to excrete hydrogen ions and reabsorb sodium and bicarbonate.

Hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia develop because the kidney can’t excrete phosphorus.

Hypotension and dehydration may occur during or after dialysis and may lead to further kidney ischemia.

Cardiovascular system

Hypertension results or worsens from fluid overload, stimulation of the renin-angiotensin mechanism, or the absence of prostaglandins.

Left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, or both may result from volume overload.

Arrhythmias may result from hyperkalemia, hypermagnesemia, acidosis, and decreased coronary perfusion.

Respiratory system

Pulmonary edema results from heart failure and fluid overload.

Pleuritis may result from toxic byproducts of metabolism.

Gastrointestinal system

Anorexia, hiccups, nausea, and vomiting occur with uremia.

GI bleeding may result from coagulation abnormalities and uremic gastric irritation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access