Patients with cancer

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States and the most common diagnosis in palliative and hospice care. The latter fact probably stems from several characteristics particular to cancer. For one thing, it’s possible to predict the course of most forms of cancer relatively accurately, which gives physicians some confidence in making referrals to end-of-life care. For another, end-stage cancer typically causes symptoms that can be relieved.

Lung, breast, prostate, and colon cancers cause most cancer deaths. Prostate cancer, the main hormone-related cancer in men, claims 30,000 lives yearly. Breast cancer kills 40,000 women yearly. Colon cancer kills 64,000 men and women yearly. And lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer deaths among Americans, kills 163,000 people yearly.

Often, it’s metastasis that causes the patient’s death, not the primary disease. Breast and prostate cancers typically metastasize to the brain, bone, lung, and liver. Advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (the most common lung cancer in hospice) typically spreads to structures around the lungs, such as the chest wall, heart, blood vessels, trachea, and esophagus. Colon cancer metastasizes to the lungs and liver.

The symptoms of end-stage cancer correspond to its spread. If a breast cancer patient has lung metastasis, for example, she’ll most likely have dyspnea. If cancer has spread to the liver, she probably will have anorexia. If the cancer is in the bone, she may have a pathologic fracture. Any of these metastases may cause pain.

Despite the common belief that cancer deaths are excruciatingly painful, virtually all pain in dying cancer patients can be relieved. In fact, virtually all end-stage cancer symptoms can be effectively reduced and managed. What’s more, patients dying of cancer typically have time to make apologies,

ask forgiveness, give forgiveness, and say “I love you” and “Good-bye.” By managing the symptoms common to end-stage cancer — such as pain, dyspnea, dehydration and anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, sleep problems, and emergencies — you can help make the patient’s final days among his most meaningful.

ask forgiveness, give forgiveness, and say “I love you” and “Good-bye.” By managing the symptoms common to end-stage cancer — such as pain, dyspnea, dehydration and anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, sleep problems, and emergencies — you can help make the patient’s final days among his most meaningful.

Pain

Nearly everyone who’s diagnosed with cancer expects to have pain — particularly if the cancer can’t be cured. Many patients believe the closer they get to death the more unbearable their pain will be. It’s true that cancer, especially end-stage cancer, can be painful. As tumors grow, they press on nearby tissues or infiltrate other organs. However, it’s also true that cancer pain can be relieved in nearly all dying patients. Here’s what you need to know about pain and ways to relieve it for patients at the end of life.

Types of cancer pain

A growing tumor causes a series of exchanges between peripheral nerves, spinal cord, and brain. Nociceptors, nerve cells that sense the presence of harm, transmit signals from the nerves to the spinal cord. There they interact with specialized nerve cells that act as gatekeepers, filtering the pain messages on their way to the brain. In severe pain, the “gates” are wide open and the message travels quickly to the brain, while milder pain travels at a slower speed.

Once the pain message reaches the brain, it’s interpreted as a physical sensation with complex links to both emotions and thought processes. Individual differences in the number of nociceptors, spinal cord gates, or cells in the nervous systems can cause differences in how much pain a patient experiences. So does culture. Culture not only determines how patients react to pain (crying loudly versus quiet stoicism); it also plays a role in determining how patients perceive pain.

The location and type of pain in end-stage cancer patients play a role in its sensation as well.

Somatic pain

Somatic pain occurs in skeletal tissue, muscles, and the surface of the skin. Patients usually describe somatic pain as dull or aching but localized; pain from bone metastases is somatic. Somatic pain responds well to most analgesics.

Visceral pain

Visceral pain results from infiltration, compression, extension, or stretching of the chest, abdominal, or pelvic viscera. Pain from pancreatic cancer is visceral. Patients usually describe visceral pain as pressure, as deep pain, or as squeezing pain. Visceral pain usually is diffuse and not well localized.

Neuropathic pain

This type of pain develops when a tumor presses on nerves or the spinal cord or when cancer spreads inside the spinal cord. Patients with neuropathic pain say it feels like burning or tingling. It may be localized to a specific spot, or it may be diffuse, affecting large or patchy areas.

Wind-up pain

When nerves transmit pain impulses to the brain for long periods of time, they become more effective at sending pain signals, and the brain becomes more effective at recognizing them. This heightened signaling causes wind-up pain, a type of pain that continues to intensify, becoming more difficult to treat the longer it continues.

Assessment

You can’t know how much pain a patient is having unless you ask. Then you have to believe the answer. This simple concept ensures that patients with end-stage cancer receive exemplary pain relief.

Instead of relying on facial grimacing, blood pressure readings, or sleep status, just ask the patient how much he hurts. Instead of assuming that patients tend to overestimate or underestimate their pain, simply accept that the true gauge of patient pain is the patient.

Tools

The most effective way to gauge your patient’s pain and how it changes over time is to use a pain rating scale. (See Pain assessment tools.) Choose the most appropriate of the many such scales that are available, including these:

a numbered scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain possible)

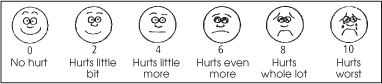

a series of faces with increasing emotions, a happy face indicating no pain and increasingly distressed faces for increasing pain

a visual analog scale, which uses a straight line, with the far left side meaning no pain and the far right side meaning the worst pain imaginable

a categorical scale, with four categories to describe pain (none [0], mild [1–3], moderate [4–8], severe [7–10])

a word scale using verbal descriptions of pain (horrible, burning, excruciating, agonizing, aching, and so on)

colors on a spectrum, starting on the left with an icy white-blue and ending with a deep red on the right. This scale is more prone to misinterpretation than the others because some patients may perceive icy-blue as a more painful color than deep red.

Pain assessment tools

Numeric pain rating scale

A numeric rating scale can help the patient quantify his pain. Have him choose a number from 0 (indicating no pain) to 10 (indicating the worst pain imaginable) to reflect his current pain level. He can either circle the number on the scale itself or verbally state the number that best describes his pain.

|

Visual analog scale

To use the visual analog scale, ask the patient to place a mark on the scale to indicate his current level of pain.

|

Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale

A child or an adult with language difficulties may not be able to describe in words or numbers the pain he’s feeling. If so, try a pain rating scale that uses facial expressions to gauge his pain level. Ask the patient to choose the face that best represents the severity of his pain. Explain the faces using a 0-to-10 scale and the descriptions included on the tool.

|

From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML: Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, ed. 7, St. Louis, 2005, p.1259. Used with permission. Copyright, Mosby.

Questions

Also, ask your patient to describe the details of his pain using such questions as these:

Describing the pain

If a patient has trouble pinpointing the character of his pain in his own words, you can help by providing descriptive words he can choose from. Offer the choices in small, related groups, such as, “Is your pain aching, burning, or stabbing?” Here are some descriptive words to get you started.

Aching

Burning

Constant

Crushing

Dull

Electric

Gnawing

Heavy

Intermittent

Pins and needles

Pressing

Prickling

Pulsing

Searing

Sharp

Shooting

Spasm

Stabbing

Throbbing

Can you describe your pain? (See Describing the pain.)

Where does it hurt?

Does it always hurt? Are there times your pain is better? Worse?

What else can you tell me about your pain?

What do you want your pain medication to do?

As your patient nears death, he’ll sleep more and wake less; eventually, he’ll become unresponsive. Most patients at the end of life can no longer tell you how much or what kind of pain they’re having. What’s more, nonverbal cues — such as changes in vital signs, moaning, grimacing, and sleep status — aren’t reliable indicators of pain in a dying patient. Don’t be fooled into thinking that a patient has no pain just because he can’t describe it. Keep giving the same analgesics, at the same dosage and on the same schedule that the patient was receiving them before he became nonverbal. Keep giving them until the patient dies. If needed, change from the oral to the rectal route; many analgesics, including morphine, controlled-release opioids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are absorbed well from the rectum.

Management

The number one goal in caring for dying patients with pain is to remove the obstacles to relieving your patient’s pain, including the errant beliefs of health care providers, patients, families, and administrators. (See Sources of ineffective pain management.)

Sources of ineffective pain management

Despite compelling, long-standing evidence for the importance of aggressive pain management, too many patients are living and dying with too much pain. Here are some reasons why pain management tends to be ineffective.

| Sources | Reasons |

|---|---|

| Physicians and nurses |

|

| Patients and families |

|

| Health care systems and facilities |

|

Principles of pain management

Many people fear pain management almost as much as they fear pain itself; to help provide your dying patient with the pain relief he needs and deserves, keep these points in mind.

Pain is whatever the patient says it is.

Pain can be relieved in virtually all patients at the end of life.

Treatment of a dying patient’s pain shouldn’t be withheld while the cause is determined.

Assess and reassess the patient’s pain continually.

Use standardized pain assessment tools.

If the gut works, use it. The oral route is the preferred route.

For most patients receiving end-of-life care, analgesics should be given on a schedule around the clock, not “as necessary.”

Make sure the patient has analgesic doses available for breakthrough pain — in the same drug he’s receiving for around-the-clock pain control.

There’s no “ceiling” dose of opioids in a patient with end-stage cancer.

Anticipate adverse effects, and treat them before they arise.

Use adjunct drugs as needed according to the patient’s symptoms

Include meditation, music, and other nondrug interventions in the plan of care to relieve pain. (See Nondrug interventions for pain.)

Provide ongoing instruction in pain management to the patient and family.

Escalating intractable pain is a medical emergency that requires prompt attention. Stay in contact with the patient’s physician until the pain is relieved. The patient may need surgery, radiation, or sedation. If the patient is at home, a short-term inpatient stay for pain management may be warranted.

Steps of pain management

Whether a patient with end-stage cancer has moderate or severe pain, the best course is to maintain a steady drug level in his blood by giving analgesics around the clock. To avoid sleep interruptions, the patient may want to double the dose taken closest to bedtime. Here’s a common stepped approach for keeping the pain in check.

Step 1

For patients with mild to moderate pain (pain rating from 1 to 3) a nonopioid drug such as those listed here is the best choice. Mild pain should be relieved within 12 hours.

acetaminophen: suppositories, tablets, capsules, gel-caps, or oral solution

aspirin: tablets or suppositories

ibuprofen or other NSAID: tablets, capsules, or suspension

Step 2

If the pain persists or increases (pain rating from 4 to 6), add a mild opioid to acetaminophen or an NSAID. Moderate pain should be relieved within 8 hours.

Combunox (ibuprofen/oxycodone): tablets

Darvocet or Trycet (acetaminophen/propoxyphene): tablets

Darvon (propoxyphene): tablets, capsules

Darvon compound (aspirin/propoxyphene/caffeine): pulvules

Lortab or Vicodin (aspirin/codeine): tablets, capsules, oral solution, elixir, caplets

Percocet or Roxicet (acetaminophen/oxycodone): tablets, capsules, caplets, oral solution

Percodan or Roxiprin (aspirin/oxycodone): tablets

Tylenol #2, #3, or #4 (acetaminophen/codeine): tablets, oral solution, suspension, elixir

Ultram (tramadol): tablets

Vicoprofen (ibuprofen/hydrocodone): tablets

Nondrug interventions for pain

Sometimes a simple position change or back rub is all that’s needed to reduce pain. These comfort measures can also increase the effectivenesss of analgesics. Other nondrug measures include:

Acupressure

Acupuncture

Aromatherapy

Gentle massage

Humor

Music

Pets

Prayer and meditation

Propping painful legs or arms on pillows

Therapeutic touch

Use of a heating pad, ice pack, or both

Because acetaminophen can cause liver damage or failure, especially in patients who consume alcohol, don’t give more than 4 grams (4,000 mg) daily. If the patient takes an analgesic that contains aspirin, make sure to assess him for stomach upset and increased bleeding.

Step 3

If pain is severe (pain rating from 7 to 10), the patient will need a stronger opioid, such as those listed here. Start with a short-acting form. Severe pain should be relieved within 4 hours.

hydromorphone: tablets, extended-release capsules, oral solution, suppositories; I.M., I.V. or subcutaneous injection; I.M., I.V., or subcutaneous high-potency injection

morphine sulfate: tablets; extended-release tablets; controlled-release tablets; sustained-release capsules; oral solution; concentrated oral solution; suppositories; I.M., I.V., or subcutaneous injection; extended-release epidural injection; epidural and intrathecal injection

oxycodone: immediate-release capsules and tablets, controlled-release tablets, oral solution, concentrated oral solution

For breakthrough pain, each dose should be 10%to 15%of the total daily dose. Usually, doses are ordered q 1 hour, p.r.n. Here are some examples of doses designed for breakthrough pain:

morphine 5 mg q 4 hours P.O. around-the-clock with 5 mg q 1 hour P.O. p.r.n. for breakthrough pain

oxycodone 5 mg q 4 hours P.O. around-the-clock with 5 mg q 1 hour P.O. p.r.n. for breakthrough pain.

hydromorphone 1 mg q 4 hours P.O. around-the-clock regularly with 0.5 to 1 mg q 1 hour P.O. p.r.n. for breakthrough pain.

Meperidine (Demerol) produces a metabolite that’s toxic to the nervous system. Don’t give it to patients with end-stage cancer or other patients in end-of-life care.

Fentanyl (Duragesic) is another commonly used opioid for chronic pain because of its ease of use (transdermal patch) and the long period between doses (usually 72 hours). If the patient currently receives morphine and you need to switch to fentanyl, use an equianalgesic scale to establish the correct dosage. (See Converting to fentanyl.)

To determine the patient’s total morphine dose, you’ll have to include both the doses he receives around the clock and the doses he receives for breakthrough pain. In other words, if the patient takes morphine 60 mg P.O. q 4 hours plus one 30-mg breakthrough dose in 24 hours, perform this computation:

60 mg × 6 = 360 mg + 30 mg = 390 mg total morphine in 24 hours.

Then, using an equianalgesic chart, you’ll see that he can switch to a 100-mcg fentanyl patch. Keep in mind, however, that because the equianalgesic chart covers wide ranges of morphine doses per fentanyl dose, some hospice agencies use a more specific conversion ratio. Here’s how to do it:

First, determine the fentanyl dose by dividing the morphine dose by 100 using the ratio method below.

100 : 1 :: 390 : x. Solving for x, the result is 39 mg.

Now, convert milligrams to micrograms: 39 × 100 = 3,900 mcg.

Divide that by 24: 3,900/24 = 162.5 mcg fentanyl.

Using this formula, the patient should be using either a 150-mcg or a 175-mcg fentanyl patch, depending on the pain assessment.

Adverse effects

Although morphine is the drug closest to our body’s own natural painkillers, it isn’t without adverse effects. All opioids share these common secondary reactions. Watch for and be prepared to treat these reactions.

Constipation

Morphine almost always causes constipation; start treating it as soon as morphine therapy starts. Giving a stool softener and fiber laxative once or twice daily may be sufficient if the patient still has reasonable food and fluid intake. Stronger preparations such as lactulose (Chronolac) may be needed and can be adjusted easily to the patient’s bowel status. Some patients need a regular regimen of oral laxatives plus a periodic rectal preparation, such as bisacodyl suppository.

Sleepiness

Usually, sleepiness goes away as the patient’s body grows accustomed to the dosage. It may recur temporarily at each dosage increase. If it persists, the morphine may not be causing it. Instead, the patient may have ongoing drowsiness from progression of the illness itself. (See A time to listen, page 108.)

Converting to fentanyl

If you’re converting a patient from morphine to fentanyl, use this equianalgesic scale to help you make the switch. Don’t forget that the morphine dose is in milligrams and the fentanyl dose is in micrograms.

| Morphine (mg) | Fentanyl (mcg) |

|---|---|

| 60–134 | 25 |

| 135–224 | 50 |

| 225–314 | 75 |

| 315–404 | 100 |

| 405–494 | 125 |

| 495–584 | 150 |

| 585–674 | 175 |

| 675–764 | 200 |

| 765–854 | 225 |

| 855–944 | 250 |

| 945–1,034 | 275 |

| 1035–1,124 | 300 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access