Pain Theory

TERMS

acute pain

central nervous system

chronic pain

depression

intermittent claudication

neuropathic pain

neurotransmitters

nociceptors

objective

pain

peripheral arterial disease

peripheral nervous system

phantom pain

prostaglandins

referred pain

subjective

superficial pain

visceral pain

QUICK LOOK AT THE CHAPTER AHEAD

Pain is a subjective symptom experienced by individuals for a wide variety of reasons. Pain can be acute or chronic. Manifestations of pain can be inconsistent, varying with the cause, site and type of pain, as well as with patient-related variables.

Physiology of pain includes both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS), mediated through a variety of chemical substances called neurotransmitters. Pain management includes methods addressing both the CNS and the PNS.

Different types of pain include superficial, visceral, somatic, neuropathic and pain resulting from metabolic need or metabolic excess.

CASE STUDY

Ms. P., a 27-year-old married woman, comes to the emergency department of a local community hospital complaining of severe pain in her back and right flank. She is pale and nauseated, and her skin is warm and dry. Skin turgor is poor. She appears dehydrated. On assessment, she localizes her pain in the right flank as well as in the central portion of her back. It is unrelieved by changing position. Prior to coming to the hospital, she attempted to relieve the back pain through use of a heating pad. This was not successful.

Pain is a universally experienced phenomenon. It is subjective, a perception of the individual. Pain has been described as being just what the individual experiencing it says it is. Being a subjective experience, severity, duration, and meaning are determined by the individual. Pain is characterized by some objective signs and symptoms; however, it cannot be assumed that all people will exhibit these objective signs as a part of the pain experience. Clients describe the experience as acute or chronic discomfort. In descriptive assessment, the type and severity of the pain are often characterized as agony, pulling, pressure, burning, stinging, searing, stabbing, dull, aching, and so on. More than one type, sensation, or source of pain may coexist for one client at one time. It is a phenomenon that must be carefully assessed to plan interventions.

There are multiple and varied causes of pain. The experience can be related to trauma (major or minor), stress, surgery, illness, hormonal changes, childbirth, inflammation, and ischemia. Episodes of pain occur in the client in clinical as well as nonclinical situations. Frequently, severe pain that restricts activity or otherwise interferes with daily living is the precipitating factor for seeking medical care. When daily living is not seriously affected, self-treatment for pain is a common choice. When self-care is not successful, medical care may become an alternative choice.

Acute Pain or Chronic Pain?

Acute pain usually occurs with an identifiable precipitating factor. It varies in type and severity, and it may be constant or intermittent. Description of pain as acute does not refer to severity; rather, it describes the time period in which the particular pain is experienced. Episodes of pain that are resolved in less than 6 months are considered to be acute. Chronic pain refers to episodes that take more than 6 months to resolve. This does not presume that relief for acute or chronic pain cannot be successfully initiated within that time frame. Rather, it indicates that the cause or precipitating factor is identified and successfully eliminated or controlled before or after a 6-month time span.

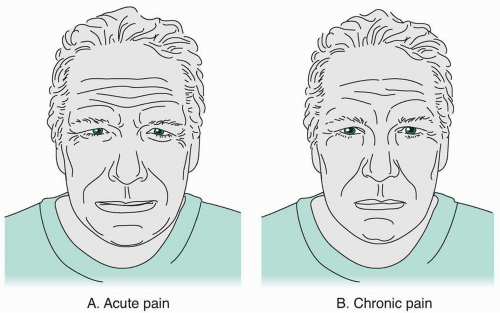

Symptoms of acute and chronic pain frequently differ on objective assessment (Figure 1-1). The client in acute pain more closely fits the stereotypical or traditional picture of pain. Activities such as grimacing, splinting, guarding, moaning, or crying are often observed, although they may not directly correlate with severity. The client with acute pain usually exhibits a change in routine level of activity, with progressively severe pain preventing successful completion of activities of daily living (ADLs). The client may become anxious or agitated with acute pain. This type of pain is seen as predictable. It can usually be controlled or eliminated; it is expected and self-limiting with the cause or precipitating factor. Physical assessment of the client in acute pain usually reveals an increase in vital signs, specifically pulse and respirations (hyperactivity of the autonomic nervous system). Blood pressure may be seen to either increase or decrease, with a decrease indicating potential for shock. The client in acute pain is frequently pale and diaphoretic.

Figure 1-1 A. Acute pain denoted by obvious distress, autonomic symptoms, grimacing, and crying. B. Chronic pain denoted by not-so-obvious distress and flattened affect. |

Chronic pain manifests quite differently. The client does not look like someone in pain by traditional standards. The chronicity of the painful experience has caused the expression of pain to differ, especially in relation to restrictions with ADLs. Chronic pain is not predictable and has no anticipated end point. It is frequently undertreated because the healthcare provider does not assess the client as being in significant pain. There is commonly no remarkable deviation in vital signs or other observable physiological parameters upon assessment. Fatigue and social isolation are common sequelae of chronic pain. Rather than grimacing or agitation, the client in pain may exhibit slack facial features, reduced activity levels, and a flattened affect. Depression may accompany chronic pain. It is essential for the healthcare provider to recognize, acknowledge, and treat chronic pain as the client describes it. Treatment of chronic pain includes long-term use of prescribed interventions. With this in mind, interventions should be cost effective or affordable, easy to understand and practice, readily available, and believable. By considering these factors for each individual client, compliance with treatment will be more commonly assured. It is also important to frequently reassess the chronic pain client.

The sensation of pain involves both the peripheral and central nervous systems. It is primarily a warning signal to avoid injury. Response to pain is often reflexive. The central nervous system mediates other responses.

Specialized nerve cells, called nociceptors, are sensory receptors found in skin, muscle, viscera, and connective tissue. These nerve cells respond to stimulation caused by thermal, mechanical, or chemical injury. The response is release of chemical mediators including prostaglandins. The chemical mediators cause the nociceptor to “fire,” carrying the pain impulse to the spinal cord. These impulses travel along afferent nerve fibers, either myelinated A-delta fibers or unmyelinated C fibers.

Specialized nerve cells, called nociceptors, are sensory receptors found in skin, muscle, viscera, and connective tissue. These nerve cells respond to stimulation caused by thermal, mechanical, or chemical injury. The response is release of chemical mediators including prostaglandins. The chemical mediators cause the nociceptor to “fire,” carrying the pain impulse to the spinal cord. These impulses travel along afferent nerve fibers, either myelinated A-delta fibers or unmyelinated C fibers.

Gate Control Theory

The gate control theory, first proposed by scientists in 1965, argues that pain is not transmitted directly from the spinal cord to the central nervous system. Rather, a complex nerve structure in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord can inhibit transmission of the pain message to the brain. These gates operate by means of various neurotransmitters including substance P and somatostatin. Prevention of transmission to the brain also prevents the recognized sensation of pain. The response to the injury is reflexive, and the source of the unpleasant stimulus is eliminated. The stimulus only becomes pain as it is sensed consciously.

Sensory information from various areas within the body may converge at spinal neurons. This convergence is responsible for the sensation of referred pain, the pain that is perceived in a part of the body other than where the injury or stimulus has originated. By utilizing the gates in the spinal dorsal horns, a variety of methods to ‘close the gate’ to painful stimuli are utilized to relieve or prevent pain.

There is a wide variety of pain and pain sensations. The variety is a product of the multiple causes of pain as well as the unique responses to painful stimuli, especially the components of higher central nervous system responses. Pain, as discussed earlier, can be acute or chronic. Symptoms of these types differ, as do the potential interventions for control and

relief. The emotional reaction of the client also changes in response to acuity or chronicity.

relief. The emotional reaction of the client also changes in response to acuity or chronicity.

Superficial Pain

Superficial pain is extremely common across the lifespan. It is the result of stimulation of the most superficial nociceptors in cutaneous tissue, such as skin or mucous membranes. These areas are rich in afferent fibers, since one of their functions is to gather information about the world outside of the organism. Given the wealth of receptive nervous tissue in these areas, superficial pain can be experienced by the individual as quite severe or intense. Superficial or cutaneous pain may result from mechanical injury, such as scraping, abrasion, or compression (pinching the tissue). Thermal injury, including both heat and cold, is another cause of superficial pain. Finally, chemical injury causes this type of pain. It is frequently described in two distinct patterns: the first, with rapid, acute onset at the time of injury, is frequently a sharp piercing or stinging sensation; the second is cutaneous pain that arises well after the painful event and may be a deeper burning sensation that is longer-lasting and more difficult to relieve. It is easily localized by the client, who can usually identify the exact location as well as the precipitating event. Potential interventions may be local—such as the application of cold, heat, or pressure—or systemic. Superficial pain is not always accompanied by obvious signs of injury. When there is obvious injury, fear, anxiety, or other intense emotions may complicate the pain and the efforts to offer relief.

Superficial pain is characterized in two distinct patterns: rapid, acute onset at the time of injury, consisting of a sharp piercing or stinging sensation, or cutaneous pain, occurring well after the painful event, consisting of a deep burning sensation that is longer-lasting and more difficult to relieve.

Superficial pain is characterized in two distinct patterns: rapid, acute onset at the time of injury, consisting of a sharp piercing or stinging sensation, or cutaneous pain, occurring well after the painful event, consisting of a deep burning sensation that is longer-lasting and more difficult to relieve.Visceral Pain

Pain that arises from stimulation of deeper nociceptors may be visceral (sometimes called organ pain) or somatic (structural pain). Visceral pain can arise in the thoracic, abdominal, pelvic, or cranial cavities. It is diffuse, poorly localized, and frequently difficult to identify with diagnosis.

Symptoms commonly associated with visceral pain are indicative of autonomic nervous system activity. They include pallor, diaphoresis, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. There is often a significant increase in the client’s blood pressure. Visceral pain may not come from the specific organ system where damage has occurred but may be caused by pressure or inflammation in surrounding tissues. One excellent example is abdominal pain accompanying intestinal disorders such as diverticulitis or colon cancer. The inside of the large intestine is poorly innervated with afferent fibers. As a matter of fact, patients with ostomies may have no sensation at the mucous membrane portion of the stoma, which is constructed from the interior of the large intestine. Rather, abdominal pain accompanying these illnesses may arise from stimulation of afferent fibers in the omentum or abdominal wall. Another source of painful stimuli is strong muscular contractions of hollow organs such as the stomach or bladder, resulting in visceral pain.

Visceral pain is described as deep, aching, cramping, or intense pressure. It is this type of pain that is frequently “referred” to other areas of the body. Referred pain is a sensation that actually arises in one organ system or area of the body but is perceived by the client to be occurring in another area (Figure 1-2).

One example of referred pain is back pain as part of the symptom set of cholecystitis. Sensation of pain at an area other than its source may complicate timely diagnosis or delay the client’s attempts to access medical care. The client experiencing back pain associated with cholecystitis may first use self-care methods such as heat, massage, and over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to manage the pain.

Somatic Pain

Somatic or structural pain is more easily localized by the client and is frequently associated with trauma or activity. It may arise in muscles, joints, bones ligaments, tendons, or fascia. The client’s description of the pain may vary from sharp and severe to dull and achy. Somatic pain may be constant or intermittent, and the client often relates it to activity or positioning. Structural tissues may stimulate afferent nerve fibers because of traumatic injury such as tearing or crushing. Afferent fibers may also be stimulated by pressure, such as the result of tumor invasion,

swelling, venous congestion, or chemical irritation, as in rheumatoid arthritis. Deeper somatic pain is often more poorly localized and may be experienced and reported by the client as referred pain. Clients will frequently attempt self-care measures to relieve somatic pain. This type of pain may indicate conditions that are progressive. Early intervention in these cases can prevent further injury or complications.

swelling, venous congestion, or chemical irritation, as in rheumatoid arthritis. Deeper somatic pain is often more poorly localized and may be experienced and reported by the client as referred pain. Clients will frequently attempt self-care measures to relieve somatic pain. This type of pain may indicate conditions that are progressive. Early intervention in these cases can prevent further injury or complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree