Osteoarthritis

The most common form of arthritis, osteoarthritis causes deterioration of the joint cartilage and formation of reactive new bone at the margins and subchondral areas of the joints. This chronic degeneration results from a breakdown of chondrocytes, most often in the hips and knees.

Osteoarthritis occurs equally in both sexes after age 40. The earliest symptoms appear in middle age and progress with advancing age.

Depending on the site and severity of joint involvement, disability can range from minor limitation of the fingers to near immobility in those with hip or knee involvement. Progression rates vary; joints may remain stable for years in the early stage of deterioration.

Causes

Primary osteoarthritis may be related to aging, although researchers don’t understand why. This form of the disease seems to lack any predisposing factors. In some patients, however, it may be hereditary.

Secondary osteoarthritis usually follows an identifiable event—most commonly a traumatic injury or congenital abnormality, such as hip dysplasia. Endocrine disorders

(such as diabetes mellitus), metabolic disorders (such as chondrocalcinosis), and other types of arthritis also can lead to secondary osteoarthritis.

(such as diabetes mellitus), metabolic disorders (such as chondrocalcinosis), and other types of arthritis also can lead to secondary osteoarthritis.

Signs of osteoarthritis

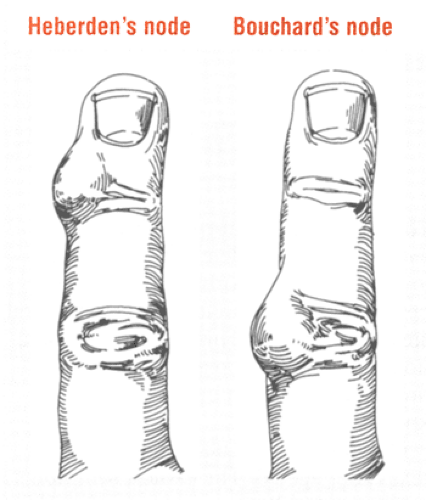

Heberden’s nodes (see illustration below, left) appear on the dorsolateral aspect of the distal interphalangeal joints. Usually hard and painless, these bony and cartilaginous enlargements typically occur in middle-aged and elderly patients with osteoarthritis.

Bouchard’s nodes (see illustration below, right), which are similar to Heberden’s nodes but less common, appear on the proximal interphalangeal joints.

Complications

Osteoarthritis may cause flexion contractures, subluxation and deformity, ankylosis, bony cysts, gross bony overgrowth, central cord syndrome (with cervical spine osteoarthritis), nerve root compression, and cauda equina syndrome.

Assessment

The patient usually complains of gradually increasing signs and symptoms. He may report a predisposing event, such as a traumatic injury. Most commonly, the patient has a deep, aching joint pain, particularly after he exercises or bears weight on the affected joint. Rest may relieve the pain.

Additional complaints include stiffness in the morning and after exercise, aching during changes in weather, a “grating” feeling when the joint moves, contractures, and limited movement. These symptoms tend to be worse in patients with poor posture, obesity, or occupational stress.

Inspection may reveal joint swelling, muscle atrophy, deformity of the involved areas, and gait abnormalities (when arthritis affects the hips or knees). Osteoarthritis of the interphalangeal joints produces hard nodes on the distal and proximal joints. Painless at first, these nodes eventually become red, swollen, and tender. The fingers may become numb and lose their dexterity. (See Signs of osteoarthritis.)

Palpation may reveal joint tenderness and warmth without redness, grating with movement, joint instability, muscle spasms, and limited movement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree