Nutrition

Susan Luck

Nurse Healer OBJECTIVES

|

Theoretical

Learn the definitions of terms in this chapter.

Differentiate between the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) and the optimal daily allowance (ODA).

Develop a plan that combines good nutrition with a healthy lifestyle.

Learn the benefits of healthy eating for wellness promotion and disease prevention.

Explore the nurse’s role as coach in behavioral and dietary change.

Clinical

Observe the meaning of foods in different cultural traditions.

Listen to the client/patient story around health and nutrition.

Identify nutritional foods that support the client/patient healing process.

Use open-ended questions to learn more from clients about eating habits and health behaviors.

Increase knowledge of current nutrition research.

Personal

Assess the quality of your food intake and note how it increases or decreases your energy level at work.

Heighten your awareness of the way in which what you eat affects how you feel.

Examine your eating patterns and the meaning of food in your life.

Explore new foods and food preparation to support your health and well-being.

Plan a day’s menu, asking yourself, “What does my body need to enhance my wellness?”

Explore mindful eating practices.

Prepare foods to bring to your workplace to support your health goals.

Find a nurse coach and enter into a coaching agreement to reach desired nutrition goals.

Employ strategies to improve nutrition in your workplace.

DEFINITIONS

Antioxidants: Substances that limit free radical formation and damage by stabilizing or deactivating free radicals before they attack cells.

Diabesity: A popular term for the common clinical association of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity.

Epigenetics: The study of changes produced in gene expression caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence.

Free radicals: Electrically charged molecules with an unpaired electron capable of attacking healthy cells in the body, causing them to lose their structure and function.

Glycemic index: An index that classifies carbohydrate foods according to their glycemic response (effect on blood glucose levels), which varies with fiber content, starch structure, food processing, and presence of proteins and fats.

HDL: High-density lipoprotein form of cholesterol associated with reduced risk of atherosclerosis.

Homocysteine: An amino acid found in the blood and intermediate product of methionine metabolism.

Leptin: A peptide hormone neurotransmitter produced by fat cells and involved in the regulation of appetite.

LDL: Low-density lipoprotein form of cholesterol strongly associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis.

Metabolic syndrome: A collection of heart disease risk factors that increase the chance of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. The condition is also known by other names including Syndrome X, cardiometabolic and insulin resistance syndrome.

Mineral: An inorganic trace element or compound that works in synergy with other compounds and is essential for human life.

Nutrigenomics: The study of the effects of foods and food constituents on gene expression. It is about how our DNA is transcribed into mRNA and then to proteins and provides a basis for understanding the biological activity of food components.

Nutraceuticals: Food, or parts of food, that provide medical or health benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease.

Obesogens: Identifiable industrial pollutants contributing to the obesity epidemic by increasing fat cells in the body and altering metabolism and feelings of hunger and fullness.

Optimal nutrition: Adequate intake of nutrients for health promotion and disease prevention.

Organic food: Food from plants and animals that have been grown without the use of synthetic fertilizers or pesticides, and without antibiotics, growth hormones, and feed additives.

Phytochemicals: Biologically active compounds found in foods and plants.

Phytoestrogens: Family of compounds found in plants that have some estrogenic or antiestrogenic activity.

Probiotic: Formulation containing beneficial living microorganisms that maintain health as part of the internal ecology of the digestive tract.

Vitamin: An organic substance necessary for normal growth, metabolism, and development of the body; acts as a catalyst and coenzyme, assisting in many chemical reactions while nourishing the body.

Xenoestrogens: Synthetic, environmental, hormone-mimicking compounds found in many pesticides, drugs, plastics, and personal care products.

▪ CURRENT NUTRITION THEORY AND RESEARCH

Nutrition is integral to maintaining health throughout the life cycle and has a profound influence on disease prevention, health maintenance, and the aging process. Dietary habits play a central role in almost all health problems seen today including inflammation and pain, digestive and gastrointestinal disturbances, allergies and food sensitivities, fatigue, mood disorders, and immune dysfunction. Food and nutrients are no longer viewed merely as providing substances whose absence would produce disease, but as having a positive impact on an individual’s overall health including physical performance, aging process, cognitive function, energy levels, and daily quality of life.

It is common knowledge that foods produced today are processed and denatured, depleted of nutrients, and often contain toxic chemicals including additives, preservatives, pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, and many other residues. The changes to our food supply contribute to a rising number of chronic health issues including learning disabilities, obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, heart disease, hypertension, immune and autoimmune diseases, and various cancers.1

According to several recently published studies, evidence-based guidelines regarding recommendations on lifestyle and healthy nutrition as a primary preventive intervention demonstrate consistent results. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of primary prevention services is

proven. Health promotion and disease prevention are emerging as a national strategy and nurses in all healthcare settings are in a key position to use their professional skills to coach and educate individuals and communities in nutrition and lifestyle changes that affect long-term health goals and health policy. Integrating nurse coaching into clinical practice is a new direction for nurses in a patient-centered care model.

proven. Health promotion and disease prevention are emerging as a national strategy and nurses in all healthcare settings are in a key position to use their professional skills to coach and educate individuals and communities in nutrition and lifestyle changes that affect long-term health goals and health policy. Integrating nurse coaching into clinical practice is a new direction for nurses in a patient-centered care model.

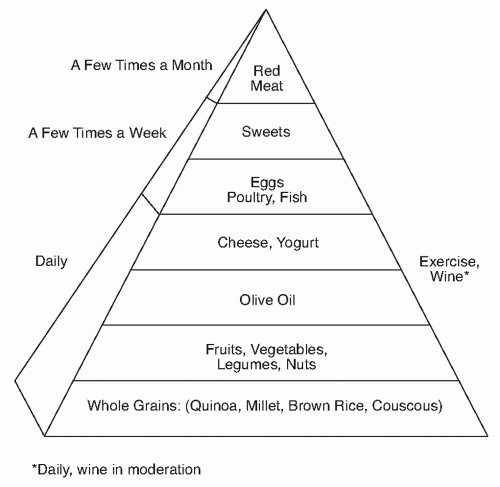

The evidence-based science of nutrition and lifestyle interventions for preventing or treating chronic disease demonstrates the powerful, costeffective, and critical role nutrition plays in the promotion and restoration of health. Current research supports healthful dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, which includes whole grains, legumes, nuts, vegetables, fruits, olive oil, and fish and is associated with a decrease in chronic disease and death from all causes. The harmful effects of trans and certain saturated fats, refined carbohydrates, high-fructose corn syrup, and many food additives are well documented in the medical literature.2

Current Health Crisis

According to a recent American Heart Association report completed in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health, in 2009 the economic costs of cardiovascular disease and stroke in the United States were estimated at $475.3 billion. In this report, nutrition and dietary intake and their relationship to the chronic disease patterns burdening the nation’s health and healthcare system, including metabolic syndrome, obesity, and diabetes, are highlighted.3

Since 1980, obesity prevalence among children and adolescents has almost tripled. It is estimated that 66% of adults in the United States, 48 million Americans, are overweight, and 50 million are now classified as obese.

Obesity and metabolic syndrome have the potential to impact the incidence and severity of cardiovascular pathologies, with grave implications for worldwide healthcare systems. The metabolic syndrome is characterized by visceral obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, chronic inflammation, and thrombotic disorders contributing to endothelial dysfunction and, subsequently, to accelerated atherosclerosis. Obesity is a key component in development of the metabolic syndrome and it is becoming increasingly clear that a central factor in this is the production by adipose cells of bioactive substances that directly influence insulin sensitivity and vascular injury

According to the CDC, overweight and obese are labels for ranges of weight that are greater than what is generally considered healthy for a given height. For adults, overweight and obesity ranges are determined by using weight and height to calculate a number called the body mass index (BMI). It can also be defined as weighing in excess of 40 pounds more than ideal body weight. The national prevalence of overweight and obesity is monitored using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). According to the most recent survey, 17% of (or 12.5 million) children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years are obese. Healthy People 2010 identified overweight and obesity as leading health indicators and as indicators of future health risks and called for a reduction in the proportion of children and adolescents who are overweight or obese.4 Obesity reduces life expectancy while increasing the risk of illness and death from a range of other diseases. It is now so common in adults and children that the World Health Organization characterizes this condition as a global epidemic.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a preventable disease and a growing public health problem. Epidemiologic and interventional studies suggest that weight loss is the main driving force to reduce diabetes risk. Landmark clinical trials of lifestyle changes in subjects with prediabetes have shown that diet and exercise leading to weight loss consistently reduce the incidence of diabetes.5

Energy imbalance is the immediate cause of obesity: a combination of excess dietary calories and a lack of physical activity. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in April 2010 concludes that sugar intake significantly contributes to ill health and specifically increases triglycerides and cholesterol levels. Hypertriglyceridemia is a common lipid abnormality in persons with visceral obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes

Researchers at Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined the added sugar intake and blood fat levels in more than 6,100 adults. Participants consumed an average of 21.4 teaspoons

of added sugars a day, or more than 320 calories a day from these sources.5 According to the report, type 2 diabetes and obesity hold longterm health implications for the U.S. population: “Obesity is a contributing cause of many health problems, including heart disease stroke, diabetes, and some types of cancer.” Statistically, these are some of the leading causes of death in the United States.

of added sugars a day, or more than 320 calories a day from these sources.5 According to the report, type 2 diabetes and obesity hold longterm health implications for the U.S. population: “Obesity is a contributing cause of many health problems, including heart disease stroke, diabetes, and some types of cancer.” Statistically, these are some of the leading causes of death in the United States.

Other symptoms and health risks attributed to obesity include sleep apnea, asthma and breathing problems, limited mobility, inflammation, and early deterioration of joints leading to arthritis, and osteoporosis and hip fractures. Obesity can cause problems during pregnancy and indicates a higher risk for obesity in children of obese parents.6

Emerging Research in the Study of Obesity

Recent research focuses on how environmental toxins, described as obesogens, are stored in fat tissue and can influence and interfere with healthy fat cell signaling and fat metabolism and how overeating can interfere with cell signaling messengers that control feelings of satiety after eating. For healthy fat metabolism, leptin, an adipocyte-derived hormone, plays an essential role in the maintenance of normal body weight and energy expenditure, as well as glucose homeostasis. Leptin resistance occurs in those who are chronically overweight. The role of leptin in the fat cells is to reduce appetite and stimulate fat burning. The relationship between leptin and perceived hunger, and on the eating behavior of leptin-deficient individuals appears to be blocked in chronically overweight individuals as they develop leptin resistance, making losing weight increasingly difficult, if not impossible.7

Fat also regulates the processes by which the body burns fuel for energy, especially in muscle. Adiponectin, another hormone-like chemical, plays a central role in the biology of fat and is normally produced to curb appetite and spark the burning of fat. But unlike leptin, which remains present but stops functioning, chronically overweight individuals have an adiponectin deficiency. Many adipokines are also mediators of inflammation and promote and encourage the inflammatory response, which further affects fat metabolism and homeostasis.8 Weight loss is associated with reduced inflammation systemically.9

Routine exposures to human-made chemicals may also increase an individual’s risk of obesity. The obesogen hypothesis proposes that perturbations in metabolic signaling that result from exposure to environmental chemicals known as endocrine disruptors, and stored in the body’s adipose tissue, may further exacerbate the effects of imbalances, resulting in an increased susceptibility to obesity and obesity-related disorders.10 These markers indicate the potential for nutritional coaching for behavioral change to improve metabolism, cellular communication, and promote long-term health.

Obesity is on the minds of health policy analysts and healthcare providers, nationally and globally. According to the CDC report, “Obesity is a complex problem that requires both personal and community action.” The report goes on to mandate that people in all communities should be able to make healthy choices.

As part of a health strategy and health care policy to promote lifestyle behavioral change, nurses as coaches are in a prime position to guide and motivate individuals toward healthy behaviors. Effective health promotion programs include awareness practices, exercise, behavioral motivation for change, and nutrition education. Comprehensive effective nutrition programs integrate coaching skills for the patient/client to set attainable goals. This process is a gradual and highly individualized process for reversing patterns that can eventually lead to chronic disease.

Effective therapeutic nutritional guidelines honor the totality of the individual. An individual’s metabolism, environment, genetics, emotional health, social networks, and life stressors must be considered in evaluating nutritional needs and nutritional goals. Beliefs, attitudes, eating patterns, food choices and culinary styles are deeply embedded in one’s cultural, physiological, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and socioeconomic needs and must be considered for whole person healing. Listening to an individual’s story is central to guiding behavioral change around food.11

From an evolutionary and cultural perspective, our modern-day food supply has been dramatically altered, although our biological nutrient needs have not. The human diet remained constant for thousands of years but has radically changed in the past few decades. It now becomes painfully clear that our modern dietary habits influence our health and well-being. For example, we know that food composition and macronutrient content are essential for biochemical processes, working synergistically to produce energy on a cellular level. Without proper nutrient synergy and healthy cellular communication, the end result is diminished function that often results in decreased energy output, inflammation, and lowered immune response. Essential macronutrients and micronutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals, and essential fatty acids.11

Food as Energy

The body is an energy flow system and cells must live in harmony in the extracellular matrix. Over time, nutritional deficiencies create disharmony within the cellular structure and diminish energy exchange within cells, essential for healthy cell signaling and healthy cell function. Overt symptoms of nutrient deficiency are the result of a long chain of reactions in the body. When an individual consumes a nutrient-deficient diet, the initial reactions occur on a molecular level. First, enzymes that are dependent on the deficient nutrients become depleted. This depletion brings about changes within cells. The deficiencies may continue for many years until the body can no longer carry out its normal functions. Eventually, overt signs and symptoms appear, even though the deficiency may still be considered subclinical because routine laboratory tests do not necessarily uncover nutritional deficiencies. Nevertheless, these unseen deficiencies can lead to a broad range of nonspecific conditions that can diminish an individual’s overall quality of life. Undiagnosed, nutrient deficiencies over many years leave the body more vulnerable to illnesses to which the individual may be genetically predisposed and to immune system compromise. Yet, as resilient beings, even when health is compromised, we can reprogram our cells and create an internal and external healing environment to restore health and balance.

Debate continues over the most efficient “diet” for weight loss and overall health. Advocates of high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets including the Atkins Diet are challenged by vegan-type diets consisting of high amounts of complex carbohydrates and high intake of fruits and vegetables. A study of more than 100,000 people over more than 20 years, the Nurses’ Health Study, concludes that a low-carbohydrate diet high in vegetables and with a larger proportion of proteins and oils coming mostly from plant sources decreases mortality. In contrast, a lowcarbohydrate diet with largely animal sources of protein and fat increases mortality.13

An Integrative Functional Health Model

In a nutritional coaching model, the client moves beyond the concept of a “diet” to set attainable goals leading to a healthier lifestyle, new behaviors, and improved health outcomes. As nutrition research and information reach the public and the existing healthcare model, there is a hunger for a new paradigm that explores and examines the underlying causes of disease. Functional medicine is an emerging field in medicine with a special emphasis on nutrition and lifestyle interventions. For holistic nurses, in a patient centered care, model health is viewed as a positive vitality, representing more than the absence of disease. Through maintaining balance of a complex web of physiologic, cognitive/emotional, and physical processes, health and well-being are achieved

Adapted from Functional Medicine, an Integrative Functional Health Model (IFHM) is congruent and compatible with holistic nursing philosophy and practice.

The IFHM is a unique nursing model that expands on the functional medicine model, integrating the art and science of nursing and nursing theories, and builds on the holistic nursing process. The IFHM views health and balance as a dynamic interaction and interconnectedness between the individual and his or her environment. In this model, the nurse coach is a partner, understanding the therapeutic use of self in relationship-centered care to promote health and well-being. Coaching strategies for a healthy lifestyle integrate nutritional knowledge and nutritional coaching; they are opportunities for nurses to bring new skills and tools to the art

and science of nursing. This model moves nurses beyond understanding a client’s chemistry, diagnosis, and ailments from a medical construct and helps them view health, energy, and balance through an expanded, holistic, integrative perspective. The physical, integral, and social environment in which symptoms occur; the dietary habits of the person (present and past); the environment in which the person lives; his or her beliefs about health, illness, and diagnosis; and the combined impact of these factors on social, physical, and psychological function are all interconnected to one’s lifestyle choices and influence health outcomes. Discovery of the factors that aggravate or ameliorate symptoms and that predispose the client to illness or facilitate recovery provides for the possibilities of co-creating lifestyle and behavioral changes and establishing an integrative care plan. The nurse coach’s collaborative relationship recognizes and acknowledges the individual’s experience of health or illness and explores the totality of the individual.

and science of nursing. This model moves nurses beyond understanding a client’s chemistry, diagnosis, and ailments from a medical construct and helps them view health, energy, and balance through an expanded, holistic, integrative perspective. The physical, integral, and social environment in which symptoms occur; the dietary habits of the person (present and past); the environment in which the person lives; his or her beliefs about health, illness, and diagnosis; and the combined impact of these factors on social, physical, and psychological function are all interconnected to one’s lifestyle choices and influence health outcomes. Discovery of the factors that aggravate or ameliorate symptoms and that predispose the client to illness or facilitate recovery provides for the possibilities of co-creating lifestyle and behavioral changes and establishing an integrative care plan. The nurse coach’s collaborative relationship recognizes and acknowledges the individual’s experience of health or illness and explores the totality of the individual.

Within this larger context of the whole person, nurses increase their knowledge, understand the current nutrition science and research, and stay informed so as to evaluate and educate clients and patients. Increasing awareness, assessing the client’s relationship to nutrition and food, evaluating the client’s eating patterns and nutritional needs, assisting in developing a personalized nutrition plan and goals, and implementing effective nutritional guidelines and strategies for enhancing wellness are all part of the role of nurse coaches.

Foundations of a Nurse-Based Functional Health Model

Interconnectedness: Includes the mind, body, and spiritual dimensions of physiologic factors. An abundance of research now supports the view that the human body functions as an orchestrated network of interconnected systems rather than as individual systems that function autonomously and without effect on each other.

Energy field principles and dynamics: An understanding of how thoughts, stress, toxic environments, and a nutrient-deficient diet can disrupt human energy fields, impair optimal functioning, and contribute to disease.

Patient-centeredness: Honors and emphasizes the individual’s unique history, beliefs, and story rather than a medical diagnosis and disease orientation.

Biochemical individuality: Recognizes the importance of variations in metabolic function that derive from unique genetic and environmental vulnerabilities and strengths among individuals.

Health on a wellness continuum: Views health as a dynamic balance on multiple levels and seeks to identify, restore, and support delete our innate reserve as the means to enhance well-being and healing throughout the life cycle.

Optimization of our internal and external healing environments: Holds the worldview that human health is the microcosm of the macrocosm in the web of life.

© 2010 Integrative Nurse Coach Certificate Program (INCCP)

Overview of Clinical Nutrition

Changes to the U.S. food supply contribute to a rising number of health problems including atherosclerosis, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and various cancers—diseases virtually unknown a hundred years ago. Basic essential nutrient requirements are unavailable for healthy cell signaling and to meet the demands and needs of people throughout the various stages of life, beginning with prenatal development and continuing into old age.

Can we get all of our nutritional needs met from the foods available today?

The Standard American Diet

Nutrient deficiencies most often result from a high intake of processed and refined foods. According to the 2009 American Heart Association report, it is estimated that the average American adult consumes 22 teaspoons of sugar a day; teens eat 34 teaspoons of refined sugar and high-fructose corn syrup each day. High-fructose corn syrup is produced by chemically converting the starch in corn to a substance that is about 90% fructose, a sugar that is sweeter than the glucose that fuels body cells and that is processed differently by the body. Fructose is metabolized primarily in the liver, which favors the formation

of fats and results in elevated triglycerides, one of the markers for increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Sweeteners permeate the food supply and are used to sweeten soft drinks, juices, jams, yogurts, and breakfast cereals, to name a few. In addition, it is estimated that more than 28% of calories in the standard American diet (SAD) consist of refined products such as white bread and white rice, deficient in 28 essential nutrients including essential vitamins (in particular the B vitamins), minerals, protein, and fiber, all contained in the whole grain prior to processing.

of fats and results in elevated triglycerides, one of the markers for increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Sweeteners permeate the food supply and are used to sweeten soft drinks, juices, jams, yogurts, and breakfast cereals, to name a few. In addition, it is estimated that more than 28% of calories in the standard American diet (SAD) consist of refined products such as white bread and white rice, deficient in 28 essential nutrients including essential vitamins (in particular the B vitamins), minerals, protein, and fiber, all contained in the whole grain prior to processing.

As the field of nutrition evolves, understandings and traditional guidelines are changing. In 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans to “promote health, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity through improved nutrition and physical activity.” With more than one-third of children and more than two-thirds of adults in the United States overweight or obese, the seventh edition of Dietary Guidelines for Americans places stronger emphasis on reducing calorie consumption and increasing physical activity.

For the first time in more than 40 years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has reissued its guidelines for nutrient needs, originally defined as the Recommended Daily Allowances (RDAs) by the U.S. Food and Nutrition Board. The RDA guidelines specified the levels of nutrients required to prevent overt symptoms of deficiency. Since their inception, the RDA guidelines have been periodically reevaluated and updated based on continuing analysis of science advances in the field. In 2010, to meet the growing healthcare crisis, the new guidelines known as Dietary Reference Intakes, or DRIs, address the questions that have been asked by experts in the field.14

Clinical Nutrition Research

As nurses expand their knowledge about nutrition, nutraceuticals and medical foods currently prescribed in conjunction with pharmaceuticals, they can assist clients in their decision-making process. including lifestyle and nutritional choices. Nurses are becoming increasingly aware of what Americans spend out of pocket on nutrition-related products: an estimated $22 billion a year, according to the National Health Statistics report in 2009. The introduction of pharmaceutical-grade omega-3 essential fatty acids (EFAs) is an example of a nutraceutical recently recommended by the American Heart Association. An extensive body of research supports the fact that by taking Omega 3 essential fatty acids, deficient in the modern food supply, they may prevent heart disease and stroke and lower triglycerides. Omega-3 EFAs have also been well researched in the treatment of arthritis, diabetes, obesity, cancer, immune and autoimmune disorders, cognitive function, and a variety of women’s health problems.16

Many epidemiologic studies report strong correlations between Western diseases and dietary habits. Mortality rates for certain cancers, as well as the incidence of cardiovascular disease, are higher among those who consume the standard American diet than among those who consume Asian, Scandinavian, or Mediterranean diets.17 (The Mediterranean diet pyramid is shown in Figure 13-1.)

Tests for elevated levels of homocysteine are routine diagnostics for assessing increased risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke. A growing body of research indicates that elevated homocysteine levels result from subclinical deficiencies of the B vitamins, including folic acid, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12. Knowledge about nutrient deficiencies and their potentially life-threatening consequences is slowly being integrated into routine physical examinations and health assessments. Two articles in the New England Journal of Medicine report that “high plasma homocysteine concentrations and low concentrations of folate and vitamin B6 play roles in homocysteine metabolism, inflammation, and cardiovascular health.” Deficiencies in many of these nutrients, especially vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), are also associated with diabetes, heart disease, depression, anxiety, and premenstrual syndrome.18

Cardiovascular disease and cancer are the two leading causes of death among women in the United States. Heart disease is responsible for 45% of all deaths among women, and nearly 40% of all females are expected to develop cancer at some point in their lifetime. Research suggests that both heart disease and cancer are strongly related to dietary habits and nutrient status. Helping women make healthy dietary and

lifestyle choices can have a significant, positive impact on their health. Recent research demonstrates the cardioprotective effects of several dietary nutrients, including fiber (both soluble and insoluble), antioxidants (vitamins C and E, beta-carotene, selenium, coenzyme Q10), folic acid, and omega-3 essential fatty acids. According to several recent studies, women can lower their risk of heart disease and heart attacks by improving their blood lipid and fatty acid profiles by consuming a combination of essential fatty acids including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) derived from fish oils and certain vegetable oils. Researchers estimate this combination produces a 43% risk reduction over a 10-year period.19

lifestyle choices can have a significant, positive impact on their health. Recent research demonstrates the cardioprotective effects of several dietary nutrients, including fiber (both soluble and insoluble), antioxidants (vitamins C and E, beta-carotene, selenium, coenzyme Q10), folic acid, and omega-3 essential fatty acids. According to several recent studies, women can lower their risk of heart disease and heart attacks by improving their blood lipid and fatty acid profiles by consuming a combination of essential fatty acids including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) derived from fish oils and certain vegetable oils. Researchers estimate this combination produces a 43% risk reduction over a 10-year period.19

EXHIBIT 13-1 Hypoglycemic Diet Plan

This diet plan assists in weight loss, blood glucose regulation, energy maintenance, nutrient needs, and satiation. The following are guidelines for a low-fat, low-refined carbohydrates, and high-protein diet.

Eliminate caffeine, soda, fruit juice, white sugar, white flour, white rice, artificial sweeteners, and white bread.

Limit fruits—two per day and divide into four portions. Avoid grapes and bananas (high in sugar).

Throughout the day, consume several small meals consisting of protein with vegetables, and complex carbohydrate if needed.

Vegetables—unlimited—raw or cooked depending on your preference (and digestion); limit beets, peas, and carrots.

SAMPLE MENU PLAN

Protein

|

Vegetables 5-7 servings daily

Salads

Steamed vegetables; fresh or frozen; avoid canned

Whole Grains + Beans= Complete Protein (represents complex carbohydrates)

Salad with grilled chicken or fish

Hummus and vegetables in whole-wheat pita

Lentil soup with gluten free rice crackers or whole grains (millet, brown rice, quinoa, whole wheat pita)

Grilled skinless chicken breast with 0.5 cup brown rice or quinoa and steamed vegetables

Tofu or black beans with brown rice and steamed vegetables

Grilled fish with half baked sweet potato and salad

Snacks: Small meals to have between meals, midmorning and midafternoon

Low-fat plain yogurt with 0.5 cup fresh fruit, whole-wheat or rice crackers with tuna salad, hummus with whole-wheat pita or vegetables

1-2 tablespoons almonds or sunflower seeds, or nut butter (almond or sesame tahini) on whole-wheat or rice crackers, leftover lunch portion

Protein Shake (Whey, Rice, Hemp, Pea, or Soy protein)

Review of Nutrient Sources

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates provide the main source of energy for all body functions, aiding in digestion, assimilation, and metabolism of proteins and fats. Carbohydrates are classified as simple and complex. Simple carbohydrates include refined white flour products, white rice, white table sugar (dextrose), honey, fruit sugars (fructose), and milk sugars (lactose). Complex carbohydrates are found in whole grains, legumes, and vegetables and contain protein, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Throughout human history foods that contain complex carbohydrates have been important diet staples in diverse cultures. Complex carbohydrates supply the body with essential nutrients and protein amino acids and provide longer-lasting energy than do simple carbohydrates.20 All animal proteins are complete, including red meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy. Complete proteins can also be obtained through plant foods including soy, lentils, amaranth, buckwheat, and quinoa. Foods can be combined to make complete proteins like pairing beans with brown rice.

Fiber

Dietary fiber is plant material that is left undigested after passing through the body’s digestive system. Fiber contains polysaccharides and can be subdivided into insoluble fiber and soluble fiber, each with a different mixture of compounds. Food sources of dietary fiber are often classified according to whether they contain predominantly soluble or insoluble fiber. Plant foods usually contain a combination of both types of fiber in varying degrees, according to the plant’s characteristics. Insoluble fiber includes pectin and cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignins.21 Insoluble fiber is present in fruits, leafy vegetables, whole grains and brans, and beans. Soluble fiber is a gelatin-like substance, such as the mucilage found in oatmeal and legumes.

Research clearly documents that the modern Western diet with its low fiber content has led to an increase in digestive problems, including diverticulitis, constipation, colon cancer, gallstone formation, and other gastrointestinal disturbances. Although dietary fiber is not digested, it increases fecal bulk and weight, making the passage of waste products more efficient and assisting in carrying toxins and metabolic byproducts through the intestines to be eliminated quickly from the system. Fiber also is important in modulating insulin response and thereby stabilizing blood glucose levels. In recent years, research into the benefits of dietary fiber has led many practitioners to recommend a low-fat, high-fiber diet for prevention of heart disease, diabetes, obesity, digestive disorders, and cancer.

According to Seymour Handler of the North Memorial Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, most of the serious diseases of the colon, including appendicitis and diverticular disease, can be linked etiologically to high levels of saturated fat and low levels of fiber in the Western diet. A diet high in saturated animal fat and low in fiber increases the risk of colon cancer. Guidelines for minimizing risk of colon cancer include reducing consumption of saturated fats and increasing consumption of fiber. Complex-carbohydrate foods offer fiber and are also good sources of protein, vitamins, and minerals.22 Fiber-rich diets help lower blood cholesterol levels and stabilize blood glucose levels and are considered heart healthy by multiple research studies. According to Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010, at least half of all grains consumed daily should be whole and unrefined. The goal for fiber is 25 grams per day for women and 28 grams per day for men. Achieving these goals may reduce a person’s risk of dying from heart disease, infections, and respiratory diseases, according to a new study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine.23

Protein

Protein is the second most plentiful substance in the body (after water) and constitutes approximately one-fifth of the body’s weight. Protein is the basic building block of the body and makes up the rigid structures such as bone, solid organs, and blood vessels. It is essential for the growth and maintenance of all body tissues, including muscle, skin, hair, nails, and eyes. Hormones, chemicals such as antibodies, and enzymes are composed of protein. Protein molecules, essentially composed of amino acids, form long chains and branched structures. Amino acids contain nitrogen, carbon, hydrogen, and sometimes sulfur. Twenty-two amino acids are required to build protein; half of these are produced in the body when adequate nutrients are available, and eight are considered essential.

Excessive protein consumption taxes the kidneys and digestive system. Because the majority of Americans consume most of their protein through animal products—a source of saturated fat as well—consumption of a large quantity of animal protein is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and breast, colon, and prostate cancers. Plant foods such as whole grains, legumes, seeds, and nuts provide excellent protein, but this protein is incomplete, and these foods must be combined with others to provide all of the essential amino acids. Protein requirements depend on an individual’s activity level, energy requirements, age, and digestive health. The recommended protein allowance for health maintenance in the United States is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. Men and women who body build require up to 1.2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day.24

Lipids

Lipids are a group of fats and fatlike substances, including essential fatty acids, that account for more than 10% of body weight in most adults. The principal function of fats is to serve as a source of energy. Stored fats also act as a thermal blanket, insulating the body and providing a protective cushion for many tissues and organs. According to the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Americans are eating less fat than they were 10 years ago. Americans now average 34% of their total daily calories (82 grams) from fat, with approximately 12% (29 grams) from saturated fats. Current dietary recommendations call for 20% of total calories from fat and less than 10% from saturated fats. The RDA for dietary fat suggested by the National Academy of Sciences to ensure the intake of essential fatty acids is 25 grams. Unsaturated fats are usually liquid at room temperature

and are derived from vegetables, nuts and seeds, soybeans, and olives. Saturated fats—found in animal products, including meat and dairy products —are generally associated with increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Foods often contain a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Fats are calorie rich and contain approximately 9 calories per gram, almost twice the calories of carbohydrates and proteins.

and are derived from vegetables, nuts and seeds, soybeans, and olives. Saturated fats—found in animal products, including meat and dairy products —are generally associated with increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Foods often contain a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Fats are calorie rich and contain approximately 9 calories per gram, almost twice the calories of carbohydrates and proteins.

Essential fatty acids are found in both monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Monosaturated fats include olive, peanut, avocado, and canola oils. Polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) are found in safflower, sunflower, corn, sesame, and soy oils. Fats can be further divided into two main classes: omega-3 fatty acids and omega-6 fatty acids. Essential fatty acids form a structural part of all cell membranes. They hold proteins in the membrane, maintain fluidity of the membrane, and create electrical potentials across the membrane, facilitating the generation of bioelectrical currents that transmit messages. Certain essential fatty acids substantially shorten the time required for the recovery of fatigued muscles after exercise by facilitating the conversion of lactic acid to water and carbon dioxide.25 Essential fatty acids act as precursors for a family of hormone-like substances called prostaglandins, which regulate many functions in the body, including inflammatory processes and immune responses. Omega-3 essential fatty acids are immune enhancing and are often deficient in the modern diet. They contain high concentrations of linoleic acid and are necessary for normal growth and development throughout the life cycle. Omega-3 essential fatty acids are found in high concentrations in fish, fish oils, flax seeds, and walnuts. Research has shown that these essential fatty acids can lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke. High concentrations of DHA are found in the brain, and a deficiency of this omega-3 essential fatty acid component can lead to impaired learning and decreased cognitive function. Other EFA deficiency symptoms include poor immune response, dry skin and hair, behavioral changes, menstrual irregularities, and arthritic and inflammatory conditions. Table 13-1 serves as a guide for general dietary goals and recommendations.26

TABLE 13-1 Dietary Goals and Recommendations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|