Neurologic care

Diseases

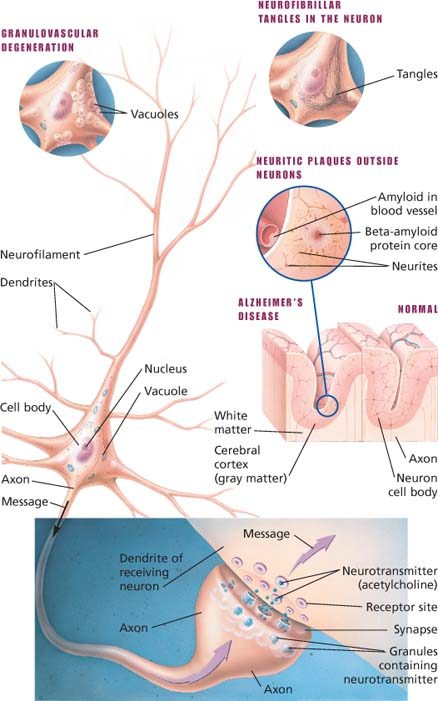

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease, also called primary degenerative dementia, accounts for more than half of all dementias. It results in memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, personality changes, disorientation, and loss of language skills; it essentially steals away the patient’s mind. Because this is a primary progressive dementia, the prognosis for a patient with this disease is poor.

The cause of Alzheimer’s disease is unknown; however, several factors are thought to be implicated in this disease. These include neurochemical factors, such as deficiencies in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, somatostatin, substance P, and norepinephrine; environmental factors; and genetic immunologic factors. Genetic studies show that an autosomal dominant form of Alzheimer’s disease is associated with early onset and early death, accounting for about 100,000 deaths per year. A family history of Alzheimer’s disease and the presence of Down syndrome are two established risk factors. Alzheimer’s disease isn’t exclusive to the elder population; its onset begins in middle age in 1% to 10% of cases.

The brain tissue of patients with Alzheimer’s disease has three hallmark features: neurofibrillary tangles, neuritic plaques, and granulovascular degeneration.

Signs and symptoms

Forgetfulness

Progressive memory loss

Difficulty learning and remembering new information

Deterioration in personal hygiene and appearance

Inability to concentrate

Progressive difficulty in communication

Severe deterioration in memory, language, and motor function

Loss of coordination

Inability to write or speak

Personality changes (restlessness, irritability)

Nocturnal awakenings

Loss of eye contact

Anxiety

Treatment

Cholinesterase inhibitors such as tacrine (Cognex), donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine (Razadyne)

N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist: nemantine (Namenda)

Antidepressants

Routine physical activity and exercise

Behavioral therapy

Nursing considerations

Overall care is focused on supporting the patient’s remaining abilities and compensating for those he has lost.

Establish an effective communication system with the patient and his family to help them adjust to the patient’s altered cognitive abilities.

Offer emotional support to the patient and his family.

Monitor the patient for periods of anxiety. Provide reassurance and note which methods are successful in calming the patient.

Provide the patient with a safe environment. Encourage him to exercise, as ordered, to help maintain mobility.

Teaching about Alzheimer’s disease

Teaching about Alzheimer’s disease

Teach the patient, his family, and caregiver about the disease and its treatments, and refer them to social services and community resources for support.

Explain the need for activity and exercise to maintain mobility and help prevent complications.

Discuss dietary adjustments for patients with restlessness, dysphagia, or coordination problems.

Emphasize the importance of establishing a daily routine, providing a safe environment, and avoiding overstimulation.

Instruct the patient, his family, and caregiver about self-care, including the importance of adequate rest, good nutrition, and private time.

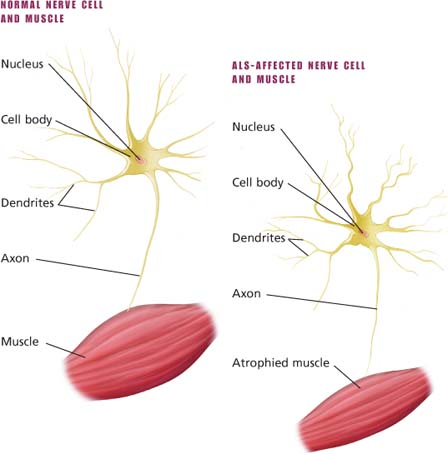

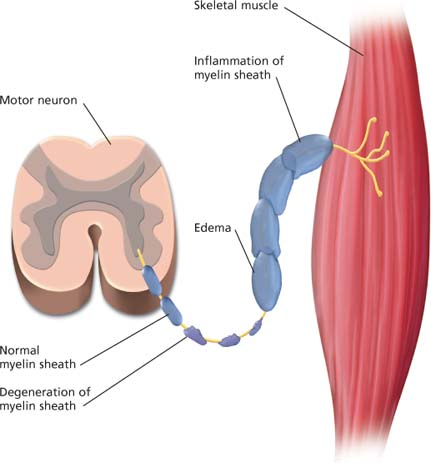

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also called Lou Gehrig disease, is the most common of the motor neuron diseases that cause muscle atrophy. Symptoms don’t develop until age 50. ALS is a chronic, progressively debilitating disease; ALS patients survive an average of 3 years.

ALS affects about 2 out of 100,000 people per year. The exact cause of ALS is unknown, but about 10% of cases have a genetic component. In these patients, it’s an autosomal dominant trait and affects men and women equally.

Other than a family member affected with the hereditary form, there are no known risk factors.

Classically, ALS affects two or more levels of motor neurons. Affected lower motor neurons lead to progressive musle weakness and atrophy. Stiffness, spasticity, and abnormally active reflexes occur when upper motor neurons are affected.

Signs and symptoms

Progressive loss of muscle strength and coordination

Fasciculations

Atrophy and weakness, especially in the muscles of the feet and the hands

Impaired speech

Difficulty chewing, swallowing, and breathing

Choking

Excessive drooling

Muscle cramps

Loss of dexterity

Uncontrolled laughing or crying

Treatment

Aims to control symptoms and provide emotional, psychological, and physical support

Riluzole (Rilutek): may increase quality of life and survival but doesn’t reverse or stop disease progression

Baclofen (Lioresal) or tizanidine (Zanaflex): helps control spasticity that interferes with activities of daily living

Sympathominetics, anticholinergics, botulinum toxin type B or salivary gland irradiation: may be needed to control saliva

Mucolytics: to thin secretions

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: may be needed early to prevent aspiration

Physical therapy, rehabilitation, and use of appliances or orthopedic intervention: may be required to maximize function

Noninvasive ventilatory support initially; mechanical ventilation may eventually be needed

Nursing considerations

Implement a rehabilitation program designed to maintain independence as long as possible.

Help the patient obtain assistive equipment, such as a walker and a wheelchair.

Arrange for a visiting nurse to oversee the patient’s status, to provide support, and to teach the patient’s family about the illness.

Depending on the patient’s muscular capacity, assist with bathing, personal hygiene, and transfers from wheelchair to bed.

Help establish a regular bowel and bladder routine.

Provide good skin care if the patient is bedridden. Turn him often, keep his skin clean and dry, and use pressure-reducing devices such as an alternating air mattress.

If the patient has trouble swallowing, give him soft, solid foods and position him upright during meals. Gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feedings may be necessary to prevent aspiration.

Provide emotional support.

Discuss end-of-life care with the patient and family. Assist with advance directives, as appropriate.

Provide information about hospice programs and local ALS support groups.

Teaching about ALS

Teaching about ALS

Teach the patient, his family, and caregiver how motor neuron degeneration affects muscles and their motor function.

Urge the patient to exercise to maintain strength in unaffected muscles.

Describe dietary changes that ease swallowing.

Demonstrate how to operate a wheelchair safely.

Explain how to prevent and manage complications such as pressure ulcers.

Help the patient develop alternative communication techniques.

Teach the patient to suction himself if he’s unable to handle an increased accumulation of secretions.

If the patient has a gastrostomy tube, show the patient’s family and caregiver how to administer tube feedings.

Discuss advance directives regarding health care decisions.

Teach the patient about his medications, including indication, dosage, administration, and possible adverse effects.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an acute, rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal form of polyneuritis that causes muscle weakness and mild distal sensory loss most often in an ascending pattern. Recovery is spontaneous and complete in about 85% of patients within 6 to 12 months, although mild motor or reflex deficits in the feet and legs may persist. The prognosis is best when symptoms clear between 15 and 20 days after onset.

Precisely what causes Guillain-Barré syndrome is unknown, but it may be a cell-mediated immunologic attack on peripheral nerves in response to a virus. The major pathologic effect is segmental demyelination of the peripheral nerves. Because this syndrome causes inflammation and degenerative changes in both the posterior (sensory) and anterior (motor) nerve roots, signs of sensory and motor losses occur simultaneously.

The clinical course of Guillain-Barré syndrome is divided into three phases:

Initial phase

Begins when the first definitive symptom appears

Ends 1 to 3 weeks later, when no further deterioration occurs

Plateau phase

Lasts several days to 2 weeks

Followed by the recovery phase, which is believed to coincide with remyelination and axonal process regrowth

Recovery phase

Extends over a period of 4 to 6 months

Patients with severe disease may take up to 2 years to recover, and recovery may not be complete

Signs and symptoms

A history of minor febrile illness (10 to 14 days before onset)

Symmetrical muscle weakness

Muscle weakness develops in the arms first (descending type) or in the arms and legs simultaneously

In milder forms, muscle weakness nonexistent or affecting only the cranial nerves

Paresthesia

Facial diplegia (possibly with ophthalmoplegia)

Dysphagia or dysarthria

Treatment

Endotracheal (ET) intubation or tracheotomy if the patient has difficulty clearing secretions or maintaining adequate ventilation

Plasmapheresis—useful in decreasing severity of symptoms, thereby facilitating a more rapid recovery

I.V. immune globulin—equally effective in reducing the severity and duration of symptoms

Nursing considerations

Monitor the patient for ascending sensory loss, which precedes motor loss.

Monitor vital signs and level of consciousness.

Assess and treat respiratory dysfunction. If respiratory muscles are weak, take serial vital capacity recordings.

Obtain arterial blood gas measurements.

Be alert for signs of rising partial pressure of carbon dioxide (such as confusion and tachypnea).

Auscultate breath sounds, turn and position the patient, and encourage coughing and deep breathing. Provide respiratory support at the first sign of dyspnea or with decreasing partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

If respiratory failure becomes imminent, assist with insertion of an ET tube.

Give meticulous skin care to prevent skin breakdown. Establish a strict turning schedule; inspect the skin (especially sacrum, heels, and ankles) for breakdown, and reposition the patient every 2 hours.

Perform passive range-of-motion exercises within the patient’s pain limits. When the patient’s condition stabilizes, change to gentle stretching and active assistance exercises.

To prevent aspiration, test the gag reflex, and elevate the head of the bed before giving the patient anything to eat or drink. If the gag reflex is absent, give nasogastric feedings until this reflex returns.

As the patient regains strength and can tolerate a vertical position, be alert for postural hypotension. Monitor blood pressure and pulse during tilting periods.

Inspect the patient’s legs regularly for signs of thrombophlebitis (localized pain, tenderness, erythema, edema, and positive Homans’ sign), a common complication of Guillain-Barré syndrome. To prevent thrombophlebitis, apply antiembolism or compression stockings and give prophylactic anticoagulants, as ordered.

If the patient has facial paralysis, give eye and mouth care every 4 hours.

Measure and record intake and output every 8 hours, and watch for urine retention.

Encourage adequate fluid intake of 2 qt (2 L) per day, unless contraindicated. If urine retention develops, begin intermittent catheterization as ordered.

To prevent or relieve constipation, offer plenty of water, prune juice, and a high-bulk diet. If necessary, give daily or alternate-day suppositories (glycerin or bisacodyl) or enemas, as ordered.

Refer the patient’s family to the Guillain-Barré Syndrome Foundation International.

Teaching about Guillain-Barré syndrome

Teaching about Guillain-Barré syndrome

Explain the disease and its signs and symptoms to the patient and his family. Explain the diagnostic tests that will be performed.

If the patient loses his gag reflex, tell him tube feeding will be needed to maintain nutritional status.

Advise family members to help the patient maintain mental alertness, fight boredom, and avoid depression. Suggest that they plan frequent visits to help distract the patient as much as possible.

Before discharge, teach the patient how to transfer from bed to wheelchair and from wheelchair to toilet or tub and how to walk short distances with a walker or a cane.

Instruct the patient’s family on how to help the patient eat and drink compensating for facial weakness, and how to help him avoid skin breakdown.

Emphasize the importance of establishing a regular bowel and bladder elimination routine.

Refer the patient for physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy, as needed.

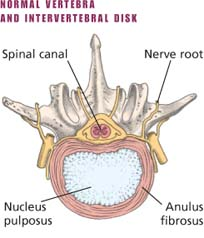

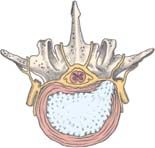

Herniated disk

A herniated disk (also known as a herniated nucleus pulposus or a slipped disk) occurs when all or part of the nucleus pulposus—an intervertebral disk’s gelatinous center—extrudes through the disk’s weakened or torn outer ring (anulus fibrosus). The resultant pressure on spinal nerve roots or on the spinal cord itself causes back pain and other symptoms of nerve root irritation.

About 90% of herniations affect the lumbar (L) and lumbosacral spine; 8% occur in the cervical (C) spine and 1% to 2% in the thoracic spine. The most common site for herniation is the L4-L5 disk space. Other sites include L5-S1, L2-L3, L3-L4, C6-C7, and C5-C6.

Lumbar herniation usually develops in people ages 20 to 45 and cervical herniation in those ages 45 or older. Herniated disks affect more men than women.

Herniated disks may result from severe trauma or strain, or they may be related to intervertebral joint degeneration. In an elderly person with degenerative disk changes, minor trauma may cause herniation. A person with a congenitally small lumbar spinal canal or with osteophytes along the vertebrae may be more susceptible to nerve root compression with a herniated disk. This person is also more likely to exhibit neurologic symptoms.

How a herniated disk develops

How a herniated disk developsA spinal disk has two parts: the soft center called the nucleus pulposus and the tough, fibrous, surrounding ring called the anulus fibrosus. The nucleus pulposus acts as a shock absorber, distributing the mechanical stress applied to the spine when the body moves.

|

Physical stress—usually a twisting motion—can cause the anulus fibrosus to tear or rupture, allowing the nucleus pulposus to push through (herniate) into the spinal canal. This process allows the vertebrae to move closer together as the disk compresses. This, in turn, causes pressure on the nerve roots as they exit between the vertebrae. Pain and, possibly, sensory and motor loss follow.

A herniated disk can also occur with intervertebral joint degeneration. If the disk has begun to degenerate, minor trauma may cause herniation.

Herniation occurs in three stages: protrusion, extrusion, and sequestration.

Signs and symptoms

Vary according to location and extent of herniation.

Severe lower back pain to the buttocks, legs, and feet, usually unilaterally

Sudden pain after trauma, subsiding in a few days and then recurring at shorter intervals and with progressive intensity

Sciatic pain beginning as a dull pain in the buttocks

Sensory and motor loss in the area innervated by the compressed spinal nerve root and in later stages, weakness and atrophy of the leg muscles

Treatment

Unless neurologic impairment progresses rapidly, conservative initial treatment, consisting of bed rest (possibly with pelvic traction) for several days, supportive devices (such as a brace), heat or ice applications, and exercise or physical therapy

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroidal drugs such as dexamethasone (Decadron), or muscle relaxants such as diazepam (Valium) or methocarbamol (Robaxin), to reduce inflammation and edema at the injury site

Laminectomy and spinal fusion

Chemonucleolysis—injection of the enzyme chymopapain into the herniated disk to dissolve the nucleus pulposus: possible alternative to a laminectomy

Microdiscectomy to remove fragments of the nucleus pulposus

Analgesics

Weight reduction

Nursing considerations

Assess the patient’s pain. Give pain medications as ordered, and assess the patient’s response.

Offer supportive care, patient teaching, and encouragement to help the patient cope with the discomfort and frustration of back pain and impaired mobility. Include the patient and family members in all phases of his care.

Encourage the patient to verbalize his concerns about his disorder. Answer all of the patient’s questions.

Encourage the patient to perform as much self-care as his immobility and pain allow.

Help the patient identify and perform activities that promote rest and relaxation.

If the patient will undergo myelography, ask him about allergies to iodides, iodine-containing substances, or seafood because such allergies may indicate sensitivity to a radiopaque contrast agent used in the test. Monitor intake and output. Watch for seizures and an allergic reaction.

If the patient is in traction, make sure that the pelvic straps are properly positioned and that the weights are suspended. Periodically remove the traction to inspect the skin. Also remember to monitor the patient for deep vein thrombosis.

After laminectomy, microdiskectomy, or spinal fusion, enforce bed rest as ordered. If the patient has a blood drainage system (Hemovac) in place, check the tubing frequently for patency and a secure vacuum seal. Report colorless moisture on dressings (possible cerebrospinal fluid leakage) or excessive drainage immediately. Check the neurovascular status of the patient’s legs (color, motion, temperature, and sensation).

Monitor vital signs, and check for bowel sounds and abdominal distention. Use the logrolling technique to turn the patient. Administer analgesics as ordered, especially about 30 minutes before attempts to sit or walk.

Encourage participation in physical therapy.

Teaching about herniated disk

Teaching about herniated disk

Teach the patient about treatments, which may include bed rest and pelvic traction; heat application to the area to decrease pain; an exercise program; medications to decrease pain, inflammation, and muscle spasms; and surgery.

If weight reduction is indicated, teach the patient about appropriate dietary changes and refer him to a dietitian.

Before myelography, reinforce previous explanations of the need for this test, and tell the patient to expect some pain. Assure him that he’ll receive a sedative before the test, if needed, to keep him as calm and comfortable as possible. After the test, urge the patient to remain in bed with his head elevated (especially if metrizamide was used) and to drink plenty of fluids.

If surgery is required, explain all preoperative and postoperative procedures and treatments to the patient and his family.

Prepare the patient for discharge and encourage participation in prescribed physical therapy.

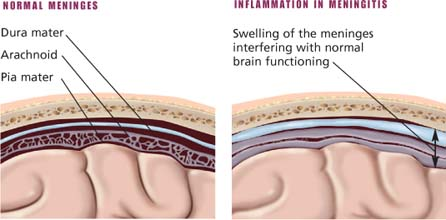

Meningitis

With meningitis, the brain and the spinal cord meninges become inflamed, usually as a result of a viral or a bacterial infection. Such inflammation may involve all three meningeal membranes—the dura mater, the arachnoid, and the pia mater. If the disease is recognized early and the infecting organism responds to antibiotics, the prognosis is good and complications are rare; however, mortality in untreated meningitis is 70% to 100%. The prognosis is worse for infants and the elderly, particularly if antibiotic therapy isn’t started within hours of symptom onset.

Meningitis is almost always a complication of another bacterial infection—bacteremia (especially from pneumonia, empyema, osteomyelitis, or endocarditis), sinusitis, otitis media, encephalitis, myelitis, or brain abscess—usually caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae (in children and young adults), or Streptococcus pneumoniae (in adults). In some cases, a virus is suspected. Meningitis may also follow skull fracture, a penetrating head wound, lumbar puncture, or ventricular shunting procedure. Aseptic meningitis may result from a virus or other organism. Sometimes, no causative organism can be found. Meningitis commonly begins as an inflammation of the pia-arachnoid, which may progress to congestion of adjacent tissues and destruction of some nerve cells.

Understanding aseptic viral meningitis

A benign syndrome, aseptic viral meningitis results from infection with enterovirus (most common), arbovirus, herpes simplex virus, mumps virus, or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.

Signs and symptoms usually begin suddenly with a temperature up to 104° F (40° C), drowsiness, confusion, stupor, and slight neck or spine stiffness when the patient bends forward. The patient history may reveal a recent illness.

Other signs and symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, poorly defined chest pain, and sore throat.

A complete patient history and knowledge of seasonal epidemics are key to differentiating among the many forms of aseptic viral meningitis. Negative bacteriologic cultures and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showing pleocytosis (increased number of cells in the CSF) and increased protein suggest the diagnosis. Isolation of the virus from CSF confirms it.

Treatment for aseptic viral meningitis includes bed rest, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, analgesics for pain, and exercises to combat residual weakness. Careful handling of excretions and good hand-washing technique prevent the spread of the disease.

Signs and symptoms

Fever

Chills

Malaise

Headache

Vomiting

Nuchal rigidity

Seizures

Positive Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s signs

Exaggerated and symmetrical deep tendon reflexes

Opisthotonos

Irritability, confusion

Sinus arrhythmias

Photophobia

Diplopia (and other visual problems)

Delirium

Deep stupor

Coma

Treatment

I.V. antibiotics (if bacterial)—for at least 2 weeks—followed by oral antibiotics

I.V. fluids

Mannitol to decrease cerebral edema

Anticonvulsants (usually given I.V.)

Sedative to reduce restlessness

Aspirin or acetaminophen (Tylenol) to relieve headache and fever

Bed rest

Isolation (if nasal cultures are positive)

Nursing considerations

Assess neurologic function often. Observe level of consciousness (LOC) and signs of increased intracranial pressure (plucking at the bedcovers, vomiting, seizures, and a change in motor function and vital signs). Watch for signs of cranial nerve involvement (ptosis, strabismus, and diplopia).

Be especially alert for a temperature increase up to 102° F (38.9° C), deteriorating LOC, onset of seizures, and altered respirations, all of which may signal an impending crisis.

Monitor fluid balance. Maintain adequate fluid intake to avoid dehydration, but avoid fluid overload because of the danger of cerebral edema. Measure central venous pressure and intake and output accurately.

Watch for adverse effects of I.V. antibiotics and other drugs.

Position the patient carefully to prevent joint stiffness and neck pain. Turn him often, according to a planned positioning schedule. Assist with range-of-motion exercises.

Maintain adequate nutrition and elimination.

Ensure the patient’s comfort. Provide mouth care regularly. Maintain a quiet environment.

Provide reassurance and support.

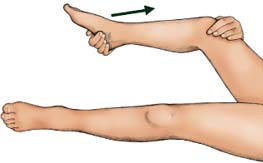

Important signs of meningitis

Important signs of meningitisA positive response to the following tests helps diagnose meningitis.

Brudzinski’s sign

Place the patient in a dorsal recumbent position; then put your hands behind his neck and bend it forward. Pain and resistance may indicate neck injury or arthritis. But if the patient also involuntarily flexes the hips and knees, chances are he has meningeal irritation and inflammation, a sign of meningitis.

|

Teaching about meningitis

Teaching about meningitis

Teach the patient and his family about meningitis and its signs and symptoms, including its effects on behavior. Reassure the family that the delirium and behavior changes caused by meningitis usually disappear.

Urge the patient to take drugs exactly as prescribed.

To help prevent meningitis, teach patients with chronic sinusitis or other chronic infections—as well as those exposed to people with meningitis—the importance of quick and proper medical treatment.

Encourage those in close contact with patient to receive prophylactic treatment.

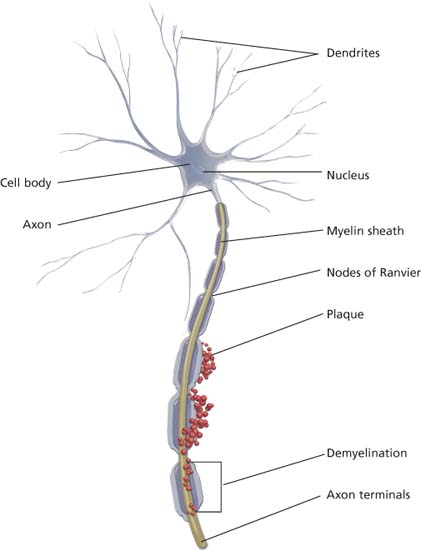

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive disease caused by demyelination of the white matter of the brain and spinal cord. With this disease, sporadic patches of demyelination throughout the central nervous system induce widely disseminated and varied neurologic dysfunction. Characterized by exacerbations and remissions, MS is a major cause of chronic disability in young adults.

Prognosis varies; MS may progress rapidly, disabling some patients by early adulthood or causing death within months of onset. However, 70% of patients lead active, productive lives with prolonged remissions.

The exact cause of MS is unknown, but current theories suggest a slow-acting or latent viral infection and an autoimmune response. Other theories suggest that environmental and genetic factors may also be linked to MS. Emotional stress, overwork, fatigue, pregnancy, and acute respiratory tract infections have been known to precede the onset of this illness.

Signs and symptoms

Vary with the extent and site of myelin destruction, the extent of remyelination, and the adequacy of subsequent restored synaptic transmission

May be transient or may last for hours or weeks; may wax and wane with no predictable pattern, vary from day to day, and be difficult for the patient to describe; may be so mild that the patient is unaware of them or so bizarre that he appears hysterical

Visual problems

Numbness

Tingling sensations (paresthesia)

Optic neuritis, diplopia, ophthalmoplegia, blurred vision, and nystagmus

Weakness, paralysis ranging from monoplegia to quadriplegia, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, and gait ataxia

Incontinence, frequency, urgency, and frequent infections

Mood swings, irritability, euphoria, and depression

Poorly articulated or scanning speech and dysphagia

Treatment

Immune-modulating therapy, with interferon or glatiramer acetate (Copaxone)

Steroids—used to reduce the associated edema of the myelin sheath during exacerbations

Baclofen (Lioresal), tizanidine (Zanaflex), or diazepam (Valium) to relieve spasticity

Cholinergic agents to relieve urine retention and minimize frequency and urgency

Amantadine (Symmetrel) or modafinil (Provigil) to relieve fatigue

Antidepressants

Comfort measures such as massages

Fatigue prevention

Pressure ulcer prevention

Bowel and bladder training (if necessary)

Antibiotics for bladder infections

Physical therapy

Counseling

Speech therapy

Occupational therapy

Planned exercise programs—help with maintaining muscle tone

Avoidance of extreme heat

Nursing considerations

Assist with physical therapy.

Assist with active, resistive, and stretching exercises to maintain muscle tone and joint mobility, decrease spasticity, improve coordination, and boost morale.

Evaluate the need for bowel and bladder training during hospitalization. Encourage adequate fluid intake and regular urination.

Promote emotional stability. Help the patient establish a daily routine to maintain optimal functioning. Encourage daily physical exercise and regular rest periods to prevent fatigue.

For more information, refer the patient to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Provide adequate nutrition and refer the patient to a nutritionist if appropriate.

Teaching about multiple sclerosis

Teaching about multiple sclerosis

Teach the patient and his family about the disease process, including its symptoms, complications, and treatments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Tissue changes in Alzheimer’s disease

Tissue changes in Alzheimer’s disease

Motor neuron changes in ALS

Motor neuron changes in ALS

Peripheral nerve demyelination

Peripheral nerve demyelination

Inflammation in meningitis

Inflammation in meningitis

Demyelination in multiple sclerosis

Demyelination in multiple sclerosis