Musculoskeletal care

Diseases

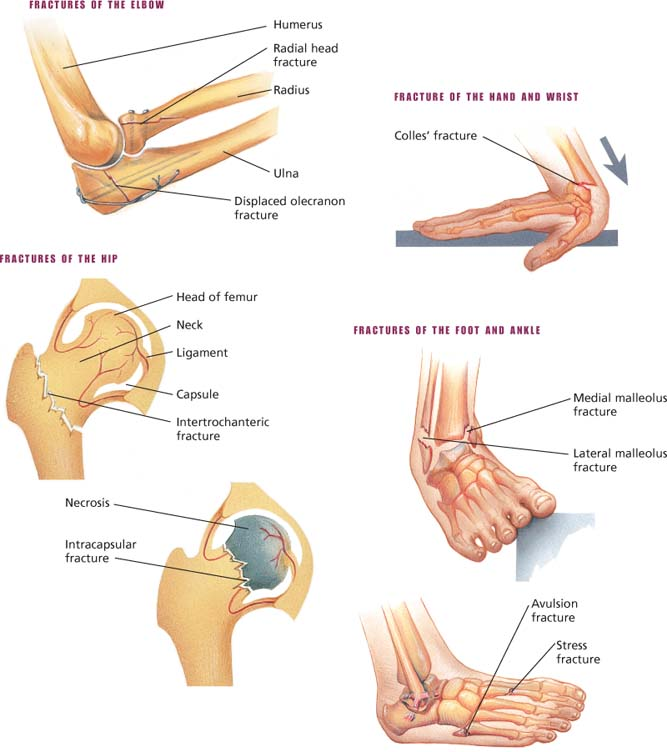

Arm and leg fractures

An arm or a leg fracture is a break in the continuity of the bone, usually caused by trauma. A fracture can result in substantial muscle, nerve, and other soft-tissue damage. The prognosis varies with the extent of disability or deformity, the amount of tissue and vascular damage, the adequacy of reduction and immobilization, and the patient’s age, health, and nutritional status. Children’s bones usually heal rapidly and without deformity; the bones of adults in poor health or those with osteoporosis or impaired circulation may never heal properly.

Most arm and leg fractures result from trauma, such as a fall on an outstretched arm, a skiing or motor vehicle accident, and child, spouse, or elder abuse (shown by multiple or repeated episodes of fractures). However, in a person with a bone-weakening disease, such as osteoporosis, bone tumor, or metabolic disease, a mere cough or sneeze can cause a pathological fracture. Prolonged standing, walking, or running can cause stress fractures of the foot and ankle—usually in nurses, postal workers, soldiers, and joggers.

Possible complications of fractures include arterial damage, nonunion, fat embolism, infection, shock, avascular necrosis, peripheral nerve damage, and compartment syndrome. Severe fractures, especially of the femoral shaft, may cause substantial blood loss and life-threatening hypovolemic shock.

Signs and symptoms

Crepitus

Deformity or shortening of the injured limb

Discoloration over the fracture site

Dislocation

Loss of pulses distal to the injury (arterial compromise)

Numbness distal to the injury and cool skin at the extremity’s end (nerve and vessel damage)

Pain that increases with movement and an inability to intentionally move part of the arm or leg distal to the injury

Soft-tissue edema

Skin wound and bleeding (open fracture)

Tingling sensation distal to the injury, possibly indicating nerve and vessel damage

Warmth at the injury site

Identifying peripheral nerve injuries

This table lists signs and symptoms that can help you pinpoint where a patient has nerve damage. Keep in mind that you won’t be able to rely on these signs and symptoms in a patient with severed extension tendons or severe muscle damage.

| Nerve | Associated injury | Sign or symptom |

|---|---|---|

| Radial | Fracture of the humerus (especially the middle and distal thirds) | The patient can’t extend his thumb. |

| Ulnar | Fracture of the medial humeral epicondyle | The patient can’t perceive pain in the tip of his little finger. |

| Median | Elbow dislocation or wrist or forearm injury | The patient can’t perceive pain in the tip of his index finger. |

| Peroneal | Tibia or fibula fracture or dislocation of the knee | The patient can’t extend his foot (this also may indicate sciatic nerve injury). |

| Sciatic and tibial | Rare with fractures or dislocations | The patient can’t perceive pain in his sole. |

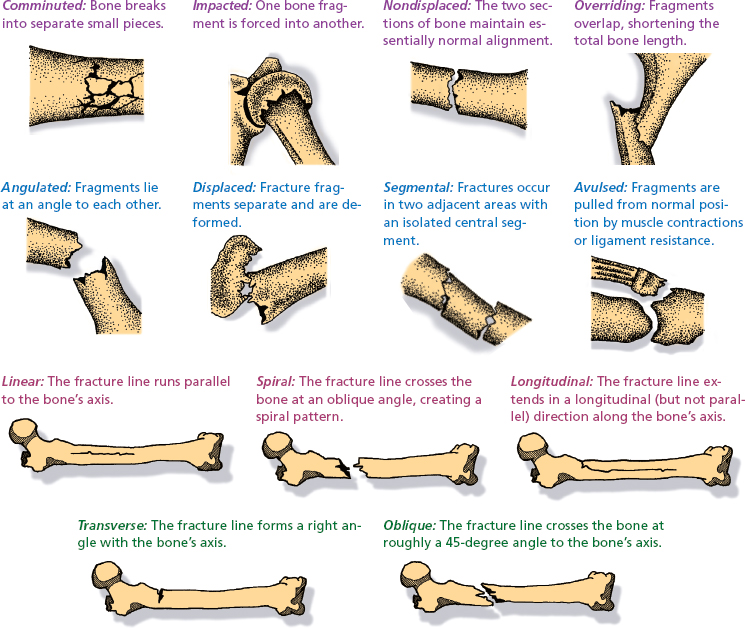

Classifying fractures

Classifying fracturesOne of the best-known systems for classifying fractures uses a combination of general terms to describe the fracture (for example, a simple, nondisplaced, oblique fracture).

Here are definitions of the classifications and terms used to describe fractures along with illustrations of fragment positions and fracture lines.

General classification of fractures

Simple (closed): Bone fragments don’t penetrate the skin.

Compound (open): Bone fragments penetrate the skin.

Incomplete (partial): Bone continuity isn’t completely interrupted.

Complete: Bone continuity is completely interrupted.

Treatment

Reduction of edema and pain by splinting the limb above and below the suspected fracture, applying a cold pack, and elevating the limb

Direct pressure to control bleeding (for severe fracture) to prevent blood loss

Fluid replacement (including blood products) to prevent or treat hypovolemic shock (for severe fracture)

Reduction (restoring displaced bone segments to their normal position) after confirmed fracture

Closed reduction (manual manipulation): a local anesthetic, such as lidocaine, and an analgesic, such as morphine I.M., to minimize pain; a muscle relaxant, such as diazepam I.V., or a sedative, such as midazolam, to facilitate muscle stretching that’s necessary for bone realignment

Open reduction: rods, plates, or screws placed during surgery to reduce and immobilize the fracture (if closed reduction isn’t possible); followed by casting

Immobilization: requires skin or skeletal traction, using a series of weights and pulleys (when the splint or cast fails to maintain reduction)

Careful wound cleaning, tetanus prophylaxis, prophylactic antibiotics and, possibly, additional surgery to repair soft-tissue damage (for an open fracture)

Nursing considerations

Know that the severity of pain depends on the fracture type.

Reassure the patient with a fracture, who will probably be frightened and in pain. Ease pain with analgesics as needed.

If the patient has a severe open fracture of a large bone, such as the femur, watch for signs of shock. Monitor his vital signs; a rapid pulse, decreased blood pressure, pallor, and cool, clammy skin may indicate shock. Administer I.V. fluids and blood products as ordered.

If the fracture requires long-term immobilization, reposition the patient often to increase comfort and prevent pressure ulcers. Assist with active range-of-motion exercises to prevent muscle atrophy. Encourage deep breathing and coughing to avoid hypostatic pneumonia.

In long-term immobilization, urge adequate fluid intake to prevent urinary stasis and constipation. Watch for signs of renal calculi (flank pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation).

Provide for diversional activity. Allow the patient to express his concerns over lengthy immobilization and the problems it creates.

Provide cast care. While the plaster cast is wet, support it with pillows. Observe for skin irritation near the cast edges, and check for foul odors or discharge, particularly after open reduction, compound fracture, or skin lacerations and wounds on the affected limb.

Encourage the patient to start moving around as soon as he can, and help him with walking.

After cast removal, refer the patient for physical therapy to restore limb mobility.

Know that arm and leg fractures may produce any or all of the “5 Ps”: pain and joint tenderness, pallor, pulse loss, paresthesia, and paralysis. The last three are distal to the fracture site.

Monitor the patient’s white blood cell count, hemoglobin level, and hematocrit, and report any abnormal values to the practitioner.

Be sure the patient with immobility from the fracture has adequate deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

Teaching about arm and leg fractures

Teaching about arm and leg fractures

Help the patient set realistic goals for recovery.

Show the patient how to use his crutches properly.

Tell the patient with a cast to report signs of impaired circulation (skin coldness, numbness, tingling, or discoloration) immediately. Warn him against getting the cast wet, and instruct him not to insert foreign objects under the cast.

Teach the patient to exercise joints above and below the cast as ordered.

Advise the patient not to walk on a leg cast or foot cast without the physician’s permission. If the patient has a fiberglass cast, he may be able to walk immediately. Plaster casts require 48 hours to dry and harden.

Emphasize the importance of returning for follow-up care.

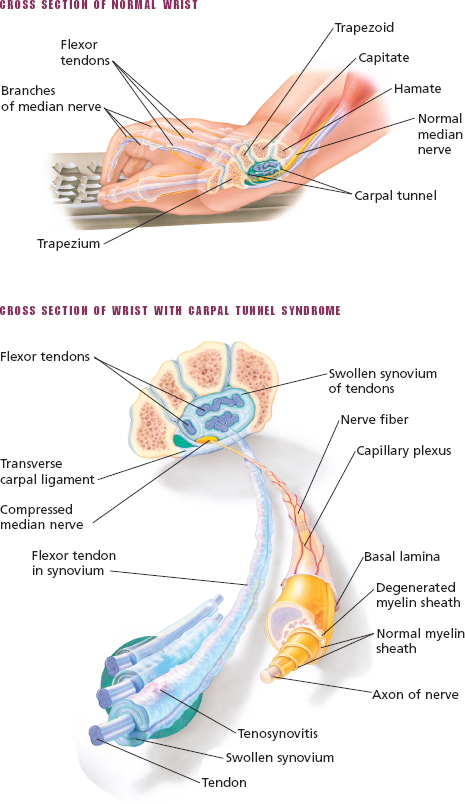

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome, a form of repetitive stress injury, is the most common nerve entrapment syndrome. It results from compression of the median nerve in the wrist, where it passes through the carpal tunnel.

The median nerve controls motions in the forearm, wrist, and hand, such as turning the wrist toward the body, flexing the index and middle fingers, and many thumb movements. It also supplies sensation to the index, middle, and ring fingers. Compression of this nerve causes loss of movement and sensation in the wrist, hand, and fingers.

Carpal tunnel syndrome usually occurs in women between ages 30 and 60 and may pose a serious occupational health problem. It may also occur in people who move their wrists continuously, such as butchers, computer operators, machine operators, and concert pianists. Any strenuous use of the hands—sustained grasping, twisting, or flexing—aggravates the condition.

Signs and symptoms

Fingernails that may be atrophied, with surrounding dry, shiny skin

Inability to make a fist

Pain, burning, numbness, or tingling in one or both hands

Pain relieved by shaking hands vigorously or dangling arms at the side

Pain that spreads to the forearm and, in severe cases, as far as the shoulder

Paresthesia that may affect the thumb, forefinger, middle finger, and half of the ring finger; worsening at night and in the morning

Weakness in the hand or wrist

Treatment

Wrist splinting for 1 to 2 weeks

Possible occupational changes

Correction of any underlying disorder

Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as indomethacin (Indocin), mefenamic acid (Ponstel), or naproxen

Injectable corticosteroids

Pyridoxine for vitamin B6 deficiency

Surgical decompression of the nerve by sectioning the entire transverse carpal tunnel ligament

Neurolysis (freeing the nerve fibers)

Nursing considerations

Encourage the patient to express his concerns. Listen and offer your support and encouragement.

Have him perform as much self-care as his immobility and pain allow. Provide him with adequate time to perform these activities at his own pace.

Administer mild analgesics as needed. Encourage the patient to use his hands as much as possible; if the condition has impaired his dominant hand, you may have to assist with eating and bathing.

After surgery, monitor vital signs and regularly check the color, sensation, and motion of the affected hand.

Be aware that the patient’s history may disclose that his occupation or hobby requires strenuous or repetitive use of the hands. It may also reveal a hormonal condition, wrist injury, rheumatoid arthritis, or another condition that causes swelling in carpal tunnel structures.

Testing for carpal tunnel syndrome

Testing for carpal tunnel syndromeTinel’s sign

Phalen’s maneuver

Teaching about carpal tunnel syndrome

Teaching about carpal tunnel syndrome

Teach the patient how to apply a splint. Advise him not to make it too tight. Show him how to remove the splint to perform gentle range-of-motion exercises (which should be done daily).

Advise the patient who’s about to be discharged to occasionally exercise his hands in warm water. If he’s using a sling, tell him to remove it several times a day to exercise his elbow and shoulder.

If the patient requires surgery, explain preoperative and postoperative care procedures.

Review the prescribed medication regimen. Emphasize that drug therapy may require 2 to 4 weeks before maximum effectiveness is achieved. If the regimen includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, advise taking the drug with food or antacids to decrease stomach upset. List possible adverse reactions. Instruct the patient regarding which adverse reactions require immediate medical attention.

If the patient is pregnant, advise her to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because of possible teratogenic effects.

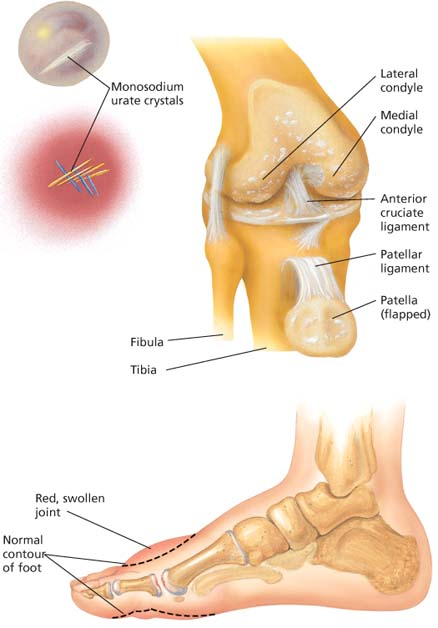

Gout

Gout—also known as gouty arthritis—is a metabolic disease marked by monosodium urate deposits that cause red, swollen, and acutely painful joints. Gout can affect any joint but mostly affects those in the feet, especially the great toe, ankle, and midfoot.

Primary gout typically occurs in men over age 30 and in postmenopausal women who take diuretics. It follows an intermittent course that may leave patients symptom-free for years between attacks. Secondary gout occurs in older people.

In asymptomatic patients, serum urate levels rise but produce no symptoms. In symptom-producing gout, the first acute attack strikes suddenly and peaks quickly. Although it may involve only one or a few joints, this attack causes extreme pain. Mild, acute attacks usually subside quickly yet tend to recur at irregular intervals. Severe attacks may persist for days or weeks.

Intercritical periods are the symptom-free intervals between attacks. Most patients have a second attack between 6 months and 2 years after the first; in some patients, the second attack is delayed for 5 to 10 years. Delayed attacks, which may be polyarticular, are more common in untreated patients. These attacks tend to last longer and produce more symptoms than initial episodes. A migratory attack strikes various joints and the Achilles tendon sequentially and may be associated with olecranon bursitis.

Secondary gout can be the result of other diseases such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, polycythemia, and sickle cell anemia.

Eventually, chronic polyarticular gout sets in. This final, unremitting stage of the disease (also known as tophaceous gout) is marked by persistent painful polyarthritis. An increased concentration of uric acid leads to urate deposits—called tophi—in cartilage, synovial membranes, tendons, and soft tissue. Tophi form in the fingers, hands, knees, feet, ulnar sides of the forearms, pinna of the ear, and Achilles tendon and, rarely, in such internal organs as the kidneys and myocardium. Renal involvement may adversely affect renal function.

Patients who receive treatment for gout have a good prognosis.

Signs and symptoms

Chills and a mild fever

Erosions, deformity, and disability

History of a sedentary lifestyle and hypertension and renal calculi

Pain in the great toe or another location in the foot

Pain that becomes so intense that eventually the patient can’t bear the weight of bed sheets or the vibrations of a person walking across the room

Skin over the tophi that ulcerates and releases a chalky white exudate or pus

Swollen, dusky red or purple joint with limited movement

Tophi, especially in the outer ears, hands, and feet

Warmth over the joint and extreme tenderness

Hypertension

Treatment

Correct management has three goals:

First, terminate the acute attack.

Next, treat hyperuricemia to reduce urine uric acid levels.

Finally, prevent recurrent gout and renal calculi.

Acute gout

Bed rest

Immobilization and protection of the inflamed, painful joints

Local application of cold

Analgesics such as acetaminophen (for mild attacks)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or I.M. corticotropin (for acute attacks)

Corticosteroids given orally or by intra-articular injection

Colchicine (Colcrys) (for acute attacks and for prophylaxis)

Understanding pseudogout

Pseudogout—also known as calcium pyrophosphate disease—results when calcium pyrophosphate crystals collect in periarticular joint structures.

Signs and symptoms

Like true gout, pseudogout causes sudden joint pain and swelling—most commonly of the knee, wrist, ankle, or other peripheral joints.

Pseudogout attacks are self-limiting and are triggered by stress, trauma, surgery, severe dieting, thiazide therapy, or alcohol abuse. Associated symptoms resemble those of rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of pseudogout involves joint aspiration and synovial biopsy to detect calcium pyrophosphate crystals. X-rays show calcium deposits in the fibrocartilage and linear markings along the bone ends. Blood tests may detect an underlying endocrine or metabolic disorder.

Treatment

Management of pseudogout may include aspirating the joint to relieve pressure; instilling corticosteroids and administering analgesics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat inflammation; and, if appropriate, treating the underlying disorder.

Without treatment, pseudogout leads to permanent joint damage in about half of those it affects, most of whom are elderly people.

Chronic gout

Decrease of serum uric acid level to less than 6.5 mg/dl

Allopurinol (Aloprim) (for overexcretion of uric acid)

Uricosuric agents (probenecid) that promote uric acid excretion and inhibit accumulation of uric acid

Colchicine, which prevents acute gout attacks but doesn’t affect uric acid levels

Avoidance of alcohol (especially beer and wine)

Limiting the use of purine-rich foods, such as anchovies, liver, sardines, kidneys, sweetbreads, and lentils

Weight loss program for obese patients (weight reduction decreases uric acid levels and eases stress on painful joints)

Surgery to improve joint function or correct deformities

Excision and drainage of infected or ulcerated tophi to prevent further ulceration, improve the patient’s appearance, or make it easier for him to wear shoes or gloves

Nursing considerations

To diffuse anxiety and promote coping mechanisms, encourage the patient to express his concerns about his condition. Listen supportively. Include him and family members in all phases of care and decision making. Answer questions about the disorder as completely as possible.

Urge the patient to perform as much self-care as his immobility and pain allow. Provide him with adequate time to perform these activities at his own pace.

Encourage bed rest, but use a bed cradle to keep bed linens off of sensitive, inflamed joints.

Carefully evaluate the patient’s condition after joint aspiration. Provide emotional support during diagnostic tests and procedures.

Give pain medication as needed, especially during acute attacks. Monitor the patient’s response to this medication. Apply cold packs to inflamed joints to ease discomfort and reduce swelling.

To promote sleep, administer pain medication at times that allow for maximum rest. Provide the patient with sleep aids, such as a bath, massage, or an extra pillow.

Help the patient identify techniques and activities that promote rest and relaxation. Encourage him to perform them.

Administer anti-inflammatory medication and other drugs as ordered. Watch for adverse reactions. Be alert for GI disturbances if the patient takes colchicine.

Encourage fluids, and record intake and output accurately. Be sure to monitor serum uric acid levels regularly. As ordered, administer sodium bicarbonate or other agents to alkalinize the patient’s urine.

Provide a nutritious diet without purine-rich foods.

Watch for acute gout attacks 24 to 96 hours after surgery. Even minor surgery can trigger an attack. Before and after surgery, administer colchicine to help prevent gout attacks, as ordered.

Teaching about gout

Teaching about gout

Urge the patient to drink plenty of fluids (up to 2 qt [2 L] per day) to prevent renal calculi.

Explain all treatments, tests, and procedures. Warn the patient before his first needle aspiration that it will be painful.

Make sure the patient understands the rationale for evaluating serum uric acid levels periodically.

Teach the patient relaxation techniques. Encourage him to perform them regularly.

Instruct the patient to avoid purine-rich foods, such as anchovies, liver, sardines, kidneys, and lentils, because these substances raise the urate level.

Discuss the principles of gradual weight reduction with the obese patient. Explain the advantages of a diet containing moderate amounts of protein and little fat.

If the patient receives allopurinol or other drugs, instruct him to report immediately any adverse reactions, such as nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, dizziness, urinary frequency, and dermatitis. Warn the patient taking probenecid or sulfinpyrazone to avoid aspirin or other salicylates. Their combined effect causes urate retention.

Inform the patient that long-term colchicine therapy is essential during the first 3 to 6 months of treatment with uricosuric drugs or allopurinol. Stress the importance of compliance.

Urge the patient to control hypertension, especially if tophaceous renal deposits are present. Keep in mind that diuretics aren’t advised for the patient with gout; alternative antihypertensives are preferred.

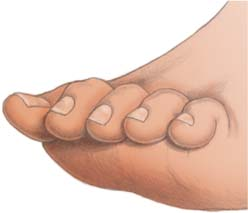

Hallux valgus

Hallux valgus is a common, painful foot condition that involves lateral deviation of the great toe at the metatarsophalangeal joint. It occurs with medial enlargement of the first metatarsal head and bunion formation (bursa and callus formation at the bony prominence). It’s more common in women.

With congenital hallux valgus, abnormal bony alignment (an increased space between the first and second metatarsal known as metatarsus primus varus) causes bunion formation. With acquired hallux valgus, bony alignment is normal at the outset of the disorder.

Signs and symptoms

A flat, splayed forefoot with severely curled toes (hammertoes)

Characteristic tender bunion covered by deformed, hard, erythematous skin and palpable bursa, typically distended with fluid

Chronic pain over a bunion

Family history of hallux valgus, degenerative arthritis, or both

Small bunion on the fifth metatarsal

Laterally deviated great toe

Pain over the second or third metatarsal heads

Treatment

Proper shoes and foot care to eliminate the need for further treatment

Felt pads to protect the bunion

Foam pads or other devices to separate the first and second toes at night

A supportive pad and exercises to strengthen the metatarsal arch

Bunionectomy

Warm compresses, soaks, exercises, and analgesics to relieve pain and stiffness

Nursing considerations

Encourage the patient to perform as much self-care as his immobility and pain allow. Give him time to perform these activities at his own pace.

Administer analgesics, as ordered, to relieve pain.

Before surgery, assess the foot’s neurovascular status (temperature, color, sensation, and blanching sign).

After bunionectomy, apply ice to reduce swelling. Increase negative venous pressure and reduce edema by elevating the foot or supporting it with pillows.

Record the neurovascular status of the patient’s toes, including the ability to move them (taking into account the inhibiting effect of the dressing). Perform this check every hour for the first 24 hours, then every 4 hours. Report any change in neurovascular status to the physician immediately.

Prepare the patient for walking by having him dangle his foot over the bedside briefly before he gets up. This increases venous pressure gradually.

Encourage the patient to express concerns about limited mobility, and offer support when appropriate. Answer any questions. Give positive reinforcement and, whenever possible, include the patient in care decisions.

Understanding hammertoe

Understanding hammertoeWith hammertoe, the toe assumes a clawlike position caused by hyperextension of the metatarsophalangeal joint, flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint, and hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal joint, usually under pressure from hallux valgus displacement.

Signs and symptoms

The combined pressure that causes hammertoe results in a painful corn on the back of the interphalangeal joint and on the bone end and a callus on the sole of the foot, both of which make walking painful. Hammertoe may be mild or severe and can affect one or all toes.

|

Diagnosis

Hammertoe can be congenital and familial or acquired from repeatedly wearing short, narrow shoes, which puts pressure on the end of the long toe. Acquired hammertoe is usually bilateral and commonly develops in children who rapidly outgrow their shoes and socks.

Treatment

In young children or adults with early deformity, repeated foot manipulation and splinting of the affected toe relieve discomfort and may correct the deformity. Other treatment includes protection of protruding joints with felt pads, corrective footwear (open-toed shoes and sandals or special shoes that conform to the shape of the foot), a metatarsal arch support, and exercises such as passive manual stretching of the proximal interphalangeal joint. Severe deformity requires surgical fusion of the proximal interphalangeal joint in a straight position.

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is an anteroposterior spinal curve that causes the back to bow, commonly at the thoracic level but sometimes at the thoracolumbar or sacral level. It was once known as “roundback” or “dowager’s hump.” The normal spine has a slightly convex shape, but excessive thoracic kyphosis is abnormal.

Kyphosis occurs in children and adults. Symptomatic adolescent kyphosis affects more girls than boys and is most common between ages 12 and 16.

Disk lesions (Schmorl’s nodes) may develop in this disorder. These small fingers of nuclear material (from the nucleus pulposus) protrude through the cartilage plates and into the spongy bone of the vertebral bodies. If the protrusion destroys the anterior portions of cartilage, bridges of new bone may form at the intervertebral space and cause ankylosis.

Teaching about hallux valgus

Teaching about hallux valgus

teach the patient how to use crutches if they are needed. Make sure the proper cast shoe or boot is used to protect the cast or dressing.

Before discharge, instruct the patient to limit activities, to rest frequently with feet elevated (especially with pain or edema), and to wear wide-toed shoes and sandals after the dressings are removed.

Teach the patient proper foot care, including cleanliness and massages. Show her how to cut toenails straight across to prevent ingrown nails and infection.

Demonstrate exercises the patient can do at home to strengthen foot muscles, such as standing at the edge of a step on the heel and then raising and inverting the top of the foot.

Stress the importance of follow-up care and prompt medical attention for painful bunions or corns.

If the patient needs surgery, explain all preoperative and postoperative procedures and treatments.

Signs and symptoms

A history of excessive athletic activity (in adolescents)

Compensatory lordosis

Fatigue, tenderness, or stiffness in the involved area or along the entire spine

Increased thoracic curvature when the patient stands or bends forward

Poor posture

Mild pain at the apex of the spinal curve

Treatment

Bed rest on a firm mattress (with or without traction) and a brace to correct the spinal curve until the patient stops growing

Pelvic tilt to decrease lumbar lordosis, hamstring stretch to overcome muscle contractures, and thoracic hyperextension to flatten the kyphotic curve

Spinal arthrodesis (rarely necessary unless kyphosis causes neurologic damage, a spinal curve greater than 60 degrees, or intractable and disabling back pain in a skeletally mature patient)

Posterior spinal fusion (with spinal instrumentation, iliac bone grafting, and plaster casting for immobilization) or an anterior spinal fusion (followed by casting) if kyphosis produces a spinal curve greater than 70 degrees

Nursing considerations

After surgery, check the patient’s neurovascular status every 2 to 4 hours for the first 48 hours and report any changes immediately. Turn the patient often, using the logroll method.

If patient-controlled analgesia isn’t used, offer an analgesic every 3 to 4 hours.

Maintain fluid balance and monitor for ileus.

Maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation.

Encourage family support. For an adolescent patient, suggest that family members supply diversional activities. For an adult patient, arrange for alternating periods of rest and activity.

If the patient requires a brace, check its condition daily. Look for worn or malfunctioning parts. Carefully assess how the brace fits the patient. Keep in mind that weight changes may alter proper fit.

Give meticulous skin care. Check the skin at the cast edges several times daily; use heel and elbow protectors to prevent skin breakdown. Remove antiembolism stockings, if ordered, at least three times per day for at least 30 minutes. Change dressings as ordered.

Provide emotional support and encourage communication. Urge the patient and family members to voice their concerns, and answer their questions completely. Expect more mood changes and depression in the adolescent patient than in the adult patient. Offer frequent encouragement and reassurance.

include the patient in care-related decisions. If possible, include family members in all phases of patient care.

Assist during suture removal and new cast application (usually about 10 days after surgery). Encourage gradual ambulation (usually beginning with a tilt table in the physical therapy department). As needed, arrange for follow-up care with a social worker and a home health nurse.

Teaching about kyphosis

Teaching about kyphosis

For the adolescent patient with kyphosis, outline the fundamentals of good posture and demonstrate prescribed exercises. Have the patient perform a return demonstration, if appropriate. Suggest bed rest to relieve severe pain. Encourage him to use a firm mattress, preferably with a bed board.

If the patient has a cast, provide detailed, written care instructions for the cast at discharge. Tell him to immediately report pain, burning, skin breakdown, loss of feeling, tingling, numbness, or cast odor. Urge him to drink plenty of liquids to avoid constipation and to report any illness (especially abdominal pain or vomiting) immediately. Show him how to use proper body mechanics to minimize strain on the spine. Warn him not to lie on his stomach or on his back with his legs flat.

If the patient is discharged with a brace, explain its purpose and tell him how and when to wear it. Make sure he understands how to check it daily for proper fit and function. Teach him to perform proper skin care. Advise against using lotions, ointments, or powders that can irritate the skin where it comes in contact with the brace. Warn that only the physician or orthotist should adjust the brace.

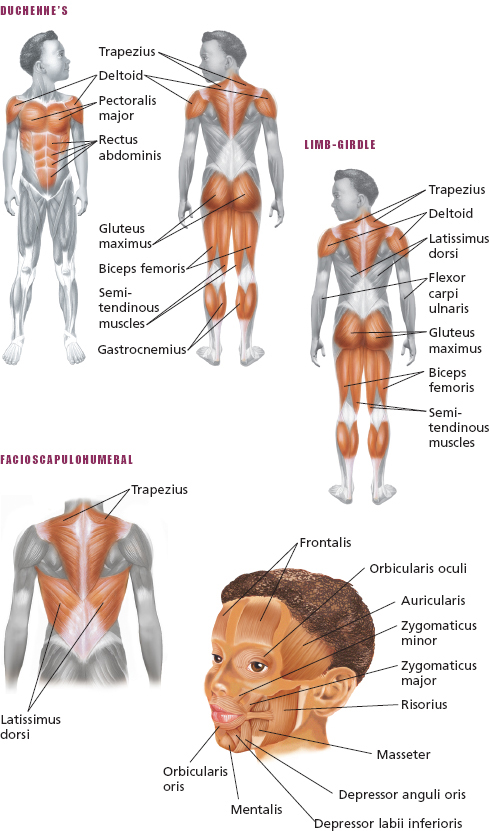

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy is a group of hereditary disorders characterized by progressive symmetrical wasting of skeletal muscles but no neural or sensory defects. Four main types of muscular dystrophy occur: Duchenne’s (pseudohypertrophic) muscular dystrophy, which accounts for 50% of all cases; Becker’s (benign pseudohypertrophic) muscular dystrophy; Landouzy-Dejerine (facioscapulohumeral) dystrophy; and Erb’s (limb-girdle) dystrophy. Duchenne’s and Becker’s muscular dystrophies affect males almost exclusively. The other two types affect both sexes about equally.

Depending on the type, the disorder may affect vital organs and lead to severe disability, even death. Early in the disease, muscle fibers necrotize and regenerate in various states. Over time, regeneration slows and degeneration dominates. Fat and connective tissue replace muscle fibers, causing weakness.

The prognosis varies. Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy typically begins during early childhood and causes death within 10 to 15 years. Patients with Becker’s muscular dystrophy may live into their 40s. Landouzy-Dejerine and Erb’s dystrophies usually don’t shorten life expectancy.

Signs and symptoms

Family history that points to evidence of genetic transmission

If another family member has muscular dystrophy, clinical characteristics that indicate the type of dystrophy and how he may be affected

Progressive muscle weakness that varies with the type of dystrophy

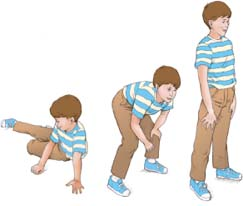

Testing for Gowers’ sign

Testing for Gowers’ sign |

A positive Gowers’ sign-an inability to lift the trunk without using the hands and arms to brace and push-indicates pelvic muscle weakness, as occurs in muscular dystrophy and spinal muscle atrophy. To check for Gowers’ sign, place the patient in the supine position and ask him to rise.

Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy

Begins insidiously

Gowers’ sign when rising from a sitting or supine position

Onset that typically occurs between ages 3 and 5

Rapid progression; by age 12, child usually unable to walk

Weakness that begins in the pelvic muscles and interferes with ability to run, climb, and walk

Wide stance and a waddling gait

Becker’s muscular dystrophy

Gowers’ sign

Resemble those of Duchenne’s but progress more slowly

Beginning after age 5, but patient can still walk well beyond age 15 and, in some cases, into his 40s

Wide stance and a waddling gait

Landouzy-Dejerine dystrophy

Abnormal facial movements

Absence of facial movements when laughing or crying

Diffuse facial flattening that leads to a masklike expression

Inability to pucker the lips or whistle

Inability to raise arms over the head or close eyes completely

Pelvic muscles weaken as the disease progresses

Pendulous lower lip

Symptoms that develop during adolescence

Nasolabial fold that disappears

Typically beginning before age 10

Weakness of the eye, face, and shoulder muscles

Inability to suckle (in infants)

Scapulae that develop a winglike appearance

Erb’s dystrophy

Slow course and commonly causes only slight disability

Inability to raise the arms

Lordosis with abdominal protrusion

Muscle weakness (first appears in the upper arm and pelvic muscles)

Muscle wasting

Onset between ages 6 and 10 but may occur in early adulthood

Poor balance

Waddling gait

Winging of the scapulae

Detecting muscular dystrophy

With muscular dystrophy, the trapezius muscle typically rises, creating a stepped appearance at the shoulder’s point.

|

From the posterior view, the scapulae ride over the lateral thoracic region, giving them a winged appearance. With Duchenne’s and Becker’s dystrophies, this winglike sign appears when the patient raises his arms. With other dystrophies, the sign is obvious without arm raising. (In fact, the patient can’t raise his arms.)

|

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Understanding common fractures

Understanding common fractures

Nerve compression in carpal tunnel syndrome

Nerve compression in carpal tunnel syndrome

Gout of the knee and foot

Gout of the knee and foot

Muscles affected in muscular dystrophy

Muscles affected in muscular dystrophy