Maternal and Fetal Health

INTRODUCTION TO MATERNITY NURSING

Providing care to childbearing families is aimed at the ideal of having every pregnancy result in a healthy mother, baby, and family unit. The nurse today faces many evolving and challenging issues in achieving this goal. Such advances as in vitro fertilization and embryo freezing have afforded people opportunities once thought impossible. An increasing number of high-risk pregnancies result from such factors as drug abuse, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, late or no prenatal care, teenage pregnancies, and pregnancies in women older than age 35.

Today’s childbearing families have many options. The planned birth may take place in the traditional hospital setting, a birthing center, or at home. The primary care provider may be a physician, a certified nurse-midwife, or a lay midwife. Birth-related choices commonly include the use of labor, delivery, and recovery rooms or labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum rooms; various birthing positions and analgesic methods; alternative pain-relief strategies such as hydrotherapy; and the decision to allow children and others to be present during labor and delivery. Regionalization of obstetric services has provided childbearing families with access to the technologic advances and skilled personnel capable of managing pregnancy or neonatal complications. The combination of advancing technology, pregnancy risk factors, and changing economics due to the rising cost of health care challenges the nurse to be a highly skilled clinician and outstanding communicator.

Terminology Used in Maternity Nursing

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseBond, L. (2011). Physiology of pregnancy. In S. Mattson & J. E. Smith (Eds.), Core curriculum for maternal-newborn nursing (4th ed., pp. 80-100). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Gestation—pregnancy or maternal condition of having a developing fetus in the body.

Embryo—human conceptus up to the 10th week of gestation (8th week postconception).

Fetus—human conceptus from 10th week of gestation (8th week postconception) until delivery.

Viability—capability of living, usually accepted as 24 weeks, although survival is rare.

Gravida (G)—woman who is or has been pregnant, regardless of pregnancy outcome.

Nulligravida—woman who is not now and never has been pregnant.

Primigravida—woman pregnant for the first time.

Multigravida—woman who has been pregnant more than once.

Para (P)—refers to past pregnancies that have reached viability.

Nullipara—woman who has never completed a pregnancy to the period of viability. The woman may or may not have experienced an abortion.

Primipara—woman who has completed one pregnancy to the period of viability regardless of the number of infants delivered and regardless of the infant being live or stillborn.

Multipara—woman who has completed two or more pregnancies to the stage of viability.

Living children—refers to the number of children a woman has delivered who are living.

A woman who is pregnant for the first time is a primigravida and is described as Gravida 1 Para 0 (or G1P0). A woman who delivered one fetus carried to the period of viability and who is pregnant again is described as Gravida 2, Para 1. A woman with two pregnancies ending in abortions and no viable children is Gravida 2, Para 0.

Obstetric History

TPAL

In some obstetric services, a woman’s obstetric history is summarized by a series of four digits, such as 5-0-2-5. These digits correspond with the abbreviation TPAL.

T—represents full-term deliveries, 37 completed weeks or more.

P—represents preterm deliveries, 20 to less than 37 completed weeks.

A—represents abortions, elective or spontaneous loss (miscarriage) of a pregnancy before the period of viability.

L—represents the number of children living. If a child has died, further explanation is needed for clarification.

If, for example, a particular woman’s history is summarized as G 7, P 5-0-2-5, then she has been pregnant seven times, had five term deliveries, zero preterm deliveries, two abortions, and five living children.

GTPALM

In some institutions a woman’s obstetric history can also be summarized as GTPALM, especially when multiple gestations or births are involved.

G—represents gravida.

T—represents full-term deliveries, 37 completed weeks or more.

P—represents preterm deliveries, 20 to less than 37 completed weeks.

A—represents abortions, elective or spontaneous loss of a pregnancy before the period of viability.

L—represents the number of children living. If a child has died, further explanation is needed for clarification.

M—represents the number of multiple gestations and births (not the number of neonates delivered).

If, for example, a particular woman’s history is summarized as G 5, P 5-0-0-6-1, then she has been pregnant five times, had five term deliveries, zero preterm deliveries, zero abortions, six living children, and one multiple gestation/birth.

THE EXPECTANT MOTHER

Manifestations of Pregnancy

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseBlackburn, S. T. (2008). Physiologic changes of pregnancy. In K. Rice-Simpson & P. A. Creehan (Eds.), AWHONN’s perinatal nursing (3rd ed., pp. 59-77). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Pregnancy may be determined by cessation of menses, enlargement of the uterus, and a positive result on a pregnancy test. These and the many other manifestations of pregnancy are classified into three groups: presumptive, probable, and positive.

Presumptive Signs and Symptoms

Physical signs and symptoms that suggest, but do not prove, pregnancy.

Abrupt cessation of menses—pregnancy is suspected if more than 10 days have elapsed since the time of the expected onset in a healthy woman who previously had predictable menstrual periods.

Breast changes:

Breasts enlarge and become tender. Veins in breasts become increasingly visible.

Nipples become larger and more pigmented. Nipple tingling may also be present.

Colostrum—a thin, milky fluid—may be expressed in the second half of pregnancy.

Montgomery glands—small elevations on the areolae— may appear.

Skin pigmentation changes:

Chloasma/melasma gravidarum (the mask of pregnancy)—brownish pigmentation appearing on the face in a butterfly pattern in 50% to 70% of women. It is usually symmetric and is distributed on the forehead, cheeks, and nose. The mask of pregnancy is more common in darkhaired, brown-eyed women and is progressive throughout the pregnancy.

Linea nigra—dark vertical line on the abdomen between the sternum and the symphysis pubis.

Abdominal striae (striae gravidarum)—reddish or purplish linear marks sometimes appearing on the breasts, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs because of the stretching, rupture, and atrophy of the deep connective tissue of the skin.

Nausea with or without vomiting (morning sickness)— occurs mainly in the morning but may occur at any time of the day, lasting a few hours. Begins between 2 and 6 weeks after conception and usually disappears spontaneously near the end of the first trimester (12 weeks).

Frequency of urination:

Caused by pressure of the expanding uterus on the bladder.

Decreases when the uterus rises out of the pelvis (around 12 weeks).

Reappears when the fetal head engages in the pelvis at the end of pregnancy.

Constipation—due to the decreased absorption of fluid by the gut.

Fatigue—characteristic of early pregnancy in response to increased hormonal levels.

Probable Signs and Symptoms

Objective findings detected by 12 to 16 weeks of gestation.

Enlargement of abdomen—at about 12 weeks’ gestation, the uterus can be felt through the abdominal wall, just above the symphysis pubis.

Changes in shape, size, and consistency of the uterus:

Uterus enlarges, elongates, and decreases in thickness as pregnancy progresses. The uterus changes from a pear shape to a globe shape.

Hegar’s sign—lower uterine segment softens 6 to 8 weeks after the onset of the last menstrual period.

Changes in cervix:

Chadwick’s sign—bluish or purplish discoloration of cervix and vaginal wall.

Goodell’s sign—softening of the cervix; may occur as early as 4 weeks.

With inflammation and carcinoma during pregnancy, the cervix may remain firm.

Intermittent contractions of the uterus (Braxton-Hicks contractions)—painless, palpable contractions occurring at irregular intervals, more frequently felt after 28 weeks. They usually disappear with walking or exercise.

Ballottement—sinking and rebounding of the fetus in its surrounding amniotic fluid in response to a sudden tap on the uterus (occurs near midpregnancy).

Changes in levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in maternal plasma and urine.

Leukorrhea—increase in vaginal discharge.

Quickening (sensations of fetal movement in the abdomen)—occurs between the 16th and 20th week after the onset of the last menses.

Positive hCG—laboratory (urine or serum) test for pregnancy.

Positive Signs and Symptoms

Diagnostic of Pregnancy

Fetal heart tones (FHTs)—usually heard between 16th and 20th week of gestation with a fetoscope or the 10th and 12th week of gestation with a Doppler stethoscope.

Fetal movements felt by the examiner (after about 20 weeks’ gestation).

Outlining of the fetal body through the maternal abdomen in the second half of pregnancy.

Sonographic evidence (after 4 weeks’ gestation) using vaginal ultrasound. Fetal cardiac motion can be detected by 6 weeks’ gestation.

Maternal Physiology During Pregnancy

Evidence Base

Evidence BaseBond, L. (2011). Physiology of pregnancy. In S. Mattson & J. E. Smith (Eds.), Core curriculum for maternal-newborn nursing (4th ed., pp. 80-100). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Duration of Pregnancy

Averages 280 days or 40 weeks (10 lunar months, 9 calendar months) from the first day of the last normal menses.

Duration may also be divided into three equal parts, or trimesters, of slightly more than 13 weeks or 3 calendar months each.

Estimated date of confinement (EDC), more commonly referred to now as estimated date of delivery (EDD), is calculated by adding 7 days to the date of the first day of the last menses and counting back 3 months (Nägele’s rule). Additionally, most antenatal clinics have obstetric wheels. These devices have an outer wheel that has markings for the calendar and an inner, sliding wheel with weeks and days of gestation. These wheels facilitate the estimation of gestational age (GA) and the calculation of the EDD. The quality of these wheels varies, but in general, the larger wheels yield better results.

For example, if a woman’s last menstrual period (LMP) began on September 10, 1999, her EDC would be June 17, 2000. The calculation would start with September 10, 1999, plus 7 days (September 17, 1999), minus 3 months (June 17, 1999). If the date of the woman’s LMP begins after March 31, an additional year must be added to give a correct EDD.

Another method of calculating the EDD is McDonald’s rule: after 24 weeks’ gestation, the fundal height measurement will correspond to the week of gestation plus 2 to 4 weeks.

EDD can also be calculated via ultrasound technology— the most accurate assessment—preferably in the first trimester. Gestational age in the first trimester is usually calculated from the fetal crown-rump length (CRL). This is the longest demonstrable length of the embryo or fetus, excluding the limbs and the yolk sac. The correlation between CRL and GA is excellent until about 12 weeks’ gestation and the estimate has a 95% confidence interval of plus or minus 6 days.

Changes in the Reproductive Tract

Uterus

Enlargement during pregnancy involves stretching and marked hypertrophy of existing muscle cells secondary to increased estrogen and progesterone levels.

In addition to an increase in the size of the uterine muscle cells, there is an increase in fibrous tissue and elastic tissue. The size and number of blood vessels and lymphatics increase.

Enlargement and thickening of the uterine wall are most marked in the fundus.

By the end of the third month (12 weeks), the uterus is too large to be contained wholly within the pelvic cavity—it can now be palpated suprapubically.

As the uterus rises out of the pelvis, it rotates somewhat to the right because of the presence of the rectosigmoid colon on the left side of the pelvis.

By 20 weeks’ gestation, the fundus has reached the level of the umbilicus.

By 36 weeks, the fundus has reached the xiphoid process.

By the end of the fifth month, the myometrium hypertrophy ends and the walls of the uterus become thinner, allowing palpation of the fetus.

During the last 3 weeks, the uterus descends slightly because of fetal descent into the pelvis.

Changes in contractility occur—from the first trimester, irregular painless contractions occur (Braxton-Hicks contractions). In the latter weeks of pregnancy, these contractions become stronger and more regular.

There is a progressive increase in uteroplacental blood flow during pregnancy.

Cervix

Pronounced softening and cyanosis—due to increased vascularity, edema, hypertrophy, and hyperplasia of the cervical glands.

Endocervical glands secrete thick mucus that forms a cervical plug and obstructs the cervical canal. This plug prevents bacteria and other substances from entering and ascending into the uterus.

Erosions of cervix, common during pregnancy, represent an extension of proliferating endocervical glands and columnar endocervical epithelium.

Evidence of Chadwick’s sign, the bluish, purplish coloring of the cervix. This sign is due to the increased vascularity and hyperemia caused by increased estrogen levels.

Ovaries

Ovulation ceases during pregnancy; maturation of new follicles is suspended.

One corpus luteum functions during early pregnancy (first 10 to 12 weeks), producing mainly progesterone. However, small levels of estrogen and relaxin are also produced by the corpus luteum.

After 8 weeks’ gestation, the corpus luteum remains the source for the hormone relaxin. However, relaxin is not required for a successful pregnancy outcome and normal delivery.

Vagina and Outlet

Increased vascularity, hyperemia, and softening of connective tissue in skin and muscles of the perineum and vulva.

Vaginal walls prepare for labor: mucosa increases in thickness, connective tissue loosens, and small-muscle cells hypertrophy. Secretions are thick, white, and acidic in nature and play a major role in the prevention of infections.

Vaginal secretions increase; pH is 3.5 to 6—because of increased production of lactic acid from glycogen in the vaginal epithelium by Lactobacillus acidophilus. (Acid pH probably aids in keeping vagina relatively free of pathogenic bacteria.)

Hypertrophy of the structures, along with fat deposits, causes the labia majora to close and cover the vaginal introitus (vaginal opening).

Changes in the Abdominal Wall

Striae gravidarum (stretch marks) may develop—reddish, slightly depressed streaks in the skin of abdomen, breast, and thighs (become glistening silvery lines after pregnancy).

Linea nigra may form—line of dark pigment extending from the umbilicus down the midline to the symphysis. Commonly during the first pregnancy, the linea nigra occurs at the height of the uterus. During subsequent pregnancies, the entire line may be present early in gestation.

Diastasis recti may occur as muscles (rectus) separate. If severe, a part of the anterior uterine wall may be covered by only a layer of skin, fascia, and peritoneum.

Breast Changes

Tenderness and tingling occur in early weeks of pregnancy.

Increase in size by second month—hypertrophy of mammary alveoli. Veins become more prominent and striae may develop as the breasts enlarge.

Nipples become larger, more deeply pigmented, and more erectile early in pregnancy.

Colostrum, a yellow secretion rich in antibodies, may be expressed by second trimester.

Areolae become broader and more deeply pigmented. The depth of pigmentation varies with the person’s complexion.

Scattered through the areola are a number of small elevations (glands of Montgomery), which are hypertrophic sebaceous glands.

Metabolic Changes

Numerous and intensive changes occur in response to rapidly growing fetus and placenta.

Weight Gain Average

Twenty-five to 35 pounds (11.5 to 16 kg) (see Table 36-1).

Table 36-1 Components of Weight Gain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Water Metabolism

The average woman retains 6 to 8 L of extra water during the pregnancy due to hormonal influence.

Approximately 4 to 6 L of fluid move into the extracellular spaces. This creates a physiologic increase in blood volume (hypervolemia).

Many pregnant women experience a normal accumulation of fluid in their legs and ankles at the end of the day. This is most common in the third trimester and is referred to as physiologic edema.

Sodium excretion in the normal pregnant woman is similar to the nonpregnant woman.

Sodium retention is usually directly proportional to the amount of water accumulated during the pregnancy. However, pregnancy lends itself toward sodium depletion, making sodium regulation more difficult.

Additional sodium is required during pregnancy to meet the need for increased intravascular and extracellular fluid volumes and to maintain a normal isotonic state.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTThe limitation of sodium is discouraged in pregnancy because it can result in decreased kidney function, resulting in decreased urine output. As a result, the pregnancy outcome could also be adversely affected.

Protein Metabolism

The fetus, uterus, and maternal blood are rich in protein rather than in fat or carbohydrates.

At term, fetus and placenta contain approximately 500 grams of protein or approximately half of the total protein increase of pregnancy.

Approximately 500 grams more of protein is added to the uterus, breasts, and maternal blood in the form of hemoglobin and plasma proteins.

Carbohydrate Metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy is controlled by glucose levels in the plasma and the metabolism of glucose in the cells.

The liver controls the plasma glucose level. Not only does it store glucose as glycogen, but it also converts it into glucose when the woman’s blood glucose levels are low.

Early in pregnancy, the effects of estrogen and progesterone can induce a state of hyperinsulinemia. As pregnancy advances, there is increased tissue resistance coupled with increased hyperinsulinemia.

Approximately 2% to 3% of all women will develop gestational diabetes mellitus during pregnancy regardless if they have a history of carbohydrate intolerance.

Pregnant women with preexisting diabetes mellitus (type 1 or 2) may experience a worsening of the disease attributed to hormonal changes occurring with pregnancy.

During pregnancy, there is a “sparing” of glucose used by maternal tissues and a shunting of glucose to the placenta for use by the fetus.

Human placental lactogen (placental hormone) promotes lipolysis, increases plasma-free fatty acids, and thereby provides alternative fuel sources for the mother.

Human placental lactogen, estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol oppose the action of insulin during pregnancy and promote maternal lipolysis as well.

Fat Metabolism

Lipid metabolism during pregnancy causes an accumulation of fat stores, mostly cholesterol, phospholipids, and triglycerides.

This accumulation of fat stores has no negligible effect on the fetus.

Fat storage occurs before the 30th week of gestation. After 30 weeks’ gestation, there is no further fat storage, only fat mobilization that correlates with the increased utilization of glucose and amino acids by the fetus.

The ratio of low-density proteins to high-density proteins is increased during pregnancy.

Nutrient Requirements

Caloric Requirements

Additional calories are usually not required during the first trimester due to the limited metabolic demands.

An additional 300 kcal/dL are required during the second and third trimester over the nonpregnant woman. However, due to the variety of women and their individualized needs, the exact caloric requirements need to be established on an individual basis.

Caloric expenditure varies throughout pregnancy. There is a slight increase in early pregnancy and a sharp increase near the end of the first trimester, continuing throughout pregnancy.

Protein Requirements

Protein is required for adequate amino acids to accommodate the normal development of the fetus, blood volume expansion, and growth of maternal breast and uterine tissue.

An additional requirement of 10 grams of protein per day is recommended over the nonpregnant intake.

Carbohydrate and Fat Requirements

As in the nonpregnant woman, carbohydrates should supply 55% to 60% of calories in the diet and should be in the form of complex carbohydrates, such as whole-grain cereal products, starchy vegetables, and legumes.

Fat intake should not exceed 30% of the diet. Saturated fats should not exceed 10% of the total calories.

Iron Requirements

Total circulating red blood cells (RBCs) increase about 20% to 30% (250 to 450 mL) during pregnancy; therefore, iron requirements are increased to 500 mg of iron needed: 270 mg by fetus; 90 mg by the placenta. This equates to 0.8 g/day in early pregnancy and 7.5 mg/day by term. This usually exceeds dietary intake.

Supplemental iron is valuable and necessary during pregnancy and for several weeks after pregnancy or lactation.

During the last half of pregnancy, iron is transferred to the fetus and stored in the fetal liver. This store lasts 3 to 6 months.

Changes in the Cardiovascular System

Heart

Diaphragm is progressively elevated during pregnancy; heart is displaced to the left and upward, with the apex moved laterally.

Heart sounds—exaggerated splitting of the first heart sound; a loud, easily heard third sound.

Heart murmurs—systolic murmurs are common and usually disappear after delivery.

Blood Volume Changes

Cardiac volume increases by 30% to 50% (1,450 to 1,750 mL), beginning as early as 6 weeks and peaking by 28 to 34 weeks’ gestation, causing slight hypertrophy of the heart and increased cardiac output. Women with multiple gestation can have higher cardiac outputs, especially after 20 weeks’ gestation.

Cardiac output increases by 30% to 50% above normal early in gestation with about one half of the increase occurring by 8 weeks’ gestation. It peaks in the second trimester and plateaus until term, reaching a volume of 6 to 7 L/minute by term.

Position greatly influences cardiac output, especially in the third trimester. In the supine position, the large uterus compresses the venous return from the lower half of the body to the heart. This may cause arterial hypotension, referred to as supine hypotensive syndrome. Cardiac output increases by 25% to 30%, with an increase in uterine and renal blood flow when the woman turns from her back to lateral position (either left or right side).

Femoral venous pressure increases—because of slowing of blood flow from lower extremities as a result of pressure of enlarged uterus on pelvic veins and inferior vena cava.

Increased cutaneous blood flow dissipates excess heat caused by increased metabolism of pregnancy.

Plasma volume increases 40% to 60% (1,200 to 1,600 mL) by term, resulting in hemodilution, more commonly referred to as physiologic anemia of pregnancy or physiologic dilutional anemia. This “anemic” state is not a true pathologic state and does decrease the risk of thrombosis. It is due to the rapid increase in plasma volume and the later increase in RBC volume.

Blood Pressure Changes

Blood pressure (BP)—during the first half of pregnancy, there is a slight (5 to 10 mm Hg) decrease in systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP), with the lowest point occurring in the second trimester. By the third trimester, the BP gradually returns to prepregnancy levels.

Maternal position influences BP: the highest reading is obtained in the sitting position, the lowest reading is obtained in the left lateral position, and an intermediate reading is obtained in the supine position. Sitting or standing positions show minimal change in SBP readings; however, can decrease the DBP by about 10 to 15 mm Hg.

Maternal BP will also rise with uterine contractions and returns to the baseline level after the uterine contraction is over.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTHypertensive disease affects up to 22% of pregnancies and is associated with maternal and fetal death. According to the National Institutes of Health, women with hypertension in pregnancy should be referred to as having hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Additionally the term “gestational hypertension” replaces the term “pregnancy-induced hypertension” to describe cases in which elevated BP without proteinuria occurs in a woman past 20 weeks of gestation who previously had a normal BP. Essentially, gestational hypertension is an elevated BP past 20 weeks of gestation without proteinuria.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTEnsure that the maternal BP is not taken during uterine contractions because it may give you a false elevated BP. Blood pressure readings should be measured in the same extremity, with the woman in the same position. BP should be measured with the BP cuff at the level of the woman’s heart, regardless of the position (sitting, standing, or lateral). This may mean that the BP is taken on the dependent arm (the arm the patient is lying on). If this occurs, move the dependent arm out from underneath the patient’s side to ensure unobstructed vessels and take BP.

Hematologic Changes

Total volume of circulating RBCs increases 17% to 33%; hemoglobin concentration at term averages 12 to 16 g/dL; hematocrit concentration at term averages 37% to 47%.

Average leukocyte (white blood cell [WBC]) count in the third trimester is 5 to 12,000/mm3. WBC count can be elevated as high as 30,000 or more during labor—cause unknown; probably represents the reappearance in the circulation of leukocytes previously shunted out of active circulation.

Pregnancy is a hypercoagulable state due to the increased levels of a number of essential coagulation factors. These factors include factor I (fibrinogen by 50%), factor V (proaccelerin or labile factor), factor VII (proconvertin or serum prothrombin conversion accelerator), factor VIII (antihemophilic factor or antihemophilic globulin), factor IX (plasma thromboplastin component or Christmas factor), factor X (Stuart or Prower factor), factor XII (Hageman or glass or contact factor) and vWF (von Willebrand factor antigen). Factor II (prothrombin) increases slightly, whereas factors XI (plasma thromboplastin antecedent) and XIII (fibrin-stabilizing factor) decrease during pregnancy.

There is no significant change in the number, appearance, or function of platelets. Average platelet count is 150,000 to 400,000/mm3, which increases the risk to the pregnant woman for venous thrombosis.

Changes in the Respiratory Tract

Diaphragm is elevated (about 4 cm) during pregnancy—chiefly by the enlarging uterus that decreases the length of the lungs.

Thoracic cage expands its anteroposterior diameter (by 2 cm). The increased pressure from the uterus also widens the substernal angle by about 50%, causing slight flaring of the ribs—result of increased mobility of rib attachments.

Breathing is more diaphragmatic than costal.

Total lung volume (amount of air in lungs at maximum inspiration) decreases by about 5%. Residual volume (amount of air in lungs after maximum expiration), respiratory reserve volume (max amount of air expired during rest), and functional residual capacity (amount of air remaining in lungs at rest and allowing for gas exchange) drop by about 18% to 20%.

Hyperventilation occurs—that is, an increase in respiratory rate, tidal volume (amount of air inspired and expired with normal breath) increases by 30% to 40%, and minute ventilation (amount of air inspired in 1 minute) increases by 40%.

Increased total volume lowers partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (Paco2), causing mild respiratory alkalosis that is compensated for by lowering of the bicarbonate concentration.

Increased respiratory rate and reduced Paco2 are probably induced by progesterone and estrogen to a lesser degree on the respiratory center.

Oxygen consumption increases 15% to 20% and as much as 300% in labor. This increase leads to increased maternal alveolar and arterial oxygen partial pressure levels.

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) elevates to 106 to 108 mm Hg in first trimester and 101 to 104 mm Hg at term. Paco2 is decreased to 27 to 32 mm Hg. Bicarbonate decreases to 18 to 21 mEq/L. Normal pH during pregnancy is 7.40 to 7.45. These changes allow for removal of fetal carbon dioxide via passive diffusion in the placenta.

Approximately 60% to 70% of pregnant women experience shortness of breath; the cause is unknown.

Nasal stuffiness and epistaxis (nosebleeds) are also common during pregnancy, secondary to vascular congestion caused from the increased estrogen levels.

Net effect of all changes in lung volume = no change in maternal maximum breathing capacity during pregnancy.

Changes in Renal System

Ureters become dilated and elongated during pregnancy because of mechanical pressure and perhaps due to the effects of progesterone. When the uterus rises out of the uterine cavity, it rests on the ureters, compressing them at the pelvic brim. Dilation is greater on the right side—the left side is cushioned by the sigmoid colon.

Renal plasma flow (RPF) increases by 60% to 80% by the end of the first trimester due to the increases in blood volume and cardiac output and the decreases in the systemic vascular resistance (all due to the effects of progesterone).

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) increases 40% to 50% by the second trimester, and the increase persists almost to term. RPF increases early in pregnancy and decreases to nonpregnant levels in the third trimester. These changes may be due to placental lactogen.

Glucosuria may be evident because of the increase in glomerular filtration without an increase in tubular resorptive capacity for filtered glucose.

Excreted protein may be increased due to the increased GFR, but is not considered abnormal until the level exceeds 250 mg/dL. Slight amounts of protein may be excreted during or just after vigorous labor.

Toward the end of pregnancy, pressure of the presenting part impedes drainage of blood and lymph from the bladder base, typically leaving the area edematous, easily traumatized, and more susceptible to infection.

Due to the increased RPF and GFR, the amount of glucose the kidneys filter increases 10- to 100-fold. The kidneys cannot always keep up with this increase; therefore, whatever glucose that is not filtered is lost in the urine, contributing to glycosuria.

Protein excretion is also increased to a rate not always handled by the kidneys’ tubular reabsorptive capability. Therefore, protein can spill into the urine. However, protein in the urine should not be considered an abnormal finding until 24-hour urine values exceed 300 mg/dL.

Changes in GI Tract

Gums may become hyperemic and softened and may bleed easily.

A localized vascular swelling of the gums may appear—called epulis of pregnancy.

Stomach and intestines are displaced upward and laterally by the enlarging uterus. Heartburn (pyrosis) is common, caused by reflux of acid secretions in the lower esophagus.

Tone and motility of GI tract decrease, leading to prolongation of gastric emptying due to the large amount of progesterone produced by the placenta. Decreased motility, mechanical obstruction by the fetus, and decreased water absorption from the colon leads to constipation.

Hemorrhoids are common because of elevated pressure in veins below the level of the large uterus and constipation.

Distention and hypotonia of the gallbladder are common, which can cause stasis of bile. Additionally, there is a decrease in emptying time and thickening of bile, resulting in hypercholesterolemia and gallstone formation.

Liver function tests are altered. With pregnancy, bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase values are unchanged; prothrombin time may show a slight increase or be unchanged. Liver size and morphology are unchanged.

Peptic ulcer formation or exacerbation is uncommon during pregnancy due to decreased hydrochloric acid (caused by increased estrogen levels).

The appendix is pushed superiorly.

Changes in the Endocrine System

Anterior pituitary gland enlarges in both weight (30% increase) and volume (two-fold increase). Its shape also changes from convex to dome-shaped; posterior pituitary gland remains unchanged.

Thyroid is moderately enlarged because of hyperplasia of glandular tissue and increased vascularity.

Basal metabolic rate increases progressively during normal pregnancy (as much as 25%) because of metabolic activity of fetus.

Level of protein-bound iodine and thyroxine rises sharply and is maintained until after delivery because of increased circulatory estrogen and hCG.

Hyperthyroidism during pregnancy is rare. Although levels of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are elevated by as much as 40% to 100% by term, this is a result of estrogen, hCG, and increased urinary iodide secretion, resulting in “euthyroid hyperthyroxinemia.”

Parathyroid gland size is known to increase, but there is a decrease in the parathyroid hormone (PTH) during pregnancy. This decrease is balanced by the fetus’ and the placenta’s increased production of PTH.

Adrenal secretions considerably increased—amounts of aldosterone increase as early as the 15th week to accommodate for the increased sodium excretion.

Pancreas—because of the fetal glucose needs for fetal growth, there are alterations in maternal insulin production and usage.

Estrogen, progesterone, cortisol, and human placental lactogen (hPL) decrease the maternal utilization of glucose.

Cortisol also increases maternal insulin production.

Insulinase, an enzyme produced by the placenta, deactivates maternal insulin.

These changes result in an increased need for insulin, and the islets of Langerhans increase their production of insulin.

Changes in Integumentary System

Pigment changes occur because of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (due to increased estrogen and progesterone), the level of which is elevated from the second month of pregnancy until term.

Striae gravidarum appear in later months of pregnancy as reddish, slightly depressed streaks in the skin of the abdomen and occasionally over the breasts and thighs and occur in as much at 50% of all pregnant women.

A brownish-black line of pigment is usually formed in the midline of the abdominal skin—known as linea nigra.

Brownish patches of pigment may form on the face—known as chloasma/melasma or “mask of pregnancy.” Chloasma usually disappears after pregnancy, but can reappear with excessive exposure to the sun or with oral contraceptive treatment.

Angiomas (vascular spider nevis)—minute red elevations commonly on the skin of the face, neck, upper chest, legs, and arms—may develop.

Reddening of the palms (palmar erythema) may also occur.

There is also an increased warmth to the skin and increased nail growth.

Changes in the Musculoskeletal System

The increasing mobility of sacroiliac, sacrococcygeal, and pelvic joints during pregnancy is a result of hormonal changes, specifically the hormone relaxin.

The center of gravity shifts secondary to increased weight gain, fluid retention, lordosis, and mobile ligaments. This mobility and the change in the center of gravity contribute to alteration of maternal posture and to back pain.

Late in pregnancy, aching, numbness, and weakness in the upper extremities may occur because of lordosis and paresthesia, which ultimately produces traction on the ulnar and median nerves.

Separation of the rectus muscles due to pressure of the growing uterus creates what is called a diastasis recti. If this is severe, a portion of the anterior uterine wall is covered by only a layer of skin, fascia, and peritoneum.

Changes in the Neurologic System

Usually no system changes.

Mild frontal headaches are common in the first and second trimester and are usually related to tension or hormonal changes.

Dizziness is common and is related to vasomotor instability, postural hypotension, or hypoglycemia following long periods of standing or sitting.

Tingling sensations in the hands are common and are due to excessive hyperventilation, which decreases maternal Paco2 levels.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERTSevere headaches that occur after 20 weeks’ gestation and are accompanied by visual changes, elevated BP (systolic >140 mm Hg or diastolic >90 mm Hg), and proteinuria should be evaluated immediately.

Changes in Hormonal Responses

Steroid Hormones

Estrogen:

Is secreted by the ovaries in early pregnancy, but by 7 weeks’ gestation, over half of the estrogen is secreted by the placenta.

The three classic estrogens during pregnancy are estrone, estradiol, and estriol. More than 90% of the estrogen secreted during pregnancy is estriol.

Estrogens also ensure uterine growth and development, maintenance of uterine elasticity and contractility, maintenance of breast growth and its ductal structures, and enlargement of the external genitalia.

Progesterone:

Is initially secreted by the corpus luteum and later by the placenta.

Plays a critical role in the maintenance of the pregnancy by suppressing the maternal immunologic response to the fetus and the rejection of the trophoblasts.

Progesterone also helps to maintain the endometrium, inhibits uterine contractility, helps in the development of breast lobules for lactation, stimulates the maternal respiratory center, and relaxes smooth muscle.

Placental Protein Hormones

hCG:

Secreted by the syncytiotrophoblasts and stimulates the production by the corpus luteum of progesterone and estrogen until the fully developed placenta takes over.

In multiple gestations, hCG can be twice as high as in a single pregnancy.

hCG levels peak around 10 weeks’ gestation (50,000 to 100,000 mIU/mL) then decrease to 10,000 to 20,000 mIU/mL by 20 weeks’ gestation.

hPL:

Also referred to as human chorionic somatomammotropin. Produced by the syncytiotrophoblasts of the placenta; detected in maternal serum as early as 6 weeks’ gestation.

Serum hPL levels rise concomitantly with placental growth.

hPL is an antagonist of insulin. It increases the amount of free fatty acids available to the fetus for metabolic needs and decreases the maternal metabolism of glucose allowing for protein synthesis. This action allows the fetus to have the needed nutrients when the woman is not eating.

Other Hormones

Prostaglandins:

Exact function is still unknown.

Affect smooth muscle contractility and some potent vasodilators.

Essential for the cardiovascular adaptation to pregnancy, cervical ripening, and initiation of labor.

Increased levels of prostaglandins may lead to vasodilation.

Relaxin:

Secreted primarily by the corpus luteum. Can be secreted in small amounts by the decidua and the placenta.

Inhibits uterine activity, decreases the strength of uterine contractions, softens the cervix, and remodels collagen.

Prolactin:

Released from the anterior pituitary gland.

Responsible for sustaining milk protein, casein, fatty acids, lactose, and the volume of milk secretion during lactation.

Structure of the Pelvis

Bones of the Pelvis

The pelvis is composed of four bones:

Two innominate bones (hip bones) form the sides and front.

Sacrum and coccyx form the back. Pelvic bones are held together by fibrocartilage of the symphysis pubis and several ligaments.

Divisions of the Pelvis

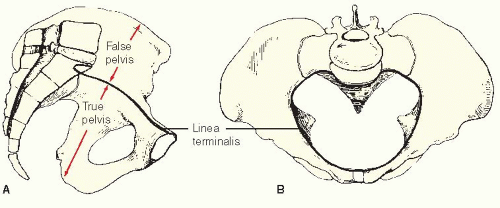

False pelvis—lies above an imaginary line called the linea terminalis or pelvic brim (see Figure 36-1). Function of the false pelvis is to support the enlarged uterus.

True pelvis lies below the pelvic brim or linea terminalis; it is the bony canal through which the fetus must pass. It is divided into three planes: the inlet, the midpelvis, and the outlet.

Inlet:

Upper boundary of the true pelvis—bounded by upper margin of symphysis pubis in front, linea terminalis on sides, and sacral promontory (first sacral vertebra) in back.

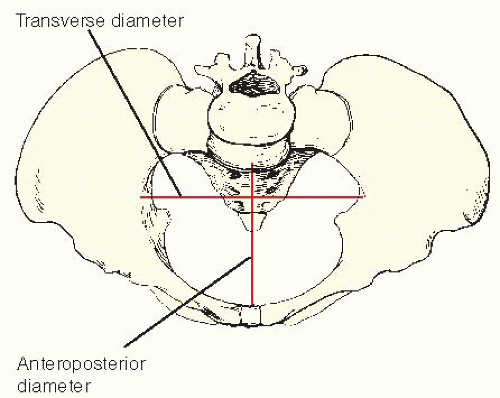

Largest diameter of inlet is transverse (see Figure 36-2).

Smallest diameter of inlet is anteroposterior.

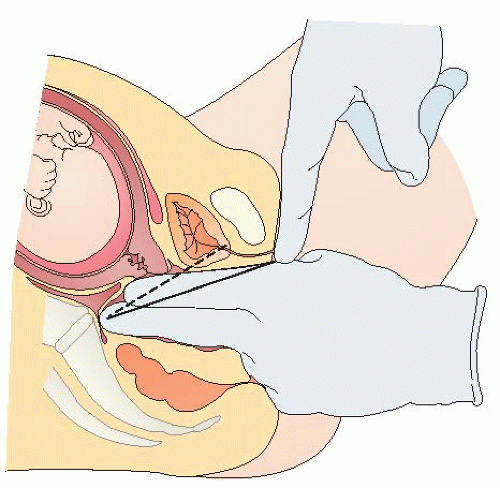

Anteroposterior diameter is most important diameter of inlet: measured clinically by diagonal conjugate— distance from lower margin of symphysis to the sacral promontory (usually 5½ inches [14 cm]) (see Figure 36-3).

Obstetric (true) conjugate—distance between inner surface of symphysis and sacral promontory measured by subtracting½ to¾ inch (1.5 to 2 cm) (thickness of symphysis) from the diagonal conjugate. Adequate diameter is usually 4½ inches (11.5 cm). This is the shortest anteroposterior diameter through which the fetus must pass.

Midpelvis:

Bounded by inlet above and outlet below—true bony cavity. Midpelvis contains the narrowest portion of the pelvis.

Diameters cannot be measured clinically.

Clinical evaluation of adequacy is made by noting the ischial spines. Prominent spines that protrude into the cavity indicate a contracted midpelvic space. The interspinous diameter is 4 inches (10 cm).

Outlet:

Lowest boundary of the true pelvis.

Bounded by lower margin of symphysis in front, ischial tuberosities on sides, tip of sacrum posteriorly.

Most important diameter clinically is distance between the tuberosities (>4 inches).

Shapes of the Pelvis

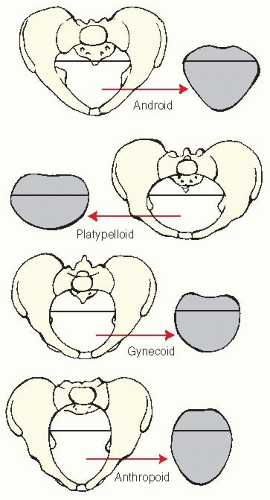

There are four main types of pelvic shapes (see Figure 36-4).

Gynecoid (normal female pelvis); optimal diameters in all three planes; 50% of all women.

Android (normal male pelvis); posterior segments are decreased in all three planes; deep transverse arrest of descent of the fetus and failure of rotation of the fetus are common; 20% of all women.

Anthropoid (apelike pelvis with long anteroposterior diameter); may allow for easy delivery of an occiput-posterior presentation of the fetus; 25% of all women.

Platypelloid (flat female pelvis with wide transverse diameter); arrest of fetal descent at the pelvic inlet is common; labor progress can be poor; 5% of all women.

Figure 36-3. Measurement of diagonal conjugate diameter. Straight line shows diagonal conjugate; dotted line shows true conjugate. |

Figure 36-4. The four types of female pelvises. Android— male-type pelvis. Platypelloid—broad pelvis with shortened anteroposterior diameter and flattened, oval, transverse shape. Gynecoid—typical female pelvis in which inlet is round instead of oval. Anthropoid—pelvis in which anteroposterior diameter is equal to or greater than the transverse diameter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|