Male reproductive care

Diseases

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

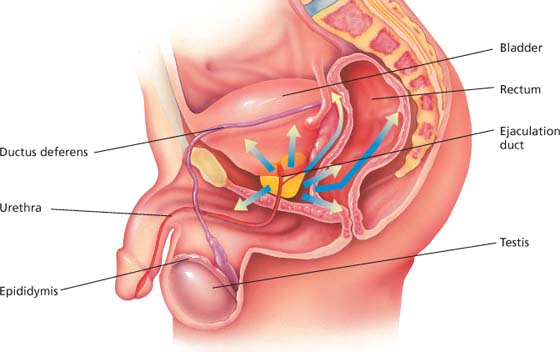

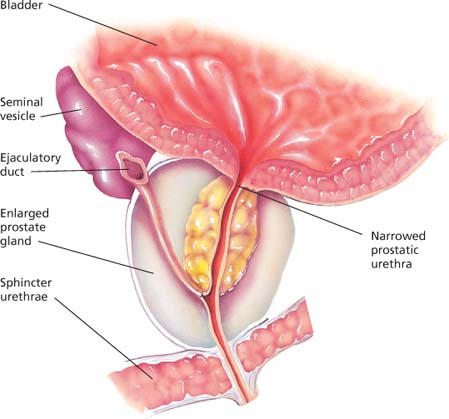

In benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) the prostate gland enlarges sufficiently to compress the urethra and cause some overt urinary obstruction. BPH begins with changes in periurethral glandular tissue. As the prostate enlarges, it may extend into the bladder and obstruct urine outflow by compressing or distorting the prostatic urethra. BPH may also cause a diverticulum musculature that retains urine when the rest of the bladder empties.

Recent evidence suggests a link between BPH and hormonal activity. As men age, production of androgenic hormones decreases, causing an imbalance in androgen and estrogen levels and high levels of dihydrotestosterone, the main prostatic intracellular androgen. Other theoretical causes include neoplasm, arteriosclerosis, inflammation, and metabolic or nutritional disturbances.

Signs and symptoms

Clinical features of BPH depend on the extent of prostatic enlargement and on the lobes affected:

Prostatism (decreased urine stream caliber and force)

Interrupted stream

Urinary hesitancy

Difficulty starting urination

Feeling of incomplete voiding

Frequent urination

Nocturia

Dribbling

Urine retention

Incontinence

Possibly hematuria

Visible midline mass above the symphysis pubis (incompletely emptied bladder)

Treatment

Prostatic massages, sitz baths, shortterm fluid restriction (to prevent bladder distention), and antimicrobials (for infection)

Regular sexual activity (for relief of prostatic congestion)

Terazosin (Hytrin), finasteride (Propecia), and tamsulosin (Flomax)

Transurethral resection (for a prostate weighing less than 2 oz [57 g]), vaporization of the prostate, or a prostate incision with a scalpel or laser

Suprapubic (transvesical) prostatectomy (when prostatic enlargement remains within the bladder area)

Perineal prostatectomy (for a large gland in an older patient), commonly resulting in impotence and incontinence

Retropubic (extravesical) prostatectomy (allows direct visualization); potency and continence usually maintained

Transurethral microwaves (heat therapy); their efficacy lies between that of an alpha-adrenergic blocker and surgery

Nursing considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests and surgery as appropriate.

Monitor and record the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, and daily weight. Watch closely for signs of postobstructive diuresis (such as increased urine output and hypotension), which may lead to dehydration, lowered blood volume, shock, electrolyte losses, and anuria.

Administer antibiotics as ordered for urinary tract infection, urethral procedures that involve instruments, and cystoscopy.

If urine retention occurs, try to insert an indwelling urinary catheter. If the catheter can’t be passed transurethrally, assist with suprapubic cystostomy. Watch for rapid bladder decompression.

Avoid giving a patient with BPH decongestants, tranquilizers, alcohol, antidepressants, or anticholinergics because these drugs can worsen the obstruction.

After prostatic surgery

Maintain the patient’s comfort, and watch for and prevent postoperative complications. Observe for signs of shock and hemorrhage. Check the catheter frequently (every 15 minutes for the first 2 to 3 hours) for patency and urine color; check the dressings for bleeding.

Postoperatively, many urologists insert a three-way catheter and establish continuous bladder irrigation. Keep the solution flowing at a rate sufficient to maintain patency and ensure that returns are clear. If a regular catheter is used, observe it closely. If drainage stops because of clots, irrigate the catheter as ordered, usually with 80 to 100 ml of normal saline solution, while maintaining sterile technique. Be sure to monitor intake and output closely.

Watch for septic shock, the most serious complication of prostatic surgery. Immediately report severe chills, sudden fever, tachycardia, hypotension, or other signs of shock. Start rapid infusion of I.V. antibiotics as ordered.

Watch for pulmonary embolism, heart failure, and acute renal failure. Monitor vital signs, central venous pressure, and arterial pressure.

Make the patient comfortable after an open procedure: Administer suppositories (except after perineal prostatectomy), and give analgesics to control incisional pain. Change dressings frequently.

Continue infusing I.V. fluids until the patient can drink enough on his own (2 to 3 qt [2 to 3 L]/day) to maintain adequate hydration.

Administer stool softeners and laxatives, as ordered, to prevent straining. Don’t check for fecal impaction because a rectal examination can cause bleeding.

Teaching about BPH

Teaching about BPH

After surgery, when the catheter has been removed, the patient may experience urinary frequency, dribbling and, occasionally, hematuria. Reassure the patient and family members that he’ll gradually regain urinary control.

Reinforce prescribed limits on activity. Warn the patient against lifting, performing strenuous exercises, and taking long car rides for at least 1 month after surgery because these activities increase bleeding tendency. Also caution him not to have sexual intercourse for at least several weeks after discharge.

Teach the patient to recognize the signs of urinary tract infection. Urge him to immediately report these signs to the physician because infection can worsen the inflammation and lead to further obstruction.

Instruct the patient to follow the prescribed oral antibiotic regimen, and tell him the indications for using gentle laxatives.

Urge the patient to seek medical care immediately if he can’t void at all, passes bloody urine, or develops a fever.

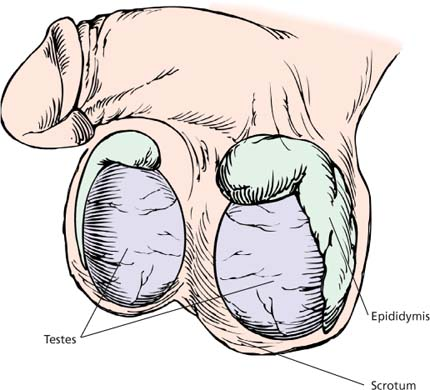

Epididymitis

Epididymitis, infection of the epididymis (the cordlike excretory duct of the testis), is one of the most common infections of the male reproductive tract. It usually affects adults and is rare before puberty.

Epididymitis usually results from pyogenic organisms, such as staphylococci, Escherichia coli, streptococci, chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Treponema pallidum. Infection usually results from established urinary tract infection and sexually transmitted disease (STD) or prostatitis extending to the epididymis through the lumen of the vas deferens. Rarely, epididymitis is secondary to a distant infection, such as pharyngitis or tuberculosis that spreads through the lymphatic system or, less commonly, the bloodstream.

Trauma may reactivate a dormant infection or initiate a new one. In addition, epididymitis is a complication of prostatectomy and may result from chemical irritation by extravasation of urine through the vas deferens.

Signs and symptoms

Unilateral, dull, aching pain radiating to the spermatic cord, lower abdomen, and flank

Extremely heavy feeling in the scrotum

Erythema

High fever

Malaise

Characteristic waddle in an attempt to protect the groin and scrotum while walking

Understanding orchitis

| Orchitis, an infection of the testes, is a serious complication of epididymitis. It also may result from mumps, which can lead to sterility, or less commonly, another systemic infection. | Signs and symptoms Typical effects of orchitis include unilateral or bilateral tenderness and redness, sudden onset of pain, and swelling of the scrotum and testes. Nausea and vomiting also occur. Sudden cessation of pain indicates testicular ischemia, which can cause permanent damage to one or both testes. Hydrocele also may be present. | Treatment Appropriate treatment consists of immediate antibiotic therapy or, in mumps orchitis, injection of 20 ml of lidocaine near the spermatic cord of the affected testis, which may relieve swelling and pain. Although corticosteroid use is experimental, such drugs may be used to treat nonspecific granulomatous orchitis. Severe orchitis may require surgery to incise and drain the hydrocele and to improve testicular circulation. Other treatments are similar to those for epididymitis. To prevent mumps orchitis, ensure that prepubertal males receive the mumps vaccine (or gamma globulin injection after contracting mumps). |

Treatment

Bed rest, scrotal elevation with towel rolls or adhesive strapping, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and analgesics (acute phase)

Ice bag applied to the groin area to reduce swelling and relieve pain (Heat is contraindicated because it may damage germinal cells, which are viable only at or below normal body temperature.)

Athletic supporter once pain and swelling subside to prevent pain

Corticosteroids to help counteract inflammation (use is controversial)

Epididymectomy under local anesthesia (if refractory to antibiotics)

Bilateral vasectomy in an older patient undergoing prostatectomy to prevent epididymitis as a postoperative complication (antibiotics alone may prevent it)

Nursing considerations

Watch closely for signs of abscess formation (a localized, hot, red, tender area) or extension of the infection into the testes. Closely monitor temperature, and ensure adequate fluid intake.

Because the patient is usually uncomfortable, administer analgesics as necessary. Allow him to rest in bed, legs slightly apart, with testes elevated on a towel roll. Suggest that he wear nonconstricting, lightweight clothing until the swelling subsides. Apply ice packs as needed for comfort.

Administer antibiotics and antipyretics as ordered. If epididymitis is secondary to an STD, treat the patient and his sexual partner(s) with appropriate antibiotics.

If the patient faces the possibility of sterility, suggest supportive counseling as necessary.

Teaching about epididymitis

Teaching about epididymitis

If the patient will take antibiotics after discharge, emphasize the importance of completing the prescribed regimen even after symptoms subside.

Suggest that the patient wear a scrotal support while sitting, standing, or walking.

If epididymitis is secondary to an STD, encourage the patient to use a condom during intercourse and to notify sex partners so that they can be adequately treated for infection.

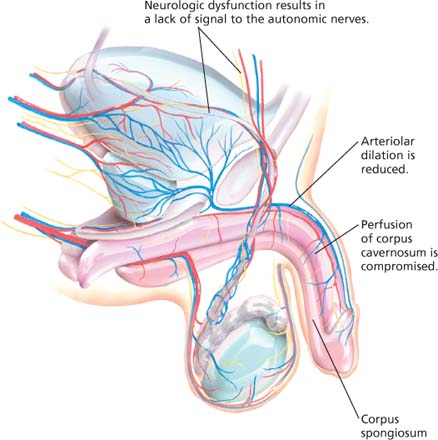

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) refers to the inability to attain or maintain penile erection long enough to complete intercourse. ED is characterized as primary or secondary. The patient with primary ED has never achieved sufficient erection. Secondary ED, which is more common and less serious than the primary form, implies that, despite the current inability, the patient has succeeded in completing intercourse in the past. Transient periods of ED aren’t considered dysfunctional and probably occur in 50% of males.

Three types of secondary ED occur:

Partial—The patient can’t achieve a full erection or keep his erection long enough to penetrate his partner.

Intermittent—The patient sometimes is potent with the same partner.

Selective—The patient is potent only with certain partners.

ED affects all age-groups but becomes more common with age. The prognosis depends on the severity and duration of ED and on the underlying cause.

Signs and symptoms

Long-standing inability to achieve erection

Sudden loss of erectile function

Gradual decline in function

History of medical disorders, drug therapy, or psychological trauma

Ability to achieve erection through masturbation but not with a partner (psychogenic rather than organic cause)

Depression (either a cause or a result of the impotence)

Treatment

Sex therapy that includes sensate focus therapy, improving verbal communication skills, eliminating stress, and reevaluating attitudes toward sex and sexual roles

Eliminating the cause (for organic impotence); psychological counseling to help the couple deal realistically with their situation and explore alternatives for sexual expression (if cause can’t be eliminated)

Surgically inserted inflatable or semirigid penile prosthesis (for organic impotence)

Sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), or tadalafil (Cialis) as an alternative to surgery

Nursing considerations

Help the patient feel comfortable about discussing his sexuality.

As needed, refer the patient to a physician, nurse, psychologist, social worker, or counselor trained in sex therapy.

Explore areas of stress with the patient. Help him develop relaxation techniques to reduce the stress.

If there are coexisting conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension, encourage the patient to comply with prescribed treatment.

After penile prosthesis surgery

Apply ice packs to the penis for 24 hours.

Empty the drainage device when it’s full.

If the patient has an inflatable prosthesis, instruct him to pull the scrotal pump downward to ensure proper alignment.

When ordered, have the patient practice inflating and deflating the device.

Teaching about erectile dysfunction

Teaching about erectile dysfunction

Provide instruction about the anatomy and physiology of the reproductive system and the human sexual response cycle as needed.

After penile implant surgery, instruct the patient to avoid intercourse until the incision heals,

usually in 6 weeks. Advise him to report signs of infection to the physician.

If the patient is using medication to treat ED, be sure to explain potential side effects or interactions with other medications the patient may be taking.

As a helpful guideline, inform the patient that the therapist’s certification by the American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors, and Therapists or by the American Society for Sex Therapy and Research usually ensures quality treatment. If the therapist isn’t certified by one of these organizations, advise the patient to ask about the therapist’s training in sex counseling and therapy.

Hydrocele

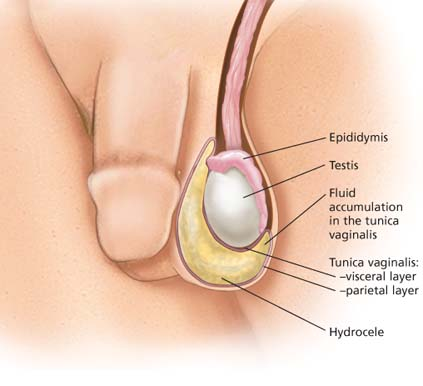

A hydrocele is a collection of fluid between the visceral and parietal layer of the tunica vaginalis of the testicle or along the spermatic cord. It’s the most common cause of scrotal swelling. It may be caused by an infection or trauma to the testes or epididymis or a testicular tumor.

Congenital hydrocele occurs when an opening between the scrotal sac and the peritoneal cavity allows peritoneal fluid to collect in the scrotum. The exact mechanism is unknown.

Signs and symptoms

Scrotal swelling and feeling of heaviness

Inguinal hernia (commonly accompanies congenital hydrocele)

Fluid collection, presenting as a flaccid or tense mass

Pain with acute epididymal infection or testicular torsion

Scrotal tenderness due to severe swelling

Treatment

Possibly no treatment, especially in newborns

Surgical herniography (for inguinal hernia with bowel in the sac)

Aspiration of fluid and injection of a sclerosing agent (for a tense hydrocele that impedes blood circulation)

Excision of the tunica vaginalis (for recurrent hydroceles)

Suprainguinal excision for a testicular tumor (detected by ultrasound)

Nursing considerations

Place a rolled towel between the patient’s legs and elevate the scrotum to help reduce swelling.

Apply heat or ice packs to the scrotum.

Monitor scrotal swelling.

Provide postoperative wound care, if appropriate.

Teaching about hydrocele

Teaching about hydrocele

Educate the patient about wearing a loose-fitting athletic supporter lined with soft cotton dressings.

Instruct the patient on how to take a sitz bath.

Advise the patient about the need to avoid tub baths (only using the sitz bath) postoperatively for 5 to 7 days.

Caution the patient that the hydrocele possibly may reaccumulate during the first month after surgery because of edema.

Prostate cancer

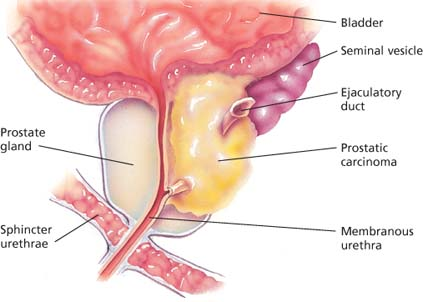

Prostate cancer is the most common neoplasm in males older than age 50; it’s a leading cause of male cancer death. Adenocarcinoma is the most common form; only seldom does prostate cancer occur as a sarcoma. Most prostate cancers originate in the posterior prostate gland, with the rest growing near the urethra. Malignant prostatic tumors seldom result from the benign hyperplastic enlargement that commonly develops around the prostatic urethra in older males.

Slow-growing prostate cancer seldom produces signs and symptoms until it’s well advanced. Typically, when primary prostatic lesions spread beyond the prostate gland, they invade the prostatic capsule and then spread along the ejaculatory ducts in the space between the seminal vesicles or perivesicular fascia. When prostate cancer is fatal, there is usually widespread bone metastasis.

Risk factors for prostate cancer include age (the cancer seldom develops in males younger than age 40), race (higher incidence in Blacks), and genetic factors. Men who have a first-degree relative with prostate cancer have twice the risk of developing it. Endocrine factors may also have a role, leading researchers to suspect that androgens speed tumor growth.

Signs and symptoms

Dysuria

Urinary frequency

Urine retention

Back or hip pain (signaling bone metastasis)

Hematuria (uncommon)

Edema of the scrotum (or leg in advanced disease)

Nonraised, firm, nodular mass with a sharp edge (in early disease) or a hard lump (in advanced disease)

Erectile dysfunction

Treatment

Radiation, prostatectomy, orchiectomy (removal of the testes) to reduce androgen production, and hormonal therapy with leuprolide (Lupron Depot) or goserelin (Zoladex)

Radical prostatectomy (for localized lesions without metastasis)

Suprapubic prostatectomy

Transurethral resection of the prostate to relieve an obstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Looking at prostatic enlargement in BPH

Looking at prostatic enlargement in BPH

Understanding epididymitis

Understanding epididymitis

Understanding erectile dysfunction

Understanding erectile dysfunction

Looking at a hydrocele

Looking at a hydrocele

Looking at prostate cancer

Looking at prostate cancer

Pathway for metastasis of prostate cancer

Pathway for metastasis of prostate cancer