M

MECHANICAL VENTILATION

A mechanical ventilator moves air in and out of a patient’s lungs. Although the equipment ventilates a patient, it doesn’t ensure adequate gas exchange. Mechanical ventilation may use either positive or negative pressure to ventilate a patient.

Positive-pressure ventilators exert a positive pressure on the airway, which causes inspiration while increasing tidal volume. The inspiratory cycles of these ventilators may vary in volume, pressure, or time. A high-frequency ventilator uses high respiratory rates and low tidal volume to maintain alveolar ventilation.

Negative-pressure ventilators create negative pressure, which pulls the thorax outward and allows air to flow into the lungs. Examples of such ventilators are the iron lung, the cuirass (chest shell), and the body wrap. Negative-pressure ventilators are used mainly to treat neuromuscular disorders, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis, and poliomyelitis.

Other indications for ventilator use include central nervous system disorders, such as cerebral hemorrhage and spinal cord transsection, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary edema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, flail chest, and acute hypoventilation.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

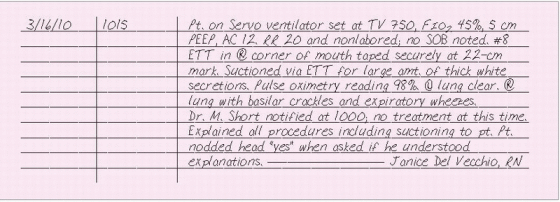

Document the date and time that mechanical ventilation began. Note the type of ventilator used as well as its settings, such as ventilatory mode,

tidal volume, rate, fraction of inspired oxygen, positive end-expiratory pressure, and peak inspiratory flow. Record the size of the endotracheal (ET) tube, centimeter mark of the ET tube, and cuff pressure or if the patient has a tracheostomy Describe the patient’s subjective and objective responses to mechanical ventilation, including vital signs pulse oximetry reading, ABG results, breath sounds, use of accessory muscles, comfort level, and physical appearance.

tidal volume, rate, fraction of inspired oxygen, positive end-expiratory pressure, and peak inspiratory flow. Record the size of the endotracheal (ET) tube, centimeter mark of the ET tube, and cuff pressure or if the patient has a tracheostomy Describe the patient’s subjective and objective responses to mechanical ventilation, including vital signs pulse oximetry reading, ABG results, breath sounds, use of accessory muscles, comfort level, and physical appearance.

Throughout mechanical ventilation, list any complications and subsequent interventions. Record pertinent laboratory data, including arterial blood gas (ABG) analyses and oxygen saturation findings. Also, record tracheal suctioning and the character of secretions.

If the patient is receiving pressure-support ventilation or is using a T-piece or tracheostomy collar, note the duration of spontaneous breathing and the patient’s ability to maintain the weaning schedule. If the patient is receiving intermittent mandatory ventilation, with or without pressure-support ventilation, record the control breath rate, time of each breath reduction, and rate of spontaneous respirations.

Record adjustments made in ventilator settings as a result of ABG levels, and document adjustments of ventilator components, such as changing, cleaning, or discarding the tubing. Also, record teaching efforts and emotional support given.

|

MEDICAL ADVICE, PATIENT OR FAMILY REOQUEST FOR

A patient or family member may seek your advice about a particular treatment the patient is receiving. You should be careful to provide objective information and not advice about the treatment. Giving medical

advice can be looked upon as providing medical treatment without a license and could subject you to legal concerns. Instead of offering advice, offer rationales for the treatment rather than recommending alternative treatment options or comparing one treatment to another.

advice can be looked upon as providing medical treatment without a license and could subject you to legal concerns. Instead of offering advice, offer rationales for the treatment rather than recommending alternative treatment options or comparing one treatment to another.

Evaluate what the patient knows and understands about his treatment and what he understands about what the doctor has told him about his treatment. Then, explain how the treatment works to alleviate or cure his condition. Suggest that he speak to his doctor again if he still doesn’t understand your explanation or if he still has questions or doubts. Inform the doctor of the patient’s or family member’s concerns, the information or teaching you’ve provided, and suggest that the doctor speak to the patient or family member.

If the patient or family member is asking your opinion about the abilities of a particular doctor, be careful what you say because you could be charged with defamation of character. Ask if a friend or family member has had previous experience with the doctor. If the patient or family member is questioning the care that the patient is receiving, you can suggest that he seek a second opinion. In fact, most doctors will suggest the patient ask for a second opinion before treatment is performed. If the patient or family member is asking about the skill of the doctor, ask why he asked the question.

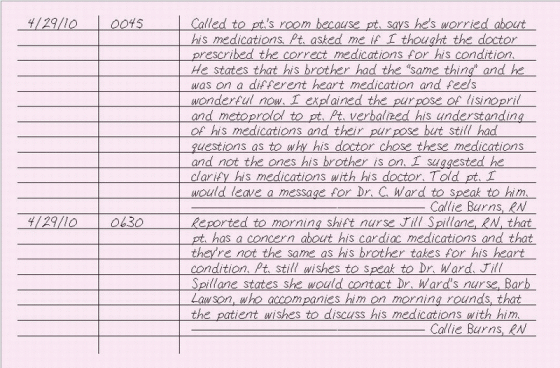

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

On your progress notes, document the patient’s or family member’s questions or concerns and how you responded. Also document any teaching that was provided and how well the information was understood. If you told the patient or family member that you would speak to his doctor, document when the doctor was called and to whom you spoke, such as the doctor, his receptionist, or the next shift nurse if the conversation with the patient or family member took place during a night shift, when it would be inappropriate to contact the doctor directly.

|

MEDICAL RECORDS, FAXING

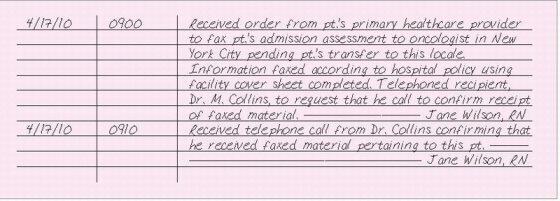

Faxing of medical records facilitates the exchange of information between healthcare providers; however, it’s essential that this practice doesn’t violate the confidentiality of the patient’s protected health information. The goal of the nurse responsible for faxing medical records should be to achieve a balance between protecting the patient’s health information in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and using technologies that facilitate the exchange of information. Faxing protected health information should be limited to circumstances in which the information is needed immediately and more secure transmission methods aren’t feasible. Protected health information sent by fax should be limited to the minimum necessary to accomplish the intended task. When such information is faxed, the sender must take safeguards to ensure only the intended recipient receives the information. When you’re faxing protected health information to an external fax number, verify receipt of the fax by either asking the recipient to fax back the cover sheet or calling the recipient to confirm that the fax was received. The confirmation sheet generated by the fax is insufficient as verification.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Include a cover sheet with all fax communication. The fax cover sheet should include the sender’s name; facility name; facility telephone and fax numbers; date and time of transmission; number of pages being faxed; recipient’s name, facility address, and telephone and fax numbers; summary of content being faxed (without including protected health information); and the name and number to call to verify receipt, report a transmittal problem or inform of a misdirected fax, and the instructions for handling a misdirected fax.

|

MEDICATION ERROR

Medication errors are the most common, and potentially the most dangerous, errors. Mistakes in dosage, patient identification, or drug selection by nurses have led to vision loss, brain damage, cardiac arrest, and death. (See Lawsuits and medication errors.)

A medication event report or incident report should be completed when a medication error is discovered. The nurse who discovers the medication error is responsible for completing the medication event report or incident report and for communicating the error to the patient’s doctor and the nursing supervisor.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

In your nurse’s note, describe the situation objectively and include the name of the doctor notified, the time of notification, and the doctor’s response. Avoid the use of such terms as “by mistake,” “somehow,” “unintentionally,” “miscalculated,” and “confusing,” which can be interpreted as admissions of wrongdoing.

LAWSUITS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

LAWSUITS AND MEDICATION ERRORSUnfortunately, lawsuits involving nurses’ drug errors are common.The court determines liability based on the standards of care required of nurses who administer drugs. In many instances, if the nurse had known more about the proper dosage, administration route, or procedure connected with a drug’s use, she might have avoided the mistake.

In Norton v.Argonaut Insurance Co. (1962), an infant died after a nurse administered injectable digoxin at a dosage level appropriate for elixir of Lanoxin, an oral drug.The nurse was unaware that digoxin was available in an oral form. The nurse questioned two doctors who weren’t treating the infant about the order but failed to mention to them that the order was written for elixir of Lanoxin. She also failed to clarify the order with the doctor who wrote it.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access