Long-Term Care

Susan J. Barnes

Kristen L. Mauk

INTRODUCTION

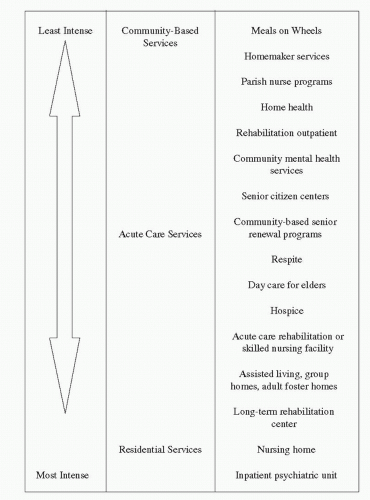

Long-term care (LTC) is an umbrella term that refers to a range of services that address the health, personal care, psycho-emotional, and social needs of persons with some degree of difficulty in caring for themselves. Although family members may assist those persons with age-related functional decline or those with disabilities, LTC is often needed as time progresses to bridge the gap in care. The ideal LTC services promote independence of the person for as long as possible and allow him or her to remain at home as appropriate. LTC may be required because of disability associated with birth defects, injury, or the aging process. The concept of LTC may best be visualized on a continuum. Between the two ends of the spectrum—inde pendence with minimal assistance at home versus skilled care in the nursing home—are many alternatives and options.

Care needs may be minimal or extensive (Figure 21-1). LTC services are offered in a variety of settings, as discussed in greater detail in this chapter. There is a growing trend in community-based services. Often, persons visualize a nursing home setting when they think of LTC, but this setting is used by only a small portion of the population at any given time.

Nurses are in an excellent position to design and implement innovative, cost-effective, and visionary care modalities to provide high-quality LTC services for patients while preserving their dignity and personhood. Because of the holistic perspective that nurses have of the patient, family, and community, they are in an excellent position to act as change agents in the process of healthcare reform.

In 2005, approximately 9 million people used LTC services in the United States (Chandra, Smith, & Paul, 2006), and 3.7 million Medicare enrollees used paid or unpaid personal caregivers in 1999 (most current data available; Administration on Aging, 2011). The cost of providing health care to persons older than age 65 is three to five times greater than for younger persons. The changing demographics of the baby boomer generation entering the older age group will have a significant impact on the whole of society (Lomastro, 2006). “One of the CDC’s [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] highest priorities as the nation’s health protection agency is to increase the number of older adults who live longer, high-quality, productive, and independent lives” (CDC & the Merck Foundation, 2007, p. i). In 2009, there were 39.6 million people over age 65 in America. By 2030, there will be approximately

72.1 million older adults, more than twice the number in 2000 (Administration on Aging, 2011).

72.1 million older adults, more than twice the number in 2000 (Administration on Aging, 2011).

For many persons, increased age is accompanied by one or more chronic illnesses. Reported health conditions among those in the Health and Retirement Study (National Institute on Aging, 2007) included (in order of frequency): arthritis, hypertension, heart conditions, diabetes, psychological/emotional problems, cancer, chronic lung disease, and stroke. These chronic conditions represent many of the frequent complaints of older adults as they experience the aging process. The National

Interview Health Survey (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007) found that nearly one third of adults older than 75 had fair or poor health. As the incidence of chronic disease grows, deficits in a person’s ability to perform self-care often follow, which can eventually lead to the need for LTC services. According to a document from the AARP (Houser, Fox-Grage, & Gibson, 2009), indicators of the need for LTC services include advanced age, living alone, poverty, less education, not owning a home, and not having a vehicle for transportation. The issue of LTC is sufficiently significant that the 2005 White House Conference on Aging focused on the “booming” dynamics of aging, tackling difficult issues relating to the baby boomer generation entering the older age group. The topics of the conference included promoting dignity, healthy independence, and financial security of older adults (Administration on Aging, 2008).

Interview Health Survey (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007) found that nearly one third of adults older than 75 had fair or poor health. As the incidence of chronic disease grows, deficits in a person’s ability to perform self-care often follow, which can eventually lead to the need for LTC services. According to a document from the AARP (Houser, Fox-Grage, & Gibson, 2009), indicators of the need for LTC services include advanced age, living alone, poverty, less education, not owning a home, and not having a vehicle for transportation. The issue of LTC is sufficiently significant that the 2005 White House Conference on Aging focused on the “booming” dynamics of aging, tackling difficult issues relating to the baby boomer generation entering the older age group. The topics of the conference included promoting dignity, healthy independence, and financial security of older adults (Administration on Aging, 2008).

Historical Perspectives

Caring for a client with complex health needs over a long period continues to be a challenge for the healthcare system. Throughout history, consideration given to the quality of care for older adults or other vulnerable populations is seen as a reflection of societal values (Koop & Schaeffer, 1976). In societies with more fluid resources, vulnerable populations such as the frail elderly or individuals with chronic illness are better cared for because of the availability of assistance with health care (Kalisch & Kalisch, 2004). History has demonstrated that in societies under the strain caused by famine, war, or social upheaval, the vulnerable may not be able to survive because of malnutrition, lack of health care, and the lack of ability of the family unit to provide support.

A review of LTC in the United States reveals several significant events that have led to our current system of providing care. Prior to the 20th century, older adults in the United States were usually cared for within extended family units (DeSpelder & Strickland, 2011). Those without family to care for them might have gone to a facility supported by a religious organization or by charitable citizens, such as a poorhouse or almshouse. Changes in medical care altered hospital stays and allowed LTC to evolve, with group rest homes and private charitable homes providing care for chronically ill, dependent persons. Because life expectancies continued to increase, the demand for LTC increased. Political response came in the form of the Social Security Act in 1932, which provided services for the elderly and chronically ill. In 1951, the first White House Conference on Aging was held. The first conference (now held every 10 years, with the next slated for 2015) focused on issues that affected the quality of life of the aged person.

Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, which was passed in 1965 and was a part of the Great Society of President Lyndon B. Johnson, provided medical insurance for the elderly (Medicare) and further involved the federal government in health care (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2011a). At the same time, in 1965, public policy was altered by the enactment of the Older Americans Act, which established aging networks throughout the states and funded community-based health services. Medicare opened the door for the government to dictate regulations and set the standard for care in formal caregiving settings. Evolution of the system included a restructuring of the Health Care Financing Authority into the CMS with the emphasis on improving the overall

process of coordinating care of complex illness in the context of managed care (Administration on Aging, 2008).

process of coordinating care of complex illness in the context of managed care (Administration on Aging, 2008).

Part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965 was Title XIX, Medicaid, to provide medical and health-related services for individuals and families with low incomes. Medicaid, a cooperative work between each state and the federal government, is the largest source of funds for services to the poor. Each state establishes its own eligibility standards, sets the rate of payment for services, and administers its own program (CMS, 2011a). Further changes in LTC were accomplished by Title XX of the Social Security Act Amendments, which made in-home services for medically indigent more widely available. In 1972 legislation was established that paid for intermediate care. The Omnibus Reconciliation Act, passed in 1987, included the Nursing Home Reform Act, which established high quality of care as a goal, along with the preservation of residents’ rights in LTC facilities. Among the changes included was the requirement that comprehensive assessments of all nursing home residents were to be done to determine the functional, cognitive, and affective levels of the residents and to be used in planning care. In addition, more specific requirements for nursing, medical, and psychosocial services were designed to attain and maintain the highest possible mental and physical functional statuses by focusing on patient outcomes (Harrington, Carrillo, Blank, & O’Brian, 2010). Resident rights were also clearly defined. Organizations such as the National Association for Home Care and Hospice and others (Kempthorne, 2004) have seen the need for continued work on health policy in this area and have made LTC a high priority on the legislative agenda.

The Affordable Health Care Act passed in 2010 promotes a major overhaul of the existing healthcare funding system aimed at providing care to all Americans. This act is likely to undergo major revision before being funded and taking effect, but it will serve as a catalyst for change. (Updates may be found at the White House website: http://www.whitehouse.gov/healthreform.)

As Western culture has evolved, the family structure has been modified by the increasing number of women who work outside the home and are unavailable to care for aging parents (Gaugler & Teaster, 2006; Wagner, 2006). Current cultural values have made it less common for extended families to live together. However, Latino and Asian cultures often include extended families, with several generations living in the same household or nearby, which makes it possible for family members to look after the interests of vulnerable elder members and limits the need for formal LTC services (Leininger, 2002). In many cultures, the concept of the “double caregiver” adds enormous stress to women who work and provide care for a family and ailing parents (Remennick, 2001). However, current U.S. values emphasize single-family dwellings, dual-income families, and transient lifestyles, which have led to families no longer residing in the same area, often geographically separated by great distance. This culturally driven environment has created a high demand for services from an already inefficient LTC care system.

The Continuum of Care

Community-Based Long-Term Care

The premise of community-based LTC is to provide seamless, comprehensive programs to facilitate aging in place (Willging, 2006). However, much work needs to be done to operationalize the seamless aspect of transitions. There is a variety of services available within

the LTC continuum. Current trends advocate using a case management approach to coordinate services and to ensure that individuals receive services in an efficient, timely fashion. Case management promotes aging in place with chronic illness, trying to keep a person in the home setting for a long as possible. The LTC system may be confusing to clients and families, but case managers can help to arrange and coordinate services such as Meals on Wheels, medical care, home health aides, and companion services. For older adults, the role of the geriatric care manager is an emerging one. Professional geriatric care managers (PGCMs) help families care for their older relatives while promoting independence. The National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers (2011) lists services that families might expect with a PGCM as follows:

the LTC continuum. Current trends advocate using a case management approach to coordinate services and to ensure that individuals receive services in an efficient, timely fashion. Case management promotes aging in place with chronic illness, trying to keep a person in the home setting for a long as possible. The LTC system may be confusing to clients and families, but case managers can help to arrange and coordinate services such as Meals on Wheels, medical care, home health aides, and companion services. For older adults, the role of the geriatric care manager is an emerging one. Professional geriatric care managers (PGCMs) help families care for their older relatives while promoting independence. The National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers (2011) lists services that families might expect with a PGCM as follows:

Conduct care-planning assessments to identify problems and to provide solutions.

Screen, arrange, and monitor in-home help or other services, including assistance in hiring a qualified caregiver for home care.

Provide short- or long-term assistance for caregivers living near or far away.

Review financial, legal, or medical issues and offer referrals to geriatric specialists.

Provide crisis intervention.

Act as a liaison to families at a distance, overseeing care, and quickly alerting families to problems.

Assist with moving an older person to or from a retirement complex, assisted care home, or nursing home.

Provide consumer education and advocacy.

Offer eldercare counseling and support.

Related services for the frail elder or individual with chronic illness could also include legal services, adult protective services, area councils on aging, ombudsman programs, senior centers, and elder-advocacy groups. Older adults with chronic illnesses that are rehabilitative may receive assistance with recovery through Medicare, which pays for inpatient and limited outpatient therapies ordered by a physician. Respite care for family members who care for loved ones with chronic illness and disability is also a community-based service.

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is another community-based alternative that promotes aging in place (Boult & Wieland, 2010). This program is an evidence-based model of care whose services are often covered by Medicare and Medicaid. The National PACE Association (2011) states that the average user is 80 years old, and preliminary studies suggest that involvement in a PACE program may slow functional decline for older adults. The PACE model combines dollars from different funding streams to deliver a comprehensive set of services focused on the health and well-being of the individual (National PACE Association, 2011). The number of states with participating organizations has increased to 30 in the last few years (the list of states with programs is found on the PACE website at: http://www.npaonline.org). Continuing evaluation of this program in terms of cost benefit to the funding agencies may make it available on a wider scale.

Residential Long-Term Care Settings

Residential LTC facilities are formal, organized agencies that provide care for persons unable to live alone because of physical or other problems, but who do not require hospitalization. Persons living in residential care are not called patients, but residents, because the LTC setting is their home. The three most common types of residential LTC facilities are group homes,

assisted-living centers, and nursing homes. Many retirement communities combine independent living facilities and assisted living facilities, although these represent two different levels of care. Those living independently in a retirement community may do so because of declining health caused by chronic illness, safety factors, frailty, and the need for socialization. The decision to move from one’s own home to a community living situation is difficult and often involves the advice of family members who are concerned about the older adult’s ability to live alone safely. LTC residents are a vulnerable population who tend to have more chronic illnesses and may require advocacy from health or social professionals.

assisted-living centers, and nursing homes. Many retirement communities combine independent living facilities and assisted living facilities, although these represent two different levels of care. Those living independently in a retirement community may do so because of declining health caused by chronic illness, safety factors, frailty, and the need for socialization. The decision to move from one’s own home to a community living situation is difficult and often involves the advice of family members who are concerned about the older adult’s ability to live alone safely. LTC residents are a vulnerable population who tend to have more chronic illnesses and may require advocacy from health or social professionals.

Group homes. Group homes are also referred to as personal care homes, foster homes, domiciliary care homes, board and care homes, and congregate care homes. The philosophy embraces a home environment with a limited number of residents who share common characteristics in needing assistance with such things as activities of daily living, shopping, cleaning, and medication management. Much like a boarding house, the owner of the home provides services such as meals, laundry and cleaning, medication management, and a safe environment. These homes are licensed by the state. This type of care is most appropriate for those with uncomplicated medical problems. Payment for group homes can be private, although in some states, it may be covered by Welfare. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has sponsored research in creating innovative and livable homes under the Green House Project (more information may be found in the research literature and at: www.thegreenhouseproject.org).

Assisted-living centers. Persons in assisted living are those who require some type of help with activities of daily living. According to the National Center for Assisted Living (2011), there are more than 900,000 individuals living in assisted living, and of those 64% require help with bathing, 39% need help with dressing, 26% need help with toileting, 19% need help with transferring, and 12% need help with eating. Of these residents, 81% need help with medication. Assisted living has taken over approximately 15% of what was previously the nursing home population (Kinosian, Stallard, & Wieland, 2007).

Because Medicare, Medicaid, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) do not pay for assisted living, the cost for this living arrangement and services are paid for out of pocket. Assisted living centers may be found as free-standing facilities, as part of retirement communities, or attached to nursing homes to allow for smoother transition of care for those expected to need skilled nursing in the future.

The National Center for Assisted Living (2011) has summarized the characteristics of the 36,000 assisted living centers in the United States. The typical profile of a resident in assisted living is an 86-year-old woman who is ambulatory but needs help with at least two activities of daily living. Residents’ average age in 2006 was 85 years, and the average length of stay was 28.3 months. One third of these residents will die, 59% will move into another nursing facility, and the remainder will return home or to other living situations. From these statistics, it is evident that although today’s older adults value their independence, the frailties that accompany old age make it necessary for more than 900,000 people in the United States to have some assistance with everyday activities.

Although assisted living facilities are accountable to a board of directors and may employ a registered nurse (RN) consultant, the care is generally provided by aides, with licensed practical nurses (LPNs) used regularly to supervise daily services. Assisted living facilities provide autonomy for older adults, allowing them

to live in a safe, home-like environment adapted for those with physical challenges. Assisted living provides personal space in the form of apartments or suites and also provides meals through community dining as well as transportation and social activities.

to live in a safe, home-like environment adapted for those with physical challenges. Assisted living provides personal space in the form of apartments or suites and also provides meals through community dining as well as transportation and social activities.

CASE STUDY

Mrs. Saltano is an 89-year-old widow who lived alone for 2 years after her husband of 51 years died of colorectal cancer. For most of their lives, Mr. and Mrs. Saltano lived in the same neigh-borhood and in the same house where they raised their five children. Mrs. Saltano planned to stay in the family home after her husband’s death, but she experienced bouts of loneliness and social isolation, despite being an active member of her local church before and after his death. She began to experience the effects of chronic illnesses, including having a bilateral knee replacement because of pain and decreased mobility from arthritis, and taking more medications to control her high blood pressure and lower her cholesterol. With advancing age, Mrs. Saltano also developed diabetes and some mild memory loss that her children found concerning. After one visit with the family at Christmas, Mrs. Saltano’s eldest daughter suggested that her mother explore the possibility of going to a retirement community designed for older adults.

Mrs. Saltano was absolutely opposed to leaving the home she had shared with her husband and where they had raised their family. She did not want to be in an “institution,” as she called it, but she admitted to having begun to have difficulty driving as a result of failing vision, and said she did not feel safe living alone. Mrs. Saltano did consent to visit a nearby retirement community with two of her adult children and found that some old friends of hers who were also widowed were living there. Her friends seemed happy and active. The apartment she would have gave her privacy (and had its own kitchenette, refrigerator, and large bathroom) but also allowed the staff to check on her. Meals were served in a nice dining room with linen tablecloths and a formal menu, and a library, big screen TV, pool table, and exercise room were available. A beauty shop was on the premises, and transportation to doctors’ offices and shopping was available for a nominal charge. Mrs. Saltano slowly warmed to the idea of moving to the continuous care retirement community, and so the arrangements were made. The quality of Mrs. Saltano’s life improved significantly through socialization and activities in this new environment. Her adjustment to a change in living situation was facilitated by the attitudes of her children, the staff, and other residents.

Discussion Questions

What factors prompted Mrs. Saltano’s children to encourage her to consider another living arrangement?

From the information in this chapter, was moving to a continuous care retirement community a prudent choice for Mrs. Saltano? Why or why not?

What problems and issues with adaptation to her new home is Mrs. Saltano likely to face?

What interventions might be helpful to assist with her adjustment?

Skilled nursing facilities or nursing homes. Nursing home is a term used to refer to a facility that has either skilled nursing services and/or intermediate care. Nursing homes are LTC facilities for individuals with chronic illness, who are medically frail, or who are disabled. The level of care may be described as residential, long-term, non-emergent, or custodial care. A number of facilities may include an intermediate care or rehabilitation unit for individuals who need assistance in re-establishing self-care abilities.

The majority of such agencies are “for profit.” Exceptions are agencies generally associated with churches or other nonprofit organizations such as the VA. The Veterans Health Admini-stration (VHA) predicted that the number of veterans older than age 85 will double in the next decade and that the VHA-enrolled veterans in this oldest old age group will increase sevenfold, resulting in a 22-25% increase in both nursing home and community-based services. The VHA currently uses 90% of its LTC resources on nursing home care. For veterans, age and marital status were found to be significant predictors of the use of LTC services (Kinosian et al., 2007).

Agencies that receive income from the CMS are required to meet minimum state and federal standards. Standards address items such as: nutritional and fluid intake; provision of social interaction and activities; and support services such as physical therapy, rehabilitation therapy, housekeeping, and laundry services. There is a continued concern by those employed in LTC settings that facility structure and staffing are often based on minimal standards that contain costs instead of considering first what is desirable or needed for the client. However, as the baby boomer generation ages, it is expected that its interest in this issue will influence the creation of higher standards, and quality of care may improve in LTC facilities.

Approximately 5% of the elderly population reside in nursing homes in the United States, and 28% pay for their own care. Care in nursing homes may be funded by the individual (self-pay), insurance, Medicare (with limits), or Medicaid. To be eligible for Medicaid payment for residential care, the client must have limited assets with which to pay for the services required. Often an LTC resident will enter a nursing home, paying for services until his or her estate is spent down, and then Medicaid pays for care until the client’s death (AARP, 2010).

Much of the care provided in the traditional nursing home setting is considered custodial care. Rehabilitative services are provided for those who have the capacity to regain function. Because the institutionalized individual may require a great deal of help with the physical aspects of care, such as bathing, dressing, eating, and space maintenance, the cognitive needs (emotional, psychological, and spiritual) may be considered less important. Activity programs are sometimes geared only toward one segment of the facility population. Care in LTC settings should include not only appropriate physical care, but also appropriate social and cognitive stimulation.

Long-Term Care Recipients—A Vulnerable Population

Vulnerable individuals are those who are at increased risk for loss of autonomy, loss of self-will, injustice, loss of privacy, and increased risk for abuse. A vulnerable adult is defined as an individual who is either being mistreated or is in danger of mistreatment and who because of age

and/or disability is unable to protect him/herself (Teaster, 2002). A vulnerable individual can be described as one who has been judged by someone to be a nonperson. Examples of vulnerable persons in LTC may include those with physical or mental or emotional problems, the elderly, those with dementia, and those who have been in prison. In a culture that values youth, energy, strength, and the ability to work, many devalue elders or those with chronic illness. Laws and practices differ between states in the areas of abuse, neglect, and protective services. Ultimately, it is the care providers and administrators in LTC who are responsible for maintaining an environment that supports the unique personhood of the client and protects the vulnerable.

and/or disability is unable to protect him/herself (Teaster, 2002). A vulnerable individual can be described as one who has been judged by someone to be a nonperson. Examples of vulnerable persons in LTC may include those with physical or mental or emotional problems, the elderly, those with dementia, and those who have been in prison. In a culture that values youth, energy, strength, and the ability to work, many devalue elders or those with chronic illness. Laws and practices differ between states in the areas of abuse, neglect, and protective services. Ultimately, it is the care providers and administrators in LTC who are responsible for maintaining an environment that supports the unique personhood of the client and protects the vulnerable.

Many individuals requiring LTC have already lost some autonomy and self-will because of illnesses that affect the individual’s ability to make decisions or carry out intentional behavior. Vulnerability is of special concern in these individuals. Decisions must be made for them regarding many aspects of life, such as eating, bathing, medication administration, socialization, and exercising religious practices. Some persons may benefit from the services of a guardian, discussed later in this chapter.

Abuse in the home or in a residential facility is an extreme threat to the autonomy of the client. If the nurse providing care is the first to observe signs and symptoms of mistreatment, reporting these observations to Adult Protective Services (APS) (or other public agency, as designated in the particular state) is required by law. In the home, the home healthcare nurse may be in a position to discover abuse and act as the primary advocate to prevent further abuse. The nurse may work with various agencies to ensure that appropriate intervention is made. Because elder mistreatment is often subtle, the nurse must be persistent in reporting signs until action is taken. If abuse or neglect of the community-based client is profound, a move to residential care may be indicated.

PROBLEMS AND ISSUES IN LONG-TERM CARE

There are a number of issues in LTC, ranging from overall system breakdown to individual treatment issues for clients in the system. The issues mentioned in this chapter are not an exhaustive list but can be considered an introduction to current problems.

Provision of Care

Along the continuum of LTC, problems in the provision of care include organization of services and access to care, gaps in public policy, funding, staffing, and standards of care. Specific issues vary within individual states or communities. It is imperative that the professional nurse involved in LTC is cognizant of the local and state issues that affect delivery and quality of LTC services. Being a political activist in order to further the issues of the recipients of LTC is also important.

Organization of Services

It was not surprising that the second most important resolution that came from the White House Conference on Aging in 2005 was the need for a more comprehensive and well-coordinated LTC strategy (Lomastro, 2006). In community-based LTC, the array of services in a given community may not be organized according to any hierarchy. Each specialized service, such as home care, elder daycare, hospice, or nutrition

programs, was most likely begun in response to a specific need or business opportunity in the community. It is often necessary for a program of LTC to be pieced together from a number of different organizations to meet one client’s needs. This is especially true for communitydwelling residents.

programs, was most likely begun in response to a specific need or business opportunity in the community. It is often necessary for a program of LTC to be pieced together from a number of different organizations to meet one client’s needs. This is especially true for communitydwelling residents.

Partial help with this problem comes from the United Way, a nonprofit service-based agency. The United Way publishes a resource book in larger cities that describes community programs and services. (This publication can be obtained by calling the local United Way office or obtaining the list online at http://www.unitedway.org.) This resource book assists clients, family, and care providers in identifying appropriate services, phone numbers, and eligibility requirements. Many times, individuals with chronic illness and their families are not aware that when they are involved with one system (such as a nursing home), they have access to other services (such as hospice). Individuals with chronic illnesses often view access to the LTC system as complicated and overwhelming. Those with chronic illnesses and their families may have a limited amount of energy to invest in problem solving and identifying the best options. Often, access to the LTC system is controlled by gatekeepers who have minimal training and experience with complex medical conditions. Rules may be seen as arbitrary, and appear to exclude the very individuals intended to benefit from programs.

With the utilization of more case management for individuals with chronic illness, whether through the local or federal VA, state health and human services divisions, or private companies, some progress is being made in assisting community-dwelling individuals to more effectively access LTC services. However, for most clients and families, access to the LTC system remains confusing and complex.

Gaps in Public Policy

In the United States, the primary responsibility for paying for LTC services is with the individuals who need those services. Medicare pays for limited skilled nursing care, up to 100 days, associated with an acute illness requiring at least 3 days of hospitalization (Houser et al., 2009; Medpac, 2010). Partially because of the funding sources and partially because of the method of development of services, there are gaps that exist in LTC services. Much policy work needs to be done related to transitions that individuals experience moving from one type of service to another because no overall umbrella of comprehensive care exists. The current healthcare reform effort is at least partially aimed at making transitions more seamless. Pharmaceutical costs, extended home health care, and rehabilitative services are problematic for many in LTC. For those unable to self-pay, some go without services or medications.

Funding

Gaps in service and public policy are both related to funding issues. In 2009, $144 billion was paid by state and federal agencies to free-standing nursing home facilities (Harrington et al., 2010). Medicaid alone spent $94.5 billion on LTC services in 2005 (Houser et al., 2009). As previously mentioned, a significant number of residents in nursing homes and other residential care facilities pay privately for their care until their estate is spent down, at which time state and federal funding may take over (Houser et al., 2009). Many persons may be eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. Although these

persons do not generally report difficulty obtaining medical care, 58% of those who need LTC report their needs as being unmet. This problem has led to additional consequences such as falls (Komisar, Feder, & Kasper, 2005). Private insurance and nonprofit organizations also provide services for those in need of LTC. However, beyond the nursing home setting, piecing together a comprehensive LTC program for a frail elder with comorbidities who wishes to remain in the community is challenging. Certification for eligibility for certain benefits, such as extended home care, is strict and for a limited amount of time only.

persons do not generally report difficulty obtaining medical care, 58% of those who need LTC report their needs as being unmet. This problem has led to additional consequences such as falls (Komisar, Feder, & Kasper, 2005). Private insurance and nonprofit organizations also provide services for those in need of LTC. However, beyond the nursing home setting, piecing together a comprehensive LTC program for a frail elder with comorbidities who wishes to remain in the community is challenging. Certification for eligibility for certain benefits, such as extended home care, is strict and for a limited amount of time only.

Resources, whether private or public, are limited. Community-dwelling elders may be eligible for Medicare to pay for certain services, such as home health care, but only as long as some rehabilitation progress can be documented. Once progress stops, and the condition is considered chronic, the individual may have to pay privately for rehabilitative and home services. For individuals who have lived through the Great Depression, World War II, and other historical events that have required genuine frugality, spending nearly $100 to pay for less than an hour of a home visit from an agency RN is not a viable option. Many older adults from working class backgrounds do without needed care rather than pay privately. One study found that the greater the use of paid home care in a state, the less likely persons were to report unmet need (Komisar et al., 2005). This suggests that state policies can make a difference in the health care of their citizens.

It is important to consider the entitlement to care that older adults and those with chronic illness possess because of Social Security programs. These programs were designed to provide some comfort and security to the older individual. One view is that society has an obligation to provide for those in need, particularly the elderly, because of the labor and service that they have provided (Tobin & Salisbury, 1999). Another view is that society is obligated to provide care for frail and chronically ill elders because of the sanctity of all human life, and not simply because of work undertaken during the adult life. Philosophical origins play an important part not only in the establishment and continuation of programs, but also in setting standards for ongoing programs.

Alternative financing for LTC needs to be explored. Although both PACE (mentioned previously in this chapter) and social managed care plans offer alternatives to nursing homes and promote aging in place, it is evident that their scope and availability are significantly limited. In Arkansas, research revealed a need to expand health services because of unmet needs, suggesting policy recommendations to improve access to community-based care (Stewart, Felix, Dockter, Perry, & Morgan, 2006). In addition, a few strategies to fund LTC costs have arisen from the financial sector: reverse mortgages and life settlement. Both concepts focus on helping individuals liquidate assets (for example, a home or life insurance policy) to provide cash to privately pay to enter or remain in a facility (Feaster, 2006). It is only since 2000 that using one’s life insurance as a financial tool to obtain relatively quick cash has been considered. However, individuals considering this option should consult with a financial adviser.

Staffing

Healthcare agencies that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding are licensed by each state or are accredited by a recognized accrediting agency. Each agency must meet requirements in

staffing. Two main issues in staffing are the training of the staff member and the staff-to-client ratio (Harrington et al., 2010).

staffing. Two main issues in staffing are the training of the staff member and the staff-to-client ratio (Harrington et al., 2010).

Standards for required staff training are often minimal. For example, medication aides working in an assisted-living center may be required to attend a 6-week training course, yet the medication regimens for the assisted-living center clientele may be extremely complex. For proper medication management, much more time is required to educate a person on the pharmacologic effects of medications, side effects, and complications. Although assisted-living centers are required to have an RN available, that one RN may act as a consultant for multiple centers under the same ownership umbrella. The actual individual who “supervises” the medication aides may be an LPN who works a 40-hour week.

Qualifications for the director or administrator of an assisted-living center are minimal and may be as little as possessing a GED and attending an industry-sponsored seminar lasting 2 weeks or less. The majority of staff working in such facilities may be minimally trained personnel, and client safety is a legitimate concern.

Staffing challenges in providing home health care are also significant. State requirements vary for home health aides, but no training program is more than 8-12 weeks in length. Often, aides are trained and then expected to work independently, with little supervision.

Staffing in nursing homes is a continuing issue. There is conclusive evidence that a positive relationship exists between nursing staffing and quality of nursing home care. Fewer RN and nursing assistant hours are associated with quality-of-care deficiencies (Arling, Kane, Mueller, Bershadsky, & Degenholtz, 2007; Harrington, Zimmerman, Karon, Robinson, & Beutel, 2000). The turnover rate for nursing assistants can be as high as 40-100% in some facilities. High turnover rates have been associated with poor quality care (Castle, Engberg, & Men, 2007). Recruitment and retention of qualified nursing assistants is an ongoing problem. Creating an environment that promotes teamwork, addresses care-related stressors, promotes positive communication, reduces paper-work inefficiencies and staffing shortages, and has high organizational morale has been shown to increase job satisfaction and commitment to the organization, but there are many other factors to consider in the complex process of staff turnover in these settings (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2011; Arling et al., 2007; Cherry, Ashcraft, & Owen, 2007; Donoghue & Castle, 2006; Sikorska-Simmons, 2006). The decreasing level of RN staffing is also of growing concern, and yet reimbursements and prospective payments have been reduced in some cases, making it impossible to increase the number of RNs in residential facilities.

To complicate this situation, there is a projected shortage of healthcare professionals. Half of the RN workforce is at least 45 years old. It is estimated that by 2025 there will be a shortage of at least 260,000 RNs because of a number of significant factors, including the population growth, retirement of nurses in the current workforce, and the lack of faculty to educate willing students in nursing programs (Harrington, 2008).

Standards

Residential and community-based LTC facilities that accept government payments are regulated by federal and state mandates. Agencies and institutions involved in providing LTC that receive outside funding are required to meet

certain standards and undergo regular inspection (Harrington et al., 2010).

certain standards and undergo regular inspection (Harrington et al., 2010).

Requirements change frequently. Part of the responsibility of both the facility administrator and the director of nursing in any LTC facility is to be aware of and implement changes that are made necessary as a result of changes in state and federal requirements. In home health agencies, the number and type of visits that can be reimbursed by insurance or Medicare are limited. If evidence in regard to why the visits were made and what health-related goal was achieved is unclear, the payer may bill the agency back for those services, which can be financially devastating to an organization.

Nursing homes undergo an initial survey to become certified and then undergo inspection no less than every 15 months with an average of every 12 months (Harrington et al., 2010). State surveyors evaluate both process and outcomes of nursing home care in several areas. Tags are assigned depending on the severity of the violation. If deficiencies are found, follow-up surveys may be conducted. If care is so poor that residents are deemed to be in danger, facilities can be fined large amounts of money, be prohibited from admitting any residents, and even be closed for severe violations. Agencies must demonstrate that the staff meet educational requirements, that residents are receiving adequate care, and that documentation is appropriate. Requirements vary for various types of agencies and are complicated. Most states post the results of surveys on a public website, where family members can access information and compare facilities when making decisions about placing loved ones into LTC. Current national survey results are available through the CMS website (http://www.cms.gov).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access