Integumentary care

Diseases

Acne vulgaris

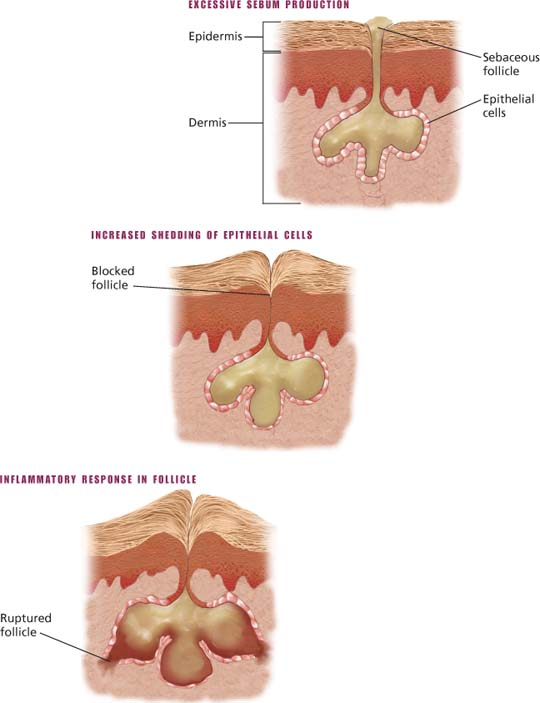

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the skin glands and hair follicles that appears as comedones, pustules, nodules, and nodular lesions. This disorder, which tends to run in families, affects nearly 85% of adolescents with a westernized lifestyle, although lesions can appear as early as age 8. Acne affects boys more commonly and more severely; however, it typically occurs in girls at an earlier age and tends to affect them for a longer time, sometimes into adulthood. With treatment, the prognosis is good.

Signs and symptoms

Pain and tenderness around the area of the infected follicle

Acne lesions, most commonly on the face, neck, shoulders, chest, and upper back

Area around the infected follicle that appears red and swollen

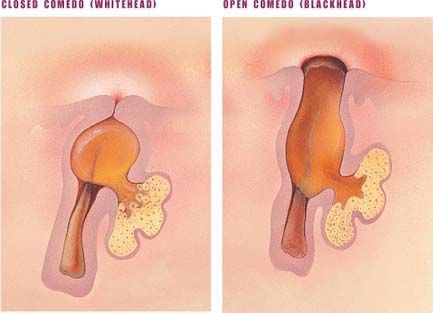

Acne plug that may appear as a closed comedo, or whitehead (if it doesn’t protrude from the follicle and is covered by the epidermis), or as an open comedo, or blackhead (if it protrudes and isn’t covered by the epidermis)

Inflammation and characteristic acne pustules, papules or, in severe forms, acne cysts or abscesses

Visible scars

Treatment

Benzoyl peroxide (powerful antibacterial)

Clindamycin (Cleocin), erythromycin (Akne-mycin), or antibacterial agents alone or in combination with tretinoin (retinoic acid [Retin-A] or topical vitamin A)

Tetracycline to decrease bacterial growth

Oral isotretinoin (Amnesteem)

Birth control pills (such as Ortho-TriCyclen) or spironolactone to produce antiandrogenic effects (in females)

Intralesional corticosteroid injections

Exposure to ultraviolet light (but never when a photosensitizing agent, such as isotretinoin, is being used)

Cryotherapy

Acne surgery

Nursing considerations

Assist the patient in identifying and eliminating predisposing factors.

Encourage good personal hygiene and the use of oil-free skin care products. Discourage picking, scratching, or squeezing the lesions to eliminate secondary bacterial infections and scarring.

Monitor liver function studies and serum triglyceride levels when isotretinoin is used.

Be alert for possible complications associated with using systemic antibiotics (such as tetracycline), including sensitivity reactions, GI disturbances, and liver dysfunction.

Remember that tetracycline is contraindicated during pregnancy because it discolors the fetus’s unerupted teeth.

Be alert for possible adverse reactions associated with using isotretinoin, including possible skin irritation, dry skin and mucous membranes, and elevated triglyceride levels.

Encourage the patient with acne to verbalize his feelings, including embarrassment, fear of rejection by others, and disturbed body image. Note the importance of body image in growth and development. Encourage him to develop interests that support a positive self-image and deemphasize appearance.

Teaching about acne

Teaching about acne

Explain the causes of acne to the patient and his family. Encourage the patient to seek medical treatment if extensive acne develops.

Make sure the patient and his family understand that the prescribed treatment will improve acne more than will a strict diet or excessive scrubbing with soap and water. Advise using sunscreen whenever outdoors to prevent aggravating the skin.

Instruct the patient receiving tretinoin to apply it at least 30 minutes after washing his face and at least 1 hour before bedtime. Warn against using it around the eyes or lips. Explain that after treatments, the skin should look pink and dry and that some amount of peeling is normal in the morning when tretinoin has been applied at night. Tell the patient that if the skin appears irritated, the preparation may have to be weakened or applied less often. Advise the patient to avoid exposure to sunlight while wearing the solution or to use a sunscreen.

If the prescribed regimen includes tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide, advise the patient to avoid skin irritation by using one preparation in the morning and the other at night. Also advise the patient that acne typically flares up during the early course of treatment, probably because early, developing lesions are uncovered.

Instruct the patient taking tetracycline to do so on an empty stomach. Advise him not to take tetracycline with antacids or milk because it interacts with their metallic ions and is then poorly absorbed. Explain that some studies suggest that a diet high in cow’s milk and carbohydrates is associated with increased occurrence and severity.

Tell the patient taking isotretinoin to avoid vitamin A supplements, which can worsen adverse effects. Warn the patient against giving blood during treatment with this drug and to avoid alcohol ingestion. Also, teach how to deal with the dry skin and mucous membranes that usually result during treatment. Instruct the female patient about the severe risk of teratogenicity. Encourage the patient to schedule and follow up with the necessary laboratory studies.

Teach the patient and his family techniques to maintain a well-balanced diet, get adequate rest, and manage stress.

Inform the patient that acne takes a long time—in some cases, years—to clear. Encourage continued local skin care even after acne clears.

Basal cell carcinoma

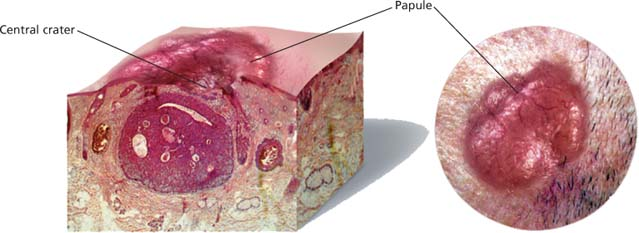

Basal cell carcinoma, also known as basal cell epithelioma, is a slow-growing, destructive skin tumor that usually occurs in people older than age 40. Forty to fifty percent of Americans age 65 or older will have either basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma at least once during their lifetime. It’s most prevalent in blond, fair-skinned males, and it’s the most common malignant tumor that affects whites. The two major types of basal cell carcinoma are noduloulcerative and superficial.

Prolonged sun exposure is the most common cause of basal cell carcinoma. Indeed, 90% of tumors occur on sun-exposed areas of the body. Arsenic ingestion, radiation exposure (including tanning beds), burns, immunosuppression and, rarely, vaccinations are other possible causes.

Although the pathogenesis is uncertain, some experts hypothesize that basal cell carcinoma develops when undifferentiated basal cells become carcinomatous instead of differentiating into sweat glands, sebum, and hair.

Signs and symptoms

Lesions that appear as small, smooth, pinkish, and translucent papules (early-stage noduloulcerative), particularly on the forehead, eyelid margins, and nasolabial folds

Telangiectatic vessels crossing the surface

Lesions that may be pigmented

As lesions enlarge, centers that become depressed and borders that become firm and elevated (rodent ulcers)

Multiple oval or irregularly shaped, lightly pigmented plaques that may have sharply defined, slightly elevated, threadlike borders (superficial basal cell carcinomas)

Inspection of the head and neck may show waxy, sclerotic, yellow to white plaques without distinct borders. These plaques may resemble small patches of scleroderma and may suggest sclerosing basal cell carcinomas (morphea-like carcinomas).

Treatment

Curettage and electrodesiccation for small lesions

Topical fluorouracil for superficial lesions; produces marked local irritation or inflammation in the involved tissue but no systemic effects

Microscopically controlled surgical excision to remove recurrent lesions until a tumor-free plane is achieved; possible skin grafting after removal of large lesions

Irradiation, if the tumor location requires it and for elderly or debilitated patients who might not tolerate surgery

Chemosurgery for persistent or recurrent lesions; consists of periodic applications of a fixative paste (such as zinc chloride) and subsequent removal of fixed pathologic tissue until the tumor is eradicated

Cryotherapy, using liquid nitrogen, to freeze and, ultimately, kill cells

Nursing considerations

Listen to the patient’s fears and concerns. Offer reassurance, when appropriate. Remain with the patient during periods of severe stress and anxiety. Provide positive reinforcement for the patient’s efforts to adapt.

Arrange for the patient to interact with others who have a similar problem.

Assess the patient’s readiness for decision making; then involve him and family members in decisions related to his care whenever possible.

Watch for complications of treatment, including local skin irritation from topically applied chemotherapeutic agents and infection.

Watch for radiation’s adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, hair loss, malaise, and diarrhea. Provide reassurance and comfort measures, when appropriate.

Teaching about basal cell carcinoma

Teaching about basal cell carcinoma

To prevent disease recurrence, tell the patient to avoid excessive sun exposure and to use a strong sunscreen to protect his skin from damage by ultraviolet rays. If he must be out in the sun, tell him to avoid the hours of strongest sunlight and to cover up with protective clothing.

Advise the patient to relieve local inflammation from topical fluorouracil with cool compresses or with corticosteroid ointment.

Instruct the patient with noduloulcerative basal cell carcinoma to wash his face gently when ulcerations and crusting occur; scrubbing too vigorously may cause bleeding.

As appropriate, direct the patient and his family to facility and community support services, such as social workers, psychologists, and cancer support groups.

Burns

A major burn is a devastating injury, requiring painful treatment and a long period of rehabilitation. Burns can be fatal, permanently disfiguring, and incapacitating, both emotionally and physically.

Thermal burns, the most common type, typically result from residential fires, motor vehicle accidents, misused matches or lighters (such as a child playing with matches), improperly stored gasoline, space heater or electrical malfunctions, and arson. Other causes include improper handling of firecrackers, scalding accidents, and kitchen accidents (such as a child touching a hot stove).

Chemical burns result from the contact, ingestion, inhalation, or injection of acids, alkali, or vesicants. Electrical burns commonly occur after contact with faulty electrical wiring or high-voltage power lines, or when electric cords are chewed (by young children).

Radiation burns are caused by ionizing radiation and include sunburn and radiotherapy burns. Friction, or abrasion, burns happen when the skin is rubbed harshly against a coarse surface.

Burn severity is classified by depth of injury.

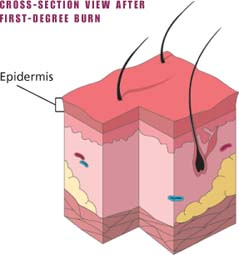

Superficial burns

Superficial burns, also referred to as first-degree burns, cause localized injury to the skin (epidermis only) by direct (such as a chemical spill) or indirect (such as sunlight) contact. The barrier function of the skin remains intact, and these burns aren’t life-threatening.

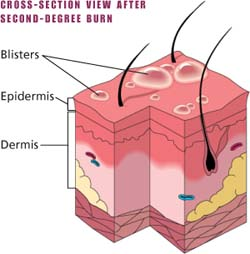

Superficial partial-thickness burns

Superficial partial-thickness burns, also referred to as second-degree burns, involve destruction to the epidermis and some dermis. Thin-walled, fluid-filled blisters develop within a few minutes of the injury along with mild to moderate edema and pain. As these blisters break, the nerve endings become exposed to the air. Because pain and tactile response remains intact, subsequent treatments are very painful. The barrier function of the skin is lost.

Deep partial-thickness burns

Deep partial-thickness burns are a more severe second-degree burn that extends deeper into the dermis. The skin appears mixed red or waxy white. Blisters aren’t usually present and edema usually develops. Sensation is decreased in the area of the burn.

Superficial partial-thickness burns

Superficial partial-thickness burnsPartial-thickness burns involve destruction to the epidermis and some dermis. Thin-walled, fluid-filled blisters develop within a few minutes of the injury along with mild to moderate edema and pain. As these blisters break, the nerve endings become exposed to the air. Pain and tactile responses remain intact, so subsequent treatments are painful. The barrier function of the skin is lost.

|

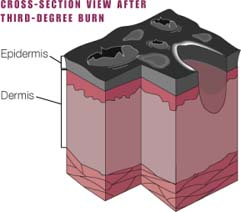

Full-thickness burns

Full-thickness burns, also referred to as third-degree burns, affect every body system and organ. A full-thickness burn extends through the epidermis and dermis into the subcutaneous tissue. Within hours, fluid and protein shift from capillary to interstitial spaces, causing edema. The immediate immunologic response to the burn injury makes burn wound sepsis a potential threat. Last, an increased calorie demand after the burn injury increases the metabolic rate.

Fourth-degree burns

Fourth-degree burns involve muscle, bone, and interstitial tissues.

Signs and symptoms

Superficial burn

Localized pain and erythema, usually without blisters in the first 24 hours, caused by injury from direct or indirect contact with a burn source

Chills, headache, localized edema, and nausea and vomiting (in more severe cases)

Superficial partial-thickness burn

Thin-walled, fluid-filled blisters appearing within minutes of the injury, with mild to moderate edema and pain

Deep partial-thickness burn

White, waxy or mixed red appearance to the damaged area

Decreased capillary refill and sensation

Full-thickness burn

White, brown, or black leathery tissue and visible thrombosed vessels due to destruction of skin elasticity (dorsum of the hand is the most common site of thrombosed veins), without blisters

Fourth-degree burn

Damage extends through deeply charred subcutaneous tissue to muscle and bone

Usually painless because nerve fibers are burned

Treatment

Immediate classification and estimation of extent or injury to guide treatment

Lactated Ringer’s solution through a large-bore I.V. line to expand vascular volume; volume of infusion calculated according to the extent of the area burned and the time that has elapsed since the burn injury occurred

Indwelling urinary catheter to permit accurate monitoring of urine output

I.V. morphine to alleviate pain and anxiety

Nasogastric (NG) tube to prevent gastric distention and accompanying ileus from hypovolemic shock

Booster of 0.5 ml of tetanus toxoid administered I.M.

Treatment of the burn wound

Initial debriding by washing the surface of the wound area with mild soap

Sharp debridement of loose tissue and blisters (blister fluid contains agents that reduce bactericidal activity and increase inflammatory response)

Partial-thickness wounds: covering with hydrogel, silicone-coated nylon, or other dressing

Fourth-degree wounds: covering the wound with an antimicrobial and a nonstick bulky dressing (after debridement)

Escharotomy, if the patient is at risk for vascular, circulatory, or respiratory compromise

Nursing considerations

For severe burns, provide immediate, aggressive treatment to increase the patient’s chance for survival. Make sure the patient with major or moderate burns has adequate airway, breathing, and circulation. If needed, assist with endotracheal intubation. Administer 100% oxygen, as ordered, and adjust the flow to maintain adequate gas exchange.

Provide sufficient I.V. fluids to maintain a urine output of 30 to 50 ml/hour; the output of a child who weighs less than 66 lb (29.9 kg) should be maintained at 1 ml/kg/hour.

Remove any clothing that’s still smoldering. If it continues to adhere to the patient’s skin, first soak it in saline solution. Also remove jewelry and other constricting items.

Cover the burns with a clean, dry, sterile bed sheet.

Never cover large burns with saline-soaked dressings, which can drastically lower body temperature.

Start I.V. therapy immediately to prevent hypovolemic shock and maintain cardiac output. Use lactated Ringer’s solution or a fluid replacement formula, as ordered. Closely monitor the patient’s intake and output.

Assist with the insertion of a central venous pressure line and additional arterial and I.V. lines (using venous cutdown, if necessary), as needed. Insert an indwelling urinary catheter as ordered.

Continue fluid therapy, as ordered, to combat fluid evaporation through the burn and the release of fluid into interstitial spaces (possibly resulting in hypovolemic shock).

Check the patient’s vital signs every 15 minutes. Maintain his core body temperature by covering him with a sterile blanket and exposing only small areas of his body at a time.

Monitor the patient for signs and symptoms of shock—altered level of consciousness, hypotension, and respiratory distress.

Insert an NG tube, as ordered, to decompress the stomach and avoid aspiration of stomach contents.

Provide a diet high in potassium, protein, vitamins, fats, nitrogen, and calories to keep the patient’s weight as close to his preburn weight as possible. If necessary, feed the patient through a feeding tube (as soon as bowel sounds return, if he has had paralytic ileus) until he can tolerate oral feeding. Weigh him every day at the same time.

If the patient is to be transferred to a specialized burn care unit, prepare the patient for transport by wrapping him in a sterile sheet and a blanket for warmth and elevating the burned extremity to decrease edema.

If the patient has only minor burns, immerse the burned area in cool saline solution (55° F [12.8° C]) or apply cool compresses, making sure he doesn’t develop hypothermia. Next, soak the wound in a mild antiseptic solution to clean it, and give ordered pain medication.

Debride the devitalized tissue. Cover the wound with an antibacterial agent and a nonstick bulky dressing, and administer tetanus prophylaxis, as ordered.

Explain all procedures to the patient before performing them. Speak calmly and clearly to help alleviate his anxiety.

Give the patient opportunities to voice his concerns, especially about altered body image. When possible, show the patient how his bodily functions are improving. If necessary, refer him for mental health counseling.

Administer pain medication as ordered and evaluate its effectiveness. Provide emotional support because burns can be very painful as well as disfiguring.

Teaching about burns

Teaching about burns

If the patient has only a minor burn, stress the importance of keeping his dressing dry and clean, elevating the burned extremity for the first 24 hours, taking analgesics as ordered, and returning for a wound check in 2 days.

For a patient with a moderate or major burn, discharge teaching involves the entire burn team. Teaching topics include wound management; signs and symptoms of complications; use of pressure dressings, exercises, and splints; and resocialization. Make sure the patient understands the treatment plan, including why it’s necessary and how it will help his recovery.

Explain to the patient that a home health nurse can assist with wound care. Provide the patient with information on available support systems.

Teach the patient signs and symptoms of infection and when to seek medical attention.

Give the patient written discharge instructions for later reference.

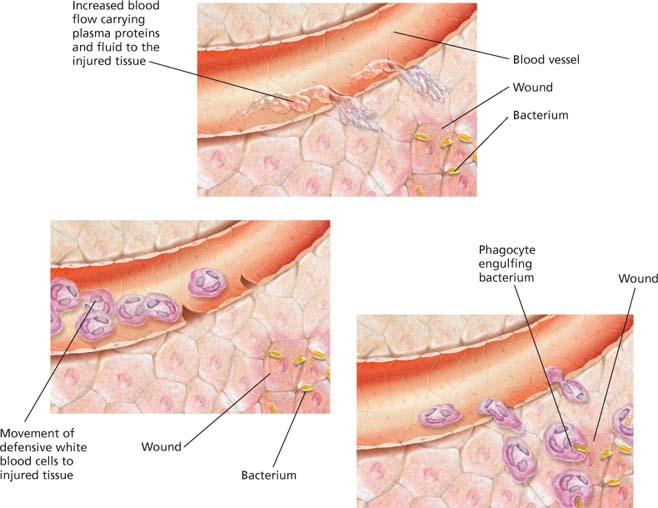

Cellulitis

An infection of the dermis or subcutaneous layer of the skin, cellulitis may follow damage to the skin, such as with a bite or a wound. If treated in a timely manner, the prognosis is usually good. If the cellulitis spreads, however, fever, erythema, and lymphangitis may occur, particularly in patients with other contributing health factors, such as diabetes, immunodeficiency, impaired circulation, or neuropathy.

Signs and symptoms

Erythema and edema

Pain at the site and, possibly, the surrounding area

Fever and warmth

Treatment

Antibiotics, either p.o. or I.V., for the causative organism, depending on the severity

Pain medication, as needed, to promote comfort

Elevation of the affected extremity above heart level to promote comfort and decrease edema

Modified bed rest

Nursing considerations

Assess the patient for an increase in size of the affected area or worsening pain.

Administer an antibiotic and an analgesic, and elevate the extremity as ordered.

Teaching about cellulitis

Teaching about cellulitis

Emphasize the importance of complying with treatment to prevent relapse.

Instruct the patient to use a properly cleaned shower instead of the bathtub until the skin problem has healed to prevent worsening of the infection.

To prevent recurring cellulitis, teach the patient to maintain good general hygiene and to carefully clean abrasions and cuts. Urge early treatment to prevent the spread of infection.

Describe the importance of range-of-motion exercises to prevent deep vein thrombosis.

Dermatitis

Dermatitis is characterized by inflammation of the skin and may be acute or chronic. It occurs in several forms, including contact, seborrheic, nummular, exfoliative, and stasis dermatitis.

Atopic dermatitis (discussed here), also commonly referred to as atopic or infantile eczema or Besnier’s prurigo, is a chronic inflammatory response typically associated with other atopic diseases, such as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chronic urticaria. It usually develops in infants and toddlers between ages 6 months and 2 years, commonly in those with strong family histories of atopic disease. These children typically acquire other atopic disorders as they grow older. In most cases, this form of dermatitis subsides spontaneously by age 3 and remains in remission until prepuberty (ages 10 to 12), when it flares up again. The disorder affects about 9 out of every 1,000 people.

Atopic dermatitis is exacerbated by certain irritants, infections (commonly Staphylococcus aureus), and allergens. Common allergens include pollen, wool, silk, fur, ointment, detergent, perfume, and certain foods, particularly wheat, milk, and eggs. Flare-ups may also occur in response to temperature extremes, humidity, sweating, and stress.

Types of dermatitis

| Type | Causes | Assessment findings | Diagnosis | Treatment and intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic dermatitis | ||||

| Characterized by inflammatory eruptions on the hands and feet |

|

|

|

|

| Contact dermatitis | ||||

| Commonly, sharply demarcated skin inflammation and irritation due to contact with concentrated substances to which the skin is sensitive, such as perfumes or chemicals |

|

|

|

|

| Exfoliative dermatitis | ||||

| Severe, chronic skin inflammation characterized by redness and widespread erythema and scaling |

|

|

|

|

| Seborrheic dermatitis | ||||

| An acute or subacute disease that affects the scalp, face and, occasionally, other areas and is characterized by lesions covered with yellow or brownish gray scales |

|

|

|

|

| Stasis dermatitis | ||||

| Condition usually caused by impaired circulation and characterized by eczema of the legs with edema, hyperpigmentation, and persistent inflammation |

|

|

|

|

Signs and symptoms

Intense itching

Erythematous patches in excessively dry areas at flexion points, such as the antecubital fossa, popliteal area, and neck; in children, may appear on the forehead, cheeks, and extensor surfaces of the arms and legs

Edema, scaling, and vesiculation because of scratching

Vesicles that may be pus-filled

With chronic disease, multiple areas of dry, scaly skin with white dermatographism, blanching, and lichenification

Treatment

Eliminating allergens and avoiding irritants, extreme temperature changes, and other precipitating factors

Systemic antihistamines, such as hydroxyzine hydrochloride and diphenhydramine, to relieve pruritus

Topical application of a corticosteroid cream to alleviate inflammation

Systemic corticosteroid therapy only during extreme exacerbations

Weak tar preparations and ultraviolet B light therapy to increase the thickness of the stratum corneum

Antibiotics to fight a bacterial infection; antifungals or antivirals to fight a fungal or viral infection

Nursing considerations

Help the patient schedule daily skin care. Keep his fingernails short to limit excoriation and secondary infections caused by scratching.

Be alert for possible adverse effects associated with corticosteroid use: sensitivity reactions, GI disturbances, musculoskeletal weakness, neurologic disturbances, and cushingoid symptoms.

To help clear lichenified skin, apply occlusive dressings, such as a plastic film, intermittently. This treatment requires a physician’s order and experience in dermatologic treatment.

Apply cool, moist compresses to relieve itching and burning.

Encourage the patient to verbalize feelings about his appearance, including embarrassment and fear of rejection. Offer him emotional support and reassurance and arrange for counseling, if necessary.

Teaching about dermatitis

Teaching about dermatitis

Provide written instructions for skin care and treatment with corticosteroids. Teach the patient and his family to recognize signs of corticosteroid overdose and to notify the physician immediately if they occur.

If the patient experiences an excessively dry mouth caused by antihistamine use, advise him to drink water or suck ice chips.

Warn that drowsiness is possible with the use of antihistamines to relieve daytime itching. If nocturnal itching interferes with sleep, suggest methods for inducing natural sleep, such as drinking a glass of warm milk, to prevent overuse of sedatives.

Advise the patient to wear loose cotton clothing to decrease itching.

Stress the importance of meticulous hand washing and good personal hygiene.

Caution the patient to avoid bathing in hot water because heat causes vasodilation, which induces pruritus.

Instruct the patient to use plain, tepid water (96° F [35.6° C]) with a nonfatty, nonperfumed soap but to avoid using any soap when lesions are acutely inflamed. Advise him to shampoo frequently and to apply corticosteroid solution to the scalp afterward. Suggest using a lubricating lotion after a bath.

With severe dermatitis, show the patient how to apply occlusive dressings. For example, severe contact dermatitis may require a topical corticosteroid and occlusion with gloves to increase drug absorption and skin hydration.

Teach the patient how to apply wet-to-dry dressings to soothe inflammation, itching, and burning; to remove crusting and scales from dry lesions; and to help dry up oozing lesions.

Help the patient to identify and avoid aggravating factors and allergens associated with atopic dermatitis.

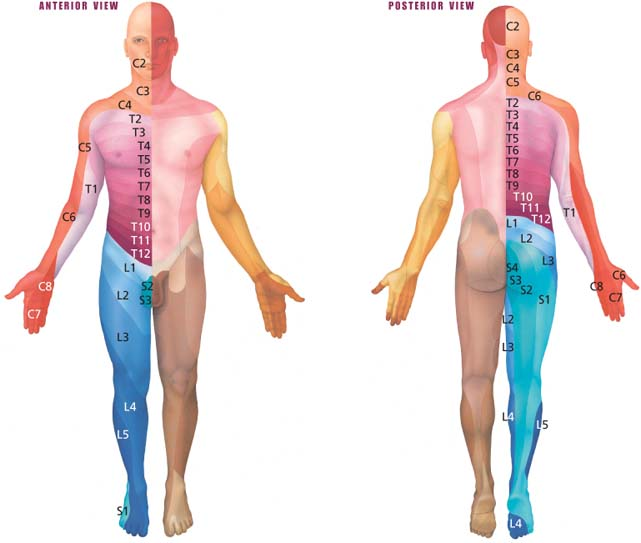

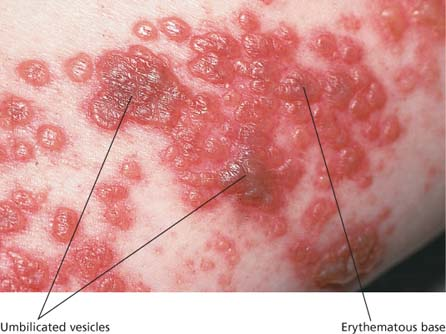

Herpes zoster

Herpes zoster, also called shingles, is an acute, unilateral and segmental inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia and is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (herpesvirus). It produces localized vesicular skin lesions confined to a dermatome, which may produce severe neuralgic pain in the areas bordering the inflamed nerve root ganglia.

The infection is found primarily in adults ages 50 to 70, and the prognosis is usually good, with most patients recovering completely, unless the infection spreads to the brain.

Herpes zoster is more severe in the immunocompromised patient but seldom is fatal. Patients who have received a bone marrow transplant are especially at risk for the infection.

Although the process is unclear, the disease seems to erupt when the virus reactivates after dormancy in the cerebral ganglia (extramedullary ganglia of the cranial nerves) or the ganglia of posterior nerve roots. The virus then may multiply as it reactivates, but antibodies remaining from the initial infection may neutralize it. Without opposition, however, the virus continues to multiply in the ganglia, destroys neurons, and spreads down the sensory nerves to the skin.

Herpes zoster is contagious until all the blisters are crusted over, but only for individuals who haven’t previously had chickenpox.

Signs and symptoms

Fever

Malaise

Burning or sensitive skin several days before rash appears

Pain that mimics appendicitis, pleurisy, musculoskeletal pain, or other conditions

After 2 to 4 days, severe, deep pain; pruritus; and paresthesia or hyperesthesia (usually affecting the trunk and, occasionally, the arms and legs)

Pain that may be intermittent, continuous, or debilitating, usually lasting from 1 to 4 weeks

Fluid-filled vesicles with an erythematous base on skin areas supplied by sensory nerves of a single or associated group of dorsal root ganglia (nerve pathways)

After about 10 days, dried vesicles that have formed scabs

Enlarged regional lymph nodes

With geniculate involvement, vesicles in the external auditory canal, ipsilateral facial palsy, hearing loss, dizziness, and loss of taste

With trigeminal involvement, eye pain, possible corneal and scleral damage, and impaired vision

Treatment

Oral acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), and valacyclovir (Valtrex) therapy to accelerate healing of lesions and resolution of zoster-associated pain

Antipruritics (such as calamine lotion) to relieve pruritus and analgesics (such as aspirin, acetaminophen or, possibly, codeine) to relieve neuralgic pain

Tricyclic antidepressants to help relieve neuritic pain

Systemic corticosteroids, such as cortisone or corticotropin, to reduce inflammation and the intractable pain of postherpetic neuralgia (other possible therapies: tranquilizers, sedatives, or tricyclic antidepressants with phenothiazines)

As a last resort for pain relief, transcutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation, patient-controlled analgesia, or a small dose of radiotherapy

Cool compresses and use of Burow’s or Domeboro solution

Nursing considerations

Administer topical therapies as directed. If the physician orders calamine, apply it liberally to the patient’s lesions. Avoid blotting contaminated swabs on unaffected skin areas. Be prepared to administer drying therapies, such as oxygen, if the patient has severe disseminated lesions. Use silver sulfadiazine, as ordered, to soften and debride infected lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

How acne develops

How acne develops

Comedones of acne

Comedones of acne

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma

Superficial burns

Superficial burns

Full-thickness burns

Full-thickness burns

Phases of acute inflammatory response

Phases of acute inflammatory response

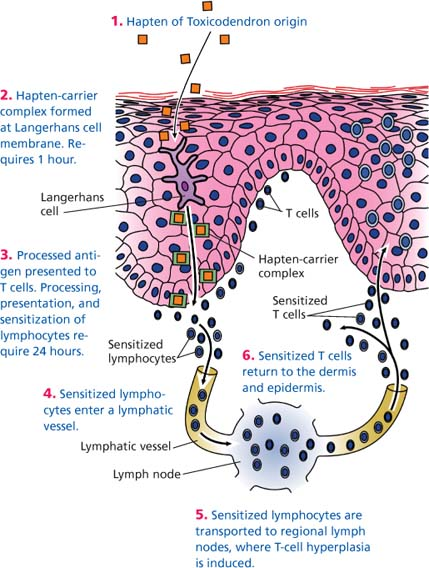

What happens in contact dermatitis

What happens in contact dermatitis