Incorporating the Core Competencies into Nursing Education

Introduction

The strategies for integrating quality care content and experiences into nursing education, for both academic programs and staff education, should be based on the five healthcare core competencies found in the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Health Professions Education (IOM, 2003b). All healthcare professions should meet these competencies:

Provide patient-centered care

Work in interprofessional teams

Employ evidence-based practice

Apply quality improvement

Utilize informatics

The IOM reports on quality include significant reforms (Tanner, 2003). There has been a shift to a competency-based approach to education for all healthcare professions. The core competencies identified are essential for healthcare professionals to respond effectively to patients’ care needs. “It is tempting to say we already do these things (five

core competencies). Surely we have been talking about informatics competencies for a long time, and we expect our graduates to be leaders and to work in interdisciplinary [interprofessional] teams. Nursing is, if nothing else, patient-centered. But the competencies advanced by IOM are deep and nuanced, based in evidence and clearly reflective of the major shifts in our patient population and their needs during the past decade. We have been talking about a revolution in nursing education for some time now. Our programs, although perhaps aged to perfection, may no longer be relevant, given the dramatic changes in health care. It is now time to work toward building one bridge over the quality chasm” (Tanner, 2003, p. 432).

core competencies). Surely we have been talking about informatics competencies for a long time, and we expect our graduates to be leaders and to work in interdisciplinary [interprofessional] teams. Nursing is, if nothing else, patient-centered. But the competencies advanced by IOM are deep and nuanced, based in evidence and clearly reflective of the major shifts in our patient population and their needs during the past decade. We have been talking about a revolution in nursing education for some time now. Our programs, although perhaps aged to perfection, may no longer be relevant, given the dramatic changes in health care. It is now time to work toward building one bridge over the quality chasm” (Tanner, 2003, p. 432).

The IOM first started publishing its critical reports on quality in 1999. Since then, what have we learned about the current status of quality in the healthcare delivery system? From 2007-2009, the system did not improve (Mullin, 2011). The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System evaluated the United States on 42 indicators related to quality, access, efficiency, equity, and healthy lives, all of which are directly related to the IOM reports on quality. The U.S. score was 64 out of a possible 100. What does this mean? At the first evaluation, in 2006, the score was 67; in 2008, it was 65. The United States is behind the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Germany in improvement of care. It ranked last in a list of 16 countries in number of deaths prevented by timely and effective medical care. Health system efficiency was scored at 53 out of a possible 100. Access to care has decreased. There were, however, some positive changes: for instance, the proportion of home care patients with improved mobility increased from 37% to 47% from 2004 to 2009. Providing the right care to prevent surgical complications improved from 71% in 2004 to 96% in 2009.

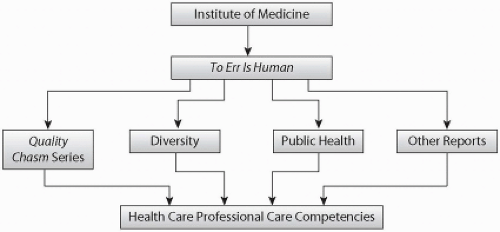

Figure 4-1 indicates the connection between the IOM reports in the Quality Chasm series and the core competencies. This part of the book discusses important care issues related to each of the five core competencies for healthcare professionals that you, as a student and professional nurse, need to consider.

Core Competency: Provide Patient-Centered Care

Identify, respect, and care about patients’ differences, values, preferences, and expressed needs; relieve pain and suffering; coordinate continuous care; listen to, clearly inform, communicate with, and educate patients; share decision-making and management; and continuously advocate disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles, including a focus on population health.

Patient-centered care (PCC) puts the focus on the patient and family instead of on the health professionals; for example, one approach to emphasize PCC in practice might be to have the health professionals come to the patient instead of moving the patient from room to room to see different specialists. All health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interprofessional team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics (IOM, 2003b). Nursing must adapt to the changing demographics of the patient population, integrate technologies, and meet critical competencies. The following content describes some of the issues related to patient-centered care.

Decentralized and Fragmented Care

You may have experienced fragmented care with your patients but may not have recognized it; if you do recognize it, you may often be frustrated by it. How did it feel when you first entered the healthcare setting as a student? Some common reactions are confusion, inability to understand what is going on, uncertainty as to who staff are and what the expectations are, unclear communication, and so on. Considering this experience can help you better appreciate what patients may be feeling. Many students worry about “drive-through health care.” When a test is delayed or postponed because someone did not order it, how does the patient feel and react, and what impact does this have on patient care when your well-planned schedule for care is no longer well planned? The goal is for you to better appreciate the trajectory or course of illness and the continuum of care.

Fragmented care exists throughout the healthcare system. Can you think of examples of fragmented care and practical solutions to solve them? Iatrogenic injury can be related to fragmented care. How might this occur in different healthcare settings, such as acute care, emergency room, ambulatory care, and home care?

What are the implications of decentralization and fragmentation on the nursing process? This discussion has two sides. Decentralization allows decision-making to be made closer to the patient and reinforces more autonomy at lower levels of an organization, but it can lead to variations in care from unit to unit and fragmentation of services. Consider how plans of care might ensure more decentralization and less fragmentation to improve safety. What might be the role of the nurse in that effort?

Changing Our Perspective of the Nursing Assessment

Assessment continues to be an important part of nursing care even while many other nursing activities change. The assessment should be a beginning point for patientcentered care and the first step in the therapeutic nurse-patient relationship (Jones, 2007). Consider how the assessment relates to patient-centered care and the role of data and communication in the care process. It is also important to emphasize that all healthcare professionals, not just nurses, assess patients. What do you know about these other assessments; how should you use that data? Do written assessments include repetitive questions? When there is repetition, is it appropriate? Consider how assessment puts the patient in the center.

Self-Management Support

Self-management support is “the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems, including regular assessment of progress and problems, goal setting, and problem-solving support” (IOM, 2003f, p. 52). Another term for self-management is self-care, though the IOM uses self-management. Self-management is particularly important in chronic illness, such as diabetes and asthma, and becomes even more complex when patients have multiple problems. Self-management is an appropriate means to assist patients with acute care problems to return to their usual daily functioning as soon as possible; it is also a critical component of care for patients with chronic illnesses. The IOM report Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Healthcare Quality (2003f) identified primarily medical problems as priority concerns. However, the first two priorities are broader in scope: care coordination and self-management. These are very important parts of nursing care, and with the added emphasis on them, nurses should be taking a greater lead in studying and developing self-management interventions for patients and families or significant others.

You should consider self-management for every patient you care for and include the patient and the patient’s family in the process. It is important to note the patient’s view on informing his or her family, what can be shared, and how family should participate.

Effective self-management support requires collaboration between the patient and all providers involved in the care. Families should also be involved in the process of care. “Healthcare systems can support effective self-management by providing care that builds patient and family skills and confidence, increases patient and family knowledge about the condition, increases provider’s knowledge of the needs and preferences of the patient, and supports the patient and family in the psychosocial, as well as medical, responses to the condition” (Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], 2008e). Even patients with acute illnesses can benefit from more effective self-management.

Patient Errors in Self-Management

Although self-management allows patients to be more independent, it can also lead to errors. How can we help patients avoid errors during self-management?

Patients at risk for self-management errors include those with multiple chronic problems using multiple medications, and elderly patients trying to practice self-management in their homes. You can help patients with self-management by knowing how to assist patients in using Medisets to administer their medication; how to monitor medication use by patients and caregivers; and how to teach patients and caregivers what to review when they receive their medications, such as drug name and dose. Consider how confusing multiple oral medications with complex administration schedules might be for patients, and if patients can open childproof lids and read small-print labels (e.g., arthritis, poor eyesight). How easy is it for a patient to make an error? What interventions can you use to educate patients and their families, prevent errors, and help them improve their self-management? Medication reconciliation, which is discussed later, is also highly relevant to self-management.

Disease Management and Patient-Centered Care

Disease management, which involves self-management, can help decrease complications, length of stay, and costs. Disease management involves care coordination (one of the major priority areas of care), interprofessional teamwork, and patient-centered care. Patients who can particularly benefit include those who are chronically critically ill. In Long’s controlled study (2008), patients on mechanical ventilation for 72 hours or more were included in the sample. Patients were monitored and received disease management interventions from an advanced practice nurse. This coordinated, patient-centered approach improved outcomes. Nurses in the program communicated effectively, showed commitment to good patient outcomes, and understood how to help the patient and family navigate the system.

Nurse or patient navigation is being used in some clinical settings to assist patients through their treatment trajectory to meet their health needs, as was mentioned earlier. The nurse navigator works with the patient and family to guide them through the complex healthcare system to ensure better outcomes. Clinical nurse leaders (CNLs) often serve in this role.

The goals of disease management are to improve quality of life, decrease disease progression, and reduce hospitalizations. A nurse call center typically provides services such as monitoring health status; giving patient education and advice; and sharing information from labs, physicians, and pharmacies. Chronic illnesses that are typically monitored include diabetes, heart disease and hypertension, asthma, cancer, depression, renal disease, low back pain, and obesity. Insurers typically develop disease management programs and use case management to control costs. Disease management and case management are also relevant to community health.

The Institute of Health Improvement (IHI) offers tools to support self-management at http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Tools/ToolkitforClinicians.aspx. These tools are great resources. Examples of the tools are: Quality Compass Benchmarks, Blood Pressure Visual Aid for Patients, Self-Management Support: Patient Planning Worksheet, My Shared Plan, and Group Visit Starter Kit.

Chronic Illness and Self-Management

The number of persons with chronic illnesses has increased, as well as the number of people with more than one chronic illness. Some data on chronic illness includes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011):

Each year, 7 out of 10 deaths among Americans are from chronic diseases. Heart disease, cancer, and stroke account for more than 50% of all deaths each year.

In 2005, 133 million Americans—almost one out of every two adults—had at least one chronic disease. Nearly half of Americans aged 20-74 have some type of chronic condition.

Obesity has become a major health concern. One in every three adults is obese, and almost one in five youth between the ages of 6 and 19 is obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile of the CDC growth chart).

About one fourth of people with chronic conditions have one or more daily activity limitations.

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability, with nearly 19 million Americans reporting activity limitations.

Diabetes continues to be the leading cause of kidney failure, nontraumatic lowerextremity amputations, and blindness among adults.

Why does the United States have these problems with chronic illness? One reason is that with the better treatment available today, people with chronic illnesses live longer; consequently, there are more of them. The United States must improve care provided for those with chronic illness. Many of the IOM priority areas of care, monitored annually in the National Healthcare Quality Report, are chronic illnesses.

Effective management of a chronic illness requires daily management of the illness, and also should include activities to improve health in general. To accomplish this, the person with chronic illness needs to have an understanding of the illness and interventions to achieve self-management. Self-management focuses on care of the body and management of the condition, adapting everyday activities and roles to the condition, and dealing with the emotions arising from having the condition. “Self-management support is the care and encouragement provided to people with chronic conditions to help them understand their central role in managing their illness, make informed decisions about care, and engage in healthy behaviors” (IHI, 2008e).

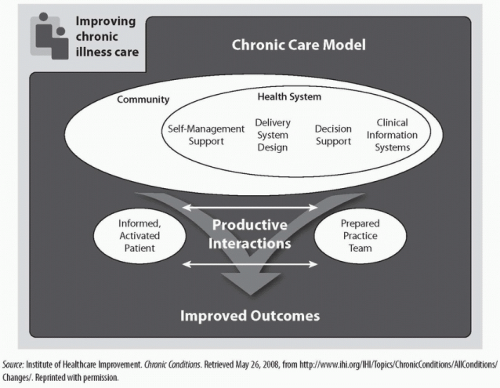

One approach is to use the Chronic Care Model, a patient-centered approach (Wagner, 1998; Improving Chronic Illness Care, 2003). The model emphasizes two principles:

The community should have resources and health policies that support care for chronic illnesses.

The health system should have healthcare organizations (HCOs) that support self-management, recognizing that the patient is the source of control

(patient-centered); a delivery system design that identifies clear roles for staff in relationship to chronic illness care; decision support with evidence-based guidelines integrated into daily practice; and clinical information systems to ensure rapid exchange of information and reminder and feedback systems.

This model is described in Figure 4-2, and at the web site of Improving Chronic Illness Care, http://www.improvingchroniccare.org. There are many links to content and application of the model to care issues, including an audiovisual presentation.

The Improving Chronic Illness Care organization is dedicated to assessing and developing strategies to improve chronic illness care in the United States, and to helping people with chronic illness to lead healthier, quality lives (Improving Chronic Illness Care, 2003). “Over 145 million people—almost half of all Americans—suffer from asthma, depression and other chronic conditions. Over eight percent of the U.S. population has been diagnosed with diabetes. Approximately one third of cases of diabetes are undiagnosed” (Improving Chronic Illness Care, 2011). According to the IOM reports, some of the major issues are:

Healthcare providers who do not have enough time to provide effective care;

Failure to implement established practice guidelines;

Lack of active follow-up to ensure the best outcomes; and

Patients inadequately trained in self-management (a priority area identified by IOM).

The following are some critical patient issues to consider when applying disease management to chronic illness:

Patients should understand basic information about their disease. (Even if the patient already has this information, students should confirm with patients and be prepared to share this information if requested.)

Understand the importance of self-management and development of skills required to effectively self-manage care.

Recognize the need for ongoing support from members of the practice team, family, friends, and community.

Self-Management and Diversity

How do cultural issues affect self-management? How is the community involved? When providing care in the community, chronic illness is important, as this is where most of the prevention of chronic illness and care for chronic illness occur. Patients from different ethnic groups may respond to chronic illness and to self-management differently. Language affects patients’ abilities to understand directions, which is critical to effective self-management. Family roles vary in different cultures, which can influence how families respond and the roles they may or may not assume. Health literacy (discussed later) is a critical factor in ensuring quality care in any diversity situation.

Diversity and Disparities in Health Care

Diversity and disparities in health care are critical components of patient-centered care—affecting patient needs and responses, communication, quality, and outcomes throughout the continuum of care. The following content relates to this critical topic.

Safety-Net Hospitals

Safety-net hospitals treat poor and underserved patients. Medicaid often reimburses for this care, but many patients may have no way to pay for their care (Reinberg, 2008). Data collected between 2004 and 2006 from 3,665 safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals revealed that the quality of care at safety-net hospitals is below the level of other hospitals (Werner, Goldman, & Dudley, 2008). The results relate directly to healthcare disparities. What do you need to know about the safety-net system and the needs of vulnerable populations?

These hospitals rely on state and federal funding from Medicaid and other sources. Most are inner-city and teaching hospitals and do not have the funds to improve the quality of care at the same rate as other hospitals. Ironically, though, these hospitals may not receive funding to improve because such funding is often performance-based.

Hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are the hospitals that serve a larger proportion of low-income patients, such as those on Medicaid, and uninsured patients. Though healthcare reform should help reduce this problem, provisions of the current healthcare reform legislation dealing with this issue do not go into effect until 2014.

Hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are the hospitals that serve a larger proportion of low-income patients, such as those on Medicaid, and uninsured patients. Though healthcare reform should help reduce this problem, provisions of the current healthcare reform legislation dealing with this issue do not go into effect until 2014.

Quality ratings at hospitals that are described as safety-net hospitals have been variable. McHugh, Kang, and Hasnain-Wynia (2009) note in their study that one has to be careful and consider the criteria used to classify a hospital as a safety-net hospital: “Public or teaching hospitals had lower performance scores on four ‘process of care’ measures than did private, nonteaching hospitals, but results were mixed for safety-net hospitals identified by the level of uncompensated care they provide.” This is a topic that you can explore and then discuss as to its impact on quality care and on nursing.

Reaction to the Shifting Demographics of the Patient Population

Americans are older than ever, living with multiple comorbidities and chronic health needs. The other end of the life span is also at increasing risk, with a population of children who before the age of 10 are experiencing comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity; furthermore, many women are delaying childbearing well into their forties, which may lead to complications during pregnancy and for the newborn. These demographics indicate that long-term health care will require a delivery system capable of handling this growing complexity. Because these are major shifts from the patient pool of the past, healthcare professionals need education that prepares them to intervene in complex health problems in a more efficient, safer way to reach quality outcomes that are also cost-effective.

At the same time, the population is becoming more diverse. Understanding cultural beliefs and values and their relationship are part of developing cultural competence. Understanding the demographics and cultural backgrounds of your patients, and addressing them in patient care plans, is an important part of providing care to diverse populations.

For example, examine the study by Li, Glance, Yin, and Mukamel (2011). This study considers the impact of racial disparities on rehospitalization among Medicare patients in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). There was a difference in readmission rates between White patients and Black patients (rehospitalization at 30 days was 14.3% for White patients and 18.6% for Black patients; at 90 days it was 22.1% for White patients and 29.5% for Black patients). The researchers commented that the SNFs that had more Black patients tended to have fewer resources. How might their data relate to safetynet hospitals?

Emergency Care and Diversity and Disparities

Emergency care is a critical concern in the United States, as noted in three IOM reports from 2007 discussed in Part 1. A common assumption is that we have this problem

because so many uninsured persons use the emergency department (ED) when they do not need urgent care. Actually, this is not correct. The uninsured do not come to the ED for a bad cold, because they have to pay for this care; in contrast, someone with insurance coverage has to pay only a copayment for this service (Carmichael, 2008). Carmichael (2008) notes that 17% of people are uninsured, but they account for only 10% to 15% of ED visits. From 2008-2009, though, there was an increase in use of emergency departments (EDs) by the uninsured. However, diversity issues are prevalent in emergency care, and the need for quick, effective communication with patients and families is critical. Accessibility of interpreters is often a barrier in the emergency care delivery system.

because so many uninsured persons use the emergency department (ED) when they do not need urgent care. Actually, this is not correct. The uninsured do not come to the ED for a bad cold, because they have to pay for this care; in contrast, someone with insurance coverage has to pay only a copayment for this service (Carmichael, 2008). Carmichael (2008) notes that 17% of people are uninsured, but they account for only 10% to 15% of ED visits. From 2008-2009, though, there was an increase in use of emergency departments (EDs) by the uninsured. However, diversity issues are prevalent in emergency care, and the need for quick, effective communication with patients and families is critical. Accessibility of interpreters is often a barrier in the emergency care delivery system.

“Emergency departments have the only legal mandate in the U.S. healthcare system to provide health care according to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). This law ensures that anyone who comes to an emergency department, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay, must receive a medical screening exam and be stabilized. According to a 2009 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) survey on the U.S. financial crisis, 66 percent of emergency physicians polled have seen an increase of uninsured patients in their emergency departments during the current financial crisis” (ACEP, 2011).

Patients with nonurgent medical conditions may wait longer for care, but once seen, they are treated quickly and released. “Dangerous overcrowding is caused when a lack of hospital resources results in acutely ill patients being ‘boarded’ in an emergency department because no hospital inpatient beds are available, and ambulances must be diverted to other hospitals. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified only 12.1 percent of hospital emergency department visits as nonurgent in 2006” (ACEP, 2011). The IOM reports on emergency services are described in Part 1.

Clinical Trials and Disparities

The current design and administration of clinical trials in the United States underrepresents certain populations (Mozes, 2008). Participation in clinical studies among African Americans, Hispanics, and older Americans is disproportionately low. Mozes’s study indicates that the disparities are largely due to reliance on strict sample inclusion or exclusion criteria, the use of lengthy and complicated consent forms available only in English, and a lack of specific information on cost reimbursement for participants. These disparities can skew treatment recommendations based on studies with inequitable representation in their samples. We need to expand clinical trial participation so research results can better reflect all populations.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) includes consideration of diversity (Wessling, 2008). Because many studies do not include racially diverse participants, it is critical to consider similarities or differences in populations when reviewing evidence, to better ensure effective EBP.

Disparities in Rural Areas

Typically, care for people who live in rural areas is covered in community health content. The rural population often includes multiple ethnic groups, but the rural population as a whole also experiences disparities in health care (Healthy People 2020; South Carolina Rural Health Research Center, 2009):

In rural areas, poverty rates are two to three times higher for minorities than for Whites.

13% of rural whites are poor, compared to 34% of African Americans, 25% of Hispanics, and 34% of Native Americans in rural environments.

Rural residents are less likely than urban residents to receive preventive health services, and rural Hispanics are significantly less likely than rural non-Hispanic Whites to report receiving preventive medical services.

20% of nonmetropolitan counties lack mental health services, compared to 5% of metropolitan counties.

There are 2,157 health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) in rural America, compared to 910 in urban areas.

Three out of four rural minorities live in HPSAs, versus three out of five rural Whites.

About 20% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, but only 10% of physicians practice in rural America.

Much more must be done to improve care in rural areas. The National Rural Health Association provides important current information on this topic (http://www.ruralhealthweb.org/go/left/about-rural-health/what-s-different-about-rural-health-care).

Diversity and The Joint Commission

The Joint Commission published a practical guide that healthcare organizations can use to develop and improve programs and services that accommodate the needs of diverse populations (Joint Commission, 2008). The recommendations of this report include:

Build a leadership-driven foundation to establish specific organization-wide policies and procedures for better meeting patients’ diverse cultural and language needs.

Collect and use data to assess community and patient needs and improve current cultural and language services (such as interpreter services, spiritual services, and dietary services).

Accommodate the needs of specific populations through a continuous process of targeting culturally competent initiatives to those needs; include staff training and education, patient education, and other strategies that help patients better manage their care.

Establish internal and external collaborations with the local community to share information and resources that meet the needs of diverse patients.

The report is available online, along with other Joint Commission resources on diverse patient populations, at http://www.jointcommission.org/Advancing_Effective_Communication/

Workforce Diversity

National League for Nursing (NLN) data for 2005-2006 (March 3, 2008) indicate that the percentage of graduating prelicensed students who are members of racial or ethnic minority groups increased from 2008 to 2009 (NLN, 2009). There was also an increase in the percentage of men. This is good news, but much more remains to be done regarding workforce diversity. An increasing number of grant opportunities are aimed at increasing the mix of ethnic groups among nurses so they can provide more culturally sensitive, appropriate care. Data about the nursing workforce also indicate more diversity. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) reports that in 2008, 16.8% of nurses were Asian, Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, and/or Hispanic, which is an increase from 12.2% in 2004 (HRSA, 2010).

The National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR)

As mentioned in Part 1, there is a pressing need to monitor healthcare disparities (IOM, 2002). Since 2003, the AHRQ has prepared the NHDR. The annual report analyzes racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities in health care. The IOM recommendations for this annual report include (IOM, 2002, p. 7):

Analyze racial and ethnic disparities, considering socioeconomic status;

Conduct research to determine how to best measure socioeconomic status as it relates to healthcare access, service use, and quality;

Recognize that access is a critical element of healthcare quality;

Measure high and low use of certain healthcare services; include data state by state;

Work with public and private organizations that provide data to increase standardization; and

Provide AHRQ with resources to compile an annual survey of disparity in health care, the NHDR.

The 2010 report (reports are several years behind current date) focused on three questions (AHRQ, 2010a, 2010b):

What is the status of healthcare quality and disparities in the United States?

How have healthcare quality and disparities changed over time?

Where is the need to improve healthcare quality and reduce disparities greatest?

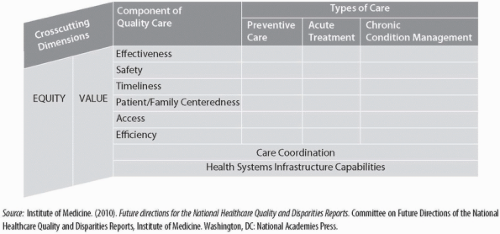

Figure 4-3 describes the most current matrix for the report. The matrix has changed since the first IOM report on disparities, which was described in Part 1. The annual report matrix provides an excellent tool for students to understand the issues and to use the annual report data. The annual report is available at www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr10.htm.

Cultural Competence

“The process of developing cultural competence is a means of responding effectively to the huge ethnic and racial demographic shifts and changes that are confronting our country’s healthcare system. Cultural competence is a defined set of policies, behaviors, attitudes, and practices that enable individuals and organizations to work effectively in cross-cultural situations. Cultural competence is the ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviors, including the tailoring of delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs” (Salisbury & Byrd, 2006, p. 90). The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) strongly supports teaching cultural competence in baccalaureate education, as stated in The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice (AACN, 2008b)—a viewpoint that clearly derives from the IOM reports on diversity and healthcare disparities. Another definition of cultural competence is the “attitudes, knowledge, and skills necessary for providing quality care to diverse populations” (California Endowment, 2003, as cited in AACN, 2008b, p. 1). The Essentials of Masters Education in Nursing also emphasizes the need for cultural competence in its Essential VIII, which “recognizes that the master’s-prepared nurse applies and integrates broad, organizational, client-centered, and culturally appropriate concepts in the planning, delivery, management, and evaluation of evidence-based clinical prevention and population care and services to individuals, families, and aggregates/identified populations” (AACN, 2011, p. 5).

Cultural competence must be integrated in the curriculum. This perspective is based on the following assumptions (AACN, 2008b, pp. 2-3; Paasche-Orlow, 2004):

Liberal education for nurses provides a foundation of intellectual skills and capacities for learning and working with diverse populations and contexts.

Faculty with requisite attitudes, knowledge, and skills can develop relevant culturally diverse learning experiences.

Development of cultural competence in students and faculty occurs best in environments supportive of diversity and facilitated by guided experiences with diversity.

Cultural competence is grounded in the appreciation of the profound influence of culture in people’s lives, and the commitment to minimize the negative responses of healthcare providers to these differences.

Cultural competence results in improved measurable outcomes, which includes the perspectives of those served.

A paper from AACN (2008a) describes background and content that should be considered in baccalaureate programs to facilitate cultural competence. This document complements Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice (AACN, 2008b).

The AACN cultural competence toolkit (www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/toolkit.pdf) identifies five competencies for culturally competent care, and content recommendations. The competencies are (2008a, pp. 2-3):

Apply knowledge of social and cultural factors that affect nursing and health care across multiple contexts.

Use relevant data sources and best evidence in providing culturally competent care.

Promote achievement of safe and quality outcomes of care for diverse populations.

Advocate for social justice, including commitment to the health of vulnerable populations and the elimination of health disparities.

Participate in continuous cultural competent development.

Consider how you currently meet these competencies.

Campinha-Bacote (2003) developed a cultural competence assessment tool in versions for students and staff. It is based on Campinha-Bacote’s volcano model of the process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services, which defines cultural competence as “the process in which the healthcare professional continually strives to achieve the ability and availability to effectively work within the cultural context of a client” (Campinha-Bacote, 2008). It is a process of becoming culturally competent, not being culturally competent. Campinha-Bacote’s model of cultural competence views cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, cultural encounters, and cultural desire as the five constructs of cultural competence. The five constructs are:

Cultural awareness, defined as the process of conducting a self-examination of one’s own biases toward other cultures and the in-depth exploration of one’s cultural and professional background. Cultural awareness also involves being aware of the existence of documented racism and other “isms” in healthcare delivery.

Cultural knowledge, defined as the process in which the healthcare professional seeks and obtains a sound information base regarding the worldviews of different cultural and ethnic groups, as well as biological variations, diseases and health conditions, and variations in drug metabolism found among ethnic groups (biocultural ecology).

Cultural skill, the ability to conduct a cultural assessment to collect relevant cultural data regarding the client’s presenting problem, and to accurately conduct a culturally based physical assessment.

Cultural encounters, the process that encourages the healthcare professional to directly engage in face-to-face cultural interactions and other types of encounters with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds in order to modify existing beliefs about a cultural group and to prevent possible stereotyping.

Cultural desire, the motivation of the healthcare professional to “want to”—rather than “have to”—engage in the process of becoming culturally aware, culturally knowledgeable, and culturally skillful and to seek cultural encounters. Cultural desire is the spiritual and pivotal construct of cultural competence that provides the energy source and foundation for the healthcare professional’s journey toward cultural competence. This model views cultural competence as a volcano, which symbolically represents cultural desire as stimulating the process of cultural competence. When cultural desire erupts, it powers entry into the process of becoming culturally competent by genuinely seeking cultural encounters, obtaining cultural knowledge, conducting culturally sensitive assessments, and being humble in the process of cultural awareness.

Summary of Diversity and Disparity Issues

Disparities can be a difficult topic for faculty and students. Healthcare providers view themselves as caring people who are open. “Discourse on provider bias has been silent in healthcare literature. Medicine and nursing as predominantly White professions have failed to acknowledge the White domination inherent in and perpetuated by its research, clinical, and educational practices” (Byrne, 2000; Feagin & Vera, 1995, as cited in Baldwin, 2003, p. 8). You need opportunities to discuss these issues in a safe environment—one in which your opinions will not be negatively criticized, but rather will be used to develop professional attitudes and behaviors. For example, you need to understand that many patients mistrust the healthcare system because they have experienced bias from healthcare providers in the past, which affects future encounters. Communication is a critical element, and health literacy also plays a major role in disparities. (Information about health literacy is covered in this section.) Cultural competence is also highly personal. Take some time to consider your own cultural background and how it influences you personally and might influence your practice.

Healthcare Literacy

Healthcare literacy is “the ability to read, understand, and act on healthcare information” (IOM, 2004a, p. 52). Health literacy should be carefully considered in the creation

and use of teaching materials for patients and families. In particular, because you teach patients, you need to learn how to assess patient understanding and to make changes as required. There are many examples of medical forms and brochures that are supposed to provide patients with information, but the information is not always so easy to understand, even for people whose first language is English!

and use of teaching materials for patients and families. In particular, because you teach patients, you need to learn how to assess patient understanding and to make changes as required. There are many examples of medical forms and brochures that are supposed to provide patients with information, but the information is not always so easy to understand, even for people whose first language is English!

As noted in the National Assessment of Adult Literacy in the United States, 14% of the population is at the basic literacy level, with 29% below basic, and the ability to use numbers is even lower (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003). Five percent are not literate in English. With the increasing number of immigrants, the percentage is likely to increase in many areas of the country.

An investigation of the relationship between health literacy and adherence to clinical outcomes reviewed 44 studies (DeWalt et al., 2004). Some of the findings from this review are:

People who have low literacy are 1.5 to 3 times more likely to have adverse outcomes than those with higher literacy.

Medicare enrollees with lower literacy have a greater chance of never having a Pap smear, not getting a mammogram within the past two years, and not receiving influenza and pneumococcal immunizations than those with higher health literacy.

Lower literacy is associated with increased risk for hospitalization.

Health illiteracy is more common in vulnerable populations such as low-income or racial and ethnic minorities (Ferguson, 2008). Women influence the health of children because they are mostly the caregivers. If women’s health literacy is low, this puts these women’s children at risk. Pregnant women who do not understand health information can affect the fetus and the infant’s health and development after birth (Puchner, 1995; Ferguson, 2008). The major barriers to quality health care associated with health literacy are inabilities to access care, manage illness, and process information (DeWalt & Pignone, 2008).

Accessing care: Critical issues are obtaining health insurance; finding healthcare providers; and knowing when to seek health care. For example, finding contact information, making appointments, and keeping a record of appointments may all be difficult for someone who cannot read or write.

Managing illness: Managing illness today, whether acute or chronic illness, can be complex; it may involve complicated prescription recommendations, testing schedules, and appointments with different providers at different places. Patients need to know the right questions to ask, as information is often not freely shared. Healthcare transitions (handoffs) are very common; patients move from provider to provider even within the same healthcare organization, increasing the risk of errors and also requiring the patient to adapt to changes and new providers. (Handoffs are discussed later in the content about the quality improvement core competency.)

Processing information: Patients are presented with informed consents and other documents, often written in a manner they cannot understand, especially under stressful situations. Family members can be very helpful with this type of information. Medical bills can easily overwhelm someone even if the person reads English well; for those who do not, the inability to read and comprehend bills can lead to major problems and stress.

Patient advocacy can make a major difference in helping patients and families who are experiencing health literacy problems. One of the goals of Healthy People 2020 is to improve consumer health literacy. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also made changes to regulate drug information and improve health literacy. Limited health literacy leads to higher outpatient medication errors, possible complications, increased costs, and inability to reach positive outcomes.

“The Joint Commission’s accreditation standards underscore the fundamental right and need for patients to receive information—both orally and written—about their care in a way in which they can understand this information” (Joint Commission, 2007, p. 5). Some of the means to improve health literacy identified by The Joint Commission are:

Create patient-centered environments where the patient is involved in decisionmaking and safety processes;

Increase awareness and understanding of health literacy;

Ensure that interpreters are available when needed;

Develop cultural competence;

Understand how communication affects quality care;

Teach consumers how to better access the care they need;

Review and improve informed consent materials and processes;

Use a disease management approach to better individualize care and reduce errors;

Standardize handoffs; and

Give patients clear information.

Health Literacy and Self-Management

Self-management will not be effective if the patient has a low level of health literacy. Why would this be so? What skills do patients need to manage their diabetes or arthritis? Consider how health literacy problems might relate to adult health, pediatrics, mental health, obstetrics, and community/public health. Nurses need to understand that health literacy issues can arise in all types of situations and can have an important impact on care and outcomes.

What does health literacy mean to you? How does your view of health literacy compare to the definition of health literacy used in the IOM report? Try to imagine the stigma that health-illiterate patients may feel.

Interpreters

Have you ever worked with an interpreter to facilitate communication with a patient? It can be a frustrating experience trying to communicate through a third party. This communication is different: You should speak directly to the patient, even though the natural tendency is to speak to the interpreter. What might be the advantages and disadvantages of depending on family members as interpreters? What might be the impact of a culture in which the husband makes decisions? Would the wife feel comfortable expressing herself, and would the husband try to soften difficult messages? Would it be better to use a native speaker or a language expert to interpret? There are options if no interpreter is available: finding a healthcare provider who speaks the language, working with community groups to help interpret, preparing visual materials that might aid communication, and so on.

Health Literacy and Health Education

It is important to connect health literacy with health education. Review consent forms, admission forms, and patient rights information, and assess your own ability to understand those forms and documents. What might interfere with patients’ reading and understanding what they have read? What would help them understand the documents better? You have some healthcare background, but what about patients and families who have none? During clinical experiences, how might health literacy affect your teaching of specific assigned patients? When you develop health education plans for individual patients, families, caregivers, or groups, consider assessment of health literacy issues in the assignment. Make sure this assessment is included in the plan of care.

Health Literacy and the Healthcare Delivery System

What is done in a specific healthcare organization to address health literacy? How do health agencies used for clinical experiences respond to health literacy in their patient information and education programs? You can gather information by observation, interviewing staff, and reviewing written materials and other types of educational materials (such as videos that might be shown to patients). Are interpreters available, and are they used? Is hearing-impaired equipment accessible, and is it used? Look at signs and their effectiveness (for example, the use of color to direct patients). What could be improved, and how could the environment be changed so that all patients can be understood and can better understand healthcare providers?

Health Literacy, Nursing Assessment, and Interventions

You can assess health literacy levels with a population group in their community or an agency and its patients, identifying problems and interventions that might have been taken and outcomes, and consider other types of interventions that might improve health literacy. Health literacy should be part of individual patient assessments. Is health literacy included in your patient assessments? If not, how could it be included? How should this assessment be done? Is it part of a healthcare organization’s standard assessment forms? Compare assessment forms from different healthcare organizations or different services within an organization.

What is the best way to assess patient health literacy? The typical response would be to identify years of school completed or birth location. However, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), a standardized tool that takes only five minutes to administer, is a more effective method (Baker, 2007).

Pain Management

Pain is a major healthcare problem, with 116 million adults in the United States experiencing common chronic pain conditions, at a conservatively estimated annual cost of $560 to $635 billion (IOM, 2011h). “Pain can be conceptualized as a public health challenge for a number of important reasons having to do with prevalence, seriousness, disparities, vulnerable populations, the utility of population health strategies, and the importance of prevention at both the population and individual levels” (IOM, 2011h, p. 55). In addition, Healthy People 2020 includes an objective related to pain: Increase the safe and effective treatment of pain. Health literacy is related to pain management. “Problems with understanding medication instructions contribute to the estimated 1.5 million preventable adverse drug events that occur each year” (IOM, 2011h, p. 66). There are also disparities in who receives effective treatment for pain, as discussed in the IOM reports on pain management. Patient education is a critical intervention, and one that directly involves nurses. The IOM notes the important roles that nurses have in providing care for patients with pain, describing pain management as an essential responsibility of nurses. Nurses can also be involved in research to improve care for pain, particularly interprofessional research.

The IOM identified pain management as a critical part of patient-centered care, and published a report on pain (2011h) as discussed in Part 1. This IOM report is an excellent resource for students, providing background information on pain as well as viewing pain as a public health challenge. The report describes the picture of pain, identifying the many different types of people with pain in an excellent figure (IOM, 2011h, Figure 1-1; the report is accessible at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Relieving-Pain-in-America-A-Blueprint-for-Transforming-Prevention-Care-Education-Research.aspx). The report makes several recommendations:

Recommendation 3.1. Promote and enable self-management of pain.

Recommendation 3.2. Develop strategies for reducing barriers to pain care.

Recommendation 3.3. Provide education opportunities in pain assessment and treatment in primary care.

Recommendation 3.4. Support collaboration between pain specialists and primary care clinicians, including referral to pain centers when appropriate.

Recommendation 3.5. Revise reimbursement policies to foster coordinated and evidence-based pain care.

Recommendation 3.6. Provide consistent and complete pain assessments.

How might these recommendations apply to the care you provide?

End-of-Life and Palliative Care

End-of-life and palliative care are two topics that have been added to the nursing curricula. The IOM includes these topics in its description of patient-centered care, and published a report called Improving Palliative Care for Cancer: Summary and Recommendations (2003c). This report is a good resource for students. According to this IOM report, the healthcare system continues to underrecognize, underdiagnose, and undertreat patients who experience significant suffering from their illness. “Palliative care focuses on addressing the control of pain and other symptoms, as well as psychological, social, and spiritual distress. Six major skill sets comprise complete palliative care” (IOM, 2003c, p. 3):

Communication

Decision-making

Management of complications of treatment and the disease

Symptom control

Psychosocial care of the dying

Care of the dying

You need to have an understanding of these important aspects of care, the barriers to providing effective care, and interventions that can assist patients and families. You also should experience an open dialogue about provider aspects of responses to patients who require this care.

Consumer Perspectives

Staying healthy, getting better, living with illness or disability, and coping with the end of life represent the consumer dimension described in the IOM report on the need to monitor healthcare quality (IOM, 2003f). They are also important parts of nursing care. The consumer perspective may help you to remember these elements when working with patients and their families. Explore what each of the components of the quality framework (discussed in more detail in the quality improvement core competency section in this part) really means in practice. What do these elements mean to a person with diabetes, mental illness, or breast cancer, or to a family with a newborn? These perspectives can help you to develop a better appreciation of patient-centered care when you are working with individuals, families, or groups in a variety of healthcare settings and in the community.

Privacy, Confidentiality, HIPAA

The topics of privacy, confidentiality, and HIPAA relate to patient-centered care. The critical issue is that the patient makes decisions about his or her health care. Healthcare providers share their expertise and recommendations, but do not make the decisions; a patient may decide to defer to the healthcare professional, but it should never be assumed that the patient will do so. You also need to clearly understand all aspects of patient information use and sharing. For example, you understand the ramifications of

electronic communication that you may be involved in, such as taking photos with cell phones while in clinical areas and then sharing them through social media networks, as well as discussing with friends on Facebook, Twitter, and the like about patients you have cared for in enough detail that the agency, patient, and/or staff could be identified. This same issue applies to electronic (and other) communication throughout the healthcare delivery system in public places.

electronic communication that you may be involved in, such as taking photos with cell phones while in clinical areas and then sharing them through social media networks, as well as discussing with friends on Facebook, Twitter, and the like about patients you have cared for in enough detail that the agency, patient, and/or staff could be identified. This same issue applies to electronic (and other) communication throughout the healthcare delivery system in public places.

Patient Advocacy

“There is a growing appreciation of the centrality of patient involvement as a contributor to positive healthcare outcomes and as a catalyst for change in healthcare delivery” (IOM, 2007e, p. 25). It is difficult to discuss patient-centered care without considering patient advocacy. A patient advocate is “the patient navigator, both in its aim to help and guide patients to make well-informed decisions about their health for the best outcomes and in its quest to create more effective systems and policies” (Earp, French, & Gilkey, 2008, p. xv). Earlier sections discussed some of the critical characteristics of patient-centered care as described by the IOM. Gerteis, Edgman-Levitan, Daley, and Delbanco (1993) describe dimensions of patient-centered care (which correlate with the IOM perspectives) as:

Respect for patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs

Coordination and integration of care among providers and healthcare institutions

Information, communication, and education tailored to patients’ needs

Physical comfort, especially freedom from pain

Emotional support to reduce the fear and worry associated with illness and treatment

Involvement of family and friends in caregiving and decision-making

Planning for transition and continuity to ensure that patients continue to heal after they leave the hospital

The three overarching goals of patient advocacy are patient-centered care, safer medical systems, and increased patient involvement (Gilkey, Earp, & French, 2008). Safety, as highlighted in the IOM reports, is critical, and there is greater need to bring the patient into the safety process (as discussed further regarding the quality improvement core competency). All three patient advocacy goals are related, and patient involvement is necessary for success of advocacy.

Patients have not always been welcomed into the healthcare process. Patients need to be partners in their own care; they have important information to share and must be involved in the decisions. Patient-provider communication plays a key role in meeting all three goals of patient advocacy. Patient advocacy can be described as a continuum (Gilkey, Earp, & French, 2008).

The individual level, which is the central level, emphasizes informing patients. The more patients know about their health and illness, the better they can participate in their care decisions and care.

The interpersonal level supports and empowers patients by connecting them with people who can help them and from whom they can get information. Patientprovider information is important at this level, where providers are concerned not only with biological but also with psychosocial issues and social, cultural, and financial factors that influence health and needs. Family and friends are also important.

The organizational and community level, which transforms the healthcare culture as to where, when, and how care is delivered.

The last is the policy level, where the consumer’s voice is translated into policy and law to ensure that patient advocacy is maintained.

The key strategies to meet the three patient advocacy goals are as follows (Earp, French, & Gilkey, 2008, pp. v-vii):

Understanding what patients are doing now and what providers can do to support them

Improving providers’ ability to communicate and create relationships

Transforming hospital and medical school culture (and nursing schools) to support patient- and family-centered care

Nursing should be part of this strategy, particularly this last item. Nurses describe themselves as patient advocates, but in this major publication on patient advocacy there were no nurse authors, and nursing is mentioned only in the beginning of the book. The book is based on a large conference on patient advocacy that was held in 2003 and 2005; it is notable that nursing did not have a leadership role.

Making consumers’ voices heard in policy and law

Patient Etiquette: How Does This Relate to Patient-Centered Care?

Patient etiquette may seem like a strange topic, but it is relevant to patient-centered care. Kahn (2008) discusses the need for etiquette-based medicine, but it seems to get lost in quite a few nursing education programs and experiences. Patients must be treated with respect, but we know that this does not always happen automatically or naturally. Viewing nurses as respectful of patients is also part of the nursing profession’s image. Patient etiquette includes items such as asking permission to enter the patient’s room and waiting for an answer; introducing yourself, shaking hands if appropriate, sitting down, and smiling as appropriate; briefly explaining your role on the team, or asking patients how they are feeling and how they feel about their illness and the care they have received. This would “[p]ut professionalism and patient satisfaction at the center of the clinical encounter and bring back some of the elements of ritual that have always been an important part of the healing process” (Kahn, 2008, p. 1988). Patient etiquette demonstrates respect for the patient and the patient’s values and preferences (patientcentered care).

Patient Education

Patient education is a complex process and should be included in all nursing curricula. If a patient does not have enough information, this can affect care. Some areas that require patient education are identified in the IOM reports, such as tobacco, alcohol, high-fat foods, and firearm injuries. Nurses in community settings typically include such topics in community education, but patients in other settings also need similar counseling. Patient education must be culturally sensitive because the meanings of health, illness, and death are not the same everywhere. For example, some Muslim families believe that this plane of life is just one level of existence, and thus resuscitating the patient is not as important as honoring the predestination of life events. The saving of locks of hair or pictures of Indian babies who are dying is not culturally accepted in all families; some believe that these mementos bind the child to this earthly world and do not allow the child to reach the next.

Keeping the patient in the center of care means that we need to consider what the patient feels is important and listen to the patient. Patient, family, or community health education should also address safety issues such as prevention of medication errors, and its relationship to self-management of care. Health literacy must be considered when patient education is planned, implemented, and evaluated.

Family or Caregiver Roles: Family-Centered Care

Patient advocacy and patient-centered care are directly related to family-centered care. “Family-centered care is a partnership approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care and is grounded in a belief that each participant in a clinical encounter brings valuable experience to the table” (Seyda, Shelton, & DiVenere, 2008, p. 64). One cannot assume that all patients want their families involved, nor can one take for granted what level of involvement there will be and what information may be shared with the family. Patients must be asked about this before steps are taken to communicate with and include the family. The core principles of family-centered care are dignity and respect, information sharing, participation, and collaboration. As with patient-centered care, the overall goal is better outcomes. Family-centered care is “increasingly linked to improved health outcomes, lower healthcare costs, more effective allocation of resources, reduced medical errors and litigation, greater patient, family, and professional satisfaction, increased patient/family self-efficacy/advocacy, and improved medical/health education” (Seyda, Shelton, & DiVenere, 2008, p. 66).

Family-centered care is most likely thought of as relevant only to children’s health, but it applies to all patients. The family will naturally be involved in the support of a dying patient, such as hospice care; and in caring for older family members, a growing responsibility in the United States. Families can be very important in preventing errors; they have valuable information for healthcare providers and may observe as care is provided—asking questions, noting differences, and so on. This can lead to fewer errors and improved communication that reduces the likelihood of litigation.

The Patient-Centered Medical Home Model: A New View of Primary Care

The American Academy of Pediatrics (2007) describes the medical home as a model of delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective. This same model can be applied to adults. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) also describes the medical home. “Every person should have access to a medical home—a person who serves as a trusted advisor and provider supported by a coordinated team—with whom they have a continuous relationship. The medical home promotes prevention; provides care for most problems and serves as the point of first-contact for that care; coordinates care with other providers and community resources when necessary; integrates care across the health system; and provides care and health education in a culturally competent manner in the context of family and community” (AAMC, 2008).

The medical home model is based on patient-centered care. Individualized care is preventive and manages chronic illness. Same-day appointments and expanded appointment hours are more available; tools like secure e-mail enhance communication; prescriptions are transmitted electronically; and electronic health records (EHRs) are used. You can explore and learn more about this concept at http://www.medicalhomeinfo.org. What would be the nurse’s role, both ANPs and non-ANPs, in this model? Research information about medical homes and consider how this new model might affect nursing roles and responsibilities.

Patient- and Family-Centered Rounds

Patient- and family-centered rounds lead to greater patient-centered care (Siserhen, Blaszak, Woods, & Smith, 2007). This should be an interprofessional approach. If, however, nursing staff do not attend these rounds—which they should—then nursing can change nursing rounds only. Rounds should also include the patient’s family if the patient does not object. Engaging the family is important when the family is a significant part of the patient’s life, but in some cases patients may not want family members to hear the information. Students should participate in these important learning opportunities. Rounds demonstrate the impact of care that includes the family, interprofessional teams, communication, coordination, and collaboration. Reflect on the experience and identify examples from the rounds where these activities were evident. Preparation for rounds—communication methods, general process of rounds, when to ask questions, and so on—is important.

Gerontology

We must recognize that the world’s population is aging and that, to provide quality care, we need to educate nurses to meet the special needs of older adults. The IOM recognized the importance of care for the elderly and the chronically ill in the priority areas of care. As noted in Retooling for an Aging America (IOM, 2008c) (see Part 1), there is a growing need to educate staff so they can effectively care for the older adult. There are greater funding opportunities for research and programs focused on this population.

Core Competency: Work on Interdisciplinary/Interprofessional Teams

Cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable (IOM, 2003b, p. 4).

Interprofessional teams work collaboratively and collegially, not in parallel. No health professional plans any aspect of care in isolation; instead, all team members should work together to plan and implement care.

Teamwork

Salmon states, “I must say, I have grown tired of us saying that we are making major strides in collaboration and partnership with others beyond nursing. I worry that we in nursing have fought so hard for our professional identity and autonomy that we see being separate from others as a condition for future success. I see our separateness as antithetical to our most basic professional values. How can we reconcile our commitment to providing the best possible care when we still grapple with the place that nursing assistants, technicians, and others have in relation to our work” (Salmon, 2007, p. 117).

Just as Salmon noted, working in interprofessional teams is a difficult competency to accomplish when we continue to separate healthcare education by professions. We keep healthcare professions separate in most U.S. universities and other types of educational programs. Students are socialized to their own professions in isolation from other healthcare professions. This all affects the quality of care. When healthcare providers do not know how to communicate with one another; when we have abusive language and conflict; when we do not understand our different roles and responsibilities and thus do not know how to make the most of what each profession can offer; when we work against each other rather than with each other to provide care; and when we speak different languages or terminologies, we undermine quality, safe care and are unable to provide patient-centered care. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) reported that “when newly licensed nurses did not work effectively with a healthcare team or did not know when and how to call a patient’s physician, they were more likely to report being involved in patient errors” (Smith & Crawford, 2003, as cited in NCSBN, 2005, p. 5). We are going to have to be creative about developing effective strategies to achieve the competency of working in teams. You need both knowledge and experience working on teams.

Care Coordination

Clinical integration is defined as “the extent to which patient care services are coordinated across people, functions, activities, and sites over time so as to maximize the value of services delivered to patients” (Shortell, Gillies, & Anderson, 2000, as cited in IOM, 2003f, p. 49). Care coordination is an important aspect of all care. Students at all levels

need to understand care coordination and describe the role of nursing. In clinical, ask students how care coordination could be improved, and have them participate in coordination in acute care and in the community. Several reports indicate that interprofessional care is important and should improve. What are the roles of the nurse and the roles of other team members—both nursing staff and other healthcare professionals? How can care coordination be improved? What is the integrator role that some nurses play? What can nurses do to improve interprofessional care coordination? How does this role link to adherence with treatment plans and quality of care? When you plan care for your assigned patients, include care coordination.

need to understand care coordination and describe the role of nursing. In clinical, ask students how care coordination could be improved, and have them participate in coordination in acute care and in the community. Several reports indicate that interprofessional care is important and should improve. What are the roles of the nurse and the roles of other team members—both nursing staff and other healthcare professionals? How can care coordination be improved? What is the integrator role that some nurses play? What can nurses do to improve interprofessional care coordination? How does this role link to adherence with treatment plans and quality of care? When you plan care for your assigned patients, include care coordination.

Interprofessional Collaborative Teams

Precursors to collaboration are individual clinical competence and mutual trust and respect. Collaboration requires shared understanding of goals and roles, shared decision-making, and conflict management. We need to learn how to have a respectful professional dialogue that considers different perspectives. Students also need to understand that although the history of nursing has fostered permissive, submissive language and actions, these do not constitute effective professional communication (Gordon, 2005).

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is highly regarded today, and the IOM reports (for example, Leadership by Example, 2003d) consider it the best leadership approach. This, however, does not mean that it is easy to implement; it is not. You need to understand leadership and followership and appreciate how you respond both as a leader and as a follower. What makes an effective leader and an effective follower?

Most organizations are in a state of perpetual change. You will soon have to step up, take a stand, and be a leader, and this should begin while you are a student (for example, serving on a student committee, planning student activities, and so on). The National Student Nurses Association (NSNA) offers information on leadership and opportunities for leadership experiences (see http://www.nsna.org).

What is empowerment, and why is it important to nurses? Shared governance is one approach that may develop a productive work climate. When you are in healthcare organizations for practicum, ask questions about leadership and organizational effectiveness within the organization. How does the organization respond to change? How well does the staff trust leadership? Why would this be important to know before taking a new position? Consider why it is important to have a close fit between your personal values and the values and mission of the organization.

Allied Health Team Members

Nursing students need to understand the roles of all possible team members, including allied health members. The IOM addressed the issue of the growing number of allied healthcare providers in a workshop in 2011. One of the key issues was defining

allied healthcare providers. “According to Title 42 of the U.S. Code, an allied health professional is a health professional other than a registered nurse or physician assistant who has a certificate, associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctoral degree, or post-baccalaureate training in a science relating to health care and who shares in the responsibility for the delivery of healthcare services or related services, including:

allied healthcare providers. “According to Title 42 of the U.S. Code, an allied health professional is a health professional other than a registered nurse or physician assistant who has a certificate, associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctoral degree, or post-baccalaureate training in a science relating to health care and who shares in the responsibility for the delivery of healthcare services or related services, including:

services related to the identification, evaluation, and prevention of diseases and disorders;

dietary and nutrition services;

health promotion services;

rehabilitation services; or

health system management services.”

The definition excludes those with a “degree in medicine, osteopathy, dentistry, veterinary medicine, optometry, podiatric medicine, pharmacy, public health, chiropractic, health administration, clinical psychology, social work, or counseling” (IOM, 2011a, p. 2). Search for information about allied health roles and responsibilities and then discuss how the team works together with different types of providers. When you first go into healthcare settings, identify different team members and observe what they do with patients and their responsibilities as members of the healthcare team.

Communication

Communication is a complex process that is integrated into everything done in healthcare delivery. Four aspects that typically cause problems are team communication, written communication, issues of verbal abuse among staff, and patient-clinician communication.

Team Communication

Team communication is a critical element in meeting patient needs, providing quality care, and reaching effective patient outcomes. It is intertwined with healthcare professional roles, ability to work with others, recognition that the team is the best method for reaching required goals, and willingness to compromise, collaborate, and coordinate together. It also has a major impact on errors.

Written Communication

The team should be an important element of any discussion about communication, but teams do not just communicate orally. It is easy for students to view documentation as something done to communicate nurse to nurse; however, there is much more to written communication. It helps the entire healthcare team to communicate the plan of care, what has been done, and outcomes. Not only is documentation important to all the healthcare providers, but it also provides data for quality improvement and is essential to reimbursement. Documentation and written communication have important legal

implications, particularly when there are care problems. A source for further discussion and examples of current documentation issues can be found at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/754374?src=ptalk

implications, particularly when there are care problems. A source for further discussion and examples of current documentation issues can be found at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/754374?src=ptalk

Verbal Abuse

Communication skills are always important and should be developed throughout the curriculum. A growing concern for nurses is verbal abuse from other staff, physicians, and family members. In fact, verbal abuse is cited as one of the reasons that nursing is such a stressful profession. Students need guidance in how to respond and examples of the strategies that some HCOs are using to prevent verbal abuse. What is your school’s policy about tolerance of verbal abuse from students, faculty, administrators, or staff?

Patient-Clinician Communication

In 2011, the IOM published a brief report on patient-clinician communication, noting its importance to healthcare delivery, particularly quality care (Paget et al., 2011). Seven basic principles should be integrated into this communication.

Mutual respect

Harmonized goals

A supportive environment

Appropriate decision partners

The right information

Transparency and full disclosure

Continuous learning.

The IOM report discusses each of these principles, all of which are important to nurses.