Incontinence Management, Urinary

In elderly patients, urinary incontinence commonly follows any loss or impairment of urinary sphincter control. The incontinence may be transient or permanent. In all, about 10 million adults experience some form of urinary incontinence; this includes about 50% of the 1.5 million people in extended-care facilities.

Contrary to popular opinion, urinary incontinence is neither a disease nor a part of normal aging. It isn’t inevitable and can be avoided or reversed with support and interventions. Incontinence may be caused by childbirth, confusion, dehydration, fecal impaction, or restricted mobility. It’s also a sign of various disorders, such as prostatic hyperplasia, bladder calculus, bladder cancer, urinary tract infection (UTI), stroke, diabetic neuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, prostatic cancer, prostatitis, spinal cord injury, and urethral stricture. It may also result from urethral sphincter damage after prostatectomy. In addition, certain drugs, including diuretics, hypnotics, sedatives, anticholinergics, antihypertensives, and alpha antagonists, may trigger urinary incontinence.

Urinary incontinence is classified as acute or chronic. Acute urinary incontinence results from disorders that are potentially reversible, such as delirium, dehydration, urine retention, restricted mobility, fecal impaction, infection or inflammation, drug reactions, and polyuria. Chronic urinary incontinence occurs as four distinct types: stress, overflow, urge, and functional (total) incontinence.

With stress incontinence, leakage results from a sudden physical strain, such as a sneeze, cough, or quick movement. With overflow incontinence, urine retention causes dribbling because the distended bladder can’t contract strongly enough to force a urine stream. With urge incontinence, the patient can’t control the impulse to urinate. Finally, with functional incontinence, urine leakage occurs despite the fact that the bladder and urethra are functioning normally and is usually related to cognitive or mobility factors.

Patients with urinary incontinence should be carefully assessed for underlying disorders. Most can be treated; some can even be cured. Treatment aims to control the condition through bladder retraining or other behavioral management techniques, diet modification, drug therapy, pessaries and, possibly, surgery.

Corrective surgery for urinary incontinence includes transurethral resection of the prostate in men, urethral collagen injections for men or women, repair of the anterior vaginal wall or retropelvic suspension of the bladder in women, urethral sling, and bladder augmentation. (See Artificial urinary sphincter implant.)

Corrective surgery for urinary incontinence includes transurethral resection of the prostate in men, urethral collagen injections for men or women, repair of the anterior vaginal wall or retropelvic suspension of the bladder in women, urethral sling, and bladder augmentation. (See Artificial urinary sphincter implant.)

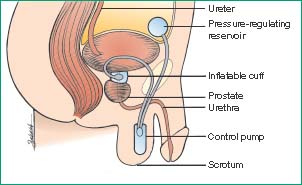

Artificial Urinary Sphincter Implant

An artificial urinary sphincter implant can help restore continence to a patient with a neurogenic bladder. Criteria for inserting an implant include:

incontinence associated with a weak urinary sphincter

incoordination between the detrusor muscle and the urinary sphincter (if drug therapy fails)

inadequate bladder storage (if intermittent catheterization and drug therapy are unsuccessful).

Configuration and Placement

An implant consists of a control pump, an inflatable cuff, and a pressure-regulating reservoir. The cuff is placed around the bladder neck, and the reservoir is placed under the rectus muscle in the abdomen. The reservoir holds fluid that inflates the cuff. In men, the surgeon places the control pump in the scrotum; in women, the surgeon places the pump in the labium.

|

Using the Implant

To void, the patient squeezes the bulb to deflate the cuff, which opens the urethra by returning fluid to the balloon. After voiding, the cuff reinflates automatically, sealing the urethra until the patient needs to void again.

Complications and Care

If complications develop, the implant may need to be repaired or removed. Possible complications include cuff leakage (uncommon), trapped blood or other fluid contaminants (which can cause control pump problems), skin erosion around the bulb or erosion in the bladder neck or the urethra, infection, inadequate occlusion pressures, and kinked tubing. If the bladder holds residual urine, intermittent self-catheterization may be needed.

Care includes avoiding strenuous activity for about 6 months after surgery and having regular checkups.

Equipment

Bladder retraining record sheet ▪ gloves ▪ moisture barrier cream ▪ incontinence pads ▪ bedpan ▪ specimen container ▪ label ▪ laboratory request form ▪ Optional: urinary catheter.

Implementation

Confirm the patient’s identity using at least two patient identifiers according to your facility’s policy.4

Ask when the patient first noticed urine leakage and whether it began suddenly or gradually. Have him describe his typical urinary pattern: Does he usually experience incontinence during the day or at night? Does he get the urge to go again immediately after emptying the bladder? Does he get strong urges to go? Ask him to rate his urinary control: Does he have moderate control, or is he completely incontinent? If he sometimes urinates with control, ask him to identify when and how much he usually urinates.

Evaluate related problems, such as urinary hesitancy, frequency, urgency, nocturia, and decreased force or interruption of the urine stream. Ask the patient to describe any previous treatment received for incontinence or measures the patient has performed. Ask about medications, including nonprescription drugs.5

Assess the patient’s environment. Is a toilet or commode readily available, and how long does the patient take to reach it? After the patient is in the bathroom, assess his manual dexterity; for example, how easily does he manipulate his clothes?

Evaluate the patient’s mental status and cognitive function.

Quantify the patient’s normal daily fluid intake.

Review the patient’s medication and diet history for drugs and foods that affect digestion and elimination.

Review or obtain the patient’s medical history, noting especially any incidence of UTI, diabetes, spinal injury or tumor, stroke, and bladder or pelvic surgery. For a female patient, also note the number and route of births and whether she’s had a hysterectomy; for a male, note any prostate surgery. Assess for such disorders as delirium, dehydration, urine retention, restricted mobility, fecal impaction, infection, inflammation, and polyuria.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access