Immune Response

Immune system functions include protecting the body against invasion by foreign substances, such as microorganisms like bacteria; maintaining homeostasis by removing damaged cells; and destroying tumor cells. Inflammation is not synonymous with infection, although the two terms are often erroneously used interchangeably. Colonization (i.e., the presence of microorganisms without cellular injury) alone does not produce inflammation—cell injury initiates the inflammatory process.

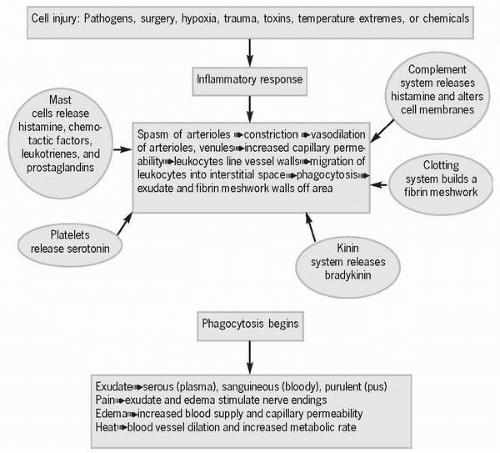

Any cellular injury produces a nonspecific inflammatory response that is generally local but can also be systemic. Infection is only one activity that causes cell injury and inflammation. Other ways a cell can be injured include surgery, hypoxia, trauma, exposure to toxins, or temperature extremes. Regardless of the mechanism of injury, the result is the same: inflammation. When the immune system is overactive, damage to the body from the inflammatory response can occur, such as in autoimmune diseases and hypersensitivity reactions or allergies. By contrast, a weak immune system leads to opportunistic infections and possibly sepsis and malignant disease.

Figure 5-1 Inflammatory response. |

The inflammatory response, indicated by the suffix “-itis,” begins immediately after cell injury when arterioles in the region briefly go into

spasm and constrict to limit bleeding and the extent of the injury. This vasoconstriction is immediately followed by arteriolar and venular vasodilation, which bring increased blood flow to the injured area in an attempt to dilute toxins and provide the area with neutrophils, monocytes, nutrients, and oxygen. As capillary permeability increases, leukocytes line the vessel walls in preparation for emigration into the surrounding tissue. At the same time leukocytes are lining the vessel walls, endothelial cells lining the capillaries and venules react to biochemical mediators that cause these tiny vessels to retract. This retraction makes space for the leukocytes to emigrate, a process by which leukocytes migrate into the interstitial space to begin the process of phagocytosis, or the engulfing and digesting of bacteria in order to clean up cellular debris. Also during this time, fibrinogen transforms into fibrin, which is used to wall off the injured area so that bacteria/toxins are contained, a meshwork for new cells to use in the healing process is formed, and blood clotting begins if blood vessels have been damaged.

spasm and constrict to limit bleeding and the extent of the injury. This vasoconstriction is immediately followed by arteriolar and venular vasodilation, which bring increased blood flow to the injured area in an attempt to dilute toxins and provide the area with neutrophils, monocytes, nutrients, and oxygen. As capillary permeability increases, leukocytes line the vessel walls in preparation for emigration into the surrounding tissue. At the same time leukocytes are lining the vessel walls, endothelial cells lining the capillaries and venules react to biochemical mediators that cause these tiny vessels to retract. This retraction makes space for the leukocytes to emigrate, a process by which leukocytes migrate into the interstitial space to begin the process of phagocytosis, or the engulfing and digesting of bacteria in order to clean up cellular debris. Also during this time, fibrinogen transforms into fibrin, which is used to wall off the injured area so that bacteria/toxins are contained, a meshwork for new cells to use in the healing process is formed, and blood clotting begins if blood vessels have been damaged.

Any cellular injury produces a nonspecific inflammatory response that is generally local but can also be systemic.

Any cellular injury produces a nonspecific inflammatory response that is generally local but can also be systemic.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access