IJK

ILLEGAL ALTERATION OF A MEDICAL RECORD

As a general rule, the medical record is presumed to be accurate if there’s no evidence of fraud or tampering. Tampering or illegal alteration of a medical record includes adding to someone else’s note, destroying the patient’s chart, not recording important details, recording false information, writing an incorrect date or time, adding to previous notes without marking the entry as being late, and rewriting notes. Evidence of tampering can cause the medical record to be ruled inadmissible as evidence in court.

Legal casebook REWRITING RECORDS

In Thor v. Boska (1974), a rewritten copy of a patient’s record was suspected of being an altered record. This lawsuit involved a woman who had seen her doctor several times because of a breast lump. Each time, the doctor examined her and made a record of her visit. After 2 years, the woman sought a second opinion and learned that she had breast cancer. She sued her first doctor. Rather than producing his records in court, the doctor brought copies of the records and said he had copied the originals for legibility. The court reasoned that he was withholding evidence and held in favor of the plaintiff.

In a suspected case of notes written after litigation, the plaintiff’s attorney retains handwriting experts to determine when portions were written.An alteration in the record can make a defensible case indefensible.

Electronic medical records track the date and time of data entry and the identity of the user that’s logged in. To prevent use by another party that would be recorded under your log-in identifiers, be sure to keep your username and password private and log out of the computer whenever you leave it unattended.

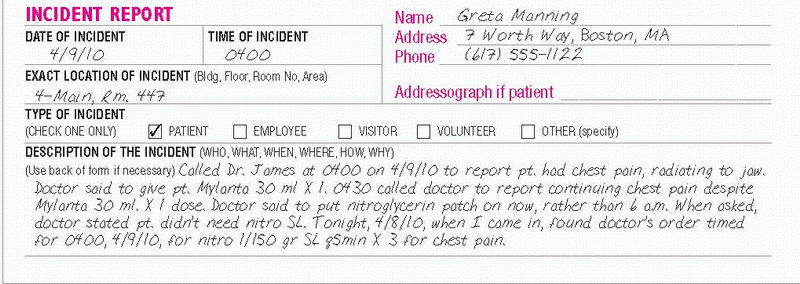

If you suspect that another health care professional has made changes to a medical record, notify your nursing supervisor or risk manager immediately. Avoid the urge to correct the medical record. Moreover, don’t change your notes if requested to do so by another colleague. Complete an incident report, according to your facility’s policy, documenting the alterations that you noted in the medical record or the request by a colleague to change your notes. (See Rewriting records, page 197.)

Essential documentation

Record the date and time that you complete the incident report. Write a factual account of what you observed in the medical record or your conversations with the colleague asking you to alter the record. Include the names and titles of persons you notified.

See Documenting an altered medical record on the incident report for how to report an altered medical record.

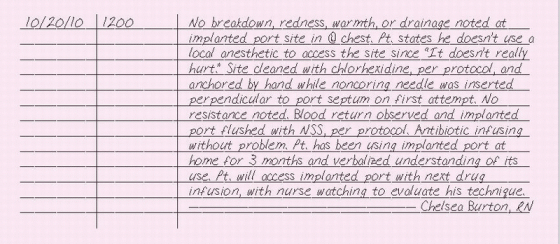

IMPLANTED PORT, ACCESSING

Surgically implanted under local anesthesia by a doctor, an implanted port consists of a silicone catheter attached to a reservoir, which is covered with a self-sealing silicone rubber septum. It’s used most commonly when an external central venous access device isn’t desirable for longterm I.V. therapy. Typically, implanted ports deliver intermittent infusions. They’re used to deliver chemotherapy and other drugs, I.V. fluids, and blood. They can also be used to obtain blood.

To access an implanted port, a noncoring or Huber needle is attached to an extension set, flushed with normal saline solution, and inserted into the reservoir. After checking for blood return, the implanted port is flushed with normal saline solution, according to your facility’s policy.

While the patient is hospitalized, a luer-lock injection cap may be attached to the end of an extension set to provide ready access for intermittent infusions. In addition to saving time, a luer-lock cap reduces the discomfort of accessing the implanted port and prolongs the life of the implanted port septum by decreasing the number of needle punctures.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time that the implanted port was accessed. Note whether signs or symptoms of infection or skin breakdown are present. Describe any pain or discomfort that the patient experienced when the implanted port was accessed. If you used ice or local anesthetic, make sure to chart it. Describe how the area was cleaned before accessing the implanted port. Note whether resistance was met when inserting the needle and whether you obtained a blood return. Include the number of attempts made to access the implanted port. Record any problems with the normal saline flush, such as swelling or pain. Chart the time that the doctor was notified of any problems, his name, any orders given, your interventions, and the patient’s response. Also, document patient education performed.

|

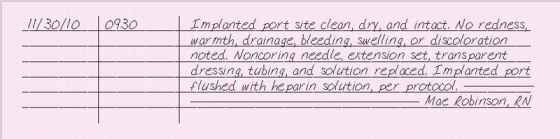

IMPLANTED PORT, CARE OF

After insertion of an implanted port, monitor the site for signs of hematoma and bleeding. Edema and tenderness may persist for about 72 hours. The incision site requires routine postoperative care for 7 to 10 days. You’ll also need to assess the implantation site for signs of infection, port rotation, and skin erosion. No dressing is necessary except during infusions or to maintain an intermittent infusion port.

If your patient is receiving a continuous or prolonged infusion, change a transparent dressing and needle every 7 days. You’ll also need to change the tubing and solution as you would for a long-term central venous infusion.

After a bolus injection or at the end of an infusion, flush the implanted port with normal saline solution followed by heparin, according to your facility’s policy. If your patient is receiving an intermittent infusion, flush the implanted port periodically with heparin solution. When the implanted port isn’t being used, flush it every 4 weeks. During the course of therapy, you may need to clear a clotted implanted port with a fibrinolytic drug, as ordered.

Essential documentation

Record the date and time of your entry. Record the appearance of the site, indicating any bleeding, edema, or hematoma. Document any sign of skin infection or device rotation. Indicate the type of therapy that the patient is receiving, such as continuous infusion or intermittent therapy. Document normal saline solution and heparin flushes as well as measures taken to maintain a patent infusion. Record all dressing, needle, and tubing changes.

|

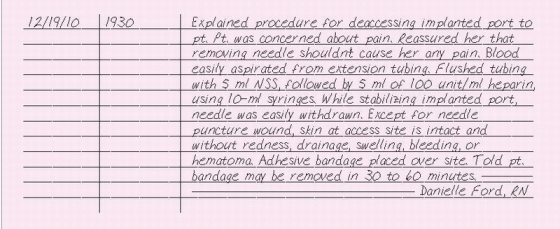

IMPLANTED PORT, WITHDRAWING ACCESS

When you care for a patient with an implanted port, you’ll need to remove the noncoring Huber needle every 7 days (according to your facility’s policy) or at the end of therapy. After you remove the dressing, attach a 10-ml syringe containing normal saline solution, according to facility policy, and aspirate for blood; then flush the catheter. Follow this with a heparin flush in a 10-ml syringe, according to facility policy. As you inject the last 0.5 ml, reclamp the extension tubing to maintain positive forward flow. Stabilize the implanted port with your nondominant thumb and forefinger while you gently pull the needle upward. Protective devices are available to prevent a rebound needle stick. Discard the needle in the appropriate container. Apply an adhesive dressing over the site for 30 to 60 minutes.

Essential documentation

Record the date and time that access is withdrawn from the implanted port, and note that you’ve explained the procedure to the patient. Document the solutions, amounts, and size of the syringes used to flush the extension tubing. Depending on your facility’s policy, these solutions may need to be documented on the medication administration record as well. Note whether you aspirated blood or met resistance. Record that the needle was removed, noting any clots on the needle tip. Describe the condition of the site and the type of dressing applied.

|

INAPPROPRIATE COMMENT IN THE MEDICAL RECORD

Negative language and inappropriate information don’t belong in a medical record. Such comments are unprofessional and can also trigger difficulties in legal cases. A lawyer may use negative or inappropriate comments to show that a patient received poor care. (See Unprofessional documentation.)

Essential documentation

Your documentation in the medical record should contain descriptive, objective information: what you see, hear, feel, smell, measure, and count— not what you suppose, infer, conclude, or assume. Describe events or

behaviors objectively and avoid labeling them with such expressions as “bizarre,” “spaced out,” or “obnoxious.” (See Charting objectively, page 204.)

behaviors objectively and avoid labeling them with such expressions as “bizarre,” “spaced out,” or “obnoxious.” (See Charting objectively, page 204.)

UNPROFESSIONAL DOCUMENTATION

UNPROFESSIONAL DOCUMENTATIONNegative language and inappropriate information don’t belong in a medical record and can be used against you in a lawsuit. For example, one elderly patient’s family became upset after the patient developed pressure ulcers.They complained that the patient wasn’t receiving adequate care. The patient later died of natural causes.

However, because the patient’s family was dissatisfied with the care that the patient received, they sued. In the patient’s chart, under prognosis, the doctor had written “PBBB.” After learning that this stood for “pine box by bedside,” the insurance company was only too happy to settle for a significant sum.

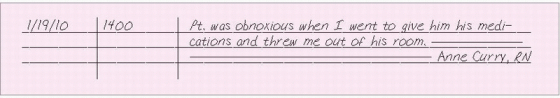

The following note is an example of a nurse using inappropriate words with negative connotations:

|

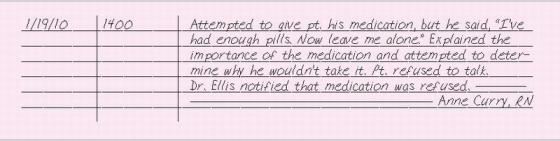

The next note concerns the same situation, but is written objectively:

|

CHARTING OBJECTIVELY

What you say and how you say it are of utmost importance in documentation. Keeping the patient chart free from negative, inappropriate information—potential legal bombshells—can be quite a challenge when you’re writing detailed narrative notes. Here are some guidelines to help you sidestep charting pitfalls and record an accurate account of your patient’s care and status.

AVOID REPORTING STAFFING PROBLEMS

Even though staff shortages may affect patient care or contribute to an incident, you shouldn’t refer to staffing problems in a patient’s chart. Instead, discuss them in a forum that can help resolve the problem. In a confidential memo or an incident report, call the situation to the at tention of the appropriate personnel such as your nurse-manager. Also review your hospital’s policy and procedure manuals to determine how you’re expected to handle this situation.

KEEP STAFF CONFLICTS AND RIVALRIES OUT OF THE RECORD

Entries about disputes with nursing colleagues (including characterization and criticism of care provided), questions about a doctor’s treatment decisions, or reports of a colleague’s rude or abusive behavior reflect personality clashes and don’t belong in the medical record. They aren’t legitimate concerns about patient care.

As with staffing problems, address concerns about a colleague’s judgment or competence in the appropriate setting. After making sure that you have the facts, talk with your nurse-manager. Consult with the doctor directly if an order concerns you. Share your opinions, observations, or reservations about colleagues with your nurse-manager only; avoid mention ing them in a patient’s chart.

If you discover personal accusations or charges of incompetence in a chart, discuss this with your supervisor.

STEER CLEAR OF WORDS ASSOCIATED WITH ERRORS

Terms such as by mistake, accidentally, some how, unintentionally, miscalculated, and confusing can be interpreted as admissions of wrongdoing. Instead, let the facts speak for themselves—for example,“Pt. was given De merol 100 mg I.M. at 1300 hours for abdominal pain. Doctor Jones was notified at 1305 and is on his way here. Pt.’s vital signs are BP 120/82, P 80, RR 20,T 98.4° F.”

If the ordered drug dose was 50 mg, this entry will let other health care providers know that the patient was overmedicated.

AVOID BIAS

Don’t use words that suggest a negative attitude toward the patient. For example, don’t use unflattering or unprofessional adjectives, such as obstinate, drunk, obnoxious, bizarre, or abusive, to describe the patient’s behavior. If a patient is difficult or uncooperative, document the behavior objectively. Negative words could cause a plaintiff’s attorney to attack your professionalism with an argument such as this: “Look at how this nurse felt about my client— she called him ‘rude, difficult, and uncooperative.’ No wonder she didn’t take good care of him; she didn’t like him.”

DON’T ASSUME

Always aim to record the facts about a situa tion, not your assumptions or conclusions. Record only what you see and hear. For exam ple, don’t record that a patient pulled out an I.V. line if you didn’t witness him doing so. Do, however, describe your findings—for example, “Found pt, arm board, and bed linens covered with blood. I.V. line and I.V. catheter were untaped and hanging free.”

INCIDENT REPORT

An incident is an event that’s inconsistent with the facility’s ordinary routine, regardless of whether injury occurs. In most health care facilities, any injury to a patient requires an incident report (also known as an event report or occurrence report). Patient complaints, medication errors, and injuries to employees and visitors require incident reports as well. (See Reporting an incident.) An incident report serves two main purposes:

to inform hospital administration of the incident so that it can monitor patterns and trends, thereby helping to prevent future similar incidents (risk management).

to alert the administration and the hospital’s insurance company to the possibility of liability claims and the need for further investigation (claims management).

Essential documentation

When filing an incident report, include only the following information:

the exact time and place of the incident.

the names of the persons involved and any witnesses.

factual information about what happened and the consequences to the person involved (supply enough information so administration can decide whether the matter needs further investigation).

any relevant facts (such as your immediate actions in response to the incident; for example, notifying the patient’s doctor).

REPORTING AN INCIDENT

REPORTING AN INCIDENTAs a nurse, you have a duty to report any incident of which you have first-hand knowledge. Not only can failure to report an incident lead to your being fired, but it can also expose you to personal liability for malpractice—especially if your failure to report the incident causes injury to a patient.

When you do file an incident report, don’t indicate in the patient’s chart that an incident report has been completed. This destroys the confidential nature of the report and may result in a lawsuit.

An incident involving a patient should also be recorded in his medical record. If you don’t document the incident, treatment, follow-up care, and patient’s response, the plaintiff’s attorney might think you’re hiding something. If the case goes to court, the jury may be asked to determine if the patient received appropriate care after the incident.

Include in the incident report and progress note any statements made by the patient or his family concerning their role in the incident. For example,“Patient stated,‘The nurse told me to ask for help before I went to the bathroom, but I decided to go on my own.’” This kind of statement helps the defense attorney prove that the patient was entirely or partially at fault. If the jury finds that the patient was partially at fault, the concept of contributory negligence may be used to reduce or even eliminate the patient’s recovery of damages.

TIPS FOR WRITING AN INCIDENT REPORT

When a malpractice lawsuit reached the courtroom in years past, the plaintiff’s attorney wasn’t allowed to see incident reports.Today, in many states, the plaintiff is legally entitled to a record of the incident if he requests it through the proper channels.

When writing an incident report, keep in mind the people who may read it and follow these guidelines.

WRITE OBJECTIVELY

Record the details of the incident in objective terms, describing exactly what you saw and heard. For example, unless you actually saw a patient fall, write:“Found patient lying on the floor.” Then describe only the actions you took to provide care at the scene, such as helping the patient back into bed, assessing him for injuries, and calling the doctor.

AVOID OPINIONS

Don’t commit your opinions to writing in the incident report. Rather, verbally share your sug gestions or opinions on how an incident may be avoided with your supervisor and risk manager.

ASSIGN NO BLAME

Don’t admit to liability and don’t blame or point your finger at colleagues or administrators. Steer clear of such statements as “Better staffing would have prevented this incident.” State only what happened.

AVOID HEARSAY AND ASSUMPTIONS

Each staff member who knows about the incident dent should write a separate incident report. If one of your patients is injured in another department, the staff members in that department are responsible for documenting the details of the incident.

FILE THE REPORT PROPERLY

Don’t file the incident report with the medical record. Send the report to the person designated to review it according to your facility’s policy.

After completing the incident report, sign and date it. (See Tips for writing an incident report.)

An incident must also be documented in the patient’s medical record. Write a factual account of the incident, including the treatment, follow-up care, and the patient’s response. Include in the progress note and in the incident report anything the patient or his family says about their role in the incident.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

DOCUMENTING AN ALTERED MEDICAL RECORD ON THE INCIDENT REPORT

DOCUMENTING AN ALTERED MEDICAL RECORD ON THE INCIDENT REPORT