Hypoglycemia

Potentially dangerous, hypoglycemia is an abnormally low blood glucose level. It occurs when glucose metabolizes too rapidly, when the glucose release rate falls behind tissue demands, or when excessive insulin enters the bloodstream. When the brain is deprived of glucose, as with oxygen deprivation, its functioning becomes deranged. With prolonged glucose deprivation, tissue damage—or even death—may occur.

Hypoglycemia may be classified as reactive, pharmacologic, or fasting. Reactive hypoglycemia results from the reaction to the disposition of meals. Blood glucose levels typically fall 2 to 4 hours after a meal.

Pharmacologic hypoglycemia results in response to a drug that does one of the following: increases the amount of insulin circulating in the blood, enhances insulin action, or impairs the liver’s glucose–producing capacity. Blood glucose levels may fall slowly or rapidly.

Fasting hypoglycemia causes discomfort during periods of abstinence from food. Blood glucose levels fall gradually. Signs and symptoms don’t occur until 5 hours or more after a meal. This rare type of hypoglycemia occurs most commonly during the night.

Manifestations of hypoglycemia tend to be vague and depend on how quickly the patient’s glucose levels drop. Gradual onset of hypoglycemia produces predominantly central nervous system (CNS) signs and symptoms; a more rapid decline in plasma glucose levels results predominantly in adrenergic signs and symptoms. (See Acute hypoglycemia, pages 448 and 449.)

Causes

Reactive hypoglycemia may take several forms. In a diabetic patient, it may result from the administration of too much insulin or, less commonly, too much oral antidiabetic medication. In a patient with mild diabetes (or in the early stages of diabetes mellitus), reactive hypoglycemia may result from delayed and excessive insulin production after carbohydrate ingestion. Increased physical activity without a change in insulin dosages can also lead to hypoglycemia. Similarly, a nondiabetic patient may suffer reactive hypoglycemia from a sharp increase in insulin output after a meal. Sometimes called postprandial hypoglycemia, this type of reactive hypoglycemia usually disappears when the patient eats something sweet. In some patients, reactive hypoglycemia may have no known cause (idiopathic reactive) or may result from total parenteral nutrition for gastric dumping syndrome or from impaired glucose tolerance.

Fasting hypoglycemia usually results from an excess of insulin or insulin–like substance or from a decrease in counter regulatory hormones. It can be exogenous, resulting from external factors, such as alcohol or drug ingestion, or endogenous, resulting from inorganic problems. Endogenous hypoglycemia may result from tumors or liver disease. Insulinomas, small islet cell tumors in the pancreas, secrete excessive amounts of insulin, which inhibits hepatic glucose production. These tumors are usually benign (in 90% of patients). Extrapancreatic tumors, although uncommon, can also cause hypoglycemia by increasing glucose utilization and inhibiting glucose output. Such tumors occur primarily in the mesenchyma, liver, adrenal cortex, GI system, and lymphatic system. They may be benign or malignant.

Among nonendocrine causes of fasting hypoglycemia are severe hepatic diseases, including hepatitis, cancer, cirrhosis, and liver congestion associated with heart failure. All of these conditions reduce the uptake and release of glycogen from the liver.

Endocrine causes include destruction of pancreatic islet cells; adrenocortical insufficiency,

which contributes to hypoglycemia by reducing the production of cortisol and cortisone needed for gluconeogenesis; and pituitary insufficiency, which reduces corticotropin and growth hormone levels.

which contributes to hypoglycemia by reducing the production of cortisol and cortisone needed for gluconeogenesis; and pituitary insufficiency, which reduces corticotropin and growth hormone levels.

Life-threatening complications

Life-threatening complicationsAcute hypoglycemia

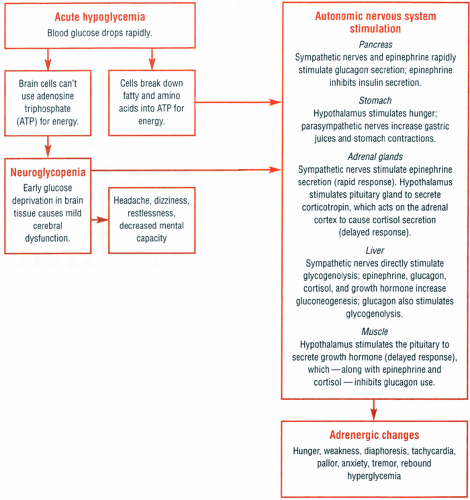

Normally, homeostatic mechanisms maintain blood glucose levels within narrow limits (60 to 120 mg/dl). The body burns available glucose and stores the rest as glycogen in the liver and muscles. When the glucose level drops, the liver converts glycogen back to glucose (glycogenolysis) or makes new glucose from noncarbohydrate sources, such as amino acids or fatty acids (gluconeogenesis).

Hormones maintain the delicate balance between glucose production and use. However, this balance is upset when a patient has hypoglycemia. The flowchart at right shows the events that lead to CNS and autonomic nervous system reactions associated with hypoglycemia.

Signs and symptoms

Acute hypoglycemia initially causes signs and symptoms of mild cerebral dysfunction, such as headache, dizziness, restlessness, and decreased mental capacity. If left untreated, the blood glucose level continues to drop, producing such adrenergic signs and symptoms as hunger, weakness, diaphoresis, tachycardia, pallor, anxiety, tremor, and possibly rebound hyperglycemia. If hypoglycemia continues, any beneficial effects of rebound hyperglycemia quickly dissipate and coma, seizures, and permanent brain damage or even death may follow.

Emergency interventions

The patient’s signs and symptoms determine which interventions to take.

For severe hypoglycemia (suggested by confusion or coma), expect to administer 25 to 50 g of 50% glucose solution by I.V. bolus, followed by continuous glucose infusion until the patient can eat a meal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access