A look at high-risk pregnancy

Pregnancy is a relatively normal process; however, for those women that may have a preexisting condition, pregnancy can have many implications. In addition, a complication can occur at any time during pregnancy, regardless of the mother’s efforts of self-care. Complications may occur with fertilization, or at any time throughout the pregnancy, even up to the time of delivery. Complications may also occur with an external factor that can impact the health and well-being of the mother or the fetus.

Mother + fetus = one

Keep in mind that the health of a woman and her fetus are interdependent. Changes in the woman’s health may affect fetal health, and changes in fetal health may affect the mother’s physical and emotional health.

Group effort

A high-risk pregnancy can be multifactorial. Many factors can work together to contribute to a high-risk situation. For example, a pregnant adolescent is considered at higher risk; however, it isn’t simply her age that places her in this category. Rather, her age is an indication of other factors that contribute to increased risk. First, as a pregnant adolescent, she faces a developmental crisis. In addition, adolescents in general tend to lack proper nutrition, adequate support, and knowledge—all these factors alone may contribute to an increased risk during pregnancy. Conditions such as iron deficiency anemia, gestational hypertension, and preterm labor can occur more frequently in adolescents as opposed to older women.

Maternal age

Reproductive risks increase among adolescents younger than age 15 and women older than age 35. The adolescent patient faces serious risks, including increased incidence of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) and preterm labor, anemia, labor dysfunction, cephalopelvic disproportion, cesarean birth, preeclampsia, and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Expectant mothers older than age 35 are at risk for obstetrical complications such as placenta previa; hydatidiform mole; and vascular, neoplastic, degenerative diseases; increased risk of fetal death; and perinatal morbidity and mortality. They’re also at risk for having fraternal twins or infants with genetic abnormalities, especially Down syndrome.

Maternal parity

Maternal parity may place a pregnant woman at high risk. For example, a multigravida who has had five or more pregnancies lasting at least 20 weeks is considered high risk. In addition, if the current pregnancy occurs within 3 months of the last delivery, the pregnancy is considered high risk.

Maternal obstetric and gynecologic history

Many factors in the mother’s obstetric and gynecologic history can place a pregnancy at high risk. These factors may include:

grand multiparity

previous preterm labor or preterm birth, previous low-birthweight infant

one or more stillbirths at term

one or more neonates born with gross anomalies, neurologic deficit, or birth injury

pelvic inadequacy or abnormal shaping

last delivery less than 1 year before conception

uterine or cervical incompetency, position, or structural anomalies

history of infertility

history of multiple pregnancy, placental anomalies, amniotic fluid abnormalities, or poor weight gain

history of gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, or infection

history of delivering a postterm or macrosomic infant

history of dystocia or prolonged labor precipitous delivery, cervical or vaginal lacerations caused by labor and delivery, previ ous midforceps delivery, cephalopelvic disproportion, hemorrhage during labor and delivery, retained placenta, or previous cesarean birth

lack of previous prenatal care.

In addition, a pregnancy that occurs within 3 years of menarche indicates an increased risk of maternal mortality and morbidity. Such a pregnancy also places the patient at risk for delivering a neonate who’s small for gestational age.

Maternal medical history

A careful assessment of the mothers’ medical, gynecologic and obstetric history is necessary in order to determine any risk factors associated with the current pregnancy. A medical history of cardiac or metabolic disease, seizure disorders, cancer, emotional disorders, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), endocrine disorders, pulmonary disease, or any type of surgery during the current pregnancy may pose a threat to maternal or fetal well-being.

Insulin influx

Diabetes can worsen during pregnancy and harm the mother and fetus. Because pregnant women typically develop insulin resistance, women with diabetes need increased amounts of insulin during pregnancy. The fetus of a woman with diabetes tends to be large because the increased insulin production needed to counteract the overload of glucose from the mother stimulates fetal growth. This, in turn, can lead to problems of cephalopelvic disproportion and dystocia for the mother and puts her at risk for postpartum hemorrhage. The newborn is also at risk for traumatic injuries, such as a shoulder dystocia, which can lead to brachial plexus injury or a broken clavicle.

Gravida aggravations

Stomach displacement by the gravid uterus, along with cardiac sphincter relaxation and decreased gastrointestinal (GI) motility caused by increased progesterone, may aggravate symptoms of peptic ulcer disease such as gastric reflux. Also, the increase in blood volume and cardiac output associated with pregnancy can exhaust a patient with underlying cardiac disease.

Maternal lifestyle

Psychosocial and lifestyle factors also need to be considered: poor nutrition, insufficient finances, smoking, substance abuse, heavy lifting, long periods of standing, or stress can also have a negative effect on the current pregnancy. Make the patient aware that what she consumes and what she’s exposed to can seriously affect her pregnancy. For example, taking over-the-counter and prescription drugs can be detrimental to the fetus. In addition, cigarette smoking is associated with IUGR and low-birth-weight neonates. Exposure to toxic substances, such as lead, organic solvents, radiation, and carbon monoxide, can also lead to fetal malformations.

Substance sabotage

Substance use or abuse of drugs or alcohol is another cause of fetal anomalies. After birth, the neonate may experience withdrawal. Substance abuse may also interfere with the pregnant woman’s ability to obtain adequate nutrition, which can adversely affect fetal growth. Additionally, if the ˆ substance abuse involves injection, the pregnant woman is at risk for infection with hepatitis B and HIV.

Nourish to flourish

Adequate nutrition is especially vital during pregnancy. Inadequate nutrition can lead to a deficiency of iron, folic acid, or protein. Iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy is associated with low fetal birth weight and preterm birth. Folic acid deficiency is associated with neural tube defects. Protein deficiency can lead to poor development of the fetus and growth restriction.

Cultural background

Several genetic disorders are associated with specific cultures. For example, sickle cell anemia occurs primarily in persons of African and Mediterranean descent. Tay-Sachs disease is about

100 times more common in people of Eastern European Jewish (Ashkenazi) ancestry than in the general population.

Faith and the fetus

A woman’s religious practices may also affect her health during pregnancy and could predispose her to complications. For example, an Amish woman may not be immunized against rubella. If the woman is exposed, her fetus is at risk for congenital anomalies. Seventh-Day Adventists traditionally exclude dairy products from their diets, which may conflict with the woman’s need for additional calcium for fetal bone growth.

Family history

Certain conditions and disorders that contribute to highrisk pregnancy are familial. For example, a family history of multiple births, congenital diseases or deformities, or mental disability may place a pregnancy at higher risk.

Don’t forget Dad

Some fetal congenital anomalies may be traced to the father’s exposure to environmental hazards. The father’s blood type and Rh status are also important because isoimmunization in the fetus may occur if the father is Rh-positive, the mother is Rh-negative, and the fetus is Rh-positive.

On the home front

The family environment is also important in determining whether a pregnancy is high risk. A history of domestic violence, a lack of support persons, inadequate housing, social issues, single parent, uninvolved father of the baby, minority status, psychiatric history, or lack of adequate finances can increase risk during pregnancy.

Abruptio placentae

Abruptio placentae or premature separation of the placenta, occurs when a normally implanted placenta detaches from the uterine wall prematurely, typically seen after 20 weeks’ gestation. Abruptio placentae is the leading cause of perinatal mortality and is considered to be an obstetric emergency as it can result in severe hemorrhage and/or maternal or fetal death.

What causes it

The cause of abruptio placentae is unknown. Predisposing factors include:

traumatic injury such as a direct blow to the uterus (domestic violence or accident)

placental site bleeding caused by a needle puncture during amniocentesis

chronic hypertension or gestational hypertension, which raises pressure on the maternal side of the placenta

multiparity (more than 5)

short umbilical cord

dietary deficiency

smoking

cocaine abuse

preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM)

What to look for

Abruptio placentae produces a wide range of signs and symptoms, such as sudden and forceful severe and steady pain; hard, boardlike abdomen; external or concealed dark red blood; fetal heart tones may be present or absent; and dilation occurs very rapidly. In addition to the major complications of abruptio placentae— hemorrhage and shock—it may also cause renal failure, pituitary necrosis (Sheehan syndrome), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and maternal and fetal death.

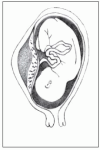

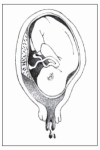

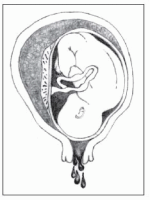

Three degrees of separation

Three degrees of separation can occur with abruptio placentae:

Mild

Mild abruptio placentae (marginal separation) develops gradually and produces mild to moderate bleeding, vague lower abdominal discomfort, mild to moderate abdominal tenderness, and uterine irritability. Fetal heart tones remain strong and regular.

Moderate

Moderate abruptio placentae (about 50% placental separation) may develop gradually or abruptly and produces continuous abdominal pain, moderate dark red vaginal bleeding, a tender uterus that remains firm between contractions, barely audible or irregular and bradycardic fetal heart tones and, possibly, signs of shock. Labor typically starts within 2 hours and usually proceeds rapidly.

Severe

Severe abruptio placentae (70% placental separation) develops abruptly and causes agonizing, unremitting uterine pain (described as tearing or knifelike); a boardlike, tender uterus; moderate vaginal bleeding; rapidly progressive shock; and absence of fetal heart tones (related to fetal cardiac distress). (See

Placental separation in abruptio placentae.)

What tests tell you

Vaginal examination (in preparation for emergency cesarean delivery) and ultrasonography are performed to rule out placenta previa. Decreased hemoglobin levels and platelet counts support the diagnosis. Periodic assays for fibrin split products aid in monitoring the progression of abruptio placentae and in detecting DIC. Differential diagnosis excludes placenta previa, ovarian cysts, appendicitis, and degeneration of leiomyomas. ×

How it’s treated

Treatment of abruptio placentae focuses on assessing, controlling, and restoring the amount of blood lost; delivering a viable neonate; and preventing coagulation disorders.

First things first!

Immediate measures for treatment of abruptio placentae include:

starting an I.V. infusion (through a large-bore catheter) of lactated Ringer solution to combat hypovolemia

placing a central venous pressure (CVP) line and urinary catheter to monitor fluid status

drawing blood for hemoglobin level, hematocrit, coagulation studies, and typing and crossmatching

external electronic fetal monitoring and monitoring of maternal vital signs and vaginal bleeding

administering blood replacement as necessary.

Delivery details

After the severity of abruption has been determined and fluid and blood have been replaced, prompt cesarean delivery is necessary if the fetus is in distress or if heavy bleeding continues. If the fetus isn’t in distress, monitoring continues.

Because of possible fetal blood loss through the placenta, a pediatric team should be ready at delivery to assess and treat the neonate for shock, blood loss, and hypoxia. If placental separation is severe and no signs of fetal life are present, vaginal delivery may be performed unless it’s contraindicated by uncontrolled hemorrhage or other complications.

What to do

Assess the patient’s extent of bleeding and monitor fundal height every 30 minutes for changes. Count the number of perineal pads used by the patient, weighing them as needed to determine the amount of blood loss.

Monitor maternal blood pressure, pulse rate, respirations, CVP, intake and output, and amount of vaginal bleeding every 10 to 15 minutes.

Begin electronic fetal monitoring to assess fetal heart rate (FHR) continuously.

Have equipment for emergency cesarean delivery readily available.

If vaginal delivery is elected, provide emotional support during labor. Because of the neonate’s prematurity, the mother may not receive analgesics during labor and may experience intense pain. Reassure the patient of her progress through labor, and keep her informed of the fetus’s condition.

Prepare the patient and her family for the possibility of an emergency cesarean delivery of a premature neonate and the changes to expect in the postpartum period. Offer emotional support and an honest assessment of the situation.

Tactfully discuss the possibility of neonatal death. Tell the mother that the neonate’s survival depends primarily on gestational age, the amount of blood lost, and associated hypertensive disorders. Assure her that frequent monitoring and prompt management greatly reduce the risk of death.

Encourage the patient and her family to verbalize their feelings.

Help the patient and her family develop effective coping strategies. Refer them for counseling if necessary.

Cardiac disease

The pregnant woman with preexisting cardiac disease is considered high risk. Despite improvements in early identification and management of cardiac problems, these disorders contribute to complications in approximately 1% of pregnancies.

Rating the risk

The type and extent of the woman’s cardiac disease determine whether she can successfully complete a pregnancy. Guidelines developed by the New York Heart Association are commonly used to predict a pregnancy’s outcome. These guidelines categorize pregnancy based on the degree of compromise. (See

Cardiac disease classification,

page 222.)

What causes it

The most common underlying cause of cardiac disease in pregnancy involves congenital anomalies, such as atrial septal defect and coarctation of the aorta that hasn’t been corrected. Valvular disease caused by rheumatic fever or Kawasaki disease may also be an underlying problem. Moreover, with an increase in the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age, the incidences of ischemic cardiac disease and myocardial infarction are increasing.

On rare occasion

Peripartal cardiomyopathy (cardiac disease that manifests primarily with pregnancy) is rare. Although the exact cause is unknown, it’s believed to result from the effects of pregnancy on the circulatory system. In many cases, previously undiagnosed cardiac disease is the cause.

What to look for

Signs and symptoms of cardiac disease in a pregnant woman depend on the type and severity of the underlying disease. Primarily, these signs and symptoms are those associated with heart failure. (See

The weaker weeks,

page 222.) Fetal signs of maternal cardiac disease are nonspecific—such as abnormally low FHR and fetal growth retardation—so diagnosis depends mainly on maternal signs and symptoms.

Failure to the left

Left-sided heart failure occurs with such conditions as mitral valve disorder and congenital coarctation of the aorta. Common signs and symptoms are those associated with pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary edema and may include:

decreased systemic blood pressure

productive cough with blood-streaked sputum

tachypnea

dyspnea on exertion, progressing to dyspnea at rest

tachycardia

orthopnea

paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

edema.

Failure to the right

Right-sided heart failure can occur in a woman with a congenital heart defect, such as atrial and ventricular septal defect and pulmonary valve stenosis. Signs and symptoms may include:

My, oh, myocardial failure

For the woman with peripartal cardiac disease, signs and symptoms typically reflect myocardial failure. Shortness of breath, chest pain, and edema are common. Cardiomegaly also may occur.

What tests tell you

An electrocardiogram (ECG) may show cardiac changes in the mother but may be less accurate later in pregnancy as the enlarged uterus pushes the diaphragm upward and displaces the heart. Echocardiography shows cardiomegaly. If the mother’s cardiac decompensation has reached the point of placental insufficiency and incompetency, late decelerations during fetal monitoring may indicate fetal distress. Ultrasonography may show growth retardation.

How it’s treated

Treatment focuses on ensuring the health and safety of the mother and fetus. Commonly, more frequent prenatal visits are scheduled, such as every 2 weeks and then every week during the last month, to achieve this goal.

Minor adjustments

If the woman was taking cardiac medications before becoming pregnant, the medications are typically continued during pregnancy. However, maintenance doses may need to be increased to aid in compensating for the increased blood volume associated with pregnancy.

Prophylactic tactics

For women with valvular or congenital cardiac disease, some practitioners may begin prophylactic antibiotic therapy near to the patient’s expected due date to prevent the development of possible subacute bacterial endocarditis secondary to bacterial invasion from the placental site into the bloodstream, although the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) are not recommending prophylactic antibiotics routinely if having an uncomplicated vaginal or cesarean delivery. Antibiotics are optional and should be based on specific and individual risk factors and type of delivery. If the woman was taking prophylactic antibiotics to prevent a recurrence of rheumatic fever before becoming pregnant, they’re continued during pregnancy.

Rest for the weary

Another key area of treatment is rest. A pregnant woman with cardiac disease requires more rest than the average pregnant woman. In addition, practitioners commonly recommend

complete bed rest for the woman after gestational week 30 to ensure the fetus is carried to term or at least to week 36.

A weighty subject

Maintaining good nutrition is an important component of ensuring a healthy mother and fetus. For the woman with cardiac disease, it’s especially important that weight gain be balanced to ensure that the nutritional needs of the mother and fetus are met while also ensuring that the mother’s heart isn’t overburdened. As a general practice, salt intake may be limited; however, it shouldn’t be severely restricted because sodium is needed for fluid volume. Prenatal vitamins are essential to help ensure adequate iron intake and avoid anemia, which reduces the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen. The pregnant woman with cardiac disease and her fetus need as much oxygen as possible, so anemia must be avoided.

What to do

Assess maternal vital signs and cardiopulmonary status/closely for changes; question the patient about increased shortness of breath, palpitations, or edema; monitor FHR for changes.

Monitor weight gain throughout pregnancy. Assess for edema and note any pitting.

Explain signs and symptoms of worsening disease and \ tell the patient to report them immediately.

Reinforce use of prescribed medications to control cardiac disease. Explain possible adverse reactions to these medications and instruct the patient to report these reactions immediately.

Anticipate the need for increased doses of maintenance medications; explain to the patient the rationale for this increase.

Assess the woman’s nutritional pattern. Work with her to develop a feasible meal plan. Stress the need for prenatal vitamins.

Assess FHR and ultrasound results to monitor fetal growth.

Encourage frequent rest periods throughout the day. Discuss measures for pacing activities and conserving energy.

Advise the woman to immediately report signs and symptoms of infection, such as upper respiratory or urinary tract infection (UTI), to prevent overtaxing the heart.

Advise the woman to rest in the left lateral recumbent position to prevent supine hypotension and provide the best possible oxygen exchange to the fetus; if necessary, use semi-Fowler position to relieve dyspnea.

Prepare the woman for labor, anticipating the use of epidural anesthesia to avoid overtaxing the patient’s heart.

Monitor FHR, uterine contractions, and maternal vital signs closely for changes during labor.

Assess vital signs closely after delivery. Anticipate anticoagulant and cardiac glycoside therapy immediately after delivery for the woman with severe heart failure.

Encourage ambulation, as ordered, as soon as possible after delivery.

Anticipate administration of prophylactic antibiotics, if not already ordered, after delivery to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia (elevated serum glucose level) resulting from lack of insulin, lack of insulin effect, or both. It’s a disorder of carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism.

Three general classifications are recognized:

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes (absolute insulin insufficiency) usually occurs before age 30, although it may occur at any age. The patient is typically thin and requires exogenous insulin and dietary management to achieve control.

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (insulin resistance with varying degrees of insulin secretory defects) usually occurs in obese adults after age 40. It’s treated with diet and exercise in combination with various antidiabetic drugs, although treatment may also include insulin therapy.

Gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes (diabetes that emerges during pregnancy) typically develops during the middle of the pregnancy when insulin resistance is most apparent.

Losing balance

Diabetes affects at least 7% and may affect up to 18% of all pregnancies in the United States. The overall challenge associated with diabetes and pregnancy is controlling the balance between glucose levels and insulin requirements. Poor glucose control can adversely affect the mother, the fetus, or both. The risk of gestational hypertension and infection (most commonly candidal infections) is higher in pregnant women with diabetes. Moreover, continued fetal consumption of glucose may lead to maternal hypoglycemia, especially between meals and during the night. Additionally, polyhydramnios (increased amount of amniotic fluid) may occur because of increased fetal urine production caused by fetal hyperglycemia.

Neonates who are born to mothers with poorly controlled diabetes typically are large, possibly more than 4.5 kg (10 lb). This large size may complicate labor and delivery, necessitating a cesarean birth. The risks of congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortions, and stillbirths also increase in women with poorly controlled or uncontrolled diabetes.

What causes it

Evidence indicates that diabetes has various causes, including:

heredity

environment (infection, diet, exposure to toxins and stress)

lifestyle in genetically susceptible persons.

Unwanted relative

Although the cause of type 1 diabetes isn’t known, scientists believe that the tendency to develop diabetes may be inherited and related to viruses. In persons with a supposed genetic

predisposition to type 1 diabetes, a triggering event (possibly infection with a virus) spurs the production of autoantibodies that destroy the pancreas’s beta cells. The destruction of beta cells causes insulin secretion to decrease or ultimately stop. When more than 90% of the beta cells have been destroyed, the subsequent insulin deficiency leads to hyperglycemia, enhanced lipolysis (decomposition of fat), and protein catabolism.

Impaired, inappropriate …

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic disease caused by one or more of these factors:

impaired insulin production

inappropriate hepatic glucose production

peripheral insulin receptor insensitivity

history of gestational diabetes

stress.

… and intolerant

Gestational diabetes occurs when a woman who hasn’t been previously diagnosed with diabetes shows glucose intolerance during pregnancy. Of those women who don’t have diabetes when they become pregnant, approximately 3% develop gestational diabetes. It isn’t known whether gestational diabetes results from inadequate insulin response to carbohydrates, excessive insulin resistance, or both. Identifiable risk factors include:

obesity

history of delivering large neonates (usually more than 4.5 kg [10 lb]), unexplained fetal or perinatal loss, or evidence of congenital anomalies in previous pregnancies

age older than 25

family history of diabetes.

What to look for

The signs and symptoms noted in the pregnant woman with diabetes are the same as those for any person with diabetes. Common signs and symptoms include hyperglycemia, glycosuria, and polyuria. Dizziness and confusion may be related to hyperglycemia. In addition, the woman may experience an increased incidence of monilial infections. Hydramnios may be present along with poor FHR and variability arising from inadequate tissue (placental) perfusion.

The woman with type 1 or 2 diabetes may also exhibit signs and symptoms related to microvascular and macrovascular changes, such as peripheral vascular disease, retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.

What tests tell you

All women are screened for gestational diabetes during pregnancy. Testing typically occurs between weeks 24 and 28, when the diabetic hormones are influencing insulin performance, and may be repeated at week 32 if the woman is obese or older than age 40. If the woman has risk factors for gestational diabetes, this screening takes place at the first prenatal visit and again between weeks 24 and 28.

The glucose challenge

Screening involves an oral glucose challenge test (a test that obtains a fasting plasma glucose level) using a 50-g glucose solution (glucola). One hour after ingestion, a venous blood sample is obtained. If the glucose level is greater than 180 mg/dl (some health care centers use a value of 200 mg/dl), the woman

is scheduled for a 3-hour fasting glucose tolerance test using a 100-g glucose load. Plasma glucose results are determined at 1-, 2-, and 3-hour intervals after ingestion of the glucose solution (See

Glucose challenge values in pregnancy.)

If the woman is known to have diabetes, serial blood glucose monitoring and measurement of glycosylated hemoglobin levels are used to determine the degree of glucose control.

How it’s treated

Any woman with diabetes, whether preexisting or gestational, requires more frequent prenatal visits to ensure optimal control of glucose levels, minimizing the risks to the woman and her fetus. Additionally, treatment focuses on balancing rest with exercise and maintaining adequate nutrition for fetal growth and control of blood glucose levels.

Ideally, the woman with preexisting diabetes should consult with her practitioner before becoming pregnant to ensure the best possible health for herself and her fetus. At that time, blood glucose levels can be assessed closely and medication adjustments can be made to ensure optimal regulation before she becomes pregnant.

Crucial calories

Nutritional therapy is crucial in the treatment of women with diabetes. Typically, a 1,800- to 2,200-calorie diet is prescribed for the pregnant woman with diabetes. Alternatively, caloric requirements may be calculated at 30 to 35 kcal/kg of ideal body weight. The caloric requirement is usually divided among three meals and three snacks, allowing the calories to be distributed throughout the day in an attempt to maintain constant glucose levels. Additional dietary recommendations include reduced saturated fat and cholesterol and increased dietary fiber. Carbohydrates should make up 40% to 45% of daily caloric intake, with protein at 20% to 25%, and fat at 35% to 40% with mostly monosaturated and polyunsaturated fats. The goal is to allow a weight gain of approximately 25 to 35 lb (11.3 to 15.9 kg) for women with a normal prepregnancy weight, 15 to 25 lb (6.8 to 11.3 kg) for overweight women, 28 to 40 lb (12.7 to 18.2 kg) for underweight women, and 11 to 20 lb (5 to 9.1 kg) for obese women. This way, the neonate doesn’t grow too large and vaginal delivery remains a possibility.

Adjust, reduce, increase

For the woman with preexisting diabetes, insulin adjustments are necessary. Early in pregnancy, insulin may be reduced because of the increased use of glucose by the fetus for growth. However, later in pregnancy, an increase in insulin typically occurs because of an increase in the woman’s metabolism. Insulin therapy dosages and types are highly individualized. A continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion via a pump may be ordered to maintain constant blood glucose levels. The woman with gestational diabetes may require insulin if diet therapy doesn’t adequately control blood glucose levels.

Check 1: Glucose levels

To assist with blood glucose control, fingerstick blood glucose monitoring is important. For the woman with preexisting diabetes, typically this monitoring is performed daily, possibly as often as four times per day. For women with gestational diabetes, however, blood glucose monitoring may be performed only weekly. Regardless of monitoring frequency, the goal is to obtain fasting blood glucose levels below 95 mg/dl and 2-hour postprandial values below 120 mg/dl.

Check 2: Eyes and urinary tract

Throughout the pregnancy, follow-up monitoring is performed. A urine culture may be done each trimester to detect UTIs that

produce no symptoms. Ophthalmic examination is done at each trimester for the woman with preexisting diabetes and at least once during the pregnancy for the woman with gestational diabetes. Retinal changes may develop or progress during pregnancy.

Check 3: The fetus

Because the risk of fetal complications is high, fetal monitoring is crucial. A serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level may be done at 15 to 17 weeks’ gestation to assess for neural tube defects. Ultrasonography may be done at 18 to 20 weeks to detect gross abnormalities, and then be repeated at 28 weeks and again at 36 to 38 weeks to determine fetal growth, amniotic fluid volume, placental location, and biparietal diameter. At 36 weeks, the woman may undergo an amniocentesis to assess the lecithin-sphingomyelin ratio, an indicator of fetal maturity.

Preferred delivery route

In the past, delivery occurred at approximately week 37 of gestation via cesarean birth. More recently, however, vaginal delivery has become the preferred route of delivery. During labor, uterine contractions and FHR are monitored continuously. The mother’s glucose level is regulated with I.V. infusions of regular insulin based on blood glucose levels that are obtained hourly.

What to do

Carefully monitor the woman’s weight gain, blood glucose levels, and nutritional intake as well as fetal growth parameters throughout pregnancy.

Review results of fingerstick blood glucose monitoring; assess for signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia.

Assist with scheduling of follow-up laboratory studies, including glycosylated hemoglobin levels and urine studies as necessary.

Arrange for a consult with a dietitian.

Assist with preparations for labor, including explanations about possible labor induction and required monitoring.

Closely assess the woman in the postpartum period for changes in blood glucose levels and insulin requirements. Typically, the woman with preexisting diabetes will require no insulin in the immediate postpartum period (because insulin resistance is gone) and won’t return to her prepregnancy insulin requirements for several days. The woman with gestational diabetes usually exhibits normal blood glucose levels within 24 hours after delivery, requiring no further insulin or diet therapy.

Encourage the patient with gestational diabetes to keep all follow-up appointments so that glucose testing can be performed to detect possible type 2 diabetes.

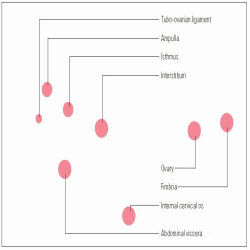

Ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the uterine cavity. It most commonly occurs in the fallopian tube but may occur in other sites as well. (See

Sites of ectopic pregnancy.’)Ectopic pregnancy occurs in 1.5% to 2% of pregnancies. The mortality rate has decreased to 0.5 deaths in 100,000. The prognosis for the patient is good with

prompt diagnosis, appropriate surgical intervention, and control of bleeding. Rarely, in cases of abdominal implantation, the fetus may survive to term. Usually, only one in three women who experience an ectopic pregnancy give birth to a live neonate in a subsequent pregnancy. Rupture of the tube causes life-threatening complications, including hemorrhage, shock, and peritonitis. Infertility results if the uterus, both fallopian tubes, or both ovaries are removed.

What causes it

Conditions that prevent or slow the fertilized ovum’s passage through the fallopian tube into the uterine cavity include:

endosalpingitis, an inflammatory reaction that causes folds of the tubal mucosa to agglutinate, narrowing the tube

diverticula (blind pouches that cause tubal abnormalities)

tumors pressing against the tube

previous surgery, such as tubal ligation or resection, or adhesions from previous abdominal or pelvic surgery

transmigration of the ovum from one ovary to the opposite tube resulting in delayed implantation.

Ectopic pregnancy may also result from congenital defects in the reproductive tract or ectopic endometrial implants in the tubal mucosa. Additional factors include sexually transmitted tubal infections as well as intrauterine devices that cause irritation of the cellular lining of the uterus and the fallopian tubes.

What to look for

Symptoms of ectopic pregnancy are sometimes similar to those of a normal pregnancy, making diagnosis difficult. Mild abdominal pain may occur, especially in cases of abdominal pregnancy. Typically, the patient reports amenorrhea or abnormal menses (in cases of fallopian tube implantation), followed by slight vaginal bleeding and unilateral pelvic pain over the mass. During a vaginal examination, the patient may report extreme pain when the cervix is moved and the adnexa is palpated. The uterus feels boggy and is tender. The patient may complain of lower abdominal pain precipitated by activities that increase abdominal pressure, such as a bowel movement. The patient may also experience referred pain in her right shoulder.

No time to waste

If the tube ruptures, the patient may complain of sharp lower abdominal pain, possibly radiating to the shoulders and neck. This condition is an emergency situation that requires immediate transport to a clinic or hospital.

What tests tell you

Differential diagnosis is necessary to rule out intrauterine pregnancy, ovarian cyst or tumor, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), appendicitis, and spontaneous abortion. The following tests confirm ectopic pregnancy:

Serum pregnancy test results show an abnormally low level of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) that remains lower than that in a normal intrauterine pregnancy when the test is repeated in 48 hours.

Real-time ultrasonography performed after a positive serum pregnancy test detects intrauterine pregnancy or ovarian cyst.

Culdocentesis (aspiration of fluid from the vaginal cul-de-sac) detects free blood in the peritoneum. This test is performed if ultrasonography detects the absence of a gestational sac in the uterus.

Laparoscopy, performed if culdocentesis is positive, may reveal pregnancy outside the uterus.

How it’s treated

If culdocentesis shows blood in the peritoneum, laparotomy and salpingectomy (excision of the fallopian tube) are indicated, possibly preceded by laparoscopy to remove the affected fallopian tube and control bleeding. Patients who wish to have children can undergo microsurgical repair of the fallopian tube. The ovary is saved, if possible; however, ovarian pregnancy requires oophorectomy. Interstitial pregnancy may require hysterectomy. Abdominal pregnancy requires a laparotomy to remove the fetus, except in rare cases, when the fetus survives to term or calcifies undetected in the abdominal cavity.

See ya, cells

Nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy involves oral administration of methotrexate (Folex), a chemotherapeutic drug and folic acid inhibitor that stops cell reproduction. The drug destroys remaining trophoblastic tissue, thus avoiding the need for laparotomy. This drug can be used if the patient has an unruptured ectopic pregnancy with a 3.5 cm size or less and if she is in stable condition. There also must be no cardiac motion, and no signs of intraabdominal bleeding, a blood disorder, kidney or liver disease.

Support, in short

Supportive treatment includes whole blood or packed red blood cells (RBCs) to replace excessive blood loss, broad-spectrum I.V. antibiotics for sepsis, supplemental iron (either oral or I.M.), and a high-protein diet. Grief counseling for the loss of a child is also recommended.

What to do

Ask the patient the date of her last menses, and obtain serum hCG levels as ordered.

Assess vital signs, and monitor vaginal bleeding for extent of fluid loss.

Check the amount, color, and odor of vaginal bleeding; monitor perineal pad count.

Withhold food and fluid orally in anticipation of possible surgery; prepare the patient for surgery as indicated.

Assess for signs and symptoms of hypovolemic shock secondary to blood loss from tubal rupture. Monitor closely for decreased urine output, which suggests fluid volume deficit.

Administer blood transfusions, as ordered, and provide emotional support.

Record the location and character of the pain, and administer analgesics as ordered.

Determine if the patient is Rh-negative. If she is, administer Rho(D) immune globulin (human), also known as RhoGAM, as ordered after treatment or surgery.

Provide a quiet, relaxing environment and encourage the patient and her partner to express their feelings of fear, loss, and grief. Help the patient to develop effective coping strategies.

To prevent recurrent ectopic pregnancy from diseases of the fallopian tube, urge the patient to get prompt treatment of pelvic infections.

Inform patients who have undergone surgery involving the fallopian tubes or those with confirmed PID that they’re at increased risk for another ectopic pregnancy.

Refer the patient to a grief counselor or support group.

Folic acid deficiency anemia

Folic acid deficiency anemia is a common, slowly progressive, megaloblastic (involving enlarged RBCs) form of anemia. Folic acid, or folacin, is a B vitamin needed for RBC formation and DNA synthesis. It’s also thought to play a role in preventing neural tube defects in the developing fetus.

Folic acid deficiency anemia is a risk factor in approximately 1% to 5% of pregnancies, becoming most apparent during the second trimester. It’s believed to be a risk factor contributing to early spontaneous abortion and abruptio placentae.

Folic folly

Folic acid is found in most body tissues. It acts as a coenzyme in metabolic processes. Although its body stores are relatively small, folic acid can be found in most wellbalanced diets. Even so, folic acid is watersoluble and is affected by heat, so it’s easily destroyed by cooking. Moreover, about 20% of folic acid intake is excreted unabsorbed. Insufficient intake—typically less than 50 mcg/day—usually results in folic acid deficiency anemia within 4 months.

What causes it

Alcohol abuse, which suppresses the metabolic effects of folic acid, is probably the most common cause of folic acid deficiency anemia. During pregnancy, folic acid deficiency anemia occurs most commonly in women with multiple pregnancy, probably

because of the increased fetal demand for folic acid. Folic acid deficiency anemia is also seen in women who have underlying hemolytic illness that results in rapid destruction and production of RBCs. In addition, certain drugs—such as phenytoin (Dilantin), an anticonvulsant agent that interferes with folate absorption, and hormonal contraceptives—have a role in folic acid deficiency anemia. Hemoglobin destruction can also be due to an inherited disorder such as sickle cell anemia.

What to look for

The main symptom of folic acid deficiency anemia is a history of severe, progressive fatigue. Associated findings include shortness of breath, palpitations, diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, headaches, forgetfulness, and irritability. The impaired oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood from lowered hemoglobin levels may produce complaints of weakness and light-headedness.

Assessment may reveal generalized pallor and jaundice. The patient may also appear wasted. Cheilosis (cracks in the corners of the mouth) and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue) may be present. Neurologic impairment is present only if the folic acid deficiency anemia is associated with a vitamin B12 deficiency.

What tests tell you

Typically, blood studies reveal:

macrocytic RBCs

decreased reticulocyte count

increased mean corpuscular volume

abnormal platelet count

decreased serum folate levels (below 4 mg/ml).

How it’s treated

During pregnancy, treatment consists primarily of folic acid supplements. Supplements may be given orally or parenterally (for patients who are severely ill, have malabsorption, or can’t take oral medication). In addition, a diet high in folic acid is urged. Many patients respond favorably to a wellbalanced diet.

What to do

Instruct the pregnant woman in the use of prescribed folic acid supplements and the need to continue taking them throughout pregnancy.

Assist with planning a well-balanced diet that includes meals and snacks that are high in folic acid.

Encourage the woman to eat or drink a rich source of vitamin C at each meal to enhance absorption of folic acid.

Administer a folic acid supplement as ordered throughout pregnancy, and assess for patient compliance. (See

Vitamin use.)

If the patient has severe anemia and requires hospitalization, plan activities, rest periods, and diagnostic tests to conserve energy. Monitor pulse rate often; if tachycardia occurs, the patient’s activities are too strenuous.

Monitor the patient’s complete blood count (CBC), platelet count, and serum folate levels as ordered.

Assess maternal vital signs and FHR as indicated.

Mild abruptio placentae (marginal separation) develops gradually and produces mild to moderate bleeding, vague lower abdominal discomfort, mild to moderate abdominal tenderness, and uterine irritability. Fetal heart tones remain strong and regular.

Mild abruptio placentae (marginal separation) develops gradually and produces mild to moderate bleeding, vague lower abdominal discomfort, mild to moderate abdominal tenderness, and uterine irritability. Fetal heart tones remain strong and regular. Moderate abruptio placentae (about 50% placental separation) may develop gradually or abruptly and produces continuous abdominal pain, moderate dark red vaginal bleeding, a tender uterus that remains firm between contractions, barely audible or irregular and bradycardic fetal heart tones and, possibly, signs of shock. Labor typically starts within 2 hours and usually proceeds rapidly.

Moderate abruptio placentae (about 50% placental separation) may develop gradually or abruptly and produces continuous abdominal pain, moderate dark red vaginal bleeding, a tender uterus that remains firm between contractions, barely audible or irregular and bradycardic fetal heart tones and, possibly, signs of shock. Labor typically starts within 2 hours and usually proceeds rapidly. Severe abruptio placentae (70% placental separation) develops abruptly and causes agonizing, unremitting uterine pain (described as tearing or knifelike); a boardlike, tender uterus; moderate vaginal bleeding; rapidly progressive shock; and absence of fetal heart tones (related to fetal cardiac distress). (See Placental separation in abruptio placentae.)

Severe abruptio placentae (70% placental separation) develops abruptly and causes agonizing, unremitting uterine pain (described as tearing or knifelike); a boardlike, tender uterus; moderate vaginal bleeding; rapidly progressive shock; and absence of fetal heart tones (related to fetal cardiac distress). (See Placental separation in abruptio placentae.) Type 1 diabetes (absolute insulin insufficiency) usually occurs before age 30, although it may occur at any age. The patient is typically thin and requires exogenous insulin and dietary management to achieve control.

Type 1 diabetes (absolute insulin insufficiency) usually occurs before age 30, although it may occur at any age. The patient is typically thin and requires exogenous insulin and dietary management to achieve control. Type 2 diabetes (insulin resistance with varying degrees of insulin secretory defects) usually occurs in obese adults after age 40. It’s treated with diet and exercise in combination with various antidiabetic drugs, although treatment may also include insulin therapy.

Type 2 diabetes (insulin resistance with varying degrees of insulin secretory defects) usually occurs in obese adults after age 40. It’s treated with diet and exercise in combination with various antidiabetic drugs, although treatment may also include insulin therapy. Gestational diabetes (diabetes that emerges during pregnancy) typically develops during the middle of the pregnancy when insulin resistance is most apparent.

Gestational diabetes (diabetes that emerges during pregnancy) typically develops during the middle of the pregnancy when insulin resistance is most apparent. Education edge

Education edge Education edge

Education edge Education edge

Education edge Education edge

Education edge