High-Risk Neonatal Conditions

In this chapter, you’ll learn:

characteristics of selected neonatal disorders

tests used to diagnose certain high-risk neonatal conditions

medical treatments and therapies for high-risk neonatal conditions

nursing interventions for high-risk neonatal conditions.

A look at the high-risk neonate

A neonate is considered to be high risk if he has an increased chance of dying during or shortly after birth or has a congenital or perinatal problem that requires prompt intervention. As medicine continues to develop more treatments for perinatal problems, high-risk neonates are more likely to survive. Many of these neonates have few or no residual effects from the crisis that marked their first hours after birth.

A shaky start

Parents of high-risk neonates may experience grief and difficulty coping as they adjust to their neonate’s condition. They may also feel a sense of loss and have difficulty bonding because their neonate isn’t the perfect, healthy baby they anticipated. The family of a neonate with a chronic illness or congenital anomaly must find ways to cope with long-term grief and develop strategies to provide the special care the condition will require (and perhaps to balance these care needs with those of other children). If the neonate is stillborn or dies within a few hours or days after birth, family members must complete their bonding with the neonate, then detach themselves gradually so they can focus again on the family’s life and needs.

|

Although the neonate’s condition dictates the specifics of nursing care, the main nursing goals for all high-risk neonates are to:

ensure oxygenation, ventilation, thermoregulation, nutrition, and fluid and electrolyte balance

prevent and control infection

encourage parent-neonate bonding

provide developmental care.

Drug addiction

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), there has been an increase in incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome infants noted between 2000 and 2009.

Neonatal drug addiction and its associated signs and symptoms of withdrawal result from addictive drug use by the neonate’s mother during pregnancy. As in all aspects of health care, care for the drug-addicted neonate should be provided in a nonjudgmental manner, especially because the neonate is an innocent victim of substance abuse by another person. Some of the medications, however, the mother may be able to account for and able to produce a legal prescription for.

|

Lowdown on drug effects

Pregnant women who use addictive drugs are at higher risk for:

abruptio placentae

spontaneous abortion

preterm labor

precipitous labor

psychotic responses.

Complications seen in the neonate may include:

urogenital malformations

cerebrovascular complications

low birth weight

decreased head circumference

respiratory problems

seizures

increase incidence of failure to thrive

death.

What causes it

Neonatal drug addiction can occur if the mother uses addictive drugs while pregnant. These drugs have teratogenic effects, causing abnormalities in embryonic or fetal development.

What to look for

Intrauterine drug exposure may cause obvious physical anomalies, neurobehavioral changes, or withdrawal. Signs and symptoms of a neonate’s drug dependence vary and may include physical and behavioral changes. These changes depend on:

specific drug or combination of drugs used

dosage

route of administration

metabolism and excretion by the mother and fetus

timing of drug exposure

length of drug exposure.

Benzodiazepines

Diazepam (Valium), a benzodiazepine, is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the world. It easily crosses the placental barrier to the fetus and is eliminated slowly by the fetus. Withdrawal signs and symptoms may appear hours to weeks after birth and may persist for months. Common signs and symptoms of withdrawal include:

hypothermia

hyperbilirubinemia

central nervous system (CNS) depression.

Opiates

Clinical presentation of opiate withdrawal in the neonate can last 2 to 3 weeks. Withdrawal signs and symptoms generally include dysfunction of the CNS and gastrointestinal (GI) system. (See Opiate withdrawal syndrome, page 532.)

Heroin

Neonates who have been exposed to heroin generally have low birth weights and are small for gestational age. They may also exhibit these signs and symptoms:

jitters and hyperactivity

shrill and persistent cry

frequent yawning or sneezing

increased deep tendon reflexes

decreased Moro reflex

poor feeding and sucking

increased respiratory rate

vomiting

diarrhea

hypothermia or hyperthermia

increased sweating

abnormal sleep cycle.

Opiate withdrawal syndrome

Be alert for these signs and symptoms of opiate withdrawal syndrome in the neonate.

Central nervous system

Seizures

Tremors

Irritability

Increased wakefulness

High-pitched cry

Increased muscle tone

Increased deep tendon reflexes

Increased Moro reflex

Increased yawning

Increased sneezing

Rapid changes in mood

Hypersensitivity to noise and external stimuli

Sleep disturbances

Sweating

GI system

Poor feeding

Uncoordinated and constant sucking— exaggerated

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Dehydration

Poor weight gain

Autonomic nervous system

Increased sweating

Nasal stuffiness

Fever

Mottling

Temperature instability

Increased respiratory rate

Increased heart rate

Methadone/Subutex

Withdrawal from methadone resembles that from heroin but tends to be more severe and prolonged. It includes:

increased incidence of seizures

disturbed sleep patterns

higher birth weight in neonates who are appropriate size for gestational age

higher risk of sudden infant death syndrome.

Marijuana

Neonates born to mothers who used marijuana while pregnant tend to be born at earlier gestations. An increased incidence of precipitous labor and meconium staining also occurs in this population of neonates. Neonates may exhibit tremors, jitteriness, and impaired sleep. When the mother abuses marijuana and alcohol during pregnancy, there’s a fivefold increase in the risk of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS).

|

Amphetamines

Women who use amphetamines while pregnant may have preterm neonates or neonates of low birth weight. Other characteristics these neonates may have include:

drowsiness

jitters

respiratory distress soon after birth

frequent infections

poor weight gain

emotional disturbances

delays in gross motor and fine motor development in early childhood

heart murmurs

transient bradycardia and tachycardia.

What tests tell you

The signs and symptoms of addiction and withdrawal may be mistaken for other common neonatal problems, especially if the mother’s drug use is unknown. You’ll need to differentiate between neonatal drug withdrawal and CNS irritability caused by infectious or metabolic disorders, such as hypoglycemia, hypomagnesemia, or hypocalcemia. You’ll also need to rule out hyperthyroidism, CNS hemorrhage, and anoxia.

Assessing the systems

The Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System is a scoring tool that can be used for term neonates. It assesses and scores areas of response in neonates with CNS, metabolic, vasomotor, respiratory, and GI disturbances. The current scoring system used is the Finnegan Score. The higher the overall score, the more likely the need for medication administration for withdrawal. Each institution has their medication administration protocol for the initiation of pharmacologic intervention and weaning. The test is repeated at specific intervals based on previous scores.

When it’s withdrawal

If the clinical signs and symptoms are consistent with drug withdrawal, obtain specimens of urine and meconium for drug testing. Meconium testing can detect drug use over a 20-week period. Be aware that urine screening may have a high false-negative rate because only neonates with recent exposure test positive. Also, keep in mind that although meconium drug testing isn’t conclusive if results are negative, this method is more reliable than urine testing. Umbilical cords may also be sent for analysis of maternal drug usage and is an accurate assessment.

How it’s treated

Initial treatment of the neonate who’s experiencing withdrawal should be supportive. This includes:

swaddling

holding the neonate

pacifiers

reducing environmental stimuli (lights, noise)

treated with a low lactose formula due to sensitivity

observing sleep habits

observing for temperature instability, weight gain or loss, or changes in clinical status that might suggest another disease process

fluid and electrolyte replacement

infection control

respiratory care.

Increase in skin care needed due to excessive breakdown secondary to loose stools.

|

Treating drugs with drugs

Indications for pharmacologic therapy include:

seizures

poor feeding

diarrhea

vomiting leading to weight loss and dehydration

inability to sleep

fever unrelated to infection.

increase in Finnegan scores based on the institutions protocol.

If pharmacologic therapy is needed, specific therapy from the same drug class is preferred. (See Drugs for withdrawal and Narcan and drug withdrawal.)

What to do

Nursing interventions for neonatal drug addiction include:

initiating preventive measures

identifying neonates at risk

assessing the neonate

providing supportive care

social service consult.

Stop addiction before it starts

Preventing maternal drug use is the ideal approach to eradicating the problem of neonatal drug addiction. Patient teaching and

support are essential. To identify a woman and neonate at risk for drug addiction:

support are essential. To identify a woman and neonate at risk for drug addiction:

Obtain a detailed maternal prescription and nonprescription drug history.

Assess the social habits of the parents.

Weighing the evidence

Weighing the evidenceNarcan and drug withdrawal

Over the years, it has become common practice to administer naloxone (Narcan) in the birthing room to a neonate who’s exhibiting CNS depression and whose mother recently received an opioid.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has determined that using naloxone is contraindicated in a neonate whose mother is a known or suspected opioid abuser because of the potential for neonatal seizures, which can develop as a result of the abrupt withdrawal of the drug.

Source: American Academy of Pediatrics. (1998). Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics, 101(6), 1079-1088.

Drugs for withdrawal

Drugs used to treat withdrawal include:

clonidine (Duraclon)

diazepam (Valium)

methadone (Dolophine)

morphine

phenobarbital

|

Screen those on the scene

To screen for drug exposure, perform maternal and neonatal assessments. Maternal findings that may indicate a need for neonatal drug testing include:

lack of prenatal care

previous unexplained fetal demise

precipitous labor

altered nutrition

abruptio placentae

hypertensive episodes

severe mood swings

stroke

myocardial infarction (MI)

recurrent spontaneous abortions.

Neonatal characteristics that may be associated with maternal drug use include:

preterm labor

cardiac defects

unexplained intrauterine growth retardation

neurobehavioral abnormalities

urogenital anomalies

atypical vascular incidents (stroke, MI, or necrotizing enterocolitis [NEC] in an otherwise healthy term neonate).

Ongoing neonatal assessment should include monitoring for changes in:

respiratory system

reflexes (including suck, swallow, and gag)

CNS

feeding and growth

vital signs.

Sending meconium, urine, or umbilical cord for toxicology analysis

Aiding the addicted

Supportive care of the neonate with a drug addiction includes:

maintaining the neonate’s airway

assessing breath sounds frequently

supporting and monitoring ventilation

providing supplemental oxygen

managing mechanical ventilation

making sure that resuscitative equipment is available

monitoring pulse oximetry (and capillary blood gas [CBG] studies if pulse oximetry is abnormally low)

decreasing CNS excitability by keeping the neonate tightly wrapped (swaddling)

offering a pacifier for nonnutritive sucking

using an undershirt with hand mittens to decrease facial scratching

aspirating nasal mucus as needed

organizing care to decrease stress due to handling

decreasing stimuli by reducing light in the room

monitoring the neonate with seizures

preventing trauma

administering medications as ordered

promoting rest

promoting nutritional intake

feeding in small, frequent amounts with the head elevated and the nipple positioned correctly so that sucking is effective

maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance

monitoring intake and output

giving supplemental fluids as ordered

evaluating serum electrolytes as ordered

maintaining skin integrity and providing skin care—especially to the diaper area

changing the neonate’s position

reporting signs of distress.

Fetal alcohol syndrome

A cluster of birth defects that are caused by in utero exposure to alcohol is referred to as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). It can result in abnormalities in the CNS, mental deficiencies, behavioral problems, growth retardation, and facial malformations.

What causes it

FAS is caused by the exposure of a fetus to alcohol in utero. Although prenatal alcohol exposure doesn’t always result in FAS, the safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy isn’t known. Alcohol crosses through the placenta and enters the fetal blood supply, and it can interfere with the healthy development of the fetus. In fact, birth defects associated with prenatal alcohol exposure can occur in the first 3 to 8 weeks of pregnancy, before a woman even knows she’s pregnant. Variables that affect the extent of damage caused to the fetus by alcohol include the amount of alcohol consumed, the timing of consumption, and the pattern of alcohol use.

What to look for

Affected neonates may display these signs within the first 24 hours of life:

difficulty establishing respirations

irritability

lethargy

seizure activity

tremulousness

opisthotonos

poor sucking reflex

abdominal distention

flat philtrum

wide set eyes

Overalls

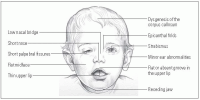

Overall signs of FAS include CNS dysfunction, abnormal development of the midline structures of the brain, growth deficiency, and a characteristic set of minor facial abnormalities that tend to normalize as the child grows. (See Common facial characteristics of FAS, page 538.)

Typical CNS problems for neonates with FAS may include:

mental retardation

microcephaly

poor coordination

decreased muscle tone

small brain

behavioral abnormalities

irritability

tremors

poor feeding.

Common facial characteristics of FAS

This illustration shows the distinct craniofacial features associated with FAS.

|

Growth deficiencies may manifest in a failure to thrive or a disproportionate decrease in adipose tissue. Length and weight in neonates with FAS typically measures 3% less than the average neonate.

|

Hits to the other systems

Abnormalities may also be seen in the cardiac system, skeletal system, urogenital system, and skin. Potential complications include:

cardiac murmurs

limited joint movement

finger and toe deformities

aberrant palmar creases

kidney defects

labial hypoplasia

hemangiomas.

As children and adults, individuals with FAS also commonly display:

defects in intellectual functioning

difficulties with memory, attention, and problem solving

learning disabilities

problems with mental health

difficulties with social interaction.

What tests tell you

Identifying clinical problems and assessment findings characteristic of FAS leads to diagnosis. Respiratory distress and neurologic dysfunction may be present. Feeding difficulties may also be noted. Radiographic studies may be used to reveal renal or cardiac defects.

How it’s treated

Treatment of FAS is supportive and depends on the individual neonate. The initial difficulties may be managed by preventing stimulation that may precipitate seizures, administering sedative or anticonvulsant medications, and providing supportive measures. Because the effects of alcohol in utero vary, care must be individualized to focus on the neonate’s specific abnormalities and deficits.

What to do

A fundamental nursing intervention for FAS is helping to prevent it. This can be achieved by:

increasing public awareness

increasing women’s access to prenatal care

providing educational programs

screening women of reproductive age for alcohol problems

using appropriate resources and strategies for decreasing alcohol use.

FASe out respiratory problems

Caring for neonates with FAS involves preventing or treating respiratory distress.

Place the neonate on a cardiac monitor and set the alarms.

Assess breath sounds frequently and be alert for signs of distress.

Suction as needed.

Place the neonate in a position in which he displays the least distress.

EmFASize nutrition

Special emphasis should be placed on following weight gain, assessing feeding behaviors, and devising strategies to increase nutritional intake.

Encourage feeding to promote bonding with the parents.

Elevate the neonate’s head during and after feeding.

Evaluate different nipples.

Burp the neonate well during and after feedings.

Monitor the neonate’s weight—may need higher calorie formulas to facilitate growth

Measure intake and output

Outpatient follow-up at a developmental clinic to assist in recognition of both behavioral and developmental problems.

FAScillitate bonding

To promote mother-neonate attachment:

Encourage visits.

Encourage physical contact.

Educate parents about the neonate’s complications.

Provide emotional support.

Gestational size variations

Whether they’re preterm, term, or postterm, neonates are classified by weight in three ways:

What causes it

Variations in gestational size are caused by different factors.

SGA neonates

Factors that can contribute to a neonate being SGA include:

congenital malformations

chromosomal anomalies

maternal infections

gestational hypertension

advanced maternal diabetes due to decreased blood flow to the placenta

intrauterine malnutrition due to poor placental function or maternal malnutrition

maternal smoking

maternal drug or alcohol use

multiple gestation.

LGA neonates

Neonates may become LGA because of genetic factors. For example, neonates tend to be larger if they’re male, if their parents are larger, or if the mother is a multipara. Neonates of mothers with diabetes also tend to be LGA because high maternal glucose levels stimulate continued insulin production by the fetus. This constant state of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia leads to excessive growth and fat deposition.

|

What to look for

Assessment findings depend on whether the neonate is SGA or LGA.

SGA neonates

SGA neonates are more likely to experience respiratory distress and hypoxia. They may also appear wide-eyed and alert at birth because of prolonged prenatal hypoxia. In addition, SGA neonates are prone to meconium aspiration because fetal hypoxia allows meconium to pass through a relaxed anal sphincter, thus causing the neonate to experience reflexive gasping. Hypoglycemia can occur in SGA neonates and can be noted from birth to day 4 of life. Decreased subcutaneous fat and a large ratio of body surface area to weight put the SGA neonate at risk for problems with thermoregulation.

LGA neonates

LGA neonates generally weigh more than 4,000 g (8 lb, 13 oz) and appear plump and full-faced. The LGA neonate may experience hypoxia during labor and be exposed to excessive trauma, such as fractures and intracranial hemorrhage, during vaginal delivery. Hypoglycemia may be noted at birth and during the transition period secondary to hyperinsulinemia. LGA which is secondary to infant of diabetic mother (IDM) have a higher risk for transposition of the great arteries, dextrocardia, left ventricular hypertrophy, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the Newborn (PPHN), and surfactant deficiency.

What tests tell you

Neonates of mothers with diabetes should have laboratory work to determine their hematocrit and glucose, calcium, and bilirubin levels. They should also be monitored for hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and respiratory distress syndrome (RDS).

How it’s treated

Treatment of gestational age size abnormalities varies depending on whether the neonate is SGA or LGA.

SGA neonates

Treatment of the SGA neonate should be supportive and individualized with nutrition being the primary focus. SGA neonates have higher caloric needs and benefit from frequent feedings. Care of the SGA neonate also includes glucose monitoring and careful respiratory assessments.

|

LGA neonates

During delivery of an LGA neonate, the mother may need additional help, such as an episiotomy, change in position, or the use of forceps or a vacuum. After birth, glucose monitoring and evaluation of jaundice is essential in LGA neonates. Risk for hypoglycemia is secondary to the hyperinsulinemia. Any birth traumas also need to be managed.

What to do

Nursing interventions for SGA and LGA neonates include:

supporting respiratory efforts—secondary to surfactant deficiency

providing a neutral thermal environment

protecting the neonate from infection

providing appropriate nutrition

maintaining adequate hydration

conserving the neonate’s energy

assessing glucose and calcium level

preventing skin breakdown

facilitating growth and development

keeping parents informed

providing support to the entire family.

Human immunodeficiency virus infection

Today, pregnant women have the opportunity to be tested for HIV. Such testing has led to an increase in the number of neonates known to be exposed to HIV, which in turn has allowed for early diagnosis and treatment.

What causes it

HIV can be transmitted to the neonate in one of three ways:

Risk factors for perinatal transmission can be either maternal or neonatal. (See Risk factors for perinatal transmission of HIV.)

|

What to look for

Most neonates exposed to HIV are born at term and are of AGA size. Normal physical findings are usually present. Physical findings, such as adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly, are absent at birth because HIV infection is believed to occur at delivery. These findings may develop later and suggest HIV infection.

What tests tell you

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends testing for HIV within 48 hours of birth, at age 1 to 2 months, and again at age 3 to 6 months. Two positive tests at different ages are required to make a positive diagnosis. Diagnostic tests used to detect HIV include HIV DNA polymerase chain reactions (PCR), HIV p24 antigen assay, HIV antibody, HIV culture, and immunologic testing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree