Hemodialysis

Hemodialysis is a potentially lifesaving procedure that removes blood from the body, circulates it through a purifying dialyzer, and then returns it to the body. Various access sites can be used for this procedure, and access can be temporary or long term depending on the patient’s requirements. Catheters are used for short-term access; for long-term access, arteriovenous (AV) fistulas are the preferred access because they last longer and are associated with fewer complications than other hemodialysis access sites.

The underlying mechanism in hemodialysis is differential diffusion across a semipermeable membrane, which extracts the by-products of protein metabolism (urea and uric acid) as well as creatinine and excess water. The membrane doesn’t permit diffusion of large molecules, such as blood cells and plasma proteins. This process restores or maintains the balance of the body’s buffer system and electrolytes, promoting a rapid return to normal serum values and helping to prevent complications associated with uremia. (See How hemodialysis works.)

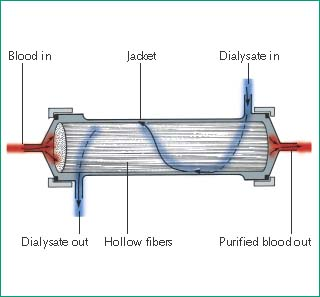

How Hemodialysis Works

In hemodialysis, blood flows from the patient to an external dialyzer (or artificial kidney) through an access site. Inside the dialyzer, blood and dialysate flow countercurrently, divided by a semipermeable membrane. The composition of the dialysate resembles normal extracellular fluid. The blood contains an excess of specific solutes (metabolic waste products and some electrolytes), and the dialysate contains electrolytes that may be at abnormal levels in the patient’s bloodstream. The dialysate’s electrolyte composition can be modified to raise or lower electrolyte levels, depending on need.

Excretory function and electrolyte homeostasis are achieved by diffusion, the movement of a molecule across the dialyzer’s semipermeable membrane from an area of higher solute concentration to an area of lower concentration. Water (solvent) crosses the membrane from the blood into the dialysate by ultrafiltration. This process removes excess water, waste products, and other metabolites through osmotic pressure and hydrostatic pressure. Osmotic pressure is the movement of water across the semipermeable membrane from an area of lesser solute concentration to one of greater solute concentration. Hydrostatic pressure forces water from the blood compartment into the dialysate compartment. Cleaned of impurities and excess water, the blood returns to the body through a venous site.

Types of Dialyzers

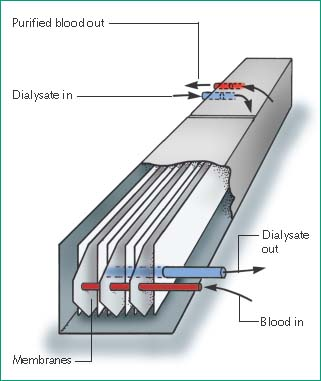

There are two types of dialyzers: the hollow-fiber and the flat-plate or parallel flow-plate. The hollow-fiber and flat-plate dialyzers may be used several times on each patient. Heparin is used to prevent clot formation during hemodialysis.

The hollow-fiber dialyzer, the most common type, contains fine capillaries, with a semipermeable membrane enclosed in a plastic cylinder. Blood flows through these capillaries as the system pumps dialysate in the opposite direction on the outside of the capillaries.

|

The flat-plate or parallel flow-plate dialyzer has two or more layers of semipermeable membrane, bound by a semirigid or rigid structure. Blood ports are located at both ends, between the membranes. Blood flows between the membranes, and dialysate flows in the opposite direction along the outside of the membranes.

|

Dialysate Delivery Systems

Three system types can be used to deliver dialysate. The batch system uses a reservoir for recirculating dialysate. The regenerative system uses sorbents to purify and regenerate recirculating dialysate. The proportioning system (the most common) mixes concentrate with water to form dialysate, which then circulates through the dialyzer and goes down a drain after a single pass, followed by fresh dialysate.

Hemodialysis provides temporary support for patients with acute, reversible renal failure as well as regular long-term treatment of patients with chronic end-stage renal disease. It may also be needed to remove toxic substances from the blood in cases of acute poisoning or barbiturate or analgesia overdose.

The patient’s condition, along with such variables as the rate of creatinine accumulation and weight gain, determines the number and duration of hemodialysis treatments. To determine the patient’s ultrafiltration requirements, the patient’s present weight is compared with his weight after his last dialysis treatment and his target weight.

Specially trained personnel typically perform this procedure in a hemodialysis unit. However, if the patient is acutely ill and unstable, hemodialysis may be performed at the bedside on the intensive care unit. Under special circumstances, hemodialysis may even be performed by the patient and his family at home.

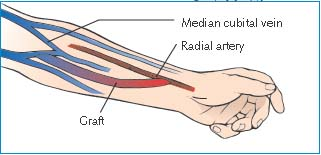

For dialysis access, a primary AV fistula is created by the surgical anastomosis of an artery and a vein. The veins and arteries of the arm must be carefully evaluated preoperatively to ensure adequate maturation and functioning of the fistula. Several different arterial-to-venous anastomotic sites can be used to create a fistula; the most commonly used is the radial artery to cephalic vein (Brescia-Cimino). A fistula may require weeks or months to mature and be usable for hemodialysis.

A patient whose vessels are inadequate for fistula construction may instead require an AV graft. In this procedure, a synthetic graft is surgically anastomosed to the selected artery and vein to form a bridge between them. The arm vessels are preferred, although leg vessels can be used. The graft material itself is cannulated during dialysis. Although some grafts may be used within days of their creation, most require several weeks of maturation before they can be used for dialysis. AV grafts have a higher incidence of thrombosis and infection than AV fistulas. (See Hemodialysis access sites.)

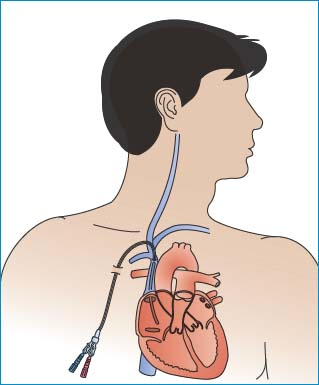

Several types of double-lumen catheters can be used for dialysis access depending on the patient’s condition, the doctor’s preference, and the anticipated length of time the catheter will be needed. The internal diameter of each lumen is approximately 12G to allow for high flow rates. The catheters have two ports—one colored red and one colored blue. The red port is used for withdrawing the patient’s blood and sending it to the dialyzer; the blue port is used for returning the dialyzed blood to the patient.

Typically, double-lumen catheters are placed in the internal jugular or subclavian veins. The femoral vein is used only when other sites are unavailable. The internal jugular site is preferable to the subclavian site in patients who already have or will have permanent dialysis accesses placed in their arms because venous thrombosis is a common complication of venous catheters. In a patient with a permanent arm access, such as a bridge graft or fistula, a subclavian vein thrombosis on the contralateral side may impede the venous outflow from the permanent dialysis access, rendering it unusable.

Most double-lumen catheters are considered temporary dialysis accesses. However, a double-lumen, tunneled catheter with a Dacron cuff may be used for months.3 This catheter is tunneled from the skin insertion site to the selected vein, and the Dacron cuff on the catheter under the skin acts as a barrier to infection.

Equipment

For General Dialysis and Initiating AV Access

Hemodialysis machine with appropriate dialyzer and dialysate ▪ two 16G winged fistula needles ▪ two 10-mL syringes ▪ prescribed flush solution ▪ linen-saver pad ▪ antiseptic swabs ▪ antiseptic solution ▪ sterile 4″ × 4″ gauze pads ▪ sterile 2″ × 2″ gauze pads ▪ sterile drape ▪ sterile and clean gloves, a gown, and a face shield ▪ stethoscope ▪ adhesive tape ▪ Optional: tourniquet.

For Initiating Dialysis with A Double-Lumen Catheter

Sphygmomanometer ▪ two 3-mL syringes ▪ two 5-mL syringes with prescribed anticoagulant flush ▪ syringe with prescribed anticoagulant.

For Discontinuing Dialysis with A Double-Lumen Catheter

Two 10-mL syringes with normal saline for injection ▪ two 5-mL syringes with prescribed anticoagulant flush ▪ two sterile luer-lock caps ▪ stethoscope ▪ sphygmomanometer ▪ antiseptic swabs and solution ▪ sterile drape ▪ sterile 4″ × 4″ sterile gauze pads ▪ two 5-mL syringes with prescribed anticoagulant flush.

Preparation of Equipment

Prepare the hemodialysis equipment following the manufacturer’s instructions and your facility’s protocol. To maintain catheter patency, carefully follow the manufacturer’s instructions for specific catheter care and flushing procedures. Maintain strict sterile technique to prevent introducing pathogens into the patient’s bloodstream during dialysis. Test the dialyzer and dialysis machine for residual disinfectant after rinsing and test all of the alarms.

Implementation

Initiating Hemodialysis

Gather and prepare the equipment.

Confirm the patient’s identity using at least two patient identifiers according to your facility’s policy.8

Check the doctor’s order.

Explain the procedure to the patient.

Weigh the patient. To determine his ultrafiltration requirements, compare his present weight to his weight after the last dialysis and his target weight. Record his baseline vital signs, and take his blood pressure while he’s sitting and standing.

Auscultate his heart for rate, rhythm, and abnormalities. Observe his respiratory rate, rhythm, and quality. Auscultate his lungs for crackles and any indication of possible fluid overload, and check for edema. Check his mental status, note any problems with his last dialysis treatment, and evaluate his previous laboratory data.

Help the patient into a comfortable position (supine or sitting in a recliner chair with his feet elevated). Make sure the access site is well supported and resting on a clean drape.

Hemodialysis Access Sites

Hemodialysis requires vascular access. The site and type of access may vary, depending on the expected duration of dialysis, the surgeon’s preference, and the patient’s condition.

Subclavian Vein Catheterization

Using the Seldinger technique, the doctor inserts an introducer needle into the subclavian vein. He then inserts a guide wire through the introducer needle and removes the needle. Using the guide wire, he then threads a 5″ to 12″ (13- to 30-cm) plastic or Teflon catheter with a Y hub into the patient’s vein.

|

Use of the subclavian vein for catheter placement isn’t recommended for patients who require permanent arteriovenous (AV) fistulas because the risk of thrombosis may compromise AV fistula creation.1

Femoral Vein Catheterization

Using the Seldinger technique, the doctor inserts an introducer needle into the left or right femoral vein. He then inserts a guide wire through the introducer needle and removes the needle.

Using the guide wire, he then threads either a 5″ to 12″ plastic or Teflon catheter with a Y hub, or two catheters, one for inflow and another placed about ½″ (1 cm) distal to the first for outflow. This catheter type should be used only when no other access site is available because it’s associated with an increased risk of infection and deep vein thrombosis.2

AV Fistula

To create a fistula, the surgeon makes an incision into the patient’s wrist or lower forearm, followed by a small incision in the side of an artery, and then another in the side of a vein. He sutures the edges of the incisions together to make a common opening 1/8″ to ¼″ (0.3 to 0.6 cm) long. Because an AV fistula requires a 4- to 6-week healing time before it can be used as a dialysis access site, it’s recommended that the fistula be created before hemodialysis is needed so that the fistula is healed and ready for use when needed.

AV Graft

To create an AV graft, the surgeon makes an incision in the patient’s forearm, upper arm, or thigh. He then tunnels a natural or synthetic graft under the skin and sutures the distal end to an artery and the proximal end to a vein.

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access