Hematologic and Immunologic care

Diseases

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

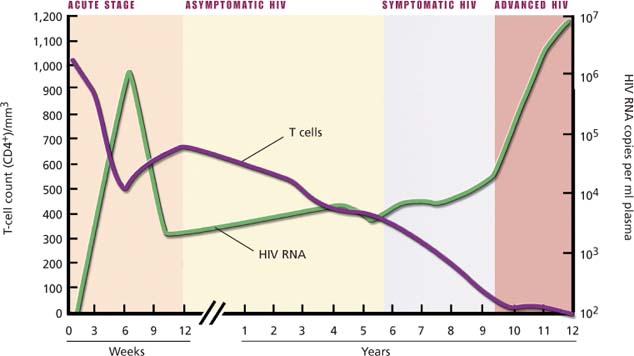

Currently one of the most widely publicized diseases, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is marked by progressive failure of the immune system. Although it’s characterized by gradual destruction of cell-mediated (T-cell) immunity, it also affects humoral immunity and even autoimmunity because of the central role of the CD4+ T lymphocyte in immune reactions. The resultant immunodeficiency makes the patient susceptible to opportunistic infections, unusual cancers, and other abnormalities that define AIDS.

A retrovirus—the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type I—is the primary causative agent. Transmission of HIV occurs by contact with infected blood or body fluids and is associated with identifiable high-risk behaviors. It’s therefore disproportionately represented in homosexual and bisexual men, I.V. drug users, neonates of HIV-infected women, recipients of contaminated blood or blood products (dramatically decreased since mid-1985), and heterosexual partners of people in the former groups. Because of similar routes of transmission, AIDS shares epidemiologic patterns with hepatitis B and sexually transmitted diseases.

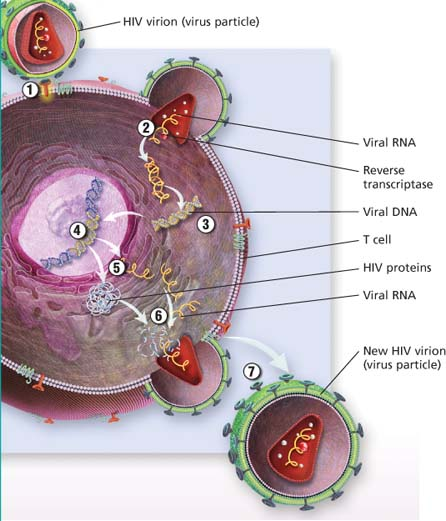

HIV life cycle

HIV life cycle

HIV binds to the T cell.

Viral RNA is released into the host cell.

Reverse transcriptase converts viral RNA into viral DNA.

Viral DNA enters the T cell’s nucleus and inserts itself into the T cell’s DNA.

The T cell begins to make copies of the HIV components.

Protease (an enzyme) helps create new virus particles.

The new HIV virion (virus particle) is released from the T cell.

|

HIV is transmitted by direct inoculation during intimate sexual contact, especially associated with the mucosal trauma of receptive rectal intercourse;

transfusion of contaminated blood or blood products (a risk diminished by routine testing of all blood products); sharing of contaminated needles; and transplacental or postpartum transmission from infected mother to fetus (by cervical or blood contact at delivery and in breast milk).

transfusion of contaminated blood or blood products (a risk diminished by routine testing of all blood products); sharing of contaminated needles; and transplacental or postpartum transmission from infected mother to fetus (by cervical or blood contact at delivery and in breast milk).

HIV isn’t transmitted by casual household or social contact. The average time between exposure to the virus and diagnosis of AIDS is 8 to 10 years, but shorter and longer incubation times have been recorded. Most people develop antibodies within 6 to 8 weeks of contracting the virus.

Signs and symptoms

Mononucleosis-like syndrome, which may be attributed to a flu or other virus and then may remain asymptomatic for years (after a high-risk exposure and inoculation); in the latent stage, laboratory evidence of seroconversion only sign of HIV infection

When signs and symptoms appear, they may take many forms:

Persistent generalized adenopathy

Weight loss, fatigue, night sweats, fevers (nonspecific signs and symptoms)

Neurologic symptoms resulting from HIV encephalopathy, such as memory loss, partial paralysis, loss of coordination

Opportunistic infection or cancer

Diarrhea

Stages of HIV infection

1. Primary stage

This stage occurs about 1 to 2 weeks after initial infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). During this stage, the virus undergoes massive replication. Patients may be asymptomatic or have a flulike syndrome.

2. Asymptomatic HIV

During this stage, also called the clinical latency stage, chronic signs or symptoms aren’t present. T-cell count may be used to monitor the progression of the disease. With the patient’s own resistance and drug therapy, this stage can last 8 years or longer.

3. Symptomatic HIV

This stage has two phases: early and late. When the T-cell count in blood falls below 200 cells/mm3, it’s the late phase. This stage of HIV infection is defined mainly by the emergence of opportunistic infections and cancers to which the immune system normally helps maintain resistance.

Treatment

No cure; however, the World Health Organization recommends treatment for patients with CD4+ counts of 350 cells/mm3 or less, regardless of clinical stage. Primary therapy for HIV infection includes these types of antiretroviral agents:

protease inhibitors (PIs), such as ritonavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, and atazanavir

nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), such as tenofovir, emtricitabine, zidovudine, didanosine, zalcitabine, lamivudine, and stavudine

nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), such as efavirenz, nevirapine, and delavirdine.

Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), such as raltegravir and elvitegravir

Immunomodulators designed to boost the weakened immune system

Anti-infective and antineoplastic agents to combat opportunistic infections and associated cancers

Treatment protocols combining two or more agents that typically include one PI plus two NNRTIs, two NRTIs plus one NNRTI, or one INSTI plus two NRTIs

Other NRTIs, such as didanosine and zalcitabine in combination regimens for patients who can’t tolerate or no longer respond to zidovudine

Nursing considerations

Recognize that a diagnosis of AIDS is profoundly distressing because of the disease’s social impact and the discouraging prognosis. The patient may lose his job and financial security as well as the support of his family and friends. Coping with an altered body image, the emotional burden of a serious illness, and the threat of death may overwhelm the patient.

Monitor the patient for fever, noting any pattern, and for signs of skin breakdown, cough, sore throat, and diarrhea. Assess him for swollen, tender lymph nodes, and check laboratory values regularly, especially CD41 counts and viral loads.

Avoid glycerine swabs for mucous membranes, and have the patient use normal saline or bicarbonate mouthwash for daily oral rinsing.

Record the patient’s caloric intake.

Ensure adequate fluid intake during episodes of diarrhea.

Provide meticulous skin care, especially if the patient is debilitated.

Encourage the patient to maintain as much physical activity as he can tolerate. Make sure his schedule includes time for both exercise and rest.

If the patient develops Kaposi’s sarcoma, monitor the progression of lesions.

Monitor opportunistic infections or signs of disease progression, and treat infections as ordered.

Note that a patient who also has hepatitis or tuberculosis may have different regimens or start treatments at different points.

Teaching about AIDS

Teaching about AIDS

Explain that poor drug compliance may lead to resistance and treatment failure. Help the patient understand that medication regimens must be followed closely and may be required for many years, if not throughout life.

Urge the patient to inform potential sexual partners and health care workers that he has HIV infection.

Teach the patient how to identify the signs of impending infection, and stress the importance of seeking immediate medical attention.

Involve the patient with hospice care early in treatment so he can establish a relationship.

If the patient develops acquired immunodeficiency syndrome dementia in stages, help him understand the progression of this symptom.

Provide information regarding support services.

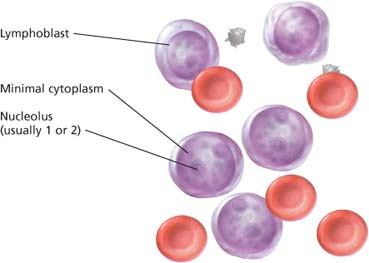

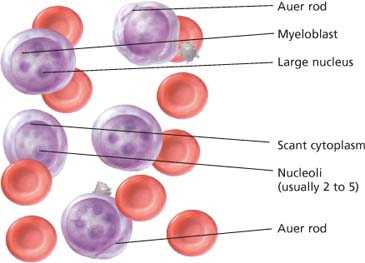

Acute leukemia

Acute leukemia begins as a malignant proliferation of white blood cell (WBC) precursors, or blasts, in bone marrow or lymph tissue. It results in an accumulation of these cells in peripheral blood, bone marrow, and body tissues.

The most common forms of acute leukemia include acute lymphoblastic (lymphocytic) leukemia (ALL), characterized by abnormal growth of lymphocyte precursors (lymphoblasts); acute myeloblastic (myelogenous) leukemia (AML), which causes rapid accumulation of myeloid precursors (myeloblasts); and acute monoblastic (monocytic) leukemia, or Schilling’s type, which results in a marked increase in monocyte precursors (monoblasts). Other variants include acute myelomonocytic leukemia and acute erythroleukemia.

Untreated, acute leukemia is invariably fatal, usually because of complications resulting from leukemic cell infiltration of bone marrow or vital organs. With treatment, the prognosis varies.

With ALL, treatment induces remission in 95% of children (average survival time: 5 years) and in 65% of adults (average survival time: 1 to 2 years). Children between ages 2 and 8 have the best survival rate—about 50%—with intensive therapy.

With AML, the average survival time is only 1 year after diagnosis, even with aggressive treatment. Remission lasting 2 to 10 months occurs in 50% of children; adults survive only about 1 year after diagnosis, even with treatment. Duration of remission is linked to age; younger patients have a greater chance of obtaining remission.

The exact cause of acute leukemia is unknown; however, radiation (especially prolonged exposure), certain chemicals and drugs, viruses, genetic abnormalities, and chronic exposure to benzene are likely contributing factors.

Although the pathogenesis isn’t clearly understood, immature, nonfunctioning WBCs appear to accumulate first in the tissue where they originate (lymphocytes in lymph tissue, granulocytes in bone marrow). These immature WBCs then spill into the bloodstream. They then overwhelm the red blood cells (RBCs) and the platelets. From there, immature white blood cells infiltrate other tissues.

Signs and symptoms

High fever

Abnormal bleeding

Fatigue

Night sweats

Weakness and lassitude

Recurrent infections

Chills

Abdominal or bone pain (ALL, AML, or acute monoblastic leukemia)

Tachycardia

Decreased ventilation

Palpitations

Systolic ejection murmur

Pallor

Lymph node enlargement

Liver or spleen enlargement

Treatment

Intrathecal instillation of methotrexate or cytarabine with cranial radiation (for meningeal infiltration)

Vincristine, prednisone, high-dose cytarabine, and daunorubicin (for ALL); intrathecal methotrexate or cytarabine (because ALL carries a 40% risk of meningeal infiltration); radiation therapy for brain or testicular infiltration, which may occur with ALL

Combination I.V. daunorubicin and cytarabine (for AML); other treatments after failure of this combination to induce remission, including a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, or methotrexate; high-dose cytarabine alone or with other drugs; amsacrine; etoposide; and 5-azacytidine and mitoxantrone

Cytarabine and thioguanine with daunorubicin or doxorubicin (for acute monoblastic leukemia)

Antibiotic, antifungal, and antiviral drugs and granulocyte injections to control infection

Blood transfusions of platelets, to prevent bleeding, and of RBCs, to prevent anemia

Bone marrow transplantation (for some patients)

Colony-stimulating factors such as granulocyte-macrophage to boost the bone marrow’s response and decrease the duration of granulocytopenia after induction therapy.

Nursing considerations

Before treatment begins, help establish an appropriate rehabilitation program for the patient during remission.

Watch for signs of meningeal infiltration (confusion, lethargy, and headache).

Check the lumbar puncture site often for bleeding.

Take steps to prevent hyperuricemia, a possible result of rapid, chemotherapy-induced leukemic cell lysis.

If the patient receives daunorubicin or doxorubicin, watch for early indications of cardiotoxicity, such as arrhythmias and signs of heart failure.

Keep the patient’s skin and perianal area clean, apply mild lotions or creams to keep the skin from drying and cracking, and thoroughly clean the skin before all invasive skin procedures.

Monitor the patient’s temperature every 4 hours. Report a temperature rise over 101° F (38.3° C).

Watch for bleeding. Avoid giving aspirin or aspirin-containing drugs or rectal suppositories, taking a rectal temperature, performing a digital rectal examination, or administering I.M. injections.

After bone marrow transplantation, administer antibiotics, and transfuse packed RBCs as necessary.

Administer prescribed pain medications as needed, and monitor their effectiveness.

Control mouth ulceration by checking often for obvious ulcers and gum swelling and by providing frequent mouth care and saline rinses.

Minimize stress by providing a calm, quiet atmosphere that’s conducive to rest and relaxation.

Teaching about acute leukemia

Teaching about acute leukemia

Explain the course of the disease to the patient.

Teach the patient and his family how to recognize signs and symptoms of infection (fever, chills, cough, sore throat). Tell them to report an infection to the practitioner.

Explain to the patient that his blood may not have enough platelets for proper clotting, and teach him the signs of abnormal bleeding (bruising, petechiae). Explain that he can apply pressure and ice to the area to stop such bleeding. Teach him steps he can take to prevent bleeding. Urge him to report excessive bleeding or bruising to the practitioner.

Inform the patient that drug therapy is tailored to his type of leukemia. Explain that he’ll probably need a combination of drugs; teach him about the ones he’ll receive. Make sure he understands their adverse effects and the measures he can take to prevent or alleviate them.

Explain that if the chemotherapy causes weight loss and anorexia, the patient will need to eat and drink high-calorie, high-protein foods and beverages.

Instruct the patient to use a soft toothbrush and to avoid hot, spicy foods and commercial mouthwashes, which can irritate the mouth ulcers that result from chemotherapy.

If the patient receives cranial radiation, explain what the treatment is and how it will help him. Be sure to discuss potential adverse effects and the steps he can take to minimize them.

If the patient needs a bone marrow transplant, reinforce the practitioner’s explanation of the treatment, its possible benefits, and the potential adverse effects.

Advise the patient to limit his activities and to plan rest periods during the day.

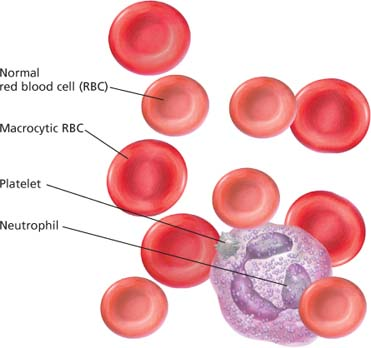

Aplastic and hypoplastic anemias

Aplastic and hypoplastic anemias are potentially fatal and result from injury to or destruction of stem cells in bone marrow or the bone marrow matrix, causing pancytopenia (anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia) and bone marrow hypoplasia.

Aplastic anemias usually develop when damaged or destroyed stem cells inhibit red blood cell (RBC) production. Less commonly, they develop when damaged bone marrow microvasculature creates an unfavorable environment for cell growth and maturation. About one-half of such anemias result from drugs (such as chloramphenicol), toxic agents (such as benzene), or radiation. The rest may result from immunologic factors (suspected but unconfirmed), severe disease (especially hepatitis), viral infection (especially in children), and preleukemic and neoplastic infiltration of bone marrow.

Causes of acquired aplastic anemias

Drugs, toxic agents, and radiation cause about one-half of all cases of acquired aplastic anemias. Examples and other causes are listed here.

Drugs

Antiarrhythmics (procainamide), antibiotics (chloramphenicol, cephalosporins, sulfonamides and, rarely, penicillins), anticonvulsants (especially phenytoin, ethosuximide, and carbamazepine), antidiabetics, anti-inflammatory drugs (phenylbutazone, indomethacin, gold, and penicillamine), antimalarials, antineoplastics, antithyroid drugs, diuretics (including hydrochlorothiazide), phenothiazines, zidovudine

Chemicals and toxins

Aromatic hydrocarbons (benzene), heavy metals, pesticides

Infections

Cytomegalovirus, hepatitis C, Epstein-Barr virus, miliary tuberculosis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis

Rheumatoid and autoimmune diseases

Graft-versus-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis

Other causes

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, pregnancy, idiopathic causes, radiation, thymoma

Signs and symptoms

Progressive weakness and fatigue

Shortness of breath

Headache

Easy bruising and bleeding (especially from the mucous membranes [nose, gums, rectum, vagina])

Pallor (with anemia)

Ecchymosis, petechiae, or retinal bleeding (with thrombocytopenia)

Bibasilar crackles, tachycardia, and a gallop murmur (with anemia resulting in heart failure)

Opportunistic infections, such as fever, oral and rectal ulcers, and sore throat

Treatment

Packed RBC and platelet transfusions

Human leukocyte antigen-matched leukocytes or antithymocyte globulin used alone or with cyclosporine (improves outcomes for children and severely neutropenic patients)

Bone marrow transplantation, preferably from a human leukocyte antigen–matched sibling (for anemia resulting from severe aplasia and for those needing constant RBC transfusions)

Frequent hand washing and air flow filtration to prevent infection

Antibiotics (for infection; however, they aren’t given prophylactically because they tend to encourage resistant strains of organisms)

Respiratory support with oxygen and blood transfusions (for low hemoglobin levels)

An immunosuppressant (if patient isn’t responding to other therapy)

Colony-stimulating factors (agents that encourage the growth of specific cellular components, including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and erythropoietic stimulating factor

Nursing considerations

Focus your efforts on helping to prevent or manage hemorrhage, infection, and adverse reactions to drug therapy or blood transfusion.

If the patient’s platelet count is low (less than 20,000/μl), prevent hemorrhage by avoiding I.M. injections, suggesting the use of an electric razor and a soft toothbrush, humidifying oxygen to prevent drying of mucous membranes (dry mucosa may bleed), and promoting regular bowel movements through the use of a stool softener and a diet to prevent constipation (which can cause rectal mucosal bleeding). Detect bleeding early by checking for blood in urine and stool and assessing skin for petechiae.

Make sure that throat, urine, nasal, stool, and blood cultures are done regularly and correctly to check for infection.

If the patient has a low hemoglobin level, which causes fatigue, schedule frequent rest periods. Administer oxygen therapy as needed.

Ensure a comfortable environmental temperature for a patient experiencing hypothermia or hyperthermia.

If a blood transfusion is necessary, assess the patient for a transfusion reaction by checking his temperature and watching for the development of other signs and symptoms, such as rash, urticaria, pruritus, back pain, restlessness, and shaking chills.

Be sure to monitor blood studies carefully in the patient receiving an anemia-inducing drug, to prevent aplastic anemia.

Teaching about aplastic anemia

Teaching about aplastic anemia

Teach the patient to avoid contact with potential sources of infection, such as crowds, soil, and standing water, which can harbor organisms.

Reassure and support the patient and his family by explaining the disease and its treatment, particularly if the patient has recurring acute episodes. Explain the purpose of all prescribed drugs, and discuss possible adverse reactions, including those he should report promptly.

Review signs and symptoms of bleeding and when to seek medical attention.

Tell the patient who doesn’t require hospitalization that he can continue his normal lifestyle with appropriate restrictions (such as regular rest periods) until remission occurs.

Refer the patient to the Aplastic Anemia Foundation and MDS International Foundation for additional information and assistance.

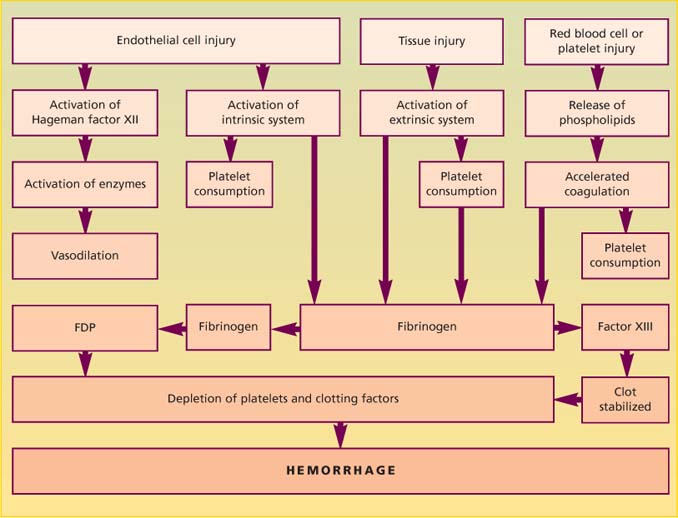

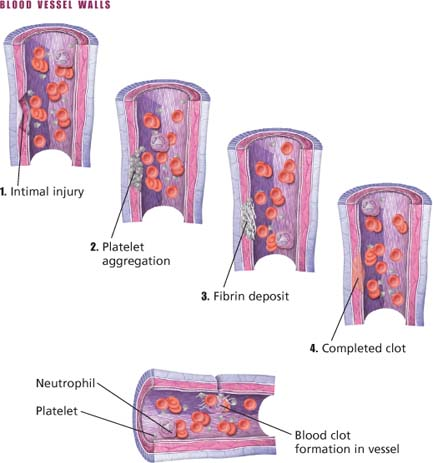

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is also known as consumption coagulopathy and defibrination syndrome. DIC occurs as a complication of diseases and conditions that accelerate clotting, causing thrombosis of small blood vessels, organ necrosis, depletion of circulating clotting factors and platelets, and activation of the fibrinolytic system. This, in turn, can provoke severe hemorrhage.

Clotting in the microcirculation usually affects the kidneys and extremities but can occur in the brain, lungs, pituitary and adrenal glands, and GI mucosa. Other conditions, such as vitamin K deficiency, hepatic disease, and anticoagulant therapy, can cause similar hemorrhage.

DIC is usually acute but can be chronic for patients with cancer. The prognosis depends on early detection and treatment, the severity of the hemorrhage, and treatment of the underlying disease or condition.

DIC may result from:

infection (most common cause)—gram-negative or gram-positive septicemia; viral, fungal, or rickettsial infection; protozoal infection

obstetric complications—abruptio placentae, amniotic fluid embolism, retained dead fetus, eclampsia, septic abortion, postpartum hemorrhage

neoplastic disease—acute leukemia, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma

a disorder that produces necrosis—extensive burns and trauma, brain tissue destruction, transplant rejection, hepatic necrosis, anorexia

another disorder or condition—heatstroke, shock, poisonous snakebite, cirrhosis, fat embolism, incompatible blood transfusion, a drug reaction, cardiac arrest, surgery necessitating cardiopulmonary bypass, giant hemangioma, extensive venous thrombosis, purpura fulminans, adrenal disease, acute respiratory distress syndrome, diabetic ketoacidosis, pulmonary embolism, or sickle cell anemia.

Why such conditions and disorders lead to DIC is unclear, as is whether they lead to DIC through a common mechanism. In many patients, the triggering mechanisms may be the entrance of foreign protein into the circulation and vascular endothelial injury.

Regardless of how DIC begins, the typical accelerated clotting results in generalized activation of prothrombin and a consequent excess of thrombin. Excess thrombin converts fibrinogen to fibrin, producing fibrin clots in the microcirculation. This process consumes exorbitant amounts of coagulation factors (especially platelets, factor V, prothrombin, fibrinogen, and factor VIII), causing thrombocytopenia, deficiencies in factors V and VIII, hypoprothrombinemia, and hypofibrinogenemia.

Circulating thrombin activates the fibrinolytic system, which lyses fibrin clots into fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs). The hemorrhage that occurs may result largely from the anticoagulant activity of FDPs as well as from depletion of plasma coagulation factors.

Three mechanisms of DIC

However disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) begins, accelerated clotting (characteristic of DIC) usually results in excess thrombin, which in turn causes fibrinolysis with excess fibrin formation and fibrin degradation products (FDPs), activation of fibrin-stabilizing factor (factor XIII), consumption of platelet and clotting factors and, eventually, hemorrhage.

|

Signs and symptoms

Abnormal bleeding without a history of a serious hemorrhagic disorder (usually the first sign)

Signs of bleeding into the skin, such as cutaneous oozing, petechiae, ecchymoses, and hematomas

Excessive bleeding from I.V. sites

Nausea and vomiting

Chest pain

Hemoptysis

Epistaxis

Seizures

Oliguria

Severe muscle, back, and abdominal pain

Acrocyanosis

Dyspnea

Diminished peripheral pulses

Decreased blood pressure

Mental status changes, including confusion

Treatment

Recognition and treatment of cause of DIC

Blood, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, or packed red blood cell transfusions to support hemostasis (for active bleeding)

Heparin therapy (remains controversial); administered (in most cases) with transfusion therapy; in early stages to prevent microclotting; as a late resort for active bleeding; mandatory if thrombosis occurs

Drugs such as antithrombin III to inhibit clotting cascade

Nursing considerations

Focus on early recognition of signs of abnormal bleeding, prompt treatment of the underlying disorders, and prevention of further bleeding.

Keep the family informed of the patient’s progress. Prepare them for his appearance (I.V. lines, nasogastric tubes, bruises, dried blood). Give emotional support. Listen to the patient’s and family’s concerns. When possible, encourage the patient. As needed, enlist the aid of a social worker, a chaplain, and other health care team members in providing support.

If the patient can’t tolerate activities because of blood loss, provide rest periods.

Administer the prescribed analgesic for pain as needed.

Reposition the patient every 2 hours, and provide meticulous skin care to prevent skin breakdown.

Administer oxygen therapy as ordered.

Test stool and urine for occult blood.

To prevent clots from dislodging and causing fresh bleeding, don’t vigorously rub these areas when washing. Use a 1:1 solution of hydrogen peroxide and water to help remove crusted blood.

Protect the patient from injury. Enforce complete bed rest during bleeding episodes. If the patient is agitated, pad the side rails.

If bleeding occurs, use pressure and topical hemostatic agents, such as absorbable gelatin sponges (Gelfoam), microfibrillar collagen hemostat (Avitene Hemostat), or thrombin (Thrombinar), to control it.

Check all venipuncture sites frequently for bleeding.

Monitor intake and output hourly in patients with acute DIC, especially when administering blood products.

Watch for bleeding from the GI and genitourinary (GU) tracts. If you suspect intra-abdominal bleeding, measure the patient’s abdominal girth at least every 4 hours and monitor closely for signs of shock. Perform bladder irrigations, as ordered, for GU bleeding.

Monitor the results of serial blood studies (particularly hematocrit, hemoglobin level, coagulation times, and fibrin split products and fibrinogen levels).

Teaching about DIC

Teaching about DIC

Explain disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) to the patient and his family.

Teach them about the signs and symptoms of DIC, the diagnostic tests required, and the treatment that the patient is to receive.

Explain that injury can cause bleeding. Tell the patient to exercise caution when moving to avoid bumping into the bed or other objects.

Advise the patient to take frequent rest periods.

Hemophilia

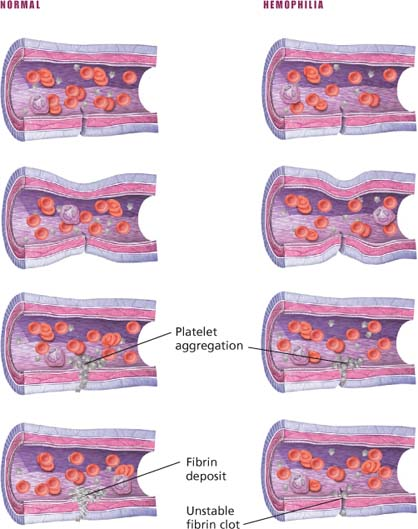

A hereditary bleeding disorder, hemophilia results from deficiency of specific clotting factors. Hemophilia A (classic hemophilia), which affects more than 80% of all hemophiliacs, results from deficiency of factor VIII; hemophilia B (Christmas disease), which affects 15% of hemophiliacs, results from deficiency of factor IX. Other evidence suggests that hemophilia may result from nonfunctioning factors VIII and IX, rather than from deficiency of these factors.

Hemophilia produces abnormal bleeding, which may be mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the degree of factor deficiency. After a hemophiliac forms a platelet plug at a bleeding site, the lack of clotting factors impairs formation of a stable fibrin clot. Immediate hemorrhage isn’t prevalent, but delayed bleeding is common.

Signs and symptoms

Pain and swelling in a weight-bearing joint, such as the hip, knee, and ankle

Bleeding after circumcision (usually the first sign)

Spontaneous bleeding or severe bleeding after minor trauma that may produce large subcutaneous and deep intramuscular hematomas

Abdominal, chest, or flank pain, indicating internal bleeding

Hematuria or hematemesis

Tarry stools

Hematomas on the extremities, the torso, or both

Limited joint range of motion

Treatment

Careful management by a hematologist (for patients undergoing surgery)

Replacement of the deficient factor before and after surgery (even for minor surgery such as dental extraction)

Aminocaproic acid (for oral bleeding, to inhibit the active fibrinolytic system in oral mucosa)

Hemophilia A

Cryoprecipitated antihemophilic factor (AHF), lyophilized AHF, or both in doses large enough to raise clotting factor levels above 25% of normal to permit normal hemostasis

AHF before surgery to raise clotting factors to hemostatic levels until wound heals; fresh frozen plasma administration (has some drawbacks)

Inhibitors to factor VIII develop after multiple transfusions in 10% to 20% of patients with severe hemophilia, rendering the patient resistant to factor VIII infusions

Desmopressin to stimulate the release of stored factor VIII, raising the level in the blood

Hemophilia B

Administration of factor IX concentrate during bleeding episodes to increase factor IX levels

Recognizing and managing bleeding

In patients with hemophilia, bleeding may occur spontaneously or stem from an injury. Inform your patient and his family about possible types of bleeding and their associated signs and symptoms. Accordingly, advise them which actions to take and when to call for medical help.

| Bleeding site | Signs and symptoms | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Intracranial | Change in personality or level of consciousness, headache, nausea | Instruct the patient or his family to notify the practitioner immediately and to treat symptoms as an emergency. |

| Joints (hemarthroses) Usually the knees, followed by elbows, ankles, shoulders, hips, and wrists | Joint pain and swelling, joint tingling and warmth (at onset of hemorrhage) | Tell the patient to begin antihemophilic factor (AHF) infusions and then to notify the practitioner. |

| Kidney | Pain in the lower back near the waist, decreased urine output | Instruct the patient to notify the practitioner and to start AHF infusion if bleeding results from a known recent injury. |

| Muscles | Pain and reduced function of the affected muscle; tingling, numbness, or pain in a large area away from the affected site (referred pain) | Urge the patient to notify the practitioner and to start an AHF infusion if the patient is reasonably certain that bleeding results from recent injury (otherwise, call the practitioner for instructions). |

| Subcutaneous tissue or skin | Pain, bruising, and swelling at the site (delayed oozing may also occur after an injury) | Show the patient how to apply appropriate topical agents, such as ice packs and absorbable gelatin sponges (Gelfoam), to stop bleeding. |

| Heart (cardiac tamponade) | Chest tightness, shortness of breath, swelling (usually occurs in patients who are very young or who have severe disease) | Instruct the patient to contact the practitioner or to go to the nearest emergency department immediately. |

Nursing considerations

Provide emotional support, and listen to the patient’s fears and concerns.

Watch for signs and symptoms of decreased tissue perfusion.

Monitor the patient’s blood pressure and pulse and respiratory rates. Observe him frequently for bleeding from the skin, mucous membranes, and wounds.

During bleeding episodes

If the patient has surface cuts or epistaxis, apply pressure—usually the only treatment needed.

With deeper cuts, pressure may stop the bleeding temporarily. Cuts deep enough to require suturing may also require factor infusions to prevent further bleeding.

Give the deficient clotting factor or plasma as ordered.

Apply cold compresses or ice bags, and elevate the injured part.

To prevent recurrence of bleeding, restrict activity for 48 hours after bleeding is under control.

Control pain with an analgesic, such as acetaminophen, propoxyphene, codeine, or morphine as ordered. Avoid I.M. injections. Aspirin and aspirin-containing medications are contraindicated.

If the patient can’t tolerate activities because of blood loss, provide rest periods between activities.

Bleeding into a joint

Immediately elevate the joint.

To restore joint mobility, if ordered, begin range-of-motion exercises at least 48 hours after the bleeding is controlled. Tell the patient to avoid weight bearing until bleeding stops and swelling subsides.

Administer an analgesic for pain. Also, apply ice packs and elastic bandages to alleviate the pain.

After bleeding episodes and surgery

Watch closely for signs and symptoms of further bleeding, such as increased pain and swelling, fever, and symptoms of shock.

Closely monitor partial thromboplastin time.

Teaching about hemophilia

Teaching about hemophilia

Teach the patient the benefits of regular exercise. Explain that isometric exercises can also help to prevent muscle weakness and recurrent joint bleeding. Refer him for physical therapy as indicated.

Advise parents to protect their child from injury while avoiding unnecessary restrictions that impair his normal development. An older child must not participate in contact sports, such as football, but he can be encouraged to swim or play golf.

Tell the patient to avoid such activities as lifting heavy items and using power tools because they increase the risk of injury that can result in serious bleeding problems.

If an injury occurs, direct the parents to apply cold compresses or ice bags and elevate the injured part or to apply light pressure to the bleeding. To prevent recurrence of bleeding after treatment, instruct the parents to restrict the child’s activity for 48 hours after bleeding is under control.

Advise the parents to notify the physician immediately after even a minor injury, especially to the head, neck, or abdomen.

Instruct parents to watch for signs of internal bleeding, such as severe pain and swelling in joints or muscles, stiffness, decreased joint movement, severe abdominal pain, blood in urine, tarry stools, and severe headache.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Histologic findings of acute lymphocytic leukemia

Histologic findings of acute lymphocytic leukemia

Histologic findings of acute myelogenous leukemia

Histologic findings of acute myelogenous leukemia

Peripheral blood smear in aplastic anemia

Peripheral blood smear in aplastic anemia

Normal clotting and clotting in hemophilia

Normal clotting and clotting in hemophilia