Healthcare Policy and Politics: The Risk and Rewards for Public Health Nurses

Donna M. Nickitas

Deborah Gardner

|

A comparison of the cost of treating tuberculosis patients in their homes and in hospitals is interesting and exceedingly important from an economic point of view. It costs no less than one dollar per day to care for one patient in a hospital. In most good hospitals the cost per day is from one dollar and fifty cents to two dollars and over. The sum so spent in caring for one patient for one year would be from four hundred to six hundred dollars. This sum is almost enough to supply a visiting nurse, who in one year, as has been shown, could and does visit from four to five hundred patients (Nutting, 1904, p. 501).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to

Describe the relevance of healthcare policy and politics in public health nursing.

Analyze the contextual factors that influence the development of federally funded healthcare policy.

Identify ways in which public health nurses can participate politically in healthcare reform efforts.

KEY TERMS

Advocacy

Affordable Care Act (ACA)

Economic Policy

Influence

Politics

Public Policy

Social policy

Why Care About Federal Policy?

While this question may seem rhetorical, perceptions of and experiences with the United States healthcare system can create the belief that to care about or try to understand federal policies on health care is fruitless. At least three issues contribute to this perspective. One prominent issue is the long-standing and interconnected problems the current system is unable to address: the rising costs of health care, the reduction in employer-based health care, the growing ranks of uninsured, and an inadequate supply of health providers. A second issue is that the U.S. healthcare system is a large and multipart healthcare complex that is rigidly hierarchical and not well coordinated or unified in purpose, scope, or values. And third, but interdependent with the previous issues, is that the politics and policies that shape the relationship between these inputs and outputs can seem extremely remote and hard to address. This chapter attempts to demonstrate that the linkages among these problems can be understood and that this knowledge is imperative for influencing and practicing public health nursing.

Public Health Nurses as a Political Force

Public health nurses have a professional obligation to articulate how intellectually demanding and complex public health nursing care is and to demonstrate the ways in which they have developed and implemented innovative models of care that promote health reform: expanding access, improving quality and safety, and reducing costs. Once public health nurses fully appreciate their political force, they are poised to influence healthcare policy. According to the U.S. Health Resources and Service Administration (2008), there are 3.1 million practicing nurses in the United States. As the largest segment of the healthcare workforce, nurses need to be full partners with other health professionals to achieve significant improvements at the local, national, and international levels in both the delivery and health policy arenas. As a professional partner, nurses have the expertise in care delivery, as well as the financial, technical, and political savvy to close clinical and financial gaps within a healthcare delivery system (Nickitas, 2011a). Yet, despite the large number of nurses in the workforce, they have not fully leveraged their strength to lead change, influence policy, and advance the health of the nation.

With more than three million members nationally, nurses can make a difference in policy and politics. For example, nurses have ranked high in public opinion polls, and the public believes that the endorsement by nurses for candidates for political office demonstrates a candidate’s integrity. When divided by 435 congressional districts nationally, there are approximately 5,000 registered nurses per congressional

district who can mobilize voters. The power of the “nursing numbers” has the capacity to convert votes that can make the difference in electing officials who support and endorse nursing’s core values and issues.

district who can mobilize voters. The power of the “nursing numbers” has the capacity to convert votes that can make the difference in electing officials who support and endorse nursing’s core values and issues.

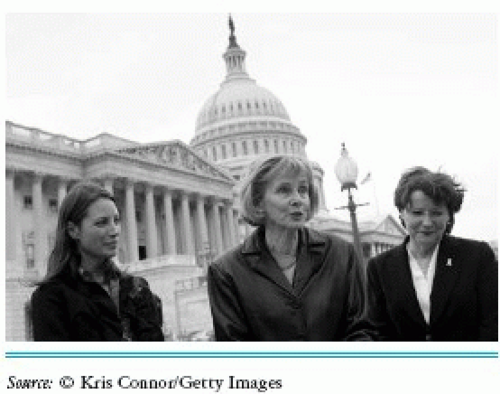

Lois Capps, Congresswoman from California uses her expertise as a school nurse in her political role. |

Nursing is the most trusted profession and has been recognized as such for the past 11 years (Gallup, 2011a). Nurses continue to outrank other professions in Gallup’s Annual Honesty and Ethics survey. Eighty-one percent of Americans say nurses have “very high” or “high” honesty and ethical standards, a significantly greater percentage than for the next-highest-rated professions, military officers and pharmacists.

Political Influence: A Call to Action

The recently released Institute of Medicine/ Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (IOM/RWJF) The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health strongly recommends that nurses become fully engaged in healthcare reform and policy by becoming involved with, speaking out about, and participating in the future of health care (IOM, 2011). Today’s public health nurses are pivotal in addressing population health, safety, and access to care. The opportunity to improve the health of communities and populations by understanding and influencing policy is a professional imperative.

Public health nurses have a responsibility to advocate for health care as a basic human right and ensure access to an affordable package of essential health services. They must use their collective political influence and become involved in the policymaking process. Influence is the ability to persuade or sway an individual or group to support or endorse a single issue (Adams, Chisari, Ditomassi, & Erickson, 2011). Adams (2009) suggests that influence is based on such factors as authority, status, knowledgebased competence, communication traits, and the use of time and timing. Learning to effectively use political influence to shape health and public policy is a key determinant in decision making, securing support and resources, as well as in motivation (Yukl & Falbe, 1990).

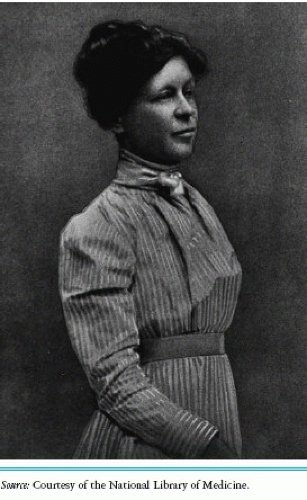

Policy issues affect all aspects of public health nursing, including promoting and protecting the health of population through health promotion and disease prevention. Public health nurses have had a distinguished history of advocacy in shaping health and public policy through the ages. For example, Lillian Wald and Lavinia Dock were early-20th century nursing leaders and activists who embraced the social issues of their day. Their professional advocacy and activism were centered in the belief that nurses were responsible for initiating and supporting action to meet the health and social needs of the public, in particular those of vulnerable populations (International Council of Nurses, 2006).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) landmark report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (2011) calls for nurses to be better prepared with requisite competencies,

including leadership and health policy, as well as competency in specific content areas including community and public health, to deliver highquality care. The commitment of public health nursing to societal well-being and access to health care cannot be overstated. Donna E. Shalala, Chair of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Initiative of the Future of Nursing at the IOM, recently stated, “…we cannot improve the quality of health care in our country without a central role for Nursing” (Nickitas, 2011b, p. 23). An example of nursing’s expanded role to increase access and provide healthcare delivery is the 2010 Affordable Care Act. It calls for an expanded role for nurses in the design of more efficient and cost-effective models of healthcare delivery (Daley, 2011). When public health nurses heed the call to political involvement in health and public policy, they not only advance the nursing profession but also improve the public’s health (Hall-Long, 2009).

including leadership and health policy, as well as competency in specific content areas including community and public health, to deliver highquality care. The commitment of public health nursing to societal well-being and access to health care cannot be overstated. Donna E. Shalala, Chair of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Initiative of the Future of Nursing at the IOM, recently stated, “…we cannot improve the quality of health care in our country without a central role for Nursing” (Nickitas, 2011b, p. 23). An example of nursing’s expanded role to increase access and provide healthcare delivery is the 2010 Affordable Care Act. It calls for an expanded role for nurses in the design of more efficient and cost-effective models of healthcare delivery (Daley, 2011). When public health nurses heed the call to political involvement in health and public policy, they not only advance the nursing profession but also improve the public’s health (Hall-Long, 2009).

Early twentieth century nursing leader, Lavinia Dock advocated woman suffrage, equating the right to vote with better healthcare outcomes. |

Public health nurses play a key role in shaping and influencing the delivery of health care. As a member of the healthcare workforce, public health nurses must understand the public policies and political forces creating the context for healthcare delivery in this country. While policy and politics may seem remote in day-to-day practice, they are the forces that drive the policies within a public health department, provide access to health resources for communities, and even decide who will breathe clean air. Resource constraints, policy, and politics are the levers continuously influencing consistency and change at all system levels. To serve your communities well, and to influence decision making that improves access, cost-effective quality, and safety, requires a basic understanding of this complex adaptive social system.

Defining Policy

The word policy is Greek in origin and is linked to citizenship (Online Dictionary of Social Sciences, n.d.). Policy represents the manifestations of ideology or belief systems about how the world should work (Rushefsky, 2008). Public policy is often used to describe government actions including, for example, economic and social policy. Economic policy promotes and regulates markets, while social policy seeks to improve the conditions of American society and achieve greater social equity (Aries, 2011).

Policy may be implemented through a variety of government systems, including the legislative, executive, or judicial branches of government.

Each of these systems has the authoritative capacity to direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of others (Block, 2008). As distinct systems, each branch of government plays a vital role in the formulation and regulation of health policy. It is important to know, in advance of influencing policy, which branch of government has the authority to legislate and regulate health care. For example, the legislative branch and executive branches of government had key roles in the formation and passage of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), and now the judicial branch is involved in the legality of the ACA as states challenge the federal mandate to make all Americans purchase healthcare coverage.

Each of these systems has the authoritative capacity to direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of others (Block, 2008). As distinct systems, each branch of government plays a vital role in the formulation and regulation of health policy. It is important to know, in advance of influencing policy, which branch of government has the authority to legislate and regulate health care. For example, the legislative branch and executive branches of government had key roles in the formation and passage of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), and now the judicial branch is involved in the legality of the ACA as states challenge the federal mandate to make all Americans purchase healthcare coverage.

Policy and Values

Policy always had a moral dimension because it relates to decisions about how to act toward others. Leavitt (2009) described this moral approach as one that involves the choices a society or organization makes to reach a desired action. These actions reflect the values and beliefs of those who develop the policies. Furthermore, policy involves how and what resources should be used to achieve those policies. Thus, policies are often expressed as goals, programs, proposals, laws, and regulations that reflect the values and beliefs of those who are developing and directing the policies (Milstead, 2013).

Policies developed by nurses have frequently shown a strong belief in the importance of assisting people to care for themselves despite their illness or disability, and this belief has distinguished nursing’s caring attribute from other professions. Caring is a value central to nursing. Watson (2008) suggests that to help the current healthcare system retain its most precious resource— competent, caring, professional nurses—a new generation of health professionals must ensure care and healing for the public, while learning about the value of serving others. If public health nurses want policies that reflect their nursing values, then they must get involved in the policy process to ensure their values are represented.

The long-standing interdependence of public policy, politics, and public health often makes it difficult to conceptualize or understand them separately. Public policy, like public health, is population-based. Policy encompasses the choices that a government makes regarding goals and priorities and the way it allocates resources to attain those goals. Public health is focused on society, seeking collectively to ensure the conditions in which people can be healthy. Public health, as a discipline, is interested in the equitable distribution of social and economic resources because they are such important influences on the health of populations (IOM, 1988). However, unlike public health, public policy reflects a broader array of competing values, beliefs, and attitudes espoused by those designing policy and the stiff competition for limited resources and immediate “felt” needs. Central to current debates are competing visions between public health and public policy. While the former field is increasingly cognizant of the need for a prevention focus, this approach

conflicts with demands within the political field because it requires taking a shared long view and investing in the future. Paralleling this tension is a broader national policy debate that pits austerity against investment as the background of policy choices. Within the theoretical framework of The Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel, federal policy development and implementation are primary components of a public health intervention used at the system level of practice impacting the health of communities (Keller, Strohschein, & Briske, 2008).

conflicts with demands within the political field because it requires taking a shared long view and investing in the future. Paralleling this tension is a broader national policy debate that pits austerity against investment as the background of policy choices. Within the theoretical framework of The Public Health Nursing Practice Intervention Wheel, federal policy development and implementation are primary components of a public health intervention used at the system level of practice impacting the health of communities (Keller, Strohschein, & Briske, 2008).

Defining Politics

Politics is often described as the process of who gets to decide what will be done and when it will be done (Milstead, 2013). It involves power and influence for key decision making and requires significant investment in social capital. Public health nurses must understand how politics drives policy decisions and have the necessary skills and competencies to care for society and the populations they serve. Kraft and Furlong (2010) suggest that politics involves how conflicts in society are identified and resolved in favor of one set of priorities or values over another. Because resources (money, time, and personnel) are limited or finite, choices must be made. For public health nurses to have the ability to advocate resources for others and effectively shape policy, they must have the necessary political skill. This requires the ability to understand another’s values and position and to use that understanding to influence others to act.

The importance of this chapter is that it will assist the reader in understanding the interface between new federal health policies that influence the public health of communities as well as public health nursing practices and the economic and political forces that are reciprocally threatening the implementation of these policies. By examining the landmark Affordable Care Act legislation, enacted by the 111th United States Congress to remedy this nation’s broken healthcare system, the challenges reformers are facing in implementing these policies will be described. The history and context that are shaping the fate of this legislation are outlined. The institutional politics at the national and state levels of government are explored. Additionally, the arguments that ushered in the new legislation, especially the critical need to control healthcare costs, connect prevention with quality care and patient safety, and to integrate technology for improving healthcare coordination will be presented. Regardless of partisan positioning, these areas provide tangible examples of issues that must be addressed in the redesign of a sustainable healthcare system that provides access to quality outcomes for all of our citizens regardless of income, race, or geographic location (Gostin, 2002).

What’s Wrong With the Current U.S. Healthcare System?

In the healthcare reform debate, much has been said or written about whether or not the healthcare reform will work, what it might

cost, and the impact it would have on each one of us as individuals. It has also been suggested from those who have great faith in our current system that it should be left alone. It may work well for some people, but on the whole our healthcare system ranks 37th out of 191 world health systems in the World Health Report 2000 (World Health Organization, 2010), and our nation has the highest rate of preventable deaths among 19 industrialized nations (Cohen, 2009). In 2010, the number of nonelderly uninsured Americans reached 49.1 million, an increase reflecting a slow economy and a decline in employer-sponsored coverage. Increases in the uninsured largely reflect adults who have lost employer-based coverage and do not qualify for public coverage. This means that despite popular images of the uninsured, the majority of uninsured are working families. Low-income workers are at the greatest risk to be uninsured because job-based coverage is often not offered; even when it is, these workers are less able to afford the premiums. The lack of health insurance affects access to health care as well as increases costs. The uninsured delay or forgo needed care, making them more likely to be hospitalized for avoidable conditions. Overall, the uninsured are less likely to receive preventive care. Cost barriers to health care have been growing in the past decade, making the uninsured more likely than the insured to be unable pay for basic necessities because of their medical bills (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011).

cost, and the impact it would have on each one of us as individuals. It has also been suggested from those who have great faith in our current system that it should be left alone. It may work well for some people, but on the whole our healthcare system ranks 37th out of 191 world health systems in the World Health Report 2000 (World Health Organization, 2010), and our nation has the highest rate of preventable deaths among 19 industrialized nations (Cohen, 2009). In 2010, the number of nonelderly uninsured Americans reached 49.1 million, an increase reflecting a slow economy and a decline in employer-sponsored coverage. Increases in the uninsured largely reflect adults who have lost employer-based coverage and do not qualify for public coverage. This means that despite popular images of the uninsured, the majority of uninsured are working families. Low-income workers are at the greatest risk to be uninsured because job-based coverage is often not offered; even when it is, these workers are less able to afford the premiums. The lack of health insurance affects access to health care as well as increases costs. The uninsured delay or forgo needed care, making them more likely to be hospitalized for avoidable conditions. Overall, the uninsured are less likely to receive preventive care. Cost barriers to health care have been growing in the past decade, making the uninsured more likely than the insured to be unable pay for basic necessities because of their medical bills (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011).

Arguably, one of the great strengths of the American healthcare system has been its strong private sector orientation, which facilitates ready access to all manner of services for those with stable coverage and strongly encourages ongoing medical innovation by product manufacturers. Our healthcare system has some of the finest medical facilities, technologies, innovations, treatments, and human talent. Many of the world’s best medical practitioners are here. Health care generates more new job opportunities than any other sector of our economy. The rapid advance of medical technology over the past 50 years has unquestionably improved the health status of millions of American citizens. Employer-sponsored insurance has played a crucial role in retaining this strong private sector presence in the U.S. health sector. However, employer-based coverage is also the Achilles’ heel of American health care. One main failing is that it is not portable or owned by the worker. Moreover, because many millions of workers must change jobs and insurance frequently, there is little incentive for prevention. As employer-based health insurance costs continue to rise, those increases are being passed on to the employee through increased insurance premiums. Finally, today’s open-ended federal tax exemption for some employer-paid premiums encourages expansive coverage, which further escalates cost (Capretta, 2009).

Despite its significant strengths, the U.S. healthcare system has long suffered from unequal access, disorganization, and waste (e.g., the value it provides does not match its enormous cost). Research conducted over many decades documents large disparities in the use of health care and in its cost from one location to another. These differences cannot be explained by contrasting rates or varying severity of illness among population groups. Furthermore, it is increasingly apparent that higher rates of healthcare use do not necessarily lead to better care; in fact, they sometimes lead to worse outcomes (Mechanic, 2011). Former White House advisor and bioethicist on health care, Ezekial Emanuel, notes that both political parties do agree that that our economy and our nation will not succeed if healthcare

costs continue to rise. The fact that few people understand how much is spent on health care versus how much needs to be spent to provide quality care, and the difference between the two undermines the importance for needing to implement healthcare reform. He points out factually, that in 2010, the United States spent $2.6 trillion on health care, averaging over $8,000 per American, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. In comparing these costs to France, which has roughly a total gross domestic product of $2.6 trillion, the United States spent on health care what the 65 million people of France spent on everything including health care. The other important problem is growth. If healthcare costs continue to grow faster than the economy (present rate of 2% a year), it will be roughly one third of the entire economy by 2035 (Emmanuel, 2011).

costs continue to rise. The fact that few people understand how much is spent on health care versus how much needs to be spent to provide quality care, and the difference between the two undermines the importance for needing to implement healthcare reform. He points out factually, that in 2010, the United States spent $2.6 trillion on health care, averaging over $8,000 per American, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. In comparing these costs to France, which has roughly a total gross domestic product of $2.6 trillion, the United States spent on health care what the 65 million people of France spent on everything including health care. The other important problem is growth. If healthcare costs continue to grow faster than the economy (present rate of 2% a year), it will be roughly one third of the entire economy by 2035 (Emmanuel, 2011).

How Does the Affordable Care Act Address Our Health System’s Problems?

On March 23, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law H.R. 3590, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148) and seven days later signed H.R. 4872, the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (P.L. 1101-152). The goals of this healthcare reform are to create a system that can provide healthcare coverage for all and no longer create personal bankruptcy. In other words, it was designed to help avoid economic disaster for employers and to hold all parties— doctors, nurses, hospitals, drug companies, and insurers—collectively responsible for making health care better, safer, and less costly (Gawande, 2009). The ACA was passed in an attempt to get policy aligned with these goals. The ACA puts in place comprehensive health insurance reforms to increase access, guarantee more healthcare choices, invest in creating a new infrastructure that holds the potential to improve care quality, and contain costs for all Americans. Indeed, the sheer scope and complexity of the nation’s healthcare system, as part of a larger political and global economic context, make the implementation of this new healthcare legislation a most formidable endeavor; this was the rationale for incremental implementation, with most changes taking place by 2014. But for the infrastructure to succeed, the tools developed by the ACA must be applied (Orszag, 2011).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree