Gastrointestinal care

Diseases

Appendicitis

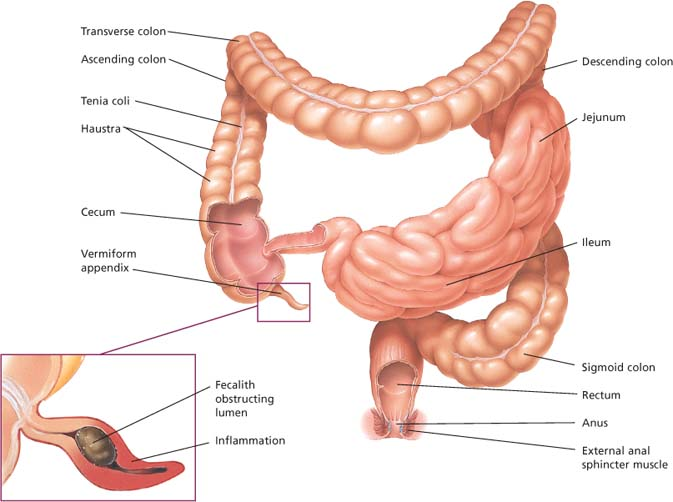

Appendicitis, the most common major surgical disease, is an inflammation of the vermiform appendix, a small, fingerlike projection attached to the cecum just below the ileocecal valve. This disorder occurs at any age, affecting both sexes equally; however, between puberty and age 25, it’s more prevalent in men. Since the advent of antibiotics, the incidence and mortality of appendicitis have declined. If untreated, this disease is fatal.

Appendicitis occurs when the appendix becomes inflamed from ulceration of the mucosa or obstruction of the lumen. It may result from an obstruction of the appendiceal lumen, caused by a fecal mass, stricture, barium ingestion, or viral infection. This obstruction sets off an inflammatory process that can lead to infection, thrombosis, necrosis, and perforation.

Signs and symptoms

Abdominal pain (initially generalized but within a few hours becomes localized in the right lower abdomen [McBurney point]; worsens on gentle percussion and when the patient coughs)

Anorexia

Nausea

Vomiting (one or two episodes)

Low-grade fever

Malaise

Constipation

Walking bent over to reduce right lower quadrant pain

Sleeping or lying supine, keeping right knee bent up to decrease pain

Normal bowel sounds

Rebound tenderness and spasm of abdominal muscles common (pain in the right lower quadrant from palpating the lower left quadrant)

Abdominal tenderness completely absent, if appendix positioned retrocecally or in the pelvis; instead, flank tenderness revealed by rectal or pelvic examination

Abdominal rigidity and tenderness that worsen as condition progresses; sudden cessation of abdominal pain signaling perforation or infarction

Eliciting abdominal pain

Eliciting abdominal painA positive response to the following tests helps diagnose appendicitis. Rebound tenderness and the iliopsoas and obturator signs can indicate such conditions as appendicitis and peritonitis.

Rebound tenderness

Help the patient into a supine position with his knees flexed to relax the abdominal muscles.

Place your hands gently on the right lower quadrant at the McBurney point (located about midway between the umbilicus and the anterior superior iliac spine).

Slowly and deeply dip your fingers into the area; then release the pressure in a quick, smooth motion.

Pain on release—rebound tenderness—is a positive sign. The pain may radiate to the umbilicus.

|

Iliopsoas sign

Help the patient into a supine position with his legs straight.

Instruct him to raise his right leg upward as you exert slight downward pressure with your hand on his right thigh.

Repeat the maneuver with the left leg.

When testing either leg, increased abdominal pain is a positive result, indicating irritation of the psoas muscle.

|

Obturator sign

Help the patient into a supine position with his right leg flexed 90 degrees at the hip and knee.

Hold the leg just above the knee and at the ankle; then rotate the leg laterally and medially.

Pain in the hypogastric region is a positive sign, indicating irritation of the obturator muscle.

|

Treatment

Appendectomy

GI intubation, parenteral fluid and electrolyte replacement, and antibiotics (for peritonitis)

Nursing considerations

Make sure the patient with suspected or known appendicitis receives nothing by mouth until surgery is

performed.

Administer I.V. fluids to prevent dehydration. Never administer cathartics or enemas because they may rupture the appendix.

Don’t administer analgesics until the diagnosis is confirmed because they mask symptoms.

Place the patient in Fowler’s position to reduce pain. (This is also helpful postoperatively.)

Never apply heat to the right lower abdomen; this can cause the appendix to rupture.

Provide preoperative care, including giving prescribed medications.

After appendectomy

Monitor vital signs and intake and output.

Give analgesics as ordered.

Administer I.V. fluids, as needed, to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance.

Document bowel sounds, passing of flatus, or bowel movements (signs of peristalsis). These signs in a patient whose nausea and boardlike abdominal rigidity have subsided indicate readiness to resume oral fluids.

Watch closely for possible surgical complications, such as an abscess or wound dehiscence.

If peritonitis occurs, nasogastric drainage may be necessary to decompress the stomach and reduce nausea and vomiting. If so, record drainage. Provide mouth and nose care.

Teaching about appendicitis

Teaching about appendicitis

Explain to the patient what happens in appendicitis.

Help the patient understand the required surgery and its possible complications. If time allows, provide preoperative teaching.

Teach the patient how to care for the incision. If he has a surgical dressing, demonstrate how to change it properly. Instruct him to observe the incision daily and to report any swelling, redness, bleeding, drainage, or warmth at the site.

Review the proper use of all prescribed medications. Make sure the patient knows how to administer each drug and understands the desired effects and possible adverse reactions.

Discuss postoperative activity limitations. Tell the patient to follow the practitioner’s orders for driving, returning to work, and resuming physical activity.

Cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, and related disorders

Cholelithiasis—the leading biliary tract disease—is the formation of stones or calculi (also called gallstones) in the gallbladder. The prognosis is usually good with treatment; however, if infection occurs, the prognosis depends on the infection’s severity and its response to antibiotics. Generally, gallbladder and duct diseases occur during middle age. Between ages 20 and 50, they’re six times more common in women, but the incidence in men and women equalizes after age 50, increasing with each succeeding decade.

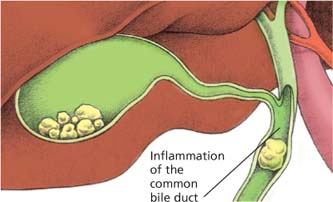

Gallstone formation can give rise to a number of related disorders, including cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and gallstone ileus. The type of disorder that develops depends on where in the gallbladder or biliary tract the calculi collect. Although the exact cause of gallstone formation is unknown, abnormal metabolism of cholesterol and bile salts clearly plays an important role.

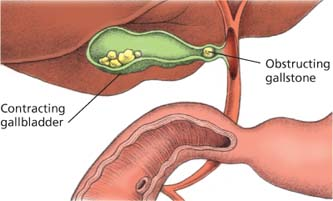

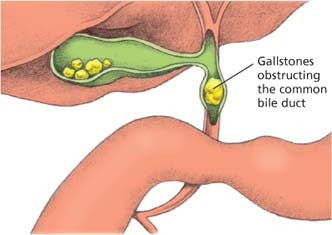

With cholecystitis, the gallbladder becomes acutely or chronically inflamed, usually because a gallstone becomes lodged in the cystic duct, causing painful gallbladder distention. In choledocholithiasis, gallstones pass out of the gallbladder and lodge in the common bile duct, causing partial or complete biliary obstruction. With cholangitis, the bile duct becomes infected; this disorder is commonly associated with choledocholithiasis and may follow percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. In gallstone ileus, a gallstone obstructs the small bowel. Typically, the gallstone travels through a fistula between the gallbladder and small bowel and lodges at the ileocecal valve.

How gallstones form

How gallstones formGallstone formation (or cholecystitis) happens when cholesterol and bile salts are abnormally metabolized. A normal liver continuously produces bile that’s concentrated and stored in the gallbladder until the duodenum needs it to help digest fat. If changes in bile composition or the gallbladder’s lining occur, gallstones form. Cholecystitis may be acute or chronic. Acute cholecystitis is usually due to partial or complete obstruction of bile flow. The figures below illustrate how gallstones form.

Liver function

Certain conditions, such as age, obesity, and estrogen imbalance, cause the liver to secrete bile that’s abnormally high in cholesterol or lacking the proper concentration of bile salts.

|

Gallstone formation

When the gallbladder concentrates this bile, inflammation may occur. Excessive reabsorption of water and bile salts makes the bile less soluble. Cholesterol, calcium, and bilirubin precipitate into gallstones.

Fat entering the duodenum causes the intestinal mucosa to secrete the hormone cholecystokinin, which stimulates the gallbladder to contract and empty. If a stone lodges in the cystic duct, the gallbladder contracts but can’t empty.

|

Gallstone obstruction

If a stone lodges in the common bile duct, the bile can’t flow into the duodenum. Bilirubin is absorbed into the blood and causes jaundice.

Biliary narrowing and swelling of the tissue around the stone can also cause irritation and inflammation of the common bile duct.

|

Signs and symptoms

Possibly no symptoms, even when X-rays reveal gallstones

Cholecystitis

Sudden onset of severe steady or aching pain in the midepigastric region or right upper abdominal quadrant

Pain that radiates to the back, between the shoulder blades or over the right shoulder blade, or just to the shoulder area (known as biliary colic)

Attack that occurs suddenly after eating a fatty meal or a large meal after fasting for an extended time

Nausea, vomiting, chills, and a low-grade fever

History of indigestion, vague abdominal discomfort, belching, and flatulence after eating high-fat foods

Jaundice

Dark-colored urine and clay-colored stools

During an acute attack, severe pain, pallor, diaphoresis, and exhaustion

Tachycardia

Gallbladder tenderness that increases on inspiration

A painless, sausagelike mass (in calculus-filled gallbladder without ductal obstruction)

Hypoactive bowel sounds (acute cholecystitis)

Cholangitis

History of choledocholithiasis and classic symptoms of biliary colic

Jaundice and pain

Spiking fever with chills

Gallstone ileus

Colicky pain that persists for several days

Nausea and vomiting

Abdominal distention

Absent bowel sounds (complete bowel obstruction)

Treatment

Surgery, including cholecystectomy (laparoscopic or abdominal), cholecystectomy with operative cholangiography, choledochostomy, or exploration of the common bile duct

Gallstone dissolution therapy in high-risk patients with small gallstones (if gallstones are radiolucent and consist all or in part of cholesterol) with oral chenodeoxycholic acid or ursodeoxycholic acid to partially or completely dissolve gallstones

Visualization and removal of calculi using a basket-shaped tool (Dormia basket) that’s inserted via percutaneous transhepatic biliary catheter under fluoroscopic guidance

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to remove calculi with a balloon or basketlike tool that’s passed through an endoscope

Lithotripsy (breaking up gallstones using ultrasonic waves); successful in those with radiolucent calculi

Low-fat diet with replacement of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K, and administration of bile salts to facilitate digestion and vitamin absorption

Nursing considerations

If the patient will be managed without invasive procedures, provide a low-fat diet and small, frequent meals to help prevent attacks of biliary colic. Also replace vitamins A, D, E, and K, and administer bile salts, as ordered.

Administer opioids and anticholinergics for pain, and antiemetics for nausea and vomiting, as ordered. Monitor for desired effects, and watch for possible adverse reactions.

If the patient vomits or has nausea, stay with him, assess his vital signs, monitor intake and output, and withhold food and fluids.

If the patient has cholangitis, give antibiotics as ordered and watch for desired effects and adverse reactions. Also monitor vital signs, and watch for signs of severe toxicity, including confusion, septicemia, and septic shock.

If surgery is scheduled, provide appropriate preoperative care, which may include insertion of a nasogastric (NG) tube.

After surgery

After percutaneous transhepatic biliary catheterization or ERCP to remove gallstones, assess vital signs. Allow the patient nothing by mouth until the gag reflex returns. Monitor intake and output, keeping in mind that urine retention can be a problem. Observe the patient for complications, including cholangitis and pancreatitis.

Be alert for signs of bleeding, infection, or atelectasis. Evaluate the incision site for bleeding. Serosanguineous and bile drainage is common during the first 24 to 48 hours if the patient has a wound drain, such as a Jackson-Pratt or Penrose drain. If, after a choledochostomy, a T tube drain is placed in the duct and attached to a drainage bag, make sure the drainage tube has no kinks. Also make sure the connecting tubing from the T tube is well secured to the patient to prevent dislodgment. Measure and record drainage daily (200 to 300 ml is normal).

If the patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, assess for “free-air” pain caused by carbon dioxide insufflation. Encourage ambulation soon after the procedure to promote gas absorption.

Monitor intake and output. Provide appropriate I.V. fluid intake. Allow the patient nothing by mouth for 24 to 48 hours or until bowel sounds resume and nausea and vomiting cease (postoperative nausea may indicate a full urinary bladder). Administer antiemetics, as ordered, for nausea and vomiting. Monitor NG tube drainage for color, amount, and consistency.

When peristalsis resumes, remove the NG tube and begin a clear liquid diet, advancing diet as tolerated. If the patient doesn’t void within 8 hours (or if he voids an inadequate amount based on I.V. fluid intake), percuss over the symphysis pubis for bladder distention (especially in patients receiving anticholinergics). Avoid catheterization, if possible.

Encourage leg exercises every hour. The patient should ambulate the evening after surgery. Encourage hourly coughing and deep breathing. Discourage sitting in a chair. Provide antiembolism stockings to support leg muscles and promote venous blood flow, thus preventing stasis and possible clot formation. Have the patient rest in semi-Fowler’s position as much as possible to direct any abdominal drainage into the pelvic cavity rather than allowing it to accumulate under the diaphragm.

Teaching about cholecystitis

Teaching about cholecystitis

Teach the patient about cholecystitis and the reasons for his symptoms.

Explain scheduled diagnostic tests, reviewing pretest instructions and necessary aftercare.

If a low-fat diet is prescribed, suggest ways to implement it and how the changes help to prevent biliary colic. If necessary, ask the dietitian to reinforce your instructions.

Review the proper use of prescribed medications, explaining their desired effects. Point out possible adverse effects, especially those that warrant a call to the practitioner.

Reinforce the practitioner’s explanation of the ordered treatment, such as surgery, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, or lithotripsy. Make sure the patient

fully understands the possible complications, if any, associated with his treatment.

Before and after surgery

Before surgery, teach the patient to breathe deeply, cough, expectorate, and perform leg exercises that are necessary after surgery. Also teach splinting, repositioning, and ambulation techniques.

Explain the procedures that will be performed before, during, and after surgery to help ease the patient’s anxiety and ensure his cooperation. Teach the patient who will be discharged with a T tube how to empty it, change the dressing, and provide skin care.

On discharge (usually 4 to 7 days after traditional surgery), advise the patient against heavy lifting or straining for 6 weeks. Urge him to walk daily. Tell him that food restrictions are unnecessary unless he has intolerance to a specific food or some underlying condition (diabetes, atherosclerosis, or obesity) that requires such restriction.

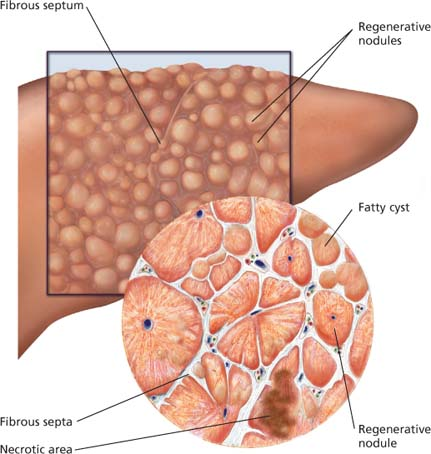

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is a chronic hepatic disease characterized by diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells. As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, this disease alters liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency. Obstruction to venous flow leads to portal hypertension, ascites, esophageal varices, and gastric varices. As the liver becomes cirrhotic, it can no longer change ammonia (waste product of protein metabolism) to urea so that it can be eliminated by the kidney. Elevated ammonia levels in the blood are thought to contribute to hepatic encephalopathy.

Most cases are a result of alcoholism, but toxins, biliary destruction, hepatitis, and a number of metabolic conditions may stimulate the destruction process. There are many types of cirrhosis; causes differ with each type and include:

Laënnec’s cirrhosis—also called portal, nutritional, or alcoholic cirrhosis—is the most common type.

Cirrhosis is characterized by irreversible chronic injury of the liver, extensive fibrosis, and nodular tissue growth. These changes result from:

liver cell death (hepatocyte necrosis)

collapse of the liver’s purporting structure (the reticulin network)

distortion of the vascular bed (blood vessels throughout the liver)

nodular regeneration of the remaining liver tissue.

Signs and symptoms

Abdominal pain

Diarrhea

Fatigue

Nausea and vomiting

Chronic dyspepsia

Constipation

Pruritus

Weight loss

Tendency for frequent nosebleeds, easy bruising, and bleeding gums

Changes in level of consciousness

Telangiectasis on the cheeks; spider angiomas on the face, neck, arms, and trunk; gynecomastia; umbilical hernia; distended, abdominal blood vessels; ascites; testicular atrophy; palmar erythema; clubbed fingers; thigh and leg edema; ecchymosis; and jaundice

Large, firm liver with a sharp edge (early phase)

Decreased liver size and nodular edge due to scar tissue (late phase)

Enlarged spleen

Treatment

Vitamins and nutritional supplements to promote healing of damaged hepatic cells and improve nutritional status

Restricted sodium consumption (500 mg/day)

Limited liquid intake (1,500 ml/day) to help manage ascites and edema

Antacids and histamine antagonists to reduce gastric distress and decrease the potential for GI bleeding

Potassium-sparing diuretics, such as furosemide (Lasix), to reduce ascites and edema

Vasopressin for esophageal varices

Rifaximin to treat acute hepatic encephalopathy

Lactulose to reduce a high ammonia level

Paracentesis to relieve abdominal pressure (for ascites)

Peritoneovenous shunt to divert ascites into venous circulation

Gastric intubation and esophageal balloon tamponade to control bleeding from esophageal varices or other GI hemorrhage

Esophageal balloon tamponade to compress and stop bleeding from esophageal varices

Sclerotherapy for repeated hemorrhagic episodes despite conservative treatment

Blood transfusions for massive hemorrhage; crystalloid or colloid volume expanders given to maintain blood pressure

Nursing considerations

Monitor vital signs, intake and output, and electrolyte levels to determine fluid volume status.

To assess fluid retention, measure and record abdominal girth every shift. Weigh the patient daily and document his weight.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Appendix obstruction and inflammation

Appendix obstruction and inflammation

Cirrhotic changes

Cirrhotic changes