Gastritis

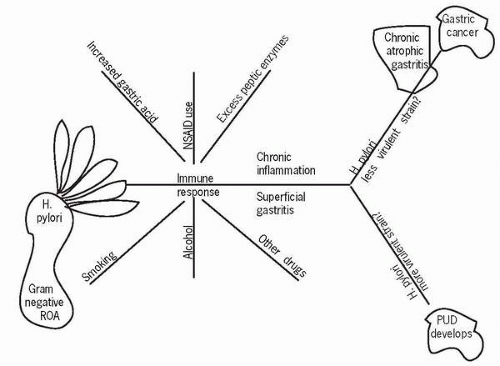

Gastritis is a documented inflammation of the gastric mucosa. It has many causes, can occur as either an acute or chronic problem, or can be related to a specific condition of which it is a symptom.

Pathophysiology

Chronic gastritis is defined as the presence of chronic mucosal inflammatory changes of the superficial and glandular portions of the gastric mucosa that, if left untreated, lead to the development of mucosal atrophy

and epithelial metaplasia. Typical inflammatory changes include lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate in the lamina propria and inflammation of mucosal pits. There are also loss of glands and mucosal atrophy.

and epithelial metaplasia. Typical inflammatory changes include lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate in the lamina propria and inflammation of mucosal pits. There are also loss of glands and mucosal atrophy.

The two types of chronic gastritis are type A (fundal), which is autoimmune and associated with pernicious anemia, and type B (antral), which is more common and caused by Helicobacter pylori. Chronic gastritis can also be a combination of both types A and B with persistent presence of lymphocytes and plasma cell involvement. Type A has positive antibodies to parietal cells, and approximately 20% of those afflicted are 60 years of age or older. Other populations affected by type A are those with Addison’s disease or vitiligo. Approximately half of those with type A test positive for thyroid antibodies.

Type B is more common. The increased inflammation is directly correlated with the level of causative organisms found. Pan-gastritis develops over a period of 15-20 years and increases with age. Most patients improve with treatment. Only about 15% of those infected with the organism actually develop gastritis. In some areas of the world it is almost endemic. For example, it has been found in almost 80% of Puerto Ricans; however, most remain asymptomatic all their lives.

The early phase of chronic gastritis is a superficial gastritis that is limited to the lamina propria. Atrophic gastritis is an inflammation that extends deeper into the mucosal layer with progressive destruction of cells. Gastric atrophy occurs as a result of the loss of glandular structures when the mucosa is thinned, as seen by endoscopy with visualization of the blood vessels.

The most common pathogen responsible for gastritis in Western countries is the gram-negative rod H. pylori. This organism can be transmitted by a number of routes. As it has been identified in dental plaque, an oral route is one mode thought to occur by kissing or sharing utensils, food, or drink. The gastric-oral route occurs via vomitus and the fecal-oral route via poor hand-washing techniques. It is believed to be transmitted in childhood and remains dormant until later in life when an unknown factor causes it to become active.

When activated, H. pylori begins as an acute infection, with nausea and/or vomiting and abdominal pain that appears to resolve in a few days. The organism does not disappear, however, but rather remains and produces an enzyme called urease that decomposes the byproduct

of protein metabolism, urea, to produce ammonia. Ammonia neutralizes gastric acid, allowing the organism to thrive. It colonizes areas safely tucked beneath the gastric mucosa adjacent to the gastric epithelial cells, producing an inflammatory response. Some organisms burrow deeper into the gastric glands, causing the glands to atrophy. It is thought that chronic gastritis is a result of the ammonia and other byproducts of the organism damaging the mucosal surface. Most people infected with H. pylori are asymptomatic, but the infection is strongly associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease. Those infected are at risk for adenocarcinoma and low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma due to the chronic T-cell stimulation caused by the organism that increases cytokinin production. Increased cytokinin promotes B-cell tumor formation, leading to lymphoma. With treatment of H. pylori, there is noted tumor regression.

of protein metabolism, urea, to produce ammonia. Ammonia neutralizes gastric acid, allowing the organism to thrive. It colonizes areas safely tucked beneath the gastric mucosa adjacent to the gastric epithelial cells, producing an inflammatory response. Some organisms burrow deeper into the gastric glands, causing the glands to atrophy. It is thought that chronic gastritis is a result of the ammonia and other byproducts of the organism damaging the mucosal surface. Most people infected with H. pylori are asymptomatic, but the infection is strongly associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease. Those infected are at risk for adenocarcinoma and low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma due to the chronic T-cell stimulation caused by the organism that increases cytokinin production. Increased cytokinin promotes B-cell tumor formation, leading to lymphoma. With treatment of H. pylori, there is noted tumor regression.

Most people infected with H. pylori are asymptomatic, but the infection is strongly associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease.

Most people infected with H. pylori are asymptomatic, but the infection is strongly associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access