Evidence-Based Practice

Carol M. Baldwin

Alyce A. Schultz

Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk

Jo Rycroft-Malone

Nurse Healer OBJECTIVES

|

Theoretical

Explore the concept of evidence-based practice (EBP).

Review the historical underpinnings of EBP.

Compare and discriminate between individual and system-wide models of EBP.

Discuss ways in which EBP has redirected priorities for evaluating best practices in nursing research.

Compare and contrast the barriers to and strengths of evidence-based care.

Examine international approaches to EBP in holistic nursing practice

Clinical

Describe the five steps to searching for the best evidence.

Apply the EBP process to a peer-reviewed journal article and assess the evidence for making a decision or practice change.

Identify resources that can be used to incorporate EBP in your clinical setting.

Discuss ways in which EBP can be adapted at your clinical setting to enhance best practices in the holistic caring process.

Practice framing a clinical issue of interest into a standardized clinical question, such as the PICOT format in your clinical setting.

Define and describe ways in which EBP informs comparative effectiveness research.

Personal

Set aside time to learn more about how EBP can enhance the holistic caring process.

Attend an EBP conference or workshop.

Develop expertise in EBP through an online course or program of study.

Search online resources to appreciate the application of EBP in clinical practice nationally and internationally.

DEFINITIONS

Comparative effectiveness research (CER): The conduct and synthesis of research that compares the benefits and harms of various interventions and strategies for preventing, diagnosing, treating, and monitoring health conditions in real-world settings. The purpose of this research is to improve health outcomes by developing and disseminating evidence-based information to patients, clinicians, and other decision makers about which interventions are most effective for which patients under specific circumstances.

Evidence-based practice (EBP): The conscientious use of the best available evidence combined with the clinician’s expertise and judgment and the patient’s preferences and values to arrive at the best decision that leads to high-quality outcomes.

PICOT: A standardized format for asking the searchable, answerable question: population of interest (P); the intervention or

issue of interest (I); the comparison intervention, if relevant (C); the outcome (O); and time frame (T), if relevant.

issue of interest (I); the comparison intervention, if relevant (C); the outcome (O); and time frame (T), if relevant.

▪ HOLISTIC NURSING AND EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

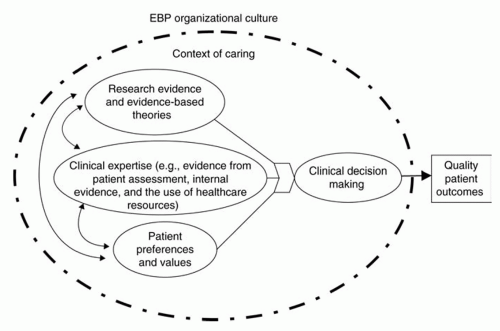

The science and art of holistic nursing honor an individual’s subjective experience about health, health beliefs, and values and develop therapeutic partnerships with individuals, families, and communities that are grounded in nursing knowledge, theories, research expertise, intuition, and creativity.1 Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the conscientious use of the best available evidence combined with the clinician’s expertise and judgment and the patient’s preferences and values to arrive at the best decision that leads to high-quality outcomes.2,3 Research has shown that when these conceptual components of EBP are integrated within a context of caring (Figure 35-1), components that are consonant with the science and art of holistic nursing, they lead to the best clinical decision making, as well as best outcomes for patients, families, communities, and populations.4

▪ HISTORICAL UNDERPINNINGS OF CURRENT EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Knowledge translation or the use of research evidence to improve clinical outcomes is not a 21st-century phenomenon. Neither is the difficulty with or resistance to the application of new scientific knowledge to practice. For example, the usefulness of citrus juice for the treatment of scurvy was noted in the 16th century, although it would be another 100 years for these findings to be put into practice by the British Admiralty.5 Another example is that of the work of Ignatz Semmelweis, who recognized that obstetricians were carrying the contagion for puerperal fever from the morgue to the delivery room.5 His recommendation to reduce maternal mortality by hand-washing was rejected by the Viennese medical society in the mid-18th century with a mantra used today that contradicts evidence to practice, “Because we’ve always done it that way.”

As the disease transmission theory was being rejected by practicing physicians, Florence Nightingale, as a nurse in the Crimean War

(1853-1856), found that washing hands between patients along with other public health measures reduced morbidity and mortality among the soldiers.6 Recognized as the first nurse to conduct and use research, Nightingale showed that the quality of care can be improved through sanitary conditions, careful data collection, and critical thinking.7 More than 150 years later, Nightingale’s insight into the need for research laid the groundwork for evidence-based practice in holistic nursing when she wrote:

(1853-1856), found that washing hands between patients along with other public health measures reduced morbidity and mortality among the soldiers.6 Recognized as the first nurse to conduct and use research, Nightingale showed that the quality of care can be improved through sanitary conditions, careful data collection, and critical thinking.7 More than 150 years later, Nightingale’s insight into the need for research laid the groundwork for evidence-based practice in holistic nursing when she wrote:

In dwelling upon the vital importance of sound observation, it must never be lost sight of what observation is for. It is not for the sake of piling up miscellaneous information or curious facts, but for the sake of saving life and increasing health and comfort.8

▪ NURSING RESEARCH INTO EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

For 75 years, research has been recognized as important for improving nursing education and practice. Sigma Theta Tau International (STTI), the only nursing honor society, offered the first nursing research grant in 1936. Thirty-five years later, research became a required course in baccalaureate nursing programs. As research skills and knowledge became a requirement for the professional nurse, concern for use of research findings in practice and strategies to increase research utilization became a top priority. In the mid-1970s, federal grants supported the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education (WICHE) Regional Program for Nursing Research Development, the Conduct and Utilization of Research in Nursing (CURN), and Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training (NCAST).9 The Regional Program for Nursing Research Development was conducted in the 13 western states to teach practicing nurses how to identify researchable practice issues, critique the current research literature, initiate and lead practice changes, and evaluate their outcomes.10 The CURN project was designed to develop practice protocols based on the synthesis of the best available science. Ten research-based protocols were completed and evaluated for their applicability.11 NCAST, based on the early findings of Dr. Kathryn Barnard, focused on teaching cues to maternal-child interaction to nurses in Washington using the new satellite system. Stetler and Marram, as young doctoral students, published the original version of their research utilization model for use by advanced practice nurses as leaders and mentors for changing clinical nursing practice.12 An early meta-analysis showed that patients who received research-based interventions experienced outcomes that were 28% better than patients receiving routine care.13 These findings strongly supported the efforts to increase the use of research by direct care providers.

Despite this foundation of nursing knowledge built on practice based on evidence, Ketefian concluded that nurses who conducted research and nurses who practiced at the bedsides lived in separate “subcultures” and that to narrow this gap, researchers must publish research findings in a format that practicing nurses could read and use.14 It was apparent that even though individual nurses learned and supported the concepts of research utilization, there were many barriers to actually implementing and maintaining research-based practice changes.15,16,17

Further studies exploring barriers to and facilitators of research use were conducted in the 1980s, the 1990s, and continue today.9,18 Funk and colleagues, using the concepts within Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation model, explored the individual and the organizational challenges to the use of research in the early 1990s. They reported barriers associated with the characteristics of the adopter, the organization, the innovation itself, and the communication and dissemination of the findings. These findings encouraged the development of models and programs addressing organizational and dissemination barriers. Using the Dissemination Model, Funk et al. held a series of national conferences on use of research in practice.19 Cronenwett implemented research utilization conferences at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Hospitals that focused on integrative reviews for promoting research use by direct care nurses.20 An early model for addressing organizational challenges was implemented in a rural Iowa hospital that was later adapted at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics.21 Four educational videos on research utilization for direct care nurses were developed to support the Organizational Process Research

Utilization Model.22,23,24,25 Titler and colleagues expanded on this organizational model in their development of the Iowa Model for Research in Practice.26 Rutledge and Donaldson received federal funding to develop and implement the Orange County Research Utilization in Nursing (OCRUN) project, focusing on building organizational capacity as a tool for increasing research utilization.27

Utilization Model.22,23,24,25 Titler and colleagues expanded on this organizational model in their development of the Iowa Model for Research in Practice.26 Rutledge and Donaldson received federal funding to develop and implement the Orange County Research Utilization in Nursing (OCRUN) project, focusing on building organizational capacity as a tool for increasing research utilization.27

As it became evident that much of nursing care was based on best practice and the methodology for and emphasis on quality improvement was increasing, more forms of evidence began to be used as the basis for practice. In the early 1990s, Sackett and colleagues coined the term evidencebased medicine to add credibility to internal quality improvement data and common practices that were providing good patient outcomes.28 Evidence-based practice soon became the term used to describe practices by all healthcare professionals. One of the early interdisciplinary models for evidence-based practice was developed at the University of Colorado to provide the framework for quality improvement activities.29 From the mid-1990s to the present, a number of new quality improvement and evidence-based practice models and frameworks have been developed.

▪ CONCEPTUAL MODELS FOR EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

From these early underpinnings, a variety of conceptual models has emerged for EBP, including models that focus on the EBP process for individual clinicians, such as the model of DiCenso and colleagues,30 the Stetler Model,31 and the Clinical Scholar Model.32 Several models focus on system-wide implementation of EBP, including the Iowa Model,33 the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) Model,34 and the Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model.4 Although these models are useful in conceptually guiding the implementation of EBP for individuals and within systems, there is a pressing need for further testing to support them empirically. Exemplars for the individual system-wide models are described in this chapter.

Exemplar: The DiCenso Model

The DiCenso Model of EBP,30 adapted from Haynes,35 promotes the use of research findings within the context of an evidence-based decision-making framework.4 The individual clinician integrates the best research evidence with the patient’s clinical status, preferences, action, and circumstances; available healthcare resources; and clinical expertise to decide on the interventions or type of care to be delivered. Aspects of this approach are described using a clinical scenario and an exemplar analysis when the principles of the EBP process are used to critically appraise an article from the Journal of Holistic Nursing later in this chapter.

Exemplar: The Clinical Scholar Model and Program

Clinical scholars are agents of change whether through promoting the spirit of inquiry in the areas where they work, translating new knowledge into practice using internal and external evidence, or generating new knowledge through the conduct of research. The Clinical Scholar Model and Program provides a framework and process for these agents of change.

Seeds for the Clinical Scholar Model were sown in 1980 when Dr. Janelle Krueger in her keynote address at one of the first national nursing research conferences, Promoting Nursing Research as a Staff Nursing Function, emphasized that staff nurses could “use” and “do” research.10 She argued that research utilization and conduct should be an expectation of bedside nurses because they are the link between research and practice and can identify problems that need to be researched. During the 1990s, staff nurses at Maine Medical Center in Portland with the mentorship of a doctorally prepared nurse researcher learned how to apply research findings to practice and answer their own burning clinical questions by conducting their own studies. The Clinical Scholar Program was developed to facilitate larger cohorts of professional nurses who were interested in improving quality of care through the use of internal and external evidence.

The Clinical Scholar Model is inductive, decentralized, and predicated on “building a

community” of clinical scholars to serve as mentors anywhere patient care is provided.32 The clinical scholar is always questioning whether a procedure needs to be performed at all and, if so, whether there is a more efficient and effective way of providing the same care. Clinical scholarship, as described in a Sigma Theta Tau International position paper,36 is an intellectual process, steeped in curiosity that challenges traditional nursing practice through observation, analysis, synthesis, application, and dissemination, concepts that form the structure of the Clinical Scholar Model.32,37 Qualitative and quantitative studies are reviewed for applicability to practice and knowledge generation research designs are based on the clinical inquiry.

community” of clinical scholars to serve as mentors anywhere patient care is provided.32 The clinical scholar is always questioning whether a procedure needs to be performed at all and, if so, whether there is a more efficient and effective way of providing the same care. Clinical scholarship, as described in a Sigma Theta Tau International position paper,36 is an intellectual process, steeped in curiosity that challenges traditional nursing practice through observation, analysis, synthesis, application, and dissemination, concepts that form the structure of the Clinical Scholar Model.32,37 Qualitative and quantitative studies are reviewed for applicability to practice and knowledge generation research designs are based on the clinical inquiry.

The Clinical Scholar Program, based on the Clinical Scholar Model, is a series of six interdisciplinary all-day workshops, generally presented one month apart. The goals of the program are to: (1) promote a culture of EBP and clinical scholarship through a program of interdisciplinary clinical research and EBP at the bedside, extending work that has already been initiated in a clinical setting; and (2) prepare a cadre of direct care providers as clinical scholars to implement change and evaluate practice based on evidence. The clinical scholars serve as mentors/champions to other staff.

The Clinical Scholar Model serves as the framework for several academic and community healthcare facilities across the country including Scottsdale Healthcare System; John C. Lincoln North Mountain Hospital; St. Joseph’s Hospital in Marshfield, Wisconsin; Maine Medical Center; St. Joseph Medical Center in Kansas City, Missouri; the James Comprehensive Cancer Center at The Ohio State University; Banner Del E. Webb Medical Center; and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.38,39,40 Concepts of the Clinical Scholar Model have been adapted into models within nursing departments at Baylor Health Care System and Mayo Clinic and also serve as the underlying framework for the Maine Nursing Practice Consortium in northern Maine and the Texas Christian University Evidence-Based Practice and Research (EBPR) Collaborative among urban hospitals in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.41,42

Exemplar: Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) Model

If implementation was straightforward, the production and dissemination of evidence in the form of guidelines, followed by an education or teaching package, would lead to an expectation that practitioners would automatically integrate them into their everyday practice. Politically and educationally, there has been a focus on developing the skills and knowledge of individual practitioners to appraise research and make rational decisions. As such, the emphasis has been placed on developing the skills of individual nurses to be able to find and critically appraise research evidence in the hope that this will influence its use in practice.

Despite these efforts and considerable investment, for the most part, research evidence is still not used routinely in practice. Over recent years, there has been a shift to recognize that, in fact, the process of implementing evidence into practice is more complex than some rational or linear models and approaches to implementation imply. The individual nurse cannot be isolated from all the bureaucratic, political, organizational, and social factors that affect change.43,44,45,46,47 The implementation of research-based practice depends on an ability to achieve significant and planned behavior change involving individuals, teams, and organizations.48

Stetler and colleagues conducted a study in which the importance of organizational context in the routine use of EBP was highlighted.47,49 Their research shows that some key contextual features enable the institutionalization of EBP. These features include leadership in EBP at all levels of the organization from chief nursing officer to staff nurse, a supportive organizational culture, effective multidisciplinary team work, and coherent policies and procedures. This research supports the idea that although it is critical to have reflective and inquiring nurses, their ability to practice in an evidence-based way may be more or less facilitated by the context in which they work.

The PARIHS framework was developed to represent the complexities involved in implementing evidence into practice.19,34 The successful

implementation (SI) of evidence into practice is a function (f) of the nature and type of evidence (E), the qualities of the context (C) in which the evidence is to be implemented, and the way the process is facilitated (F); therefore, SI = f (E,C, F). It provides a practical and conceptual heuristic to guide implementation and practice improvement activity, which takes multiple factors into account and acknowledges the dynamism in implementation processes. This conceptual and theoretical framework has been used for research and evaluation, the basis for tool development, modeling research utilization, and evaluating the facilitation of interventions.34

implementation (SI) of evidence into practice is a function (f) of the nature and type of evidence (E), the qualities of the context (C) in which the evidence is to be implemented, and the way the process is facilitated (F); therefore, SI = f (E,C, F). It provides a practical and conceptual heuristic to guide implementation and practice improvement activity, which takes multiple factors into account and acknowledges the dynamism in implementation processes. This conceptual and theoretical framework has been used for research and evaluation, the basis for tool development, modeling research utilization, and evaluating the facilitation of interventions.34

Exemplar: Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model for System-wide Implementation and Sustainability of EBP

In 1999, Bernadette Melnyk conceptualized the ARCC Model as part of a research strategic planning initiative involving faculty from a school of nursing and school of medicine. The purpose was to launch an initiative that would closely integrate clinical practice and research to advance EBP within an academic medical center and healthcare community.50,51 The ARCC Model has expanded to include multiple strategies for advancing EBP within healthcare organizations. The key element for implementing and sustaining system-wide EBP in the model is a cadre of EBP mentors who facilitate clinician and organizational culture change to EBP.4 The ARCC Model has been implemented in several healthcare systems and agencies, including the Visiting Nurse Service of New York, Pace University, SUNY Upstate Medical Center, the University of Rochester, the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and Washington Hospital Healthcare System.4 These liaisons have fostered empirical testing of the model, and findings from studies support multiple aspects of the ARCC Model at the preceding institutions.50,51

Within the conceptual framework of the ARCC Model (see Figure 35-1), the first step to system-wide implementation is the assessment of an organization’s strengths and limitations in advancing EBP. Once strengths and limitations are identified, a key implementation strategy in the ARCC Model, the development of a cadre of EBP mentors, is initiated. The EBP mentor is typically an advanced practice nurse with in-depth EBP knowledge and skills. The mentor possesses individual behavior and organizational change skills, provides mentorship, and facilitates improvement in clinical care and patient outcomes through EBP implementation, quality improvement, and outcomes management projects. Goals of the ARCC Model include (1) promoting EBP among both advanced practice and staff nurses as well as transdisciplinary clinicians, (2) establishing a cadre of EBP mentors to facilitate system-wide implementation of EBP in healthcare organizations, (3) disseminating and facilitating use of the best evidence from well-designed studies to advance an evidencebased approach to clinical care, (4) designing and conducting studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the ARCC Model on the process and outcomes of clinical care, and (5) conducting studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the EBP implementation strategies.3,50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access