Environmental Health

Susan Luck

Lynn Keegan

Nurse Healer OBJECTIVES

|

Theoretical

Identify three principles that can direct human endeavors toward a sustainable future.

Describe three characteristics of a sustainable community.

Describe four ways in which substantive systems changes can diminish toxic exposures in life.

Clinical

Examine environmental hazards, and make a commitment to reducing these hazards in your home, community, and workplace.

Examine systems changes that can reduce toxic exposures in the hospital or healthcare environment where you work.

Subscribe or arrange to have consistent access to periodical literature specific to clinical application of environmental principles (e.g., Health Care Without Harm Newsletter, Physicians for Social Responsibility) and website information (Environmental Working Group,www.ewg.org).

Identify and act on ways to influence environmental accountability in the workplace.

Commit to joining an organization created to influence the direction of future sustainability in health care.

Become sensitive to the environmental space in the institution, health agency, or clinic.

Explore with other staff possibilities for creating healing environments in the workplace.

Personal

Increase knowledge of the relationship between health and the environment.

Assess the health of your personal environment.

Increase awareness on how to reduce your environmental imprint (i.e., recycling).

Volunteer and join local groups and organizations to support environmental efforts in your community.

Explore what is essential about environmental relationships in your life.

Eliminate unhealthy exposures in your personal environment (e.g., stale air, artificial lighting, subliminal noises, chemicals) whenever possible.

Experiment with healing colors, scents, textures, sound, and lighting in your personal environment.

DEFINITIONS

Ambience: An environment or its distinct atmosphere; the totality of feeling that one experiences from a particular environment.

Anthropocentrism: The worldview that places human beings as the central fact or final aim of the universe.

Bisphenol A (BPA): An organic compound with two phenol functional groups. It is used to make polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resins, along with other applications, and since the mid-1930s is known to be estrogenic.

Chaos Theory: Sometimes called the “new science,” this theory offers a way of seeing order and patterns where formerly only the random, the erratic, and the unpredictable had been observed.

Detoxification: The metabolic process by which the toxic qualities of a poison or toxin are reduced or eliminated from the body.

Earth jurisprudence: Earth law recognizes the Earth as the primary source of law that sets human law in a context that is wider than humanity

Ecology: The scientific study of interrelationships between and among organisms, and among them and all aspects, living and nonliving, of their environment.

Ecominnea: The concept of an ecologically sound society.

Electromagnetic fields (EMFs): The field force in motion coupled with electric and magnetic fields that are generated by time-varying currents and accelerated charges.

Endocrine disruptors (xenoestrogens): Synthetic hormone-mimicking compounds found in many pesticides, drugs, plastics, and personal care products.

Environment: Everything that surrounds an individual or group of people: physical, social, psychological, cultural, or spiritual characteristics; external and internal features; animate and inanimate objects; climate; seen and unseen vibrations, frequencies, and energy patterns not yet understood.

Environmental ethics: A division of philosophy concerned with valuing the environment, primarily as it relates to humankind, secondarily as it relates to other creatures and to the land.

Environmental justice: A subbranch of ethics examining the innate and relational value among organisms and all aspects of their environment.

Epistemology: The branch of philosophy that addresses the origin, nature, methods, and limits of knowledge.

Ergonomics: The study of and realization of the importance of human factors in engineering.

Permaculture: An approach to designing human settlements and agricultural systems that are modeled on the relationships found in natural ecologies.

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs): Chemical substances that persist in the environment, bioaccumulate through the food web, and pose a risk of causing adverse effects to human health and the environment.

Personal space: The area around an individual that should be under the control of that individual, including air, light, temperature, sound, scent, and color.

Phthalates: Classified as “plasticizers,” a group of industrial chemicals used to make plastics such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) more flexible or resilient. They are also known to be endocrine disruptors.

Precautionary principle: When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures shall be taken, even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.

Restorative justice: An ethical perception that directs that environmental damages not only be curtailed, but also repaired and recompensed in some meaningful way.

Superfund sites: Hazardous waste landfills or abandoned manufacturing sites, names of which appear on the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Priorities List.

Sustainable future: Meeting the needs of the present without compromising the needs of future generations.

Toxic substance: A substance that can cause harm to a person through either short- or long-term exposure, as by (1) inhalation;

(2) ingestion into the body in the form of vapors, gases, fumes, dusts, solids, liquids, or mists; or (3) skin absorption.

(2) ingestion into the body in the form of vapors, gases, fumes, dusts, solids, liquids, or mists; or (3) skin absorption.

▪ THEORY AND RESEARCH

To engage successfully with life in modern times, we are challenged to increase awareness of how our external environment affects our health and the health of our clients/patients, families, communities, and the planet. In the spirit of Florence Nightingale, as healthcare providers and holistic nurses, how can we develop self-awareness and self-care practices that support our own inner and external healing environments? How can we integrate environmental assessment tools, education, and strategies into our professional practice and commit ourselves as Earth dwellers and Earth citizens, to the following:

Recognize that we are the microcosm of the macrocosm; a world of vast complexity and unpredictability; understanding that our health and the health of our planet are inextricably interwoven.

Engage in practices that create healing environments in our home, workplace, and community.

Take the risk to challenge the existing structures and maintain values and convictions to create healthier environments.

Reside in knowing that each individual makes a difference toward healing the global community beginning with individual actions.

Experience the fullness of life and the wonders of the natural world.

Environmental Leadership in Holistic Nursing

In its broadest sense, the term environment can mean everything, both within and external to each person. As a result, it is a challenge to determine for ourselves and others what constitutes a healing environment. In defining the constellation of environment in a grand way, five themes can be used to form a constellation—a mental map—to conceptualize the environmental world and the human place in it: (1) sharing, listening, and learning through our personal and collective life stories; (2) increasing self-awareness and self-care when living in a toxic world; (3) choosing a sustainable future; (4) building communities that support learning and positive actions for creating change: start local, think global; and (5) working from the inside out: healing our internal and external environments.

Telling Our Story: Local to Global

Each nurse, and each client, has a unique and personal story to tell. Everyone has an explanatory narrative that encompasses the multidimensional layers of being human. Listening to our own story and the story of others reveals the storyteller’s beliefs and worldview and opens doors to exploring and expanding possibilities for growth and change in our movement toward wholeness. Within our holistic nursing worldview, we embrace the interconnectedness of body, mind, and spirit, knowing that when there is disharmony or disruption in our internal or external environment, we are out of balance. As living beings, we are a reflection of our world, and any environmental assault directly affects our energetic patterns and well-being.

When considering the environment, it is imperative to listen and respond to a larger story, not only as practitioners, but also as members of humankind. This reaffirms what we deeply know through all the senses as we ask ourselves, “What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be an Earth citizen? What are our beliefs about health when we tell our story? Do we consider all of the possible influences that affect our daily lives, and those with whom we live and work? How can we face the great ecological crises of our time (as recently witnessed and experienced in Japan)? How does each of our stories contribute to the larger story? How does changing our own story lead to planetary change?” When we embrace the matrix of our own being, we can understand, respond to, and participate in positive actions, raising the level of consciousness of our oneness with the universe. Richard Tarnas, a philosopher and historian of Western thought, helped bring this existential human predicament into consciousness.1

There are two versions of the evolution of human consciousness. Both are basic truths and deep patterns in the psyche that inform an individual’s day-to-day experience in various ways. One is progress and heroic advance, characterized by gradual, progressive, and familiar

milestones of discovery and accomplishment: the harnessing of electricity and nuclear fission, for example. Generally, this equates with everincreasing and refined knowledge and is thought to bring a sense of fulfillment and well-being. The scientific mind is the apex of this worldview, having its roots in ancient Greece and a flourishing in the European Enlightenment of the 1700s. The modern mind is known for individualistic democracy, power, and emancipation. Inventiveness, endurance, will to succeed, and adventuresome spirit are sources for pride. The “miracles of modern medicine” are found here.

milestones of discovery and accomplishment: the harnessing of electricity and nuclear fission, for example. Generally, this equates with everincreasing and refined knowledge and is thought to bring a sense of fulfillment and well-being. The scientific mind is the apex of this worldview, having its roots in ancient Greece and a flourishing in the European Enlightenment of the 1700s. The modern mind is known for individualistic democracy, power, and emancipation. Inventiveness, endurance, will to succeed, and adventuresome spirit are sources for pride. The “miracles of modern medicine” are found here.

The second version of the evolution of human consciousness is the fall and tragic separation, which is a deep wounding or schism that separates humankind from nature. Manifestations of this version include exploitation of the natural environment, devastation of indigenous cultures, and an increasingly unhappy state of the human soul. Through the lens of tragic separation, humanity and nature are seen as having suffered grievously under an increasingly dualistic domination of thought and society. The worst consequences of this development are directly derived from the hegemony of modern industrial society and empowered by science and technology.

All individuals are challenged, although they may not recognize it, to reconcile these perspectives in their day-to-day lives. The two perspectives are both occurring simultaneously although not always at the level of awareness. For example, it is possible for a family to decide to maintain heroic life support systems, beyond all parameters of the natural dignity of dying, while their deeper desire is that their loved one be at peace. Both are apprehensions of a deeper, larger, and more complex story. Gain and loss have been working together simultaneously. As nurses, we are aware of pervasive and intense suffering, not only in our own inner work, but beyond, to the transpersonal and collective unconscious. Currently, the whole planet is in a transformative crisis.

Several core elements drive the multidimensional crisis. The modern mind—the mind of progress—originates in the worldview that there is a radical and irreconcilable distinction between the human self as subject and the world as object. In contrast, the primal worldview is that spirit or soul permeates the entire universe, within which the soul is embedded. The modern mind condemns this as a naive epistemologic error—childish, immature, and to be outgrown. The wisdom of the modern mind asserts that the human self is the exclusive repository of conscious intelligence; all meaning in the universe comes from the human subject. This is the classic existentialist assumption that, without humankind, the universe is meaningless.

Typically, a modern person’s allegiance is to science, in the belief that science rules the cosmos and objective world, while poetry, music, and spiritual strivings inhabit the internal world. Our cherished Western autonomy, offspring of the progress perspective, has been purchased at a staggering price: gradual dilution and diminution of soul, meaning, and spirit. Thus, the purpose of the entire world is exclusive to the human self. Everything else is “out there,” resulting in the demise of the metaphysical world and the disenchantment of the cosmos. Whether in conscious awareness or not, the greatest demand of modern time is to reconcile the imperatives of the two versions of what it means to be human. Must everyone choose and align themselves with one or the other? Must everyone consign themselves to an existence where “progress” is purchased with the coin of soul loss?

Modern culture itself is immersed in a rite of the most epochal and profound kind: the entire path of human civilization has taken humankind, the planet, and all its members into a trajectory of complete alienation that is part of the mythic death and rebirth story. Something new is being formed, however, that is a new participative and holistic vision of the universe amply reflected by contemporary scientific and philosophic insights. In this emerging view, the human self is both highly differentiated, yet reembedded in a participatory, meaning-laden universe. Throughout human history, all cultures have embedded within their collective psyche a connectedness to nature for survival of not only the human species but for the life of planet Earth.

Holistic nursing honors human history as part of our collective story that we carry in our cellular memory, with all its triumph and vulnerability. Holistic nurses strive for clarity of meaning, values, beliefs, and relationships.

The roots and intention of nursing in caring for others is to honor the totality of the individual and support creating environments that promote healing. Florence Nightingale, through her 13 canons, gave the most basic instruction of all: “The art of nursing requires us to alter the environment safely.”2 In Notes on Nursing, Florence Nightingale wrote, “No amount of medical knowledge will lessen the accountability for nurses to do what nurses do, that is, manage the environment to promote positive life processes.” This is our collective story as nurses, and it is the foundation on which nursing stands. Today, we are being called on and guided as 21st-century Nightingales to reclaim our highest aspirations, values, ethics, thought, and activity, to lead the way on this highest calling to heal our planet and all that dwell here today and for any foreseeable future.

The roots and intention of nursing in caring for others is to honor the totality of the individual and support creating environments that promote healing. Florence Nightingale, through her 13 canons, gave the most basic instruction of all: “The art of nursing requires us to alter the environment safely.”2 In Notes on Nursing, Florence Nightingale wrote, “No amount of medical knowledge will lessen the accountability for nurses to do what nurses do, that is, manage the environment to promote positive life processes.” This is our collective story as nurses, and it is the foundation on which nursing stands. Today, we are being called on and guided as 21st-century Nightingales to reclaim our highest aspirations, values, ethics, thought, and activity, to lead the way on this highest calling to heal our planet and all that dwell here today and for any foreseeable future.

Florence Nightingale as Environmentalist

Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, understood what we recognize today as ecological medicine and environmental health, involving the health of not only humans, but of all species and ecosystems with which we are connected physically, psychologically, and spiritually. Nurses have always been sensitive to environmental issues. Historically, nurses have been primarily concerned with health promotion, sanitation, and improvement in the quality of life for all people. Our modern world raises new issues and concerns for nurses, ranging from the use of increasingly toxic substances to high-technology machinery.

Dossey, in her seminal, scholarly works on Nightingale, delineates many of Nightingale’s tenets. One of these was “the precautionary principle.” It implies that when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures shall be taken, even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. The precautionary principle boils down to “better safe than sorry.” Nightingale wrote specifically on observations of hazards in the environment and the nurse’s responsibility: “If you think a patient is being poisoned by a copper kettle, cut off all possible connection to avoid further injury.”3 The essence of the precautionary principle is if there is a suspicion about a harmful environment or exposure, even though all of the evidence is not in, remove the person from the situation or stop the use of suspected harmful exposures.

Nightingale understood that nurses have a duty as well as an ethical and moral responsibility to take anticipatory actions to prevent harm; the burden of proof for a new technology, process, activity, or chemical lies with the proponents, not with the public. The precautionary principle always inquires about alternatives. Precautionary decision making is open, informed, and democratic and must include all affected parties. The first sentence of the Preface in Nightingale’s third edition of Notes on Hospitals (1863) reads as follows:

It may be a strange principle to enunciate as the very first requirement in a Hospital that it should do the sick no harm. It is quite necessary nevertheless to lay down such a principle, because the actual mortality in hospitals, especially in those of large crowded cities, is very much higher than any calculations founded on the mortality of the same class of patient treated out of hospitals would lead us to expect.

Dossey goes on to tell us that Nightingale doesn’t say a little harm or negligible harm; she says no harm. This anticipates the precautionary principle, which emphasizes that zero tolerance for the contamination of our environments is acceptable, not minimal or moderate contamination.4

Nightingale focused not only on problems, but sought solutions that guide us today. Nightingale engaged in what we today call risk assessment and on facts on which we base environmental decisions. Nurses are working with others to determine the degree of risk that is acceptable and asking questions such as “What is considered safe drinking water in hospitals and in homes?” “How much atmospheric pollution is safe in urban environments?” However, we must remember that the precautionary principle advocates zero degradation of the environment because of the uncertainty of risk assessment.5 Precautionary principle proponents and health policy analysts today advocate that it is incumbent on those introducing a new chemical or technology to demonstrate that it is safe, and not for the rest of us to prove it is harmful.6

Environmental initiatives and movements are part of a general societal intention to have a habitable planet, now and in years to come. These movements remain largely grassroots, or citizen driven, addressing impacts as they relate to humankind and Earth jurisprudence. Any benefit for the rest of the biotic community is a by-product from that frame of reference. The holistic outlook, as has been stated, recognizes all systems as interacting. If one part is affected, change of a greater or lesser magnitude occurs everywhere.

The roots of the environmental movement in the United States can be attributed to Native American cultures and traditions deeply honoring the feminine nurturing Earth for sustaining life for present and future generations. The conservation movement of the 1800s continued this tradition and was inspired by writers and artists such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson to preserve indigenous territories and the wilderness from the expansion of the times. As the vast American wilderness began to be explored, settled, and exploited, the idea that some wild spaces had to be preserved for future generations began to take on great significance. The national park system arose from this new awareness and declared land that could remain pristine as well as promote tourism. By 1916, the Interior Department was responsible for 14 national parks. There was not much societal activity for more than 50 years until the 1960s and 1970s, when activists elucidated the dangers of DDT and other hazardous materials—polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), mercury, lead, and other heavy metals. In 1976, the Environmental Protection Agency was established and environmental legislation and state and federal protection agencies widened the focus from preservation to protection and banned the pesticide DDT, what would later be classified as a “hormonal disruptor” and a carcinogen, and removed lead from paint in 1978.7

▪ ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS AND HEALTH

Since the 1970s, national attention has focused on efforts to clean up the nation’s environment and to ensure workers’ safety. Two federal agencies, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), were formed to monitor environmental concerns. In the 1980s, several states enacted right-to-know laws that require employers to notify employees of health hazards, to provide formal education regarding the safe use of toxic substances, and to keep medical records of those workers routinely exposed to specific toxic substances. Federal agencies were fully involved in public safety amid concerns about the fires and suspected presence of toxic materials in the rubble pile following the collapse of the World Trade Center (WTC) buildings on September 11, 2001.8 In addition, natural disaster environmental effects on health and established disaster management systems in place have been and continue to be evaluated and critiqued by diverse national agencies, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Office of Homeland Security.

In the early 1980s, the United States projected national health objectives for every decade. The latest of these documents, titled Healthy People 2020, is a set of health prevention goals that challenges health providers to strongly consider the environment’s effect on several health indicators. The environment can influence several of the indicators being targeted, and these include asthma, work-related assaults, lead exposure, needlestick injuries, noise-induced hearing loss, and worksite stress.9 These have implications for occupational risk exposure and possible prevention strategies.

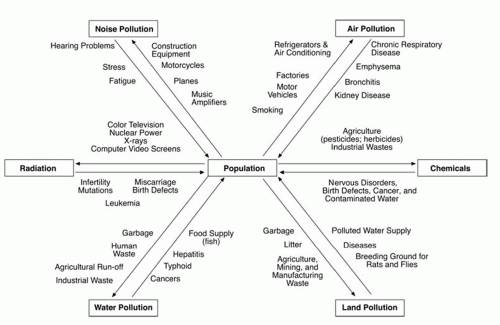

Environmental concerns range from eating contaminated poultry, hormone-fed beef, and irradiated fruits and vegetables to living near high-voltage power lines, understanding the Antarctic atmospheric ozone hole, the threat of nuclear power plants, and coping with other new high-technology hazards that we now fully acknowledge (Figure 29-1). Noise, lighting, air quality, space allocation, and workplace toxins have gained increasing attention as chronic stressors.

In the 1980s, the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica, along with escalating concern over global warming and climate change, introduced another phase of environmentalism, one that emphasized sustainability

and an awareness in protecting future generations from the dangers of exceeding nature’s ability to restore itself. Many people began to leave the cities, and a “back to the land” movement flourished. Other evolving perspectives addressed environmental justice and environmental ethics.

and an awareness in protecting future generations from the dangers of exceeding nature’s ability to restore itself. Many people began to leave the cities, and a “back to the land” movement flourished. Other evolving perspectives addressed environmental justice and environmental ethics.

Today, a new environmental movement is rising up following 50 years of “better living through chemistry” and is gathering momentum as baby boomers, exposed to chemicals over the course of their lifetime, are exhibiting epidemic rates of cancers and Alzheimer’s while those just beginning life are being plagued with learning disabilities, childhood cancers, and record rates of asthma and obesity. Chemicals are the basic building blocks that make up all living and nonliving things on Earth. Many chemicals occur naturally in the environment, and many more are man-made. Chemicals can enter the air, water, and soil when they are produced, used, or disposed. Chemicals are of concern because they can work their way into the food chain and accumulate and/or persist in the environment and in our bodies for many years.

Living in a Toxic World

In June 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a report Preventing disease through healthy environments— towards an estimate of the environmental burden of disease, the most comprehensive and systematic study yet undertaken on how preventable environmental hazards contribute to a wide range of diseases and injuries. By focusing on the environmental causes of disease, and how various diseases are influenced by environmental factors, the analysis breaks new ground in understanding the interactions between environment and health. The estimate reflects how much death, illness and disability could be realistically avoided every year as a result of better environmental management.

The report stated that nearly one-quarter of global disease is caused by environmental exposures, and “well targeted interventions can prevent much of the environmental risk,” saving suffering and millions of lives every year.10

Over the past century, humans have introduced a large number of chemical substances

into the environment; with the intention of creating “better living through chemistry”. Many of these substances are by-products of waste from industrial and agricultural processes. Today, chemical compounds are ubiquitous in our food, air, and water and have now found their way into every person and species. The bioaccumulation of these compounds is fueling metabolic and systemic dysfunctions and disease states. The systems most affected by these toxic compounds include the immune, neurological, and endocrine systems. This toxic “body burden” can trigger autoimmune reactivity, asthma, allergies, cancers, cognitive deficits, mood changes, neurological illness, reproductive dysfunction,10 glucose dysregulation, and obesity.11

into the environment; with the intention of creating “better living through chemistry”. Many of these substances are by-products of waste from industrial and agricultural processes. Today, chemical compounds are ubiquitous in our food, air, and water and have now found their way into every person and species. The bioaccumulation of these compounds is fueling metabolic and systemic dysfunctions and disease states. The systems most affected by these toxic compounds include the immune, neurological, and endocrine systems. This toxic “body burden” can trigger autoimmune reactivity, asthma, allergies, cancers, cognitive deficits, mood changes, neurological illness, reproductive dysfunction,10 glucose dysregulation, and obesity.11

We can no longer deny or avoid the environmental chaos that is occurring on a planetary level in these times. We read daily about nuclear disasters, global water crises, famines from loss of land, disappearance of the Earth’s rain forests, coastal devastation from toxic waste, climate change, and the long list of endangered species that could include humans, if actions are not taken soon.

To make a list of problems or to dwell on the environmental global crises is not a solution; a more life-affirming exercise is to clarify individual and collective goals for healing our planet, beginning with our individual actions and working toward attainable goals for oneself, family, and community. Human beings are characterized by the ability to choose and change; the same minds that have created the technology and our modern world can create new solutions. Rather than continue down our current environmental path, the past need not be perpetuated. Human beings can elect and select life-affirming ways, use their inventive genius to reinvent a world that can sustain present and future generations, nurturing ourselves physically, mentally, and spiritually.

A very different world could be created by using alternative strategies and technologies that could offer the same essential services that chemicals and current energy sources provide.

Our Environmental Story

In less than one lifetime, production of synthetic organic chemicals (e.g., dyes, plastics, pesticides, and solvents) has increased more than 1,000-fold in the United States alone. According to the National Toxicology Program, more than 80,000 chemicals are registered for use in the United States. Each year, an estimated 2,000 new ones are introduced for use in such everyday items as foods, personal care products, prescription drugs, household cleaners, and lawn care products, and most are never tested for their impact on human health. In addition, many chemicals are emitted as by-products of production or incineration (particularly relevant to the hospital industry). Some chemicals, such as life-saving medications, can have direct health benefits. Others, such as pesticides and herbicides, are designed to be usefully lethal. The most pernicious and pervasive were not meant to come into human contact. When PCBs were created in 1929, for example, they were intended for use only in electrical wiring, lubricants, and liquid seals. Although many chemicals, including DDT and PCBs, have been banned by the Environmental Protection Agency since 1978, they can still be found in human blood samples today along with 250 other synthetic chemicals in the bodies of almost everyone in the industrial world. A recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conservatively estimates that Americans of all ages carry a body burden of at least 148 chemicals, some of them banned for decades.12

Many chemicals in use today have not yet been classified as harmful to human health, although recent reports based on current research are sounding the alarm and many organizations are hopeful that consumer activism will gain momentum and fuel legislation for formulating a new environmental and public health policy.

One of the reasons that it is difficult to study the link between environmental conditions and illness or disease is that there are so many intervening variables. Hundreds of substances along with lifestyle factors and individual genetic pre-dispositions are involved. The emerging scientific inquiry in the field of epigenetics provides new insights into how our genes are influenced to express themselves under environmental stress. Furthermore, not all toxic substances and environmental conditions induce immediate untoward reactions; many toxins seem to

cause disease later, perhaps years after the initial exposure. Many chemical substances do not appear harmful at low-level exposures, but it is not well understood how small amounts of repeated chemical exposures when combined with other substances work synergistically over time. Breathing asbestos fibers, for example, seldom causes immediate symptoms, but often has resulted in serious chronic disease many years later. Environmental elements known to be hazardous include lead, cigarette smoke, silica, benzene, mercury, chlorine, formaldehyde, poor lighting, stress, and noise. Converging themes from the fields of environmental health and human ecology and health highlight opportunities for innovation and advancement in environmental health theory, research, and practice.13

cause disease later, perhaps years after the initial exposure. Many chemical substances do not appear harmful at low-level exposures, but it is not well understood how small amounts of repeated chemical exposures when combined with other substances work synergistically over time. Breathing asbestos fibers, for example, seldom causes immediate symptoms, but often has resulted in serious chronic disease many years later. Environmental elements known to be hazardous include lead, cigarette smoke, silica, benzene, mercury, chlorine, formaldehyde, poor lighting, stress, and noise. Converging themes from the fields of environmental health and human ecology and health highlight opportunities for innovation and advancement in environmental health theory, research, and practice.13

The Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals 2009 and the Updated Tables, released in February 2011, together are the most comprehensive assessment of environmental chemical exposure in the U.S. population. The Fourth Report includes the findings from national samples for 1999-2000, 2001-2002, and 2003-2004. The blood and urine samples were collected from participants in the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which obtains and releases health-related data from a nationally representative sample in 2-year cycles. For the first time, the CDC has tracked national exposure levels of the U.S. population for 27 different substances—some to be proven carcinogens. The CDC report expresses hopes the data will help public health officials better understand the relationship between chemical exposures and health consequences—and to ultimately help legislate for more effective public policy decisions.14

In June 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services added formaldehyde, styrene, and six other substances to its Report on Carcinogens after scientists discovered that exposure to the substances can increase the risk of developing certain cancers. Formaldehyde is a colorless, flammable, strong-smelling chemical widely used to make resins for household items, such as composite wood products, paper product coatings, plastics, synthetic fibers, and textile finishes. It is also commonly used as a preservative in medical laboratories, mortuaries, and some consumer products, including hairstraightening products.

A number of cohort studies involving workers exposed to formaldehyde have recently been completed. One study, conducted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), looked at 25,619 workers in industries with the potential for occupational formaldehyde exposure and estimated each worker’s exposure to the chemical while at work . The results showed an increased risk of death due to leukemia, particularly myeloid leukemia, among workers exposed to formaldehyde.15

Children’s Health

We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children.

—Native American Proverb

Childhood is a sequence of life stages from conception through fetal development, infancy, and adolescence, as defined by the Environmental Protection Agency. Children are the most vulnerable to environmental exposures for the following reasons:

Their bodily systems are still developing.

They eat more, drink more, and breathe more in proportion to their body size.

Their behaviors can expose them more to chemicals and organisms (e.g., crawling on the ground).

Dr. Phillip Landrigan, director of the Children’s Environmental Health Center, dean for Global Health, chair of Preventive Medicine, professor of Pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and an international leader on children’s health and the environment, has written extensively and advocated for updated federal regulation of pesticides in food. He has repeatedly expressed that the public is rightly concerned about possible health impacts from frequent exposures through our food supply. He reports on a trio of peer-reviewed studies published June 2011 that found children exposed in the womb to high levels of a class of pesticides known as organophosphates had lower average intelligence than other children by the time they reached age 7 years. Researchers found that exposure during pregnancy may impair a child’s

cognitive development. “If exposure to pesticides are harming children, it doesn’t matter if the levels are below the legal limit set by the government,” says Landrigan, whose research in the 1990s compelled the federal government to tighten pesticide standards significantly.16 Since that time, new and more potent pesticides have been introduced to the global market, including a new generation of pesticide-induced genetically modified organisms to “protect” crops from external threats. Research on the threat to the health of humans and other species with this new technology has many researchers and scientists apprehensive about the potential deleterious effects.17 Dr. Landrigan and Lynn R. Goldman, dean of the School of Public Health at George Washington University, have proposed a three-pronged approach to reduce the burden of disease and rein in the effects of toxic chemicals in the environment:

cognitive development. “If exposure to pesticides are harming children, it doesn’t matter if the levels are below the legal limit set by the government,” says Landrigan, whose research in the 1990s compelled the federal government to tighten pesticide standards significantly.16 Since that time, new and more potent pesticides have been introduced to the global market, including a new generation of pesticide-induced genetically modified organisms to “protect” crops from external threats. Research on the threat to the health of humans and other species with this new technology has many researchers and scientists apprehensive about the potential deleterious effects.17 Dr. Landrigan and Lynn R. Goldman, dean of the School of Public Health at George Washington University, have proposed a three-pronged approach to reduce the burden of disease and rein in the effects of toxic chemicals in the environment:

Conduct a requisite examination of chemicals already on the market for potential toxicity, starting with the chemicals in widest use, using new, more efficient toxicity testing technologies.

Assess all new chemicals for toxicity before they are allowed to enter the marketplace, and maintain strictly enforced regulation on these chemicals.

Bolster ongoing research and epidemiologic monitoring to better understand, and subsequently prevent, the health impact of chemicals on children.

Pesticide exposure in our food supply is not only associated with neurological and learning disabilities. Increasingly, research studies show increased risk of several types of cancers from airborne exposure via pesticide drift, including brain cancer from home pesticide and insecticide use, leukemia from home and garden pesticides, and nonlymphocytic leukemia from extermination use.18 The authors report positive associations with exposures during pregnancy to pesticides, insecticides, and herbicides, and positive associations with childhood exposures to pesticides and insecticides. It has long been established that many pesticides cause cancer in animals. A new study finds that children who live in homes where their parents use pesticides are twice as likely to develop brain cancer versus those who live in residences in which no pesticides are used. It appears to cause an elevated risk for certain types of cancers and positive associations with exposures during pregnancy to pesticides, insecticides, and herbicides, and positive associations with childhood exposures to pesticides and insecticides, and leukemias.19 The risk of childhood brain cancer increases with exposures received from either parent. Studies show that risk was significantly lower with fathers who washed immediately after the pesticide exposure or wore protective clothing versus those who never or only sometimes took precautions. The parents assessed in this study were generally in contact with the pesticides through residential exposure, including lawn and garden care.20,21,22

In an earlier study spearheaded by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in collaboration with the American Red Cross, two medical laboratories found an average of 200 industrial chemicals and pollutants in the umbilical cord blood of 10 babies born in U.S. hospitals between August and September 2004. Tests revealed a total of 287 different chemicals in the group. The umbilical cord blood of these 10 children, collected by Red Cross after the cord was cut, harbored pesticides, consumer product ingredients, and wastes from burning coal, gasoline, and garbage. This study represents the first reported cord blood tests for targeted chemicals and the first reported detections in cord blood for multiple compounds. Among those found were eight perfluorochemicals used as stain and oil repellents in fast-food packaging, clothes, and textiles—including the Teflon chemical PFOA, recently characterized as a likely human carcinogen by the EPA’s Science Advisory Board—; dozens of widely used brominated flame retardants and their toxic by-products; and numerous pesticides and plastics including bisphenol A. Of the 287 chemicals detected in umbilical cord blood, 180 have been shown to cause cancer in humans or animals, 217 are toxic to the brain and nervous system, and 208 cause birth defects or abnormal development in animal tests. The dangers of pre- or postnatal exposure to this complex mixture of carcinogens,

developmental toxins, and neurotoxins have never been studied.23,24

developmental toxins, and neurotoxins have never been studied.23,24

Endocrine Disruptors

Human beings and animals are most vulnerable to hormonal disruption during prenatal development when a fetus is undergoing rapid, hormonally orchestrated change. Other critical windows of development when the endocrine system is particularly sensitive to hormonal disruption include early life, puberty, pregnancy, and lactation.25

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), endocrine disruptors are chemicals that may interfere with the body’s endocrine system and produce adverse developmental, reproductive, neurological, and immune effects in both humans and wildlife. Endocrine disruptors may pose the greatest risk during prenatal and early postnatal development when organ and neural systems are forming. Diethylstilbesterol (DES), a drug with strong estrogenic properties administered to pregnant women until 1971 to prevent miscarriages, is a tragic example. Female children of mothers who took DES during pregnancy have a higher incidence of certain forms of ovarian, cervical, and vaginal cancer.26

A wide range of substances, both natural and man-made, is thought to cause endocrine disruption, including pharmaceuticals, polychlorinated biphenyls, DDT, dieldrin, atrazine and other pesticides and herbicides, and plasticizers such as bisphenol A and phthalates. Endocrine disruptors are found in many everyday products, including plastic bottles, metal food cans, detergents, flame retardants, food, toys, cosmetics, pesticides, and industrial chemicals and by-products such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, and phenols. Many endocrine disruptors affect sex hormone function and reproduction, according to the findings of multigeneration animal studies. The full effects of endocrine disruptors are not completely understood because they have been around only for a few generations. A recently published article in Environmental Health Perspectives reports the conclusions of an international research team on the current science related to early-life environmental exposures and mammary gland development, preconception, in utero development, childhood, and reproductive years.27

In 2009, at its 91st annual meeting, the Endocrine Society, a research-based medical association, issued a strong statement citing the science on the adverse effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals and offered guidelines and recommendations intended to educate and increase awareness. According to Robert M. Carey, president of the Endocrine Society and professor of medicine at the University of Virginia, “Endocrine-disrupting chemicals interfere with hormone biosynthesis, metabolism and action resulting in adverse developmental, reproductive, neurological and immune effects in humans and wildlife. Endocrine disrupting chemicals include substances in our environment, food and consumer products.”28

One such chemical described in the statement, bisphenol A, a chemical that permeates our lives, is widely used in the manufacturing of plastics including baby bottles, toys, and metal cans. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, 95% of Americans have detectable levels of bisphenol A in their bodies. In a recent CDC study, the observed BPA levels detected—0.1 to 9 parts per billion (ppb)—were at and above the concentrations known to reliably cause adverse effects in laboratory experiments

The evidence of the mechanisms of action and the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on male and female reproduction, thyroid function, metabolism, and obesity are well documented.28

Known to be estrogenic since the mid-1930s, BPA serves as a chemical building block and a polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resin in technology applications, paints and adhesives, and as a protective coating in many products. For more than 20 years, researchers in the scientific community have expressed concerns about its safety in consumer products.29 In September 2010, Canada and, soon thereafter, the European Union declared BPA a toxic substance and banned BPA use in baby bottles, expressing fears that it may harm the health of children.30 Numerous studies indicate that the chemical leaches into food and disrupts hormones. States including Maine, New York, and Minnesota have

introduced legislation to ban children’s products containing BPA. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released information to help parents reduce children’s BPA exposures. In 2010, in response to consumer concerns, Walmart banned BPA plastic baby bottles, and General Mills, a major corporation in the food industry, is currently seeking new technology to make canned food products without BPA.

introduced legislation to ban children’s products containing BPA. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released information to help parents reduce children’s BPA exposures. In 2010, in response to consumer concerns, Walmart banned BPA plastic baby bottles, and General Mills, a major corporation in the food industry, is currently seeking new technology to make canned food products without BPA.

After being pressed to reevaluate its position by the National Toxicology Program, in January 2010, the FDA expressed “some concern” about the potential effects of BPA on the “brain, behavior, and prostate gland in fetuses, infants, and young children.” The agency states that it will not issue a ban on BPA. The American Chemistry Council (ACC) position supports the FDA’s decision, insisting that a ban on BPA is unnecessary. According to the ACC, research indicates that BPA is “perfectly safe.”31

Prenatal exposure of rats to BPA results in increases in the number of precancerous lesions and in situ tumors (carcinomas) as well as increased number of mammary tumors following adulthood exposures to subthreshold doses (lower than that needed to induce tumors) of known carcinogens. Epigenetic changes in mammary tissue were measured following several generations. Exposures to BPA in adulthood also enhance the rate of growth and proliferation of existing hormone-sensitive mammary tumors, suggesting multiple mechanisms by which BPA may affect breast cancer development. This suggests that exposures to bisphenol A in utero is a predictor of breast cancer in adulthood.32

Women’s Health

Over the past few years, leading researchers specializing in issues related to hormone disruption and women’s reproductive health have convened to address why conception rates fell 44% in the United States between 1960 and 2002.33 Hormone disruptors can affect both parents, and scientists have linked fertility problems to exposure to BPA, DDT, DES, cigarette smoke, and PCBs.34 Early puberty, known as precocious puberty in the scientific literature, is another growing concern. The onset of the age of puberty has declined over the last half century, and girls today begin to develop breast buds 2 years earlier than they did 40 years ago. Girls who go through puberty early have increased risk for depression, obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, breast cancer, and experimentation with sex and drugs at a younger age. The hormonal cues that initiate the onset of puberty are sensitive to a variety of environmental influences.35 Prepubertal stages of development, such as in the womb and early life, are thought to be vulnerable windows for triggers of hormonal disruption. In human studies, early puberty is linked to greater cumulative estrogenic exposure to multiple contaminants, such as phthalates, BPA, and organochlorine pesticides among others.36

Pesticides Permeate Our World

Atrazine, a potent endocrine disruptor chemical, is the most common herbicide used globally. In the United States, 34 million kilograms of atrazine are used yearly, mostly on cotton, corn, sorghum, sugarcane, pineapple, Christmas trees, and golf course greens. Atrazine poses serious health safety concerns, and the chemical has been banned by the European Union, and even Switzerland, where atrazine’s leading manufacturer is headquartered. Atrazine is an organic compound in the triazine family of herbicides. It has been shown to inhibit electron transport, which then blocks photosynthesis. Increased concern about the safety of atrazine arose after monitoring programs found the chemical in drinking water and several scientific studies demonstrated the pollutant’s ability to emasculate amphibians and fish. Male frogs were found to have egg sacs and other abnormal sexual characteristics. More recent studies have shown an association with birth defects in male newborns including hypospadias. In view of several compelling scientific studies, the EPA is reinvestigating atrazine, although the industry denies all reports. In 2009, the National Resource Defense Council (NRDC) analyzed results of surface water and drinking water monitoring data for atrazine and found pervasive contamination of watersheds and drinking water systems across the Midwest and southern United States.37

Early Child Development

Environmental factors during pregnancy might play a larger role than genetics in the development of autism spectrum disorders, according to two studies in the Archives of General Psychiatry. In one study, researchers at Stanford University

and the University of California at San Francisco found that genetics account for about 38% of the risk of autism and that environmental factors account for about 62%. In a second study, researchers from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system found that children faced a higher risk of autism if their mothers took antidepressants during the year prior to giving birth. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 13% of children have a developmental disability, ranging from language and speech impairments to serious developmental problems classified along the autism spectrum disorder.

and the University of California at San Francisco found that genetics account for about 38% of the risk of autism and that environmental factors account for about 62%. In a second study, researchers from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system found that children faced a higher risk of autism if their mothers took antidepressants during the year prior to giving birth. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 13% of children have a developmental disability, ranging from language and speech impairments to serious developmental problems classified along the autism spectrum disorder.

The role of environmental factors in the development of autism is a crucial area of study. Along with genetics, the increase in autism cases has generated extreme concern over potential epigenetic changes when prenatal exposures are combined with specific genetic codes.

A recent study conducted by Harvard School of Public Health and published in the journal Pediatrics links dietary pesticide exposure to attention deficit disorders in children. The study followed more than 1,000 children and found 94% of them had pesticide residues in their urine. Those with the highest levels were nearly twice as likely to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).38 The pesticide class analyzed was the common and widely used organophosphates (OPs), known to be toxic because they work by disabling a nerve chemical used to transmit signals.39 In the study, the fruits with the highest concentration of pesticides included commercial strawberries, raspberries, and frozen blueberries. Researchers write that this study is important for two reasons. First, it examined children with average exposure (not those with increased exposure such as children of farm workers); second, it shows that even small and allowable amounts of pesticides can have significant effects on a young person’s brain. Children are at increased risk because they are exposed to higher levels of chemicals relative to their body size and their detoxification abilities are less developed. Dr. Susan Kegley, consulting scientist with Pesticide Action Network, explains:

When it comes to pesticides, children are among the most vulnerable—pound for pound, they drink 2.5 times more water, eat 3-4 times more food, and breathe twice as much air as adults. They also face exposure in the womb and via breast milk. Add to this the fact that children are unable to detoxify some chemicals and you begin to understand just how vulnerable early childhood development is. We’ve known for a long time that OP’s poison farm workers at higher doses, and now we have a window into their lower-dose effects on the broader population.40

In May 2011, U.S. pediatricians called for Congress to overhaul a failed federal law that has exposed millions of children, beginning in the womb, to an untold number of toxic chemicals. In its statement, Chemical-Management Policy: Prioritizing Children’s Health, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act be “substantially revised” because it has “been ineffective in protecting children, pregnant women, and the general population from hazardous chemicals in the marketplace.”41,42,43

As researchers study the impact of pesticides on health and the environment, analysts and consumers demand safer food products. The U.S. Department of Agriculture issues an annual report on the amount of pesticide residue it detects in samples of fresh fruits and vegetables around the country. The Environmental Protection Agency uses the data to monitor exposure to pesticides and enforce federal standards designed to protect infants, children, and other vulnerable people. But the 200-page annual report has become a target of a lobbying campaign by the commercial produce industry, which worries that the data are being misinterpreted by the public. Eighteen produce trade associations have written to complain that the data have “been subject to misinterpretation by activists, which publicize their distorted findings through national media outlets in a way that is misleading for consumers and can be highly detrimental to the growers of these commodities.”44 In 2010, sales of organic fruits and vegetables, which are grown without synthetic chemicals, increased rapidly. Organic produce purchases now make up 12% of all U.S. fruit and vegetable sales, according to the Organic Trade Association. Even during the

economic downturn, organic fruit and vegetable sales reached nearly $10.6 billion in 2010, up nearly 12% from 2009.44

economic downturn, organic fruit and vegetable sales reached nearly $10.6 billion in 2010, up nearly 12% from 2009.44

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer incidence rates in the United States increased more than 40% between 1973 and 1998. In 2008, a women’s lifetime risk of breast cancer was 1 in 8. Breast cancer arises from genetic, lifestyle, and environmental causes, several of which relate to lifetime exposure to hormones.44

Contrary to popular belief, only about 5% of women diagnosed with breast cancer have a link to the “breast cancer gene.” Contributing factors that increase breast cancer risk include having children late in life and early onset of puberty. Exposure to radiation from chest x-rays during childhood and taking hormone replacement therapy are also known risk factors, along with alcohol abuse, tobacco exposure, and second-hand smoke exposure. Breast cancer rates are higher in women who are obese and women who gain excess weight during adulthood. Yet, the vast majority of women will never know the cause of their disease. The degree of alarm within the scientific community concerning the dangers of hormone-disrupting environmental pollutants as major contributors to breast cancer in younger women was evident when Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL), a European umbrella group of nongovernmental research organizations, released a report in 2010 stating, “We will not be able to reduce the risk of breast cancer without addressing preventable causes, particularly exposure to chemicals.”45

Prevention is a solution that requires addressing the real issues surrounding the global increase in breast cancer and all cancers. Public health education, corporate responsibility, and governmental regulation of harmful chemicals must be included in addressing rising rates of cancer. According to the latest research, cumulative toxic exposures often beginning in utero show clear links to increased risks for breast cancer later in life.46

Research also links the role of the environment to the rise in testicular and prostate cancers in men.47 To compound the problem of our toxic environment, we refine and process away much of the nutritional value in our food supply and replace it with imitation foods lacking protective phytonutrients that can filter, neutralize, and detoxify many of these potentially harmful chemicals. Products too often are filled with artificial colorings, preservatives, flavorings, and many unlisted industrial ingredients. Our modern poor-quality diet, combined with agricultural pesticides and animals being raised on antibiotics, chemical feed, and growth hormones, may dispose many of us to a toxic body burden, stressing the body’s ability to detoxify and eliminate these products. According to Dr. Walter Willett at the Harvard School of Public Health and the American Institute for Cancer Research, a review of 4,500 scientific studies on diet and nutrition concludes in a 650-page report that 40% of cancers are avoidable. The document states, “The bottom line: eat a plant based diet, maintain moderate weight throughout life, and get some exercise.”

The most challenging aspect to creating healthier environments includes discovering how to eliminate many of these compounds from the environment. The good news is that cancer and other health problems can be reduced by lifestyle interventions that can lower exposures to environmental toxicants and enhance our innate immune surveillance systems, increasing cellular energy for healthy metabolism and improving detoxification pathways through nutrition, stress reduction, and exercise.47,48

The following list shows the everyday products that contain endocrine disruptors that people can try to avoid or eliminate from their lives when possible:

Pesticides, herbicides, including pesticide residues in soil

Dry cleaning chemicals

Solvents: paints, varnishes, cleaning fluids

Spermicidal contraceptives and treated condoms

Perfume fragrances, air fresheners, cleaning fragrances

Car exhaust, car interiors—especially that “new car smell”: (off-gassing)

Plastics, plastic baby bottles, plastic food storage containers, Styrofoam, tin cans (BPA lining)

PVC plumbing pipes

Pharmaceutical runoff in the water supply

BHA and BHT, common food preservatives

FD&C Red No. 3, a common food dye (erythrosine)

Personal care products that contain parabens, phthalates

Scientists and advocacy groups are informing the public and advocating for the precautionary principle while demanding health policy actions and regulation of the chemical industry.

Following is a review of the prevention strategies that can be implemented:

Choose your food wisely; eat organically grown and raised foods when possible.

Limit intake of animal fats because endocrine disruptors and heavy metals accumulate in the food chain and are stored in fat. The higher the intake of commercially raised animal products, the greater the potential for increasing toxic load.

Choose seasonal and local foods.

Monitor fish consumption. Large, deepwater “fatty” fish such as tuna and swordfish may contain higher levels of synthetic chemicals and heavy metals, so eat them infrequently. Better choices are wild-caught salmon, sardines, cod.

Avoid pesticides. If you can’t buy all organic food, try to pick and choose. Certain crops are more heavily treated than others are. The Environmental Working Group database (www.ewg.org) offers guidelines on the fruits and vegetables containing both the highest pesticide residues and the lowest. Produce containing the highest pesticide levels include peaches, apples, bell peppers, celery, nectarines, strawberries, cherries, lettuce, grapes, pears, spinach, and potatoes. Wash all fruits and vegetables thoroughly before consuming, or peel them if they are not organically grown.

Support your body’s natural ability to detoxify by exercising and sweating on a regular basis. Use a sauna or steam bath. Get regular sleep (you detoxify at night) and drink plenty of clean or filtered water.

Consume plenty of fiber, which is found in whole grains, beans, vegetables, fruits, seeds (flax), and nuts.

Drink beverages such as green tea that contain antioxidants and phytonutrients that can assist the body to rid itself of toxins.

If planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding, be vigilant about chemicals and eliminate as many as possible for 1 year prior to conception. Guidelines for pregnant women on eating fish are listed at www.americanpregnancy.org/pregnancyhealth/fishmercury.htm.

Become an environmental detective. Investigate the chemicals in your home, work, and community environments.

Know your water supply. Find out whether your local community’s water testing program checks for hormone-disrupting chemicals and heavy metals. Not all household filters work effectively on chemicals and, unfortunately, not all bottled water is checked either. Read water quality reports. If you drink purified water out of plastic bottles, do not leave the bottles in the car or the hot sun for any length of time; heat activates the molecules in the plastic, which increases the rate at which the polycarbons leach into the water.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access