Endocrine care

Diseases

Adrenal hypofunction

Adrenal hypofunction, also called adrenal insufficiency, may be classified as primary or secondary. Primary adrenal hypofunction (Addison’s disease) originates within the adrenal gland and is characterized by decreased mineralocorticoid, glucocorticoid, and androgen secretion. A relatively uncommon disorder, Addison’s disease occurs in people of all ages and both sexes. Adrenal hypofunction may also occur secondary to a disorder outside the gland, such as with a pituitary tumor with corticotropin deficiency, but, unlike the primary form, aldosterone secretion remains unaffected.

With early diagnosis and adequate replacement therapy, the prognosis for both forms of adrenal hypofunction is promising.

Adrenal crisis—also called addisonian crisis—is a critical deficiency of mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids that generally follows acute stress, sepsis, trauma, surgery, or the discontinuation of steroid therapy. Adrenal crisis is a medical emergency that necessitates immediate, vigorous treatment.

Signs and symptoms

Confusion, depression, delirium, and possibly psychosis

Bronze coloration of the skin that resembles a deep suntan, especially in the creases of the hands and over the metacarpophalangeal joints, elbows, and knees (Addison’s disease)

Cravings for salty food

Decreased tolerance for even minor stress

Dry skin and mucous membranes

Fatigue

Hypotension

Light-headedness (when rising from a chair or bed)

Muscle weakness, myalgia, arthralgia

Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, chronic diarrhea, and weight loss

Poor coordination

Weak, irregular pulse

Decreased pubic hair, diminished libido, and amenorrhea in women

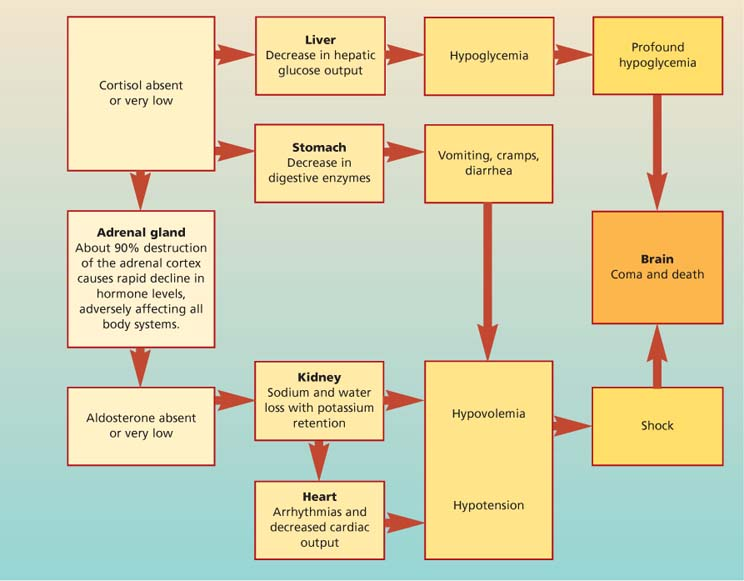

How adrenal crisis develops

How adrenal crisis developsAdrenal crisis is the most serious complication of adrenal hypofunction. It can occur gradually or with catastrophic suddenness, making prompt emergency treatment essential. It’s also known as acute adrenal insufficiency.

This potentially lethal condition usually develops in a patient who doesn’t respond to hormone replacement therapy, undergoes marked stress without adequate glucocorticoid replacement, or abruptly stops hormonal therapy. It can also result from trauma, bilateral adrenalectomy, or adrenal gland thrombosis after a severe infection (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome).

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of adrenal crisis include profound weakness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, hypotension, dehydration and, occasionally, high fever followed by hypothermia. If untreated, this condition can ultimately cause vascular collapse, renal shutdown, coma, and death.

The flowchart (shown at right) summarizes what happens in adrenal crisis and pinpoints its warning signs and symptoms.

Treatment

Primary and secondary adrenal hypofunction

Adrenal crisis

I.V. bolus administration of dexamethasone followed by an I.V. bolus of hydrocortisone.

To correct hypovolemia: infusion of 3 to 5 L of I.V. normal saline or 5% dextrose solution during the acute stage

After the crisis, maintenance doses of hydrocortisone to preserve physiologic stability

Nursing considerations

In adrenal crisis, monitor vital signs carefully, especially for hypotension, volume depletion, and other signs of shock. Check for decreased level of consciousness and reduced urine output, which may also signal shock. Monitor for hyperkalemia before treatment and for hypokalemia afterward (from excessive mineralocorticoid effect). Check for cardiac arrhythmias.

Check blood glucose levels regularly because steroid replacement may increase levels.

Record weight and intake and output carefully because the patient may have volume depletion. Until onset of mineralocorticoid effect, force fluids to replace excessive fluid loss.

Patients on maintenance steroid therapy

Control the environment to prevent stress. Encourage the patient to use relaxation techniques.

Encourage the patient to dress in layers to retain body heat, and adjust room temperature, as indicated.

Provide good skin care. Use alcohol-free skin care products and an emollient lotion after bathing. Turn and reposition the bedridden patient every 2 hours. Avoid pressure over bony prominences.

Use protective measures to minimize the risk of infection, if necessary. Limit the patient’s visitors if they have infectious conditions. Use meticulous hand-washing technique.

Consult with a dietitian to plan a diet that maintains sodium and potassium balances and provides adequate protein and carbohydrates.

Watch for cushingoid signs, such as fluid retention around the eyes and face. Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance, especially if the patient is receiving mineralocorticoids. Monitor weight and check blood pressure to assess body fluid status. Check for petechiae because these patients bruise easily.

In women receiving testosterone injections, watch for and report facial hair growth and other signs of masculinization.

If the patient is receiving only glucocorticoids, observe for orthostatic hypotension or abnormal serum electrolyte levels, which may indicate a need for mineralocorticoid therapy.

Teaching about adrenal hypofunction

Teaching about adrenal hypofunction

Explain that lifelong steroid therapy is necessary. Teach the patient and his family to identify and report signs and symptoms of drug overdose (weight gain and edema) or underdose (fatigue, weakness, and dizziness).

Advise the patient that he needs to increase the dosage during times of stress (when he has a cold, for example). Warn that infection, injury, or profuse sweating in hot weather can precipitate adrenal crisis. Caution him not to abruptly discontinue the medication because this can also cause adrenal crisis.

Instruct the patient to always carry a medical identification card stating that he takes a steroid and giving the name and dosage of the drug. Teach him and his family how to give an injection of hydrocortisone and advise them to keep an emergency kit available that contains a prepared syringe of hydrocortisone to use in times of stress.

Instruct the patient to take steroids with antacids or meals to minimize gastric irritation. Suggest taking two-thirds of the dosage in the morning and the remaining one-third in the early afternoon to mimic diurnal adrenal secretion.

Inform the patient and his family that the disease causes mood swings and changes in mental status, which steroid replacement therapy can correct.

Review protective measures to decrease stress and help prevent infections. For example, the patient should get adequate rest, avoid fatigue, eat a balanced diet, and avoid people with infections. Also be sure to provide instructions for stress management and relaxation techniques.

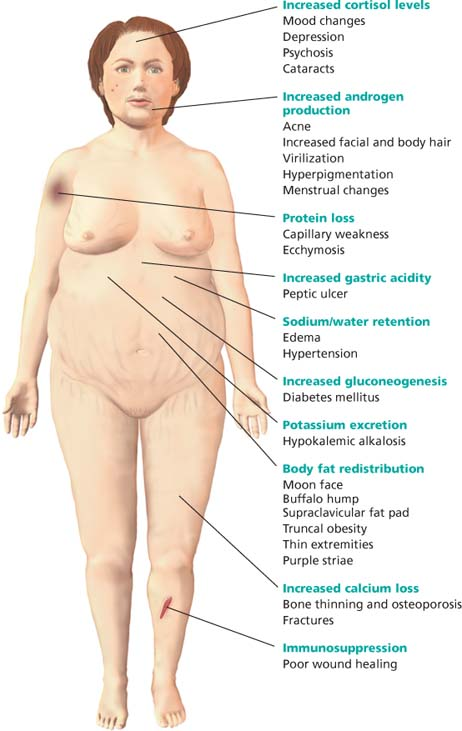

Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome is the clinical manifestation of glucocorticoid (particularly cortisol) excess. Excess secretions of mineralocorticoids and androgens may also cause Cushing’s syndrome. In about 70% of patients, Cushing’s syndrome results from excess production of corticotropin and consequent hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex.

The disorder is classified as primary, secondary, or iatrogenic, depending on its cause, and is most common in females.

The hallmark signs of Cushing’s syndrome include adiposity of the face, neck, and trunk, and purple striae on the skin. The nature of the prognosis depends largely on early diagnosis, identification of the underlying cause, and effective treatment.

Signs and symptoms

Fatigue

Muscle weakness

Sleep disturbances

Water retention

Amenorrhea

Decreased libido

Irritability

Emotional instability

Thin hair

Moon-shaped face

Hirsutism

Acne

Buffalo humplike back

Thin extremities

Petechiae, ecchymoses, and purplish striae

Delayed wound healing

Swollen ankles

Hypertension

Treatment

Possibly, radiation, drug therapy, or surgery to restore hormone balance and reverse Cushing’s syndrome

Transsphenoidal microadenomectomy

Pituitary irradiation

Bilateral adrenalectomy

In a patient with a nonendocrine corticotropin-producing tumor, excision of the tumor, followed by drug therapy with mitotane, metyrapone, or aminoglutethimide

Lifelong steroid replacement therapy

Nursing considerations

Keep accurate records of vital signs, fluid intake, urine output, and weight. Monitor serum electrolyte levels daily.

Consult a dietitian to plan a diet high in protein and potassium and low in calories, carbohydrates, and sodium.

Use protective measures to reduce the risk of infection, if necessary. Use meticulous hand-washing technique.

Schedule activities around the patient’s rest periods to avoid fatigue. Gradually increase activity, as toler-ated.

Institute safety precautions to minimize the risk of injury from falls.

Help the bedridden patient turn every 2 hours. Use extreme caution while moving the patient to minimize skin trauma and bone stress. Provide frequent skin care, especially over bony prominences. Provide support with pillows and a convoluted foam mattress.

Encourage the patient to verbalize feelings about body image changes and sexual dysfunction. Offer emotional support and a positive, realistic assessment of the patient’s condition. Help the patient to develop coping strategies. Refer to a mental health professional for additional counseling, if necessary.

Teaching about Cushing’s syndrome

Teaching about Cushing’s syndrome

Advise the patient that lifelong steroid replacement is necessary. Teach the patient and family members to identify and report signs of drug overdose (edema and weight gain) or underdose (fatigue, weakness, and dizziness). Tell the patient not to abruptly discontinue the drug because this may precipitate adrenal crisis.

Instruct the patient to take steroids with antacids or meals to minimize gastric irritation. Advise taking two-thirds of a dose in the morning and the remaining third in the early afternoon to mimic diurnal adrenal secretion.

Encourage the patient to wear a medical identification bracelet and carry medication at all times.

Teach the patient protective measures to decrease stress and infections: for example, get adequate rest and avoid fatigue, eat a balanced diet, and avoid people with infections. Also teach relaxation and stress-reduction techniques.

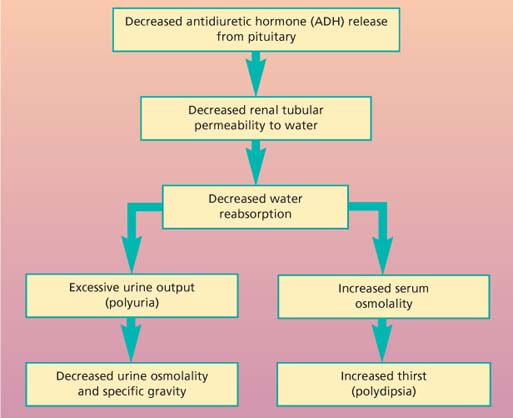

Diabetes insipidus

A disorder of water metabolism, diabetes insipidus results from a deficiency of circulating vasopressin (also called antidiuretic hormone, or ADH), a resistance to vasopressin at the receptor sites in the kidneys, or an abnormal thirst mechanism. A decrease in ADH levels leads to altered intracellular and extracellular fluid control, causing renal excretion of a large amount of urine. Diabetes insipidus can strike people of all ages, from infancy to adulthood.

In uncomplicated diabetes insipidus and with adequate water replacement, the prognosis is good and patients usually can lead normal lives. However, in cases complicated by an underlying disorder, such as cancer, the prognosis is variable.

Signs and symptoms

Extreme polyuria (usually 4 to 16 L/day of dilute urine, but sometimes as much as 30 L/day)

Extreme thirst

Weight loss

Dizziness

Weakness

Constipation

Slight to moderate nocturia

Dry skin and mucous membranes

Fever

Dyspnea

Pale and voluminous urine

Poor skin turgor

Tachycardia

Decreased muscle strength

Hypotension

Treatment

Desmopressin acetate (DDAVP) administered nasally, orally, or by injection; affects prolonged antidiuretic activity and has no pressor effects, depending on dosage

Chlorpropamide (Diabinese): a sulfonylurea used in diabetes mellitus; also sometimes used to stimulate endogenous release of antidiuretic hormone and is effective if some pituitary function is intact

Carbamazepine to enhance the patient’s response to ADH; clofibrate to increase the release of ADH

Low-sodium, low-protein diet and thiazide diuretics to treat nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

Nursing considerations

Make sure that you keep accurate records of the patient’s hourly fluid intake and urine output, vital signs, and daily weight. Be sure to administer adequate replacement fluids.

Closely monitor the patient’s urine specific gravity. Also monitor serum electrolyte and blood urea nitrogen levels.

Watch the patient for signs of hypovolemic shock. Monitor blood pressure, pulse rate, and body weight. Also watch for changes in mental or neurologic status.

If the patient has any complaints of dizziness or muscle weakness, institute safety precautions to help prevent injury.

Make sure that the patient has easy access to the bathroom or bedpan. Insert an indwelling urinary catheter if the patient is incontinent so output can be monitored.

Provide meticulous skin and mouth care. Use a soft toothbrush and mild mouthwash to avoid trauma to the oral mucosa. If the patient has cracked or sore lips, apply petroleum jelly, as needed. Use alcohol-free skin care products, and apply emollient lotion to the patient’s skin after baths.

Use caution when administering vasopressin to a patient with coronary artery disease because the drug can cause coronary artery constriction. Therefore, closely monitor the patient’s electrocardiogram, looking for changes and exacerbation of angina.

Urge the patient to verbalize feelings. Offer encouragement, and provide a realistic assessment of the situation.

Help the patient identify his strengths, and help him see how he can use these strengths to develop effective coping strategies.

As necessary, refer the patient to a mental health professional for additional counseling.

Advise the patient to wear a medical identification bracelet at all times. Tell him he should always keep his medication with him.

Teaching about diabetes insipidus

Teaching about diabetes insipidus

Before the water restriction test, tell the patient to take nothing by mouth until the test is over, and explain the need for hourly urine tests, vital sign and weight checks and, if necessary, blood tests. Reassure the patient that he’ll be closely monitored.

Teach the patient and family about the disorder and treatment. Answer all questions as completely as possible.

Instruct the patient and family members to identify and report signs of severe dehydration and impending hypovolemia.

Tell the patient to record his weight daily, and teach him and family members how to monitor intake and output and how to use a hydrometer to measure urine specific gravity.

Encourage the patient to maintain fluid intake during the day to prevent severe dehydration but to limit fluids in the evening to prevent nocturia.

Inform the patient and family members about long-term hormone replacement therapy. Instruct the patient to take the medication as prescribed and to avoid abrupt discontinuation of the drug without the physician’s order. Teach them how to give subcutaneous or I.M. injections or how to use nasal applicators. Discuss the drug’s adverse effects and when to report them.

Teach the parents of a child with diabetes insipidus about normal growth and development; discuss how their child may differ. Encourage the parents to identify the child’s strengths and use them to develop coping strategies. Refer family members for counseling, if necessary.

Explain all testing and what patient participation is required.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease of absolute or relative insulin deficiency or resistance. It’s characterized by disturbances in carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism. Insulin deficiency compromises the body tissues’ ability to access essential nutrients for fuel and storage.

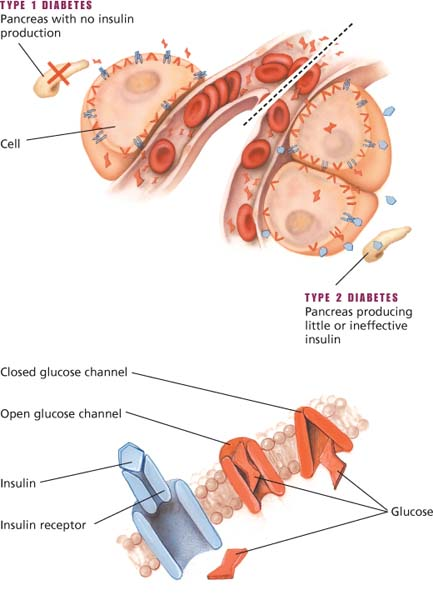

Diabetes mellitus occurs in two primary forms: type 1, characterized by absolute insufficiency; and the more prevalent type 2, characterized by insulin resistance with varying degrees of insulin secretory defects.

Onset of type 1 usually occurs before age 30, although it may occur at any age. type 2 usually occurs in obese adults after age 40; however, it’s becoming more common in North American youths.

Diabetes mellitus is thought to affect about 7% of the population of the United States (24 million people); about 6 million cases are undiagnosed. Incidence is essentially the same between males and females and increases with age.

In type 1 diabetes, pancreatic beta-cell destruction or primary defect in beta-cell function results in a failure to release insulin and ineffective glucose transport. Type 1 immune-mediated diabetes is caused by cell-mediated destruction of pancreatic beta cells. In type 2 diabetes, beta cells release insulin, but receptors resist insulin, glucose transport is variable and ineffective.

Signs and symptoms

Polyuria

Polydipsia

Polyphagia

Nausea and anorexia

Weight loss

Headaches, fatigue, lethargy, reduced energy levels, impaired school or work performance

Muscle cramps, irritability, emotional lability

Vision changes such as blurring

Numbness and tingling

Abdominal discomfort and pain; diarrhea or constipation

Recurrent infections

Delayed wound healing

Treatment

Type 1 diabetes

Exogenous insulin

Dietary management

Exercise therapy

Islet cell or pancreas transplantation

Type 2 diabetes

Insulin therapy

Oral antidiabetic drugs

Exercise therapy

Lipase inhibitor (such as orlistat) combined with a low-calorie diet to significantly decrease weight

Dietary management

Nursing considerations

Keep accurate records of vital signs, weight, fluid intake, urine output, and calorie intake. Monitor serum glucose and urine acetone levels.

Monitor for acute complications of diabetic therapy, especially hypoglycemia (vagueness, slow cerebration, dizziness, weakness, pallor, tachycardia, diaphoresis, seizures, and coma); immediately give carbohydrates in the form of fruit juice, hard candy, honey or, if the patient is unconscious, glucagon or I.V. dextrose. Also be alert for signs of hyperosmolar coma (polyuria, thirst, neurologic abnormalities, and stupor). This hyperglycemic crisis requires I.V. fluids and insulin replacement.

Monitor diabetic effects on the cardiovascular system, such as cerebrovascular, coronary artery, and peripheral vascular impairment, and on the peripheral and autonomic nervous systems.

Provide meticulous skin care, especially to the feet and legs. Treat all injuries, cuts, and blisters. Avoid constricting clothing, slippers, or bed linens. Refer the patient to a podiatrist if indicated.

Observe for signs of urinary tract and vaginal infections. Encourage adequate fluid intake.

Monitor the patient for signs of diabetic neuropathy (numbness or pain in the hands and feet, footdrop, and neurogenic bladder).

Consult a dietitian to plan a diet with the recommended allowances of calories, protein, carbohydrates, and fats, based on the patient’s particular requirements.

Encourage the patient to verbalize feelings about diabetes and its effects on lifestyle and life expectancy. Offer emotional support and a realistic assessment of his condition. Stress that with proper treatment, he can lead a relatively normal life. Help the patient to develop coping strategies. Refer him and his family for counseling, if necessary. Encourage them to join a support group.

Teaching about diabetes mellitus

Teaching about diabetes mellitus

Stress the importance of carefully adhering to the prescribed program and blood glucose control. Tailor your teaching to the patient’s needs, abilities, and developmental stage. Discuss diet, medications, exercise, monitoring techniques, hygiene, and how to prevent and recognize hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia.

To encourage compliance to lifestyle changes, emphasize how blood glucose control affects long-term health. Teach the patient how to care for his feet: He should wash them daily, carefully dry between his toes, and inspect for corns, calluses, redness, swelling, bruises, and breaks in the skin. Urge him to report any skin changes to the physician. Advise him to wear comfortable, nonconstricting shoes and never to walk barefoot.

Urge annual regular ophthalmologic examinations for early detection of diabetic retinopathy.

Describe the signs and symptoms of diabetic neuropathy and emphasize the need for safety precautions because decreased sensation can mask injuries.

Teach the patient how to manage diabetes when he has a minor illness, such as a cold, flu, or upset stomach.

To prevent diabetes, teach people at high risk to maintain proper weight and exercise regularly. Advise genetic counseling for adult diabetic patients who are planning families.

Teach the patient and his family how to monitor the patient’s diet. Teach how to read labels in the supermarket to identify fat, carbohydrate, protein, and sugar content.

Encourage the patient and his family to contact the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the American Diabetes Association to obtain additional information.

Hyperthyroidism

Thyroid hormone overproduction results in the metabolic imbalance hyperthyroidism, which is also called thyrotoxicosis.

The most common form is Graves’ disease, which increases thyroxine (T4) production, enlarges the thyroid gland (goiter), and causes multiple systemic changes. Incidence of Graves’ disease is highest between ages 30 and 40, especially in people with family histories of thyroid abnormalities; only 5% of hyperthyroid patients are younger than age 15. With treatment, most patients can lead normal lives.

However, thyrotoxic crisis (or thyroid storm), an acute exacerbation of hyperthyroidism, is a medical emergency that can lead to life-threatening cardiac, hepatic, or renal failure.

Signs and symptoms

Enlarged thyroid

Nervousness

Heat intolerance

Weight loss despite increased appetite

Sweating

Frequent bowel movements

Tremor

Palpitations

Exophthalmos (considered most characteristic but is absent in many patients with thyrotoxicosis)

Understanding thyrotoxic crisis

Thyrotoxic crisis—also known as thyroid storm—is an acute manifestation of hyperthyroidism. It usually occurs in patients with preexisting (though often unrecognized) thyrotoxicosis. Left untreated, it’s invariably fatal.

Pathophysiology

The thyroid gland secretes the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine and thyroxine. When it overproduces them in response to any of the precipitating factors listed at right, systemic adrenergic activity increases. This results in epinephrine overproduction and severe hypermetabolism, leading rapidly to cardiac, GI, and sympathetic nervous system decompensation.

Assessment findings

Initially, the patient may have marked tachycardia, vomiting, and stupor. If left untreated, he may experience vascular collapse, hypotension, coma, and death. Other findings may include a combination of agitation and psychosis progressing to lethargy and coma; visual disturbance such as diplopia; tremor and weakness; heart failure, pulmonary edema; and swollen extremities. Palpation may disclose warm, moist flushed skin and a high fever (beginning insidiously and rising rapidly to a lethal level).

Precipitating factors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Manifestations of Cushing’s syndrome

Manifestations of Cushing’s syndrome

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus

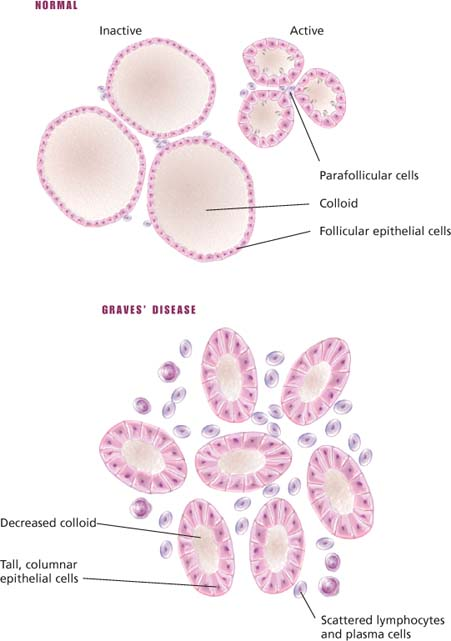

Histologic changes in Graves’ disease

Histologic changes in Graves’ disease