E

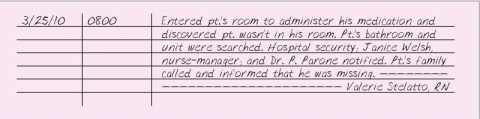

ELOPEMENT FROM A HEALTH CARE FACILITY

If you discover that a patient is missing or has left the health care facility without having said anything about leaving (called “elopement”), look for him on your unit immediately and notify the nurse-manager, the patient’s physician, and his family. Notify the police if the patient is at risk for harming himself or others.

The legal consequences of a patient leaving the facility without medical permission can be particularly severe, especially if he’s confused, mentally incompetent, or injured or if he dies of exposure as a result of his absence.

EMERGENCY TREATMENT, PATIENT REFUSAL OF

A competent adult has the right to refuse emergency treatment. His family can’t overrule his decision, and his doctor isn’t allowed to give the expressly refused treatment, even if the patient becomes unconscious.

In most cases, the health care personnel who are responsible for the patient can remain free from legal jeopardy as long as they fully inform the patient about his medical condition and the likely consequences of refusing treatment. The courts recognize a competent adult’s right to refuse medical treatment, even when that refusal will clearly result in his death. If the patient understands the risks but still refuses treatment, notify the nursing supervisor and the patient’s doctor.

The courts recognize several circumstances that justify overruling a patient’s refusal of treatment. These include instances when refusing treatment endangers the life of another, when a parent’s decision threatens the child’s life, or when, despite refusing treatment, the patient makes statements to indicate he wants to live. If none of these grounds exist, then you have an ethical duty to defend your patient’s right to refuse treatment. Try to explain the patient’s choice to his family. Emphasize that the decision is his as long as he’s competent.

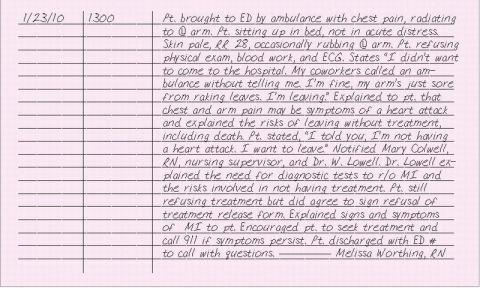

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

When your patient refuses care, document that you have explained the care and the risks involved in not receiving it. Document your patient’s understanding of the risks, using his own words. Record the names of the nursing supervisor and doctor you notified and the time of notification. Document that the doctor saw the patient and explained the risks of refusing emergency treatment.

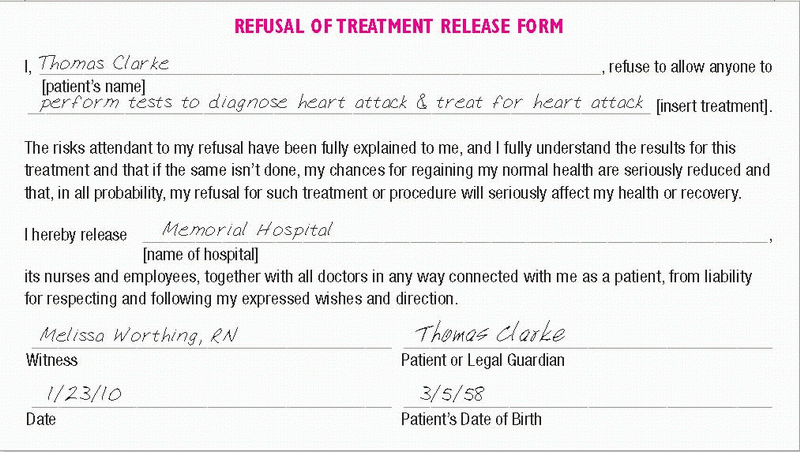

Ask the patient to complete a refusal of treatment form. (See Refusal of treatment form.) The signed form indicates that appropriate treatment would have been given had the patient consented. If the patient refuses to sign the release form, document this in your nurse’s note by writing “refused to sign” on the patient’s signature line. Initial it with your own initials and date it. For additional protection, your facility may require you to get the patient’s spouse or closest relative to sign a refusal of treatment form. In the same manner as you did for the patient, document whether the spouse or relative does this.

|

END-OF-LIFE CARE

Nurses must meet the physical and emotional end-of-life needs of both the dying patient and his family. The dying patient may experience a variety of physical symptoms, including pain, respiratory distress, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, and bowel problems. Emotional concerns may include confusion, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and spiritual distress. Your nursing interventions should be individualized to the specific needs of the patient.

The nurse can also make the death more comfortable and meaningful for the family. Tell the family what to expect, if they want to hear about it. Encourage them to talk to and touch the patient. Allow them to help with care, if they desire. Provide them with a comfortable environment, encourage verbalization of concerns and feelings, and determine whether they would like a member of the clergy to visit.

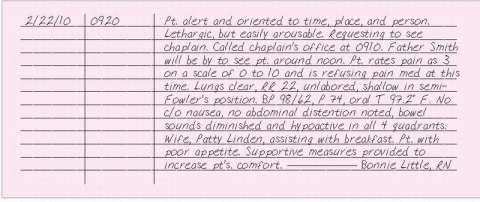

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the time and date of your entry. Document your interventions related to pain assessment and management, relief of respiratory distress, administration or withholding of nutrition and hydration, control of nausea and vomiting, and management of bowel problems. Describe measures taken to meet the patient’s emotional needs and his response. If you call the doctor, include the time and date of notification, orders given, and whether the doctor saw the patient. Include the names of other people or departments you notified (such as pastoral care, respiratory therapy, or nutritional support), the time you called, the reason for your telephone call, and the response.

Also, record your interventions to meet the physical and emotional needs of the family, the names of family members present, and their responses. Document any teaching you provided the patient and his family and their responses to teaching. In some facilities, teaching may be documented on a patient-teaching record.

|

ENDOTRACHEAL EXTUBATION

When your patient no longer requires endotracheal (ET) intubation, the airway can be removed. Explain the procedure to your patient and obtain another nurse’s assistance to prevent traumatic manipulation of the tube when it’s untaped or unfastened. Teach the patient to cough and deepbreathe after the ET tube is removed, and assess him frequently for signs of respiratory distress.

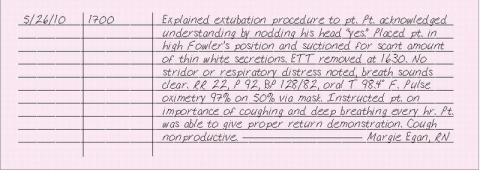

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of extubation, presence or absence of stridor or other signs of upper airway edema, breath sounds, type and amount of supplemental oxygen administered, any complications and required subsequent therapy, and the patient’s tolerance of the procedure. Document patient teaching and support given.

|

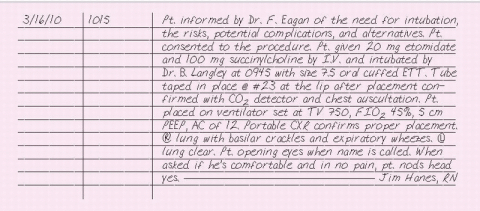

ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION

Endotracheal (ET) intubation involves the oral or nasal insertion of a flexible tube through the larynx into the trachea for the purpose of controlling the airway and mechanically ventilating the patient. Performed by a doctor, anesthetist, respiratory therapist, or nurse educated in the procedure, ET intubation usually occurs in emergencies such as cardiopulmonary arrest, or in diseases such as epiglottiditis. However, ET intubation may also occur under more controlled circumstances; for example, just before surgery. In these instances, ET intubation requires teaching and preparing the patient.

ET intubation establishes and maintains a patent airway, protects against aspiration by sealing off the trachea from the digestive tract, permits removal of tracheobronchial secretions in patients who can’t cough effectively, and provides a route for mechanical ventilation.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Document that the doctor explained the procedure, risks, complications, and alternatives to the patient or person responsible for making decisions concerning the patient’s health care. Indicate that the patient or health care proxy consented to the procedure. Record the date and time of intubation and the name of the person performing the procedure. Include indications for the procedure and success or failure. Chart the type and size of tube, cuff size, amount of inflation, and inflation technique. Indicate whether drugs were administered. Document the initiation of supplemental oxygen or ventilation therapy. Record the results of chest auscultation and chest X-ray. Note the occurrence of any complications, necessary interventions, and the patient’s response. Describe the patient’s reaction to the procedure. Also, document any teaching done before and after the procedure.

|

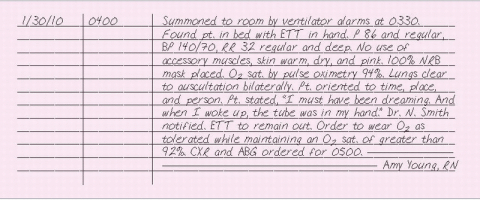

ENDOTRACHEAL TUBE, PATIENT REMOVAL OF

Because an endotracheal (ET) tube is used to provide mechanical ventilation and maintain a patent airway, the removal of an ET tube by a patient may be an emergency situation. The patient may not have spontaneous respirations, may be in severe respiratory distress, or may suffer trauma to the larynx or vocal cords.

If your patient removes his ET tube, stay with him and call for help. Assign someone to notify the doctor while you assess the patient’s respiratory status. If the patient is in distress, perform manual ventilation while others prepare for reinsertion of the ET tube and monitor vital signs. If your patient is alert, speak calmly and explain the reintubation procedure. If the patient isn’t in distress, provide oxygen therapy. If the decision is made not to reintubate the patient, monitor his respiratory status and vital signs every 15 minutes for 2 to 3 hours, or as ordered by the doctor. Some facilities also require that an incident report be completed.

ESSENTIAL DOCUMENTATION

Record the date and time of your entry. Note how you discovered the ET tube was removed by the patient. Record your respiratory assessment. Record the name of the doctor notified and the time of notification. Document your actions, such as oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation, and the patient’s response. If the patient required reinsertion of the ET tube, follow the procedure for documenting endotracheal intubation. (See “Endotracheal intubation.”) Record any patient education provided.

|

END-TIDAL CARBON DIOXIDE MONITORING

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

REFUSAL OF TREATMENT FORM

REFUSAL OF TREATMENT FORM